Community Education in British Urban Priority Areas with Special Reference to Hull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not for Publication by Virtue of Paragraph 1 of Part 1 Of

Children’s Services Overview and Scrutiny Commission Panel Enquiry into Youth Services June, 2008 Scrutiny Report No # Chair’s Foreword This enquiry was undertaken after members of the former Lifelong Learning, Culture and Leisure Overview and Scrutiny Commission expressed concern regarding the impact the Youth Matters Green Paper would have on the provision of existing youth provision in the City. In particular we felt that historically, the move to a curriculum based youth service had led to a significant drop in the number of young people accessing youth services in the City. We realised that there were a significant number of current and emerging issues at a national level which would impact on the future delivery of youth services, across all sectors, at a local level. For these reasons we have made a number of strategic recommendations which should be taken into consideration as part of any future service reconfiguration and future commissioning of services for young people. During the course of the enquiry we established that there were a number of areas within the spectrum of both statutory and voluntary youth services which should be addressed. In particular, we found that a number of issues relating to the way the City Council worked with community and voluntary sector organisations in delivering quality, value for money youth activities within the City. We also recognised the need to redress the balance between universal and targeted youth work plus the urgent need to reintroduce outreach and detached youth work within the City. The Panel received a lot of evidence and considered the options very carefully, placing the views of young people as a priority. -

INTERNAL POST Members Information INTERNAL POST

HUMBER BRIDGE Councillor L Redfern Councillor D Gemmell BOARD North Lincolnshire Council, Civic Kingston upon Hull City Council Centre Ashby Road Scunthorpe DN16 1AN Councillor S Parnaby OBE, Councillor C Shaw Lord C Haskins East Riding of Yorkshire Council North East Lincolnshire Council Quarryside Farm, County Hall Skidby, Beverley Cottingham, HU17 9BA East Yorkshire, HU16 5TG Mr S Martin Professor D Stephenson Mr J Butler Chief Executive, Clugston Clerk to the Humber Bridge 33 Hambling Drive Group Ltd Board Molescroft St Vincent House, Normanby Beverley Road, Scunthorpe HU17 9GD DN15 8QT Mr P Hill Mr P Dearing Anita Eckersley General Manager and Legal Services Committee Clerk to the Humber Bridgemaster Kingston upon Hull City Council Bridge Board Humber Bridge Administration Offices Ferriby Road, Hessle HU13 0JG Councillor Turner MBE, Other recipients for Mrs J Rae, Audit Commission Lincolnshire County Council information, Audit Commission c/o Hull City Council, Floor 2 Wilson Centre, Alfred Gelder Street, Hull HU1 2AG Nigel Pearson Simon Driver Shaun Walsh, Chief Executive Chief Executive Chief Executive East riding of Yorkshire Council North Lincolnshire Council North East Lincolnshire Council Civic Centre, Ashby Road Municipal Offices, Town Hall Scunthorpe Square, Grimsby DN16 1AN DN31 1HU INTERNAL POST INTERNAL POST Members Information Reference Library APPEALS COMMITTEE Councillor Abbott Councillor Conner Councillor P D Clark INTERNAL MAIL INTERNAL MAIL G Paddock K Bowen Neighbourhood Nuisance Team Neighbourhood Nuisance Team HAND -

Hull Core Strategy Volume 3: Report on Engagement

Hull Core Strategy Volume 3: Report on engagement June 2011 Volume 3 – Report on engagement on the Hull Core Strategy Introduction This report details further community engagement used to inform the Publication version of the Core Strategy. It includes comments: • made over the period from June 2008 in response to the Core Strategy – Issues/options stage; and • up to and after the February 2010 Core Strategy – Emerging Preferred Approach (up to March 2010). Details are provided in terms of the responses made through the City Council, as detailed in Appendix 1 and through meetings with other stakeholders outside of the City Council, as detailed in Appendix 2. Appendix 3 outlines comments on the accompanying Sustainability Appraisal. This volume forms an additional part of ‘front loading’ the engagement process in conforming with the Council’s adopted Statement of Community Involvement and under Regulation 25 of the Town and Country Planning Local Development Regulations, 2008. It should be read alongside other community engagement work as detailed in Volumes 1 and 2. Background The City Council has completed extensive engagement in preparing its Hull Core Strategy, in meeting soundness tests and localism objectives. It has completed these tasks in conforming to its Statement of Community Involvement, adopted 2006. Feedback from various plan making stages has informed the preparation of policies in tackling social, economic and environmental challenges facing the future city. In summary, community involvement in plan preparation has included -

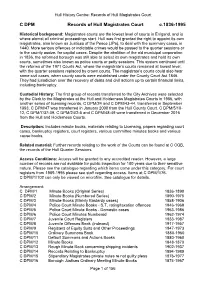

C DPM Records of Hull Magistrates Court C.1836-1995

Hull History Centre: Records of Hull Magistrates Court C DPM Records of Hull Magistrates Court c.1836-1995 Historical background: Magistrates courts are the lowest level of courts in Enlgand, and is where alomst all criminal proceedings start. Hull was first granted the right to appoint its own magistrates, also known as Justices of the Peace (JPs), to deal with the summary cases, in 1440. More serious offences or indictable crimes would be passed to the quarter sessions or to the county assize, for capital cases. Despite the abolition of the old municipal corporation in 1836, the reformed borough was still able to select its own magistrates and hold its own courts, sometimes also known as police courts or petty sessions. This system continued until the reforms of the 1971 Courts Act, where the magistrate’s courts remained at lowest level, with the quarter sessions replaced by crown courts. The magistrate’s courts could also hear some civil cases, when county courts were established under the County Court Act 1846. They had jurisdiction over the recovery of debts and civil actions up to certain financial limits, including bankruptcy. Custodial History: The first group of records transferred to the City Archives were selected by the Clerk to the Magistrates at the Hull and Holderness Magistrates Courts in 1986, with another series of licensing records, C DPM/24 and C DPM/43-44, transferred in September 1993. C DPM/47 was transferred in January 2008 from the Hull County Court. C DPM/5/10- 12, C DPM/7/37-39, C DPM/24/2-5 and C DPM/48-49 were transferred in December 2016 from the Hull and Holderness Courts. -

Strategic Economic Plan 2014-2020

Strategic Economic Plan Strategic Economic Plan 2014-2020 Strategic Economic Plan Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Ambition ................................................................................................................................................ 10 3. The Humber in context ......................................................................................................................... 17 4. The potential of the Energy Estuary .................................................................................................... 42 5. Sectors of strategic importance .......................................................................................................... 46 6. Creating an infrastructure that supports growth................................................................................ 63 7. Supporting businesses to succeed ..................................................................................................... 70 8. A great place to live and visit ............................................................................................................. -

Conservative and Unionist Group Response

2017 Kingston-Upon-Hull Local Government Boundary Review Conservative and Unionist Group Response Conservative and Unionist Group Submission March 2017 INTRODUCTION The Conservative Group welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Local Government Boundary Commission’s (LGBCE hereafter) proposals. We may also spend some time commenting on other proposals put forward by other political groups, but feel the main thrust of our remarks on the consultation should be around the LGBCE proposals. Our commentary, like our initial proposals, is based around adherence to the three main tenets of the LGBCE as highlighted on their website:- “The aim of the electoral review is to recommend ward boundaries that mean each councillor represents approximately the same number of voters. We also aim to ensure that the pattern of wards reflects the interests and identities of local communities as well as promoting effective local government.”1 To further highlight the key criteria for drawing up wards which we will refer back to throughout this submission document, they are to: 1 ensure each councillor represents approximately the same number of voters 2 ensure that the pattern of wards reflects the interests and identities of local communities 3 promote effective local government We have also adhered, as far as possible, to our belief that railway lines and dual carriageways are major constraints on identifying a community. Traditionally, canals and rivers are also seen as natural barriers and we feel we need to turn a little to the subject of the river – a topic that greatly exercises the minds of Hullensians. In cities such as York, Dublin, Belfast, and London the rivers are substantial and although the Ouse and Thames are crossed frequently by major bridges it is still a considerable barrier to traverse. -

Ull History Centre: U DPW

Hull History Centre: U DPW U DPW Records of Patrick Wall MP 1890-1992 Accession number: 1993/25 Historical Background/Biographical Background: Patrick Henry Bligh Wall was born in Cheshire on 19 October 1916, the son of Henry Benedict Wall and Gladys Eleanor Finney. He was educated at Downside School, Bath. In 1935 he was commissioned in the Royal Marines, training to become a specialist in naval gunnery. During the Second World War, he served on various Royal Navy vessels, including Iron Duke, Valiant and Malaya, between 1940 and 1943. From 1943 to 1945 he served in RN support craft, with the United States Navy and then with the Royal Marine Commandos. He was awarded both the Military Cross and the US Legion of Merit in 1945. After the war he studied at the Royal Naval Staff College and the Joint Services Staff College, and was a staff instructor at the School of Combined Operations between 1946 and 1948. His last appointment afloat was in HMS Vanguard in 1949. He retired as a Major in 1950 in order to concentrate on a political career. However he remained a Reservist, commanding 47 Commando, Royal Marine Forces Volunteer Reserve, from 1951 until its disbandment in 1956. He was awarded the Volunteer Reserve Decoration (VRD) in 1957. His involvement in naval affairs was continued for many years through his work with the City of Westminster Sea Scout and Sea Cadet organisations, and the London Sea Scout Committee. He contested the Cleveland constituency for the Conservative Party in the general election of 1951, and again at a bye-election the following year. -

"Providing Long Term Sustainable Management of Flood Risk"

River Hull Advisory Board River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy May 2016 Strategy Document Final report "Providing long term sustainable management of flood risk" This document was issued and approved as follows: Version Control Version Originator Checked Date Comment 1 BK AM 10/07/2015 2 CB AM 30/03/2016 3 BK AM 31/05/2016 Partner Approvals Record Organisation Approver Date of Approval East Riding of Yorkshire Council Cabinet 7 July 2015 Hull City Council Cabinet 22 June 2015 Area Flood and Coastal Environment Agency 3 July 2015 Risk Manager Beverley & North Holderness Board 8 July 2015 Internal Drainage Board Yorkshire Water Flood Risk Manager 9 July 2015 River Hull Advisory Board Board 10 July 2015 Through the above approval the partners are recognising the work that has been carried out to produce the River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy which sets out a holistic and strategic approach to managing the flood risk for the River Hull catchment. The partners have agreed to have regard to this Strategy in formulating their future proposals for managing flood risk within the catchment. The progression of individual projects or interventions identified within this Strategy will be subject to the normal assurance and approval processes of the individual body concerned and those of any relevant funding body. i RIVER HULL ADVISORY BOARD RIVER HULL INTEGRATED CATCHMENT STRATEGY MAY 2016 ©2016. East Riding of Yorkshire Council. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of East Riding of Yorkshire Council ii Contact information For further information about this Strategy, please contact us using the details below. -

Overview & Scrutiny Action List 2013-2014

OVERVIEW & SCRUTINY ACTION LIST 2013-2014 Energy and Infrastructure Overview and Scrutiny Commission SCRUTINY CHAIR: LEAD OFFICER: Andy Burton OFFICER: Councillor (Trish Dalby) / Mark Jones Fiona DEMOCRATIC SERVICES OFFICER: Michelle Rowbottom Allen (Pauline Davis) Harbord Responsible Commission Reason for submission and actions (the reason for submission DUE Agenda Items Officer (In Outcome/Update Info RAG Date should be specified in the level 1 cell, action in level 2 cells) DATE attendance) Council instructs the officers, consulting with rail and bus operators where appropriate, to prepare a paper for the The Passenger Experience in Andy Burton 04/06/2013 Environment and Transport Overview and Scrutiny Commission Hull's Transport Interchange (Graham Hall) on how the passenger experience in the Hull Interchange can be improved along these lines. Current contract with FTPE due to end in 18 months (end That the Commission wishes to be consulted on the provision of of 2014). Item will be included in the 2014/15 work Customer Information within the Transport Interchange, when the programme in advance of that date so that Member may Jul-14 A current contract comes to an end to enable consideration to be given discusss and decide changes that they would like to to changing the layout of the information displays recommend To update the Commission on current/key issues and for City Manager Presentation - members to identify matters to be considered, and raise 01/10/2013 Mark Jones Greenport update (15 mins) questions and issues on the presentation, that may lead to further work being undertaken. That the City Economic Development and Regeneration Manager will attend a meeting of the Energy and Infrastructure Overview and 2014/15 A Scrutiny Commission when the final investment decision from Siemens is received Mark Jones To inform the Commission of the planned development of District (Martin Budd 01/10/2013 District Heating Heating Schemes in Hull, including the specific scheme on / Mark Leaf / Orchard Park Estate. -

Advice and Information

Contents Contents Advice & Information Organisations and initiatives that you can contact Pages 1 – 5 for advice and information Education Mainstream and special educational needs Pages 6 – 11 services Having a Break Information on short-break and respite services Pages 12 – 13 Family Support Support agencies and groups available for families Pages 14 – 22 Health Health service provision for children and young Pages 23 – 28 people National Organisations Useful Information on national organisations Pages 29 – 37 Contents Contents Mobility & Travel Services and schemes available to help with Pages 38 – 39 mobility and travel Holidays Holidays for disabled people Pages 40 – 41 Play & Leisure Play and leisure services and activities in Hull Pages 42 – 47 Money Matters This section covers the benefits available Page 48 Childrens Centres Contact details of the Children’s Centres in Pages 49 – 51 Hull Comments, This section gives details of where to make Compliments your comments, compliments and complaints & Complaints Page 52 Advice &Information Advice and Information Addvis @ Addvis -Providing goods and services relating to the needs of people with a HERIB visual impairment. This includes sourcing aids and equipment suited to Beech Holme, individual needs, Guide Talking software and a full transcription service. Beverley Road Hull HU5 1NF HERIB offers an Eye Clinic Support Service HERIB has an IT resource Tel: 01482 342297 centre which is open to the public, at a small cost ,that enables people with Email: [email protected] visual impairments and physical disabilities to access literature and the internet. The resource centre is open Monday to Friday 0900 to 1700. Career Choices As part of Hull City Council Training, the Career Choices Centre provides 26 Raywell Street support and development through the provision of learning resources to a Hull, HU2 8EP variety of young people within Hull and East Yorkshire. -

11934 HULL 1 Tel: 01482 300300

Please ask for: Nikki Stocks Telephone: 01482 613421 Fax: 01482 613110 Email: [email protected] Text phone: 01482 300349 Date: Wednesday, 25 February 2015 Dear Councillor, Northern Area Committee The next meeting of the Northern Area Committee will be held at 18:00 on Thursday, 05 March 2015 in The Orchard Centre, Orchard Park Road, Hull, HU6 9BX. The Agenda for the meeting is attached and reports are enclosed where relevant. Please Note: It is likely that the public, (including the Press) will be excluded from the meeting during discussions of exempt items since they involve the possible disclosure of exempt information as describe in Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. Yours faithfully, Democratic Services Officer for the Chief Executive Town Clerk Services, Hull City Council, The Guildhall, AlfredPage Gelder 1 of 72 Street, Hull, HU1 2AA www.hullcc.gov.uk DX: 11934 HULL 1 Tel: 01482 300300 Northern Area Committee To: Membership: Councillors S Bayes, J Conner, T Geraghty, J Korczak Fields, K Mathieson, D McCobb and S Wilson. Officers: Jane Price, Assistant City Manager (Neighbourhoods) Ken Upshall, Community Manager for Northern & North Carr Nikki Stocks, Democratic Services Officer (x5) Public Set: Reference Library Alerts: Councillor J Hewitt, Portfolio Holder for Customer and Neighbourhood Services Chief Executives Office, Kingston upon Hull City Council Councillor A Bell, Leader of the Majority Opposition Guildhall Reception Press Office Group Secretariats Tom Clay, Political Assistant [email protected] Viking Radio – [email protected] Yorkshire Post – [email protected] & [email protected] & [email protected] Radio Humberside – [email protected] Hull Daily Mail – [email protected] & [email protected] KCFM Radio – [email protected] Page 2 of 72 Northern Area Committee 18:00 on Thursday, 05 March 2015 The Orchard Centre, Orchard Park Road, Hull, HU6 9BX A G E N D A PROCEDURAL ITEMS 1 Apologies To receive apologies for those Members who are unable to attend the meeting. -

North Area Committee

Please ask for: Nicola Stocks Telephone: 01482 613421 Fax: 01482 614804 Email: [email protected] Text phone: 01482 300349 Date: Tuesday, 19 January 2021 Dear Councillor, North Area Committee The next meeting of the North Area Committee will be held at 18:00 on Thursday, 28 January 2021 in Council Chamber . The Agenda for the meeting is attached and reports are enclosed where relevant. Please Note: It is likely that the public, (including the Press) will be excluded from the meeting during discussions of exempt items since they involve the possible disclosure of exempt information as describe in Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. Yours faithfully, Democratic Services Officer for the Town Clerk Town Clerk Services, Hull City Council, The Guildhall, Alfred Gelder Street, Hull, HU1 2AA www.hullcc.gov.uk Tel: 01482 300300 Page 1 of 112 North Area Committee To: Membership: Councillors Drake-Davis, Lunn, Matthews, McCobb, Nicola (DC), Ross, Wareing (C), Wilson Officers: Alistair Shaw, Community Manager (Neighbourhoods) Mark McEgan, Assistant City Manager (Housing Management) Nicola Stocks, Democratic Services Officer (x5) Public Set: Reference Library Please note that due to the current public health situation in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak and in accordance with the Coronavirus Act (2020) s. 78 and the subsequent Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations (2020) this meeting will be available to view online here: http://www.hullcc.nucast.live/ Elected Members, Officers and members of the public, where they wish to make representations, who will be attending this meeting remotely will be provided with joining instructions separately.