Gendered Crisis Reporting: a Content Analysis of Crisis Coverage on ABC, CBS, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Murder, She Wrote' and 'Perry Mason" (K:-En E

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 087 CS 509 181 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (78th, Washington, DC, August 9-12, 1995). Qualitative Studies Division. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE Aug 95 NOTE 404p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 509 173-187 and CS 509 196. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indians; *Ethics; Higher Education; *Journalism; Journalism History; Labor Standards; Lying; Media Research; *Online Systems; Periodicals; Political Issues; Qualitative Research; *Racial Attitudes; Research Methodology; *Television Viewing IDENTIFIERS Gulf War; Jdia Coverage; Media Government Relationship; Simpson (0 J) Murder Trial ABSTRACT The Qualitative Studies section of the proceedings contains the following 14 papers: "'Virtual Anonymity': Online Accountability in Political Bulletin Boards and the Makings of the Virtuous Virtual Journalist" (Jane B. Singer); "The Case of the Mysterious Ritual: 'Murder, She Wrote' and 'Perry Mason" (K:-en E. Riggs); "Political Issues in the Early Black Press: Applying Frame Analysis to Historical Contexts" (Aleen J. Ratzlaff and Sharon Hartin Iorio); "Leaks in the Pool: The Press at the Gulf War Battle of Khafji" (David H. Mould); "Professional Clock-Punchers: Journalists and the Overtime Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act"(Robert Jensen); "Love, Gender and Television News" (Don Heider and Leona Hood); "Tabloids, Lawyers and Competition Made Us Do It!: How Journalists Construct, Interpret and Justify Coverage of the O.J. Simpson Story" (Elizabeth K. Hansen); "The Taming of the Shrew: Women's Magazines and the Regulation of Desire" (Gigi Durham); "Communitarian Journalism(s): Clearing the Conceptual Landscape" (David A. -

The Role of Appearance in the Careers of Hispanic Female Broadcasters Rachel E

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2017 Beauty in the Eye of the Producer: The Role of Appearance in the Careers of Hispanic Female Broadcasters Rachel E. Anderson University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Rachel E., "Beauty in the Eye of the Producer: The Role of Appearance in the Careers of Hispanic Female Broadcasters" (2017). Honors Theses. 768. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/768 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEAUTY IN THE EYE OF THE PRODUCER: THE ROLE OF APPEARANCE IN THE CAREERS OF HISPANIC FEMALE BROADCASTERS BY RACHEL E. ANDERSON A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College University, Mississippi May 2017 Approved by ________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Kathleen W. Wickham ________________________________ Reader: Dr. Diane E. Marting ________________________________ Reader: Mr. Charles D. Mitchell, JD © 2017 Rachel E. Anderson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This paper explores the pressures of beauty and appearance on a selected group of female Hispanic broadcast journalists. Ten broadcasters who identify as female and Hispanic were interviewed about their experiences in the industry. A careful analysis indicated that there are pressures for adopting ultra-feminine looks for hair and makeup and sexy clothing for on-air appearances based on consumer feedback. -

FALLACIES by John Chancellor BERT R

DIRECTING MET: Kirk Browning FIRST AMENDMENT FREEDOMS: Bob Packwood THE DOCUDRAMA DILEMMA: Douglas Brode GRENADA AND THE MEDIA: John Chancellor IN AWORLD OF SUBTLETY, NUANCE, AND HIDDEN MEANING... "Wo _..,". - Ncyw4.7 T-....: ... ISN'T IT GOOD TO KNOW THERE'S SOMETHING THAT CAN EXPRESS EVE MOOD. The most evocative scenes in recent movies simply wouldn't ha tive without the film medium. The artistic versatility of Eastman color negative films lish any kind of mood or feeling, without losing believability. x Film is also the most flexible post -production medium. When yá ,;final negative imagery to videotape or to film, you can expect exception ds and feelings on Eastman color films, the best medium for your 'magi ó" Eastman film. It's looking Eastman Kodak Company, 1982 we think international TV Asahi Asahi National Broadcasting Co., Ltd. Celebrating a Decade of Innovation THE JOURNAL OF THE VOLUME XX NUMBER IV 1984 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES S'} TELEVI e \ QUATELY CONTENTS EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR 7 VIDEO VERITÉ: DEFINING THE RICHARD M. PACK DOCUDRAMA by Douglas Brode CHAIRMAN HERMAN LAND 27 THE MEDIA AND THE INVASION MEMBERS OF GRENADA: FACTS AND ROYAL E. BLAKEMAN FALLACIES by John Chancellor BERT R. BRILLER JOHN CANNON 39 THERE WAS "AFTER" JOHN GARDEN BEFORE SCHUYLER CHAPIN THERE WAS ... by John O'Toole MELVIN A. GOLDBERG FREDERICK A. JACOBI 51 PROTECTING FIRST AMENDMENT ELLIN IvI00RE IN THE AGE OF THE MARLENE SANDERS FREEDOMS ALEX TOOGOOD ELECTRONIC REVOLUTION by Senator Bob Packwood 61 THE "CRANIOLOGY" OF THE 20th CENTURY: RESEARCH ON TELEVISION'S EFFECTS by Jib Fowles 75 CALLING THE SHOTS AT THE GRAPHICS DIRECTOR METROPOLITAN OPERA ROBERT MANSFIELD Kirk Browning -interviewed by Jack Kuney 93 REVIEW AND COMMENT: Three views of the MacNeil/Lehrer S. -

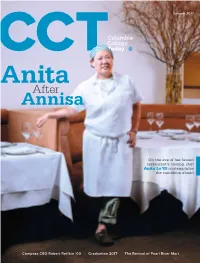

Ccttoday Anita After Annisa

Summer 2017 Columbia College CCTToday Anita After Annisa On the eve of her famed restaurant’s closing, chef Anita Lo ’88 contemplates the transition ahead Compass CEO Robert Reffkin ’00 | Graduation 2017 | The Revival of Pearl River Mart “Every day, I learned something that forced me to reevaluate — my opinions, my actions, my intentions. The potential for personal growth is far greater, it would seem to me, the less comfortable you are.” — Elise Gout CC’19, 2016 Presidential Global Fellow, Jordan Program Our education is rooted in the real world — in internships, global experiences, laboratory work and explorations right here in our own great city. Help us provide students with opportunities to transform academic pursuits into life experiences. Support Extraordinary Students college.columbia.edu/campaign Contents features 14 After Annisa On the eve of her famed restaurant’s closing, chef Anita Lo ’88 contemplates the transition ahead. By Klancy Miller ’96 20 “ The Journey Was the Exciting Part” Compass CEO Robert Reffkin ’00, BUS’03 on creating his own path to success. By Jacqueline Raposo 24 Graduation 2017 The Class of 2017’s big day in words and photos; plus Real Life 101 from humor writer Susanna Wolff ’10. Cover: Photograph by Jörg Meyer Contents departments alumninews 3 Within the Family 38 Lions Telling new CCT stories online. Joanne Kwong ’97, Ron Padgett ’64 By Alexis Boncy SOA’11 41 Alumni in the News 4 Letters to the Editor 42 Bookshelf 6 Message from Dean James J. Valentini High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist The Class of 2017 is a “Perfect 10.” and the Making of an American Classic by Glenn Frankel ’71 7 Around the Quads New Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition at MOMA 44 Reunion 2017 organized by Barry Bergdoll ’77, GSAS’86. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2005 - JUNE 30, 2006 www.cfr.org New York Headquarters 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Phone: 212-434-9400 Fax: 212-434-9800 Washington Office 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 Phone: 202-518-3400 Fax: 202-986-2984 Email: [email protected] Officers and Directors, 2006-2007 Officers Directors Officers and Directors, Emeritus and Honorary Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2007 Chairman Fouad Ajami Leslie H. Gelb Carla A. Hills* Kenneth M. Duberstein President Emeritus Wee Chairman Ronald L. Olson Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Peter G. Peterson*! Vice Chairman Thomas R. Pickering Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Richard N. Haass Laura D'Andrea Tyson Director Emeritus President David Rockefeller Term Expiring 2008 Janice L. Murray Honorary Chairman Martin S. Feldstein Sen/or Vice President, Treasurer, Robert A. Scalapino and Chief Operating Officer Helene D. Gayle Director Emeritus David Kellogg Karen Elliott House Sen/or Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Michael H. Moskow and Publisher Richard E. Salomon Nancy D. Bodurtha Anne-Marie Slaughter ^*^ Vice President, Meetings BC Term Expiring 2009 Irina A. Faskianos Wee President, National Program Madeleine K. Albright and Outreach Richard N. Foster Suzanne E. Helm Maurice R. Greenberg vT^^^^M Wee President, Development Carla A. Hills*t Elise Carlson Lewis Joseph S. Nye Jr. Wee President, Membership Fareed Zakaria and Fellowship Affairs JJLt\>,Zm James M. Lindsay Term Expiring 2010 j^YESS Wee President, Director of Studies, Peter Ackerman Maurice R. Greenberg Chair Charlene Barshefsky Nancy E. Roman Stephen W. Bosworth Wee President and Director, Washington Program Tom Brokaw yJ§ David M. -

The Handbook of Journalism Studies

THE HANDBOOK OF JOURNALISM STUDIES This handbook charts the growing area of journalism studies, exploring the current state of theory and setting an agenda for future research in an international context. The volume is structured around theoretical and empirical approaches, and covers scholarship on news production and organizations; news content; journalism and society; and journalism in a global context. Empha- sizing comparative and global perspectives, each chapter explores: • Key elements, thinkers, and texts • Historical context • Current state-of-the-art • Methodological issues • Merits and advantages of the approach/area of studies • Limitations and critical issues of the approach/area of studies • Directions for future research Offering broad international coverage from top-tier contributors, this volume ranks among the fi rst publications to serve as a comprehensive resource addressing theory and scholarship in journalism studies. As such, The Handbook of Journalism Studies is a must-have resource for scholars and graduate students working in journalism, media studies, and communication around the globe. A Volume in the International Communication Association Handbook Series. Karin Wahl-Jorgensen is Reader in the Cardiff School of Journalism, Media, and Cultural Stud- ies, Cardiff University, Wales. Her work on media, democracy, and citizenship has been pub- lished in more than 20 international journals as well as in numerous books. Thomas Hanitzsch is Assistant Professor in the Institute of Mass Communication and Media Research at the University of Zurich. He founded the ICA’s Journalism Studies Division and has published four books and more than 50 articles and chapters on journalism, comparative com- munication research, online media, and war coverage. -

Producer Proof

NOMINEES FOR THE 35th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be Announced at a Gala Event at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Nominees include new categories for News & Documentary Programming in Spanish William J. Small, Former CBS Washington Bureau Chief and Former President of NBC News to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 15, 2014 – Nominations for the 35th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 30th, 2014, at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy® Awards will be presented in 43 categories, including the first-ever categories reserved for news & documentary programming in Spanish. William J. Small, the legendary CBS News Washington Bureau chief from 1962-1974, and later President of NBC News, will receive the prestigious Lifetime Achievement award at the 35th Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards. "Bill Small is an icon in the television news industry," said Chuck Dages, Chairman, NATAS. "As Bureau Chief of the CBS Washington News office throughout the 60's and 70's, he was paramount in the dramatic evolution of network news that continues today. Recruiting the likes of Dan Rather, Bob Schieffer, Bill Moyers, Ed Bradley, Diane Sawyer and Lesley Stahl among many others, he changed not only who we watched each evening but how.” Yangaroo, Inc. -

Annual Report ^ ^

COUNCIL^ FOREIGN RELATIONS 200Annual Report 8^^"^ Annual Report July 1, 2007 – June 30, 2008 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 fax 212.434.9800 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 tel 202.509.8400 fax 202.509.8490 www.cfr.org [email protected] Officers and Directors, 2008–2009 OFFICERS DIRectoRS Carla A. Hills Suzanne E. Helm Term Expiring 2009 Term Expiring 2010 Term Expiring 2011 Co-Chairman Vice President, Development Madeleine K. Albright Peter Ackerman Henry S. Bienen Robert E. Rubin Kay King Richard N. Foster Charlene Barshefsky Ann M. Fudge Co-Chairman Vice President, Washington Program Maurice R. Greenberg Stephen W. Bosworth Richard C. Holbrooke Richard E. Salomon L. Camille Massey Henry R. Kravis Tom Brokaw Colin L. Powell Vice Chairman Vice President, Membership, Joseph S. Nye Jr. Frank J. Caufield Joan E. Spero Richard N. Haass Fellowship, and Corporate Affairs James W. Owens Ronald L. Olson Vin Weber President Gary Samore Fareed Zakaria David M. Rubenstein Christine Todd Whitman Janice L. Murray Vice President, Director of Studies, Maurice R. Greenberg Chair Senior Vice President, Treasurer, Term Expiring 2012 Term Expiring 2013 Richard N. Haass and Chief Operating Officer Lisa Shields ex officio David Kellogg Vice President, Communications Fouad Ajami Alan S. Blinder Senior Vice President and Publisher and Marketing Sylvia Mathews Burwell J. Tomilson Hill Kenneth M. Duberstein Alberto Ibargüen Nancy D. Bodurtha Lilita V. Gusts Secretary Stephen Friedman Shirley Ann Jackson Vice President, Meetings Carla A. Hills George E. Rupp Irina A. Faskianos Jami Miscik Richard E. -

The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Alison Owings, and the Experience of Second-Wave

Reality and Perception of Feminism and Broadcast 1968-1977: The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Alison Owings, and the Experience of Second-Wave Feminism in Broadcast News A thesis presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sarah L. Guthrie June 2010 © 2010 Sarah L. Guthrie. All Rights Reserved. This thesis titled Reality and Perception of Feminism and Broadcast 1968-1977: The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Alison Owings, and the Experience of Second-Wave Feminism in Broadcast News by SARAH L. GUTHRIE has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Patrick S. Washburn Professor of Journalism Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract Guthrie, Sarah L., M.A., June, 2010, Journalism Reality and Perception of Feminism and Broadcast 1968-1977: The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Alison Owings, and the Experience of Second-Wave Feminism in Broadcast News (132 pp.) Director of thesis: Patrick S. Washburn This thesis examined the media portrayal of liberation and feminism in The Mary Tyler Moore Show (TMTMS) during second-wave feminism and contrasted it with the real-life experiences of Alison Owings, who worked in broadcast news at the same time. Interviews with Owings, Susan Brownmiller (a prominent feminist) and Treva Silverman (the primary female writer for TMTMS) were conducted, Owings’s personal files were mined for primary source documents from the period, and numerous popular and scholarly books and articles addressing the impact of TMTMS were studied. -

The State of the News Media 2008 Executive Summary

Overview – Intro Intro By the Project for Excellence in Journalism The state of the American news media in 2008 is more troubled than a year ago. And the problems, increasingly, appear to be different than many experts have predicted. Critics have tended to see technology democratizing the media and traditional journalism in decline. Audiences, they say, are fragmenting across new information sources, breaking the grip of media elites. Some people even advocate the notion of “The Long Tail,” the idea that, with the Web’s infinite potential for depth, millions of niche markets could be bigger than the old mass market dominated by large companies and producers. 1 The reality, increasingly, appears more complex. Looking closely, a clear case for democratization is harder to make. Even with so many new sources, more people now consume what old media newsrooms produce, particularly from print, than before. Online, for instance, the top 10 news Web sites, drawing mostly from old brands, are more of an oligarchy, commanding a larger share of audience, than in the legacy media. The verdict on citizen media for now suggests limitations. And research shows blogs and public affairs Web sites attract a smaller audience than expected and are produced by people with even more elite backgrounds than journalists. 2 Certainly consumers have different expectations of the press and want a changed product. But more and more it appears the biggest problem facing traditional media has less to do with where people get information than how to pay for it — the emerging reality that advertising isn’t migrating online with the consumer. -

Board Election Features Packed Slate of Candidates

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • July-August 2015 Board Election Features Packed Slate of Candidates Last spring, an email was sent to Members Advisory Council whose ture events as they unfold, and give members calling for nominations of main charge will be to advance ideas them meaning and perspective. candidates for the 2015 board of gov- and programs that further solidify I plan to vote and I hope you will ernors’ election. Thanks to you and the OPC’s position as an important too. the nominating committee, we have a resource for journalists. Areas of - Brian Byrd slate of 17 active members running for focus include press safety and free- Chairman, board seats, out of which 12 will be se- dom, membership, Elections Procedure Committee lected. In addition, four candidates are events, awards and running for two open associate board others. Details and ELECTION REMINDERS seats. Each and every one of them are election results will exceptional in backgrounds, experi- be announced and ● Watch your email inbox for ences and accomplishments, making discussed at the a message from the OPC this one of the most competitive elec- upcoming annual that will include a link to your tions in recent memory. The strength meeting on Tues- electronic ballot on Balloteer, a and diversity of this slate is, in no small day, Aug. 25 at 6:00 secure on line voting service. part, a reflection of the revised system p.m. at Club Quarters, 40 West 45th ● To log in, use the email in which OPC elects its board of gov- St. -

30Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARDS

IMMEDIATE RELEASE 30th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCED AT NEW YORK CITY GALA Lifetime Achievement Award Presented to Barbara Walters President’s Award Presented to CNN Doc Unit Special Tributes to Walter Cronkite and Don Hewitt New York, N. Y. – September 21, 2009 (revised 10.05.09)– The 30th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards were presented by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences this evening at a gala ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City. More than 800 media industry executives, journalists, and producers attended the event which honors outstanding achievement in television journalism by individuals and programs, distributed via broadcast, cable and broadband. A Lifetime Achievement Award was presented to Barbara Walters, longtime ABC News correspondent and creator and co-host of The View. Katie Couric, anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News With Katie Couric, paid tribute to Walters, and Walters’ lifetime achievement Emmy was presented by ABC News president David Westin. CNN Productions, the documentary unit of CNN, was honored with the President’s Award for their distinguished contribution to the craft of documentary filmmaking. Jon Klein, the president of CNN, accepted the award, which was presented by NATAS chairman Herb Granath. Walter Cronkite and Don Hewitt, two broadcast journalism legends who passed away in 2009, received special tributes. Walter Cronkite’s son Chip Cronkite spoke about his father. And Don Hewitt’s wife, the journalist Marilyn Hewitt, spoke about her late husband. Bill Small, Chairman of the News & Documentary Emmy Awards, presided over the Cronkite and Hewitt presentations.