Update on the Role and Status of Women Correspondents in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Bolton's Budget Talks Collapse

J u N anrbpBtpr Hrralb Newsstand Price: 35 Cents Weekend Edition, Saturday, June 23,1990 Manchester — A City of Village Charm Bolton’s budget talks collapse TNT, CASE fail to come to terms.. .page 4 O \ 5 - n II ' 4 ^ n ^ H 5 Iran death S i z m toll tops O "D 36,1 Q -n m rn w State group S o sends aid..page 2 s > > I - 3 3 CO 3 3 > > H ■ u ^ / Gas rate hike requested; 9.8 percent > 1 4 MONTH*MOK Coventry will be Judy Hartling/Manchealsr Herald BUBBLING AND STRUGGLING — Gynamarie Dionne, age 4, tries for a drink from the affected.. .page 8 fountain at Manchester’s Center F*ark. Her father, Scott, is in the background. Moments later, he gave her a lift. ,...___ 1 9 9 0 J u p ' ^ ‘Robin HUD .■ '• r ■4 given stiff (y* ■ • i r r ■ prison term 1 . I* By Alex Dominguez The Associated Press BALTIMORE “Robin HUD,” the former real estate agent who claimed she stole about $6 million from HUD to help the poor, was sentenced Friday to the maximum prison term of nearly four years. t The Associated Press U.S. District Judge Herbert Murray issued the 46- month sentence at the request of the agent, Marilyn Har rell, who federal officials said stole more from the government than any individual. “I will ask you for the maximum term because I DEATH AND SURVIVAL — A father, above, deserve it,” Harrell told the judge. “I have never said what I did was right. -

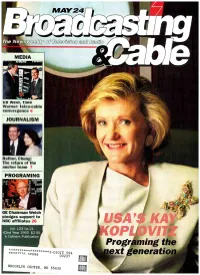

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

101111Ne% 11%01% /111 M6ipirlivfaiwalliellhoelp41 11111

Group W plotting course for its satellite expertise By Bill Dunlap is exceptionally well positioned has two or three sidebands Group W Radio Sales, has to make such a move—better available. We're thinking in a offices in eight top markets and NEW YORK Group W so, for instance, than Turner lot of different directions. will start developing network Radio, the II-station radio Broadcasting's CNN Radio. Where it may take us, if any- sales expertise this month with group taking the first step "As much as I care to say where, Idon't know." he said. its Quality Unwired Radio toward networking this month about it right now" Harris said, What Harris didn't say was Environment (QURE), an un- with an unwired national spot "is that we have alot of satellite that Group W Radio also owns wired commercial network service for its own stations, is at experience with Muzak. We all news or news-talk stations in reaching almost 30 percent of least thinking about providing have 200 downlinks around the such major markets as New the U.S. population. a network news service. United States. We own them all York, Los Angeles, Chicago, "Over the years, we have While Group W Radio Presi- and we're in the process of Philadelphia and Boston and continued to look at where dent Dick Harris plays down enlarging them. that its parent company owns 'there might be a place for us in the likelihood of such aventure "Because of our television half of Satellite News Channels, networking," Harris said. -

Opinion | Sylvia Chase and the Boys' Club of TV News

SUNDAY REVIEW Sylvia Chase and the Boys’ Club of TV News When we started at the networks in the early ’70s, most of us tried to hide our gender. Sylvia spoke out. By Lesley Stahl Ms. Stahl is a correspondent for “60 Minutes.” Jan. 12, 2019 Back in the early 1970s, the TV network news organizations wanted to show the world that they were “equal opportunity employers.” And so, CBS, ABC and NBC scoured the country for women and minorities. In 1971, Sylvia Chase was a reporter and radio producer in Los Angeles, and I was a local TV reporter in Boston. CBS hired her for the New York bureau; I was sent to Washington. Sylvia, who died last week at age 80, and I were CBS’s affirmative action babies, along with Connie Chung and Michele Clark. To ensure we had no illusions about our lower status, we were given the title of “reporter.” We would have to earn the position of “correspondent” that our male colleagues enjoyed. We were more like apprentices, often sent out on stories with the seniors, like Roger Mudd and Daniel Schorr. While we did reports for radio, the “grown-ups” — all men — did TV, but we were allowed to watch how they developed sources, paced their days and wrote and edited their stories. Up until then, most women in broadcast journalism were researchers. At first, the four of us in our little group were grateful just to be in the door as reporters. Things began to stir when the women at Newsweek sued over gender discrimination. -

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 14, folder “5/12/75 - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 14 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Vol. 21 Feb.-March 1975 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY PARC, THE PHILADELPHIA ASSOCIATION FOR RETARDED CITIZENS FIRST LADY TO BE HONORED Mrs. Gerald R. Ford will be citizens are invited to attend the "guest of honor at PARC's Silver dinner. The cost of attending is Anniversary Dinner to be held at $25 per person. More details the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, about making reservations may be Monday, May 12. She will be the obtained by calling Mrs. Eleanor recipient of " The PARC Marritz at PARC's office, LO. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

Matthew C. Ehrlich (August 2015) 119 Gregory Hall, 810 S

Matthew C. Ehrlich (August 2015) 119 Gregory Hall, 810 S. Wright St., Urbana IL 61801; 217-333-1365 [email protected] OR [email protected] I. PERSONAL HISTORY AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Academic Positions Since Final Degree Currently Professor of Journalism and Interim Director of the Institute of Communications Research, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 1992: Appointed Assistant Professor. 1998: Promoted to Associate Professor with tenure. 2006: Promoted to Professor with tenure. 2015: Appointed Interim Director, Institute of Communications Research. 1991-1992: Assistant Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Oklahoma. Educational Background 1991: Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Institute of Communications Research. 1987: M.S., University of Kansas, School of Journalism and Mass Communications. 1983: B.J., University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism. Journalism/Media Experience 1987-1991, WILL-AM, Urbana, IL. Served at various times as Morning Edition and Weekend Edition host for public radio station; hosted live call-in afternoon interview program; created and hosted award-winning weekend news magazine program; produced spot and in-depth news reports; participated in on-air fundraising. 1985-1987, KANU-FM, Lawrence, KS. Served as Morning Edition newscaster for public radio station; produced spot and in-depth news reports. 1985-1986, Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Kansas. Supervised students in university’s radio and television stations and labs, including KJHK-FM. 1984-1985, KCUR-FM, Kansas City, MO. Produced spot and in-depth news reports for public radio station; hosted midday news magazine program. 1983-1984, KBIA-FM, Columbia, MO. Supervised University of Missouri journalism students in public radio newsroom; served as evening news host and editor. -

Possible Name Change Awaits CSUF Schools

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, FULLERTON Avner Ofer INSIDE journeys to India and explores the 2 n CALENDAR: ASP screens “The Golden Temple Blair Witch Project” Thursday in Amritsar 5 nOPINION: A glance at modern folk- lore through television and film —see Travel page 4 VO L UME 69, I SSUE 15 TUESDAY O CTO B E R 5, 1999 Diet pills Hawk’s-eye view Possible name compete in fat change awaits nHEALTH: Experts dis- CSUF schools cuss benefits and risks of various fat-loss nCAMPUS: Senate ence in their decision. Sandra Sutphen, professor of political science, said it products on the mar- voted to rename the will not make any difference at all. “It is just a name change,” Sutphen ket today seven schools on said. “People might be worried about new stationary but that is about it.” BY LA RUE V.BABER campus to colleges Staff Writer Before the plan goes into effect, BY RITA FREEMAN there is a brief waiting period of a Staff Writer week. Then it is transmitted formally Magic pills sealed with promises to the president for his approval. Once to kill cravings, boost metabolisms Cal State Fullerton’s individual signed by the president, the resolution and suppress appetites crowd the schools may soon change their names goes into effect. health consumer’s market. to colleges if President Milton Gordon Currently, 13 CSU campuses and These diet products come in many signs a proposal, Academic Senate nine UC campuses use the name col- forms. Some are prescription only Document 99-117, which the senate lege. -

VITAL SIGNS Myopic Media

VITAL SIGNS ed, "There is, I think, a bias within the ing told President Clinton, "If we could MEDIA media toward dealing with problems in a be one-hundredth as great as you and way that involves spending more money. Hillary Rodham Clinton have been in ... I think that there is a tendency the White House, we'd take it right now among many [in the media] to feel that and walk away winners. Tell Mrs. the best solution is a government solu Clinton we respect her and we're pulling tion. Youmay call that liberal." for her." Walter Cronkite recently advo Mike Wallace of CBS News sharply cated a new political system. He told Los Myopic Media disagreed, denying the existence of any Angeles Times Magazine, "We may have by Marc Morano liberal bias in the news media and using to find some marvelous middle ground the election of recent Republican Presi between capitalism and communism." dents to prove it. According to him, the Other journalists at the dinner were he 1996 Radio and Television Cor media could not be all-powerful and lib not happy with Goldberg's critique. An Trespondents Dinner in Washington, eral because Republicans have been so drea Mitchell of NBC News stated, "I re D.C., in March may be remembered for successful at winning the White House. ally disagree with that and I think Eric shock-jock Don hnus's tasteless diatribe, "When people suggest there is a bias in Engberg is a terrific correspondent." but the real discord occurred behind the the media and we have all of this power Judy Woodruff of CNN cautioned that, scenes, hiterviews I conducted with top and then of course the bias is always sup "I think Mr. -

Newspro Cuts a Wide Swath

December 2014 Entries Go to Great Lengths Longform Awards Submissions Reach New Heights Page 10 Footing the Innovation Bill Grant Programs Out to Blaze New Trails Page 12 A Children’s Cause Is Lost The Journalism Center on Children & Families Closes Its Doors Page 14 Our Top 10 J-Schools to Watch Mizzou Takes the No. 1 Spot Once Again 12 in TV News Page 16 Page 4 Plain Speaking on Integrity Author and Educator Charles Lewis Calls for Gravitas in Local Reporting Page 23 14np0054.pdf RunDate:12/15/14 Full Page Color: 4/C FROM THE EDITOR Loss or Gain, It’s Change e subject matter of this issue of NewsPro cuts a wide swath. We feature stories about disruptive change, about loss and gain, and about tradition and innovation. In essence, the terms that best describe the chaotic world of journalism. CONTENTS Our annual “12 to Watch in TV News” feature o ers a look at the professionals who are 12 TO WATCH IN TV NEWS ................. 4 in positions to make their imprint on — and in some cases change — the TV news business. This Year’s Wrap-up of the Pivotal Players You’ll nd among this year’s choices both the expected and a few fresh surprises. in the News Business On the journalism awards front, our piece discovers that the recession-related drop-o in submissions appears to be over for good, with programs reporting a notable gain in entries, AWARDS PROGRAMS ADAPT ........... 10 particularly of the longform variety — a development that has caused a dire need for change in Longform and Multimedia Entries Change the the way those organizations judge accomplishment. -

Alumni Newsletter May/June 2016 Commissioning – Valley Forge Military College

Alumni Newsletter May/June 2016 Commissioning – Valley Forge Military College We want to congratulate the Valley Forge Military College Army ROTC Commissioning Class of 2016. 2LT Samantha Barnes 2LT Jared Knightley 2LT Bryan Beatty 2LT Stephen Mayone-Paquin 2LT Adrian Cabiles 2LT Alexander Castueras 2LT Philip McCusker 2LT Tyler Eccles 2LT Henry Richardson 2LT Sky Faneco 2LT Joshua Rosen 2LT Cynthia Filpo-Diaz 2LT Ryan Sevret 2LT Thomas Gagnon 2LT Jennifer Sprengelmeyer 2LT Caleb Gillett 2LT Alex Hammond 2LT Maxwell Thomas 2LT Jason Hang 2LT Rebecca Timm 2LT Aaron Harbaugh 2LT Marina Torchia 2LT Noreeza Khan 2LT Benjamin White 2LT Tristan Kidney The presiding officer for the Valley Forge Military College 2016 Army ROTC Commissioning was Major General William H. Johnson, USA, Retired, Senior United States Army Reserve Ambassador. Major General Johnson was commissioned a Second Lieutenant, Armor, upon his graduation from North Georgia College and entered active duty in 1972. His professional military education includes Armor Officer Basic Course, Rotary Wing Aviation School, Transportation officer Advanced Course, United States Army Command and General Staff College and United States Army War College. We were honored to have such a distinguished Military Commander present to give the Oath of Office to our newest Army officers and VFMC graduates. Assisting Major General Johnson in officiating the marvelous ceremony were Professor of Military Science LTC David Key, USA and Senior Military Science Instructor MSG John Cuevas, USA. Commencement VFMC 2016 On May 20, 2016 Commencement Ceremonies were held for Valley Forge Military College when 102 and cadets and students took the next step into their futures by attaining their Association Degree.