Objectif Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Half Sized

Nov 2010 e u g o l a t a c & r e t t e Paul Skilleter enjoying Nigel Webb’s Mike Hawthorn Jaguar Mk1 recreation l PaulSkilleterBooks/PJPublishingLtd s 38,FarmLaneSouth BartononSea NEWMILTON w Hampshire Tel:01425612669 e e-mail:[email protected] Web:www.PaulSkilleterBooks.Co.Uk n November2010 2 ListerJaguarBookLaunch The book was launched at Race Retro, Stoneleigh, 12 -14 March 2010! When Ted Walker and I set out to record the history of Lister using Ted’s Ferret Fotographics archives as the basis, we certainly didn’t realise that what began as a relatively simple photo-book would turn into the major work that it did. But when I approached Brian Lister and told him of our intentions, he soon became personally interested in the project, and began to uncover all sorts of fascinating documents and pictures. Augmented by more period photographs from his former chief mechanic Edwin ‘Dick’ Barton, the book grew into a full- blown history of Lister, covering all Brian’s cars and telling the story of the family company, George Lister Engineering (which still flourishes today, incidentally, though it ceased to have any connection with cars after the team retired in 1959). The final cog in the mechanism, as it were, was John Pearson. As I say in the book’s introduction, John has had a longer continuous relationship with Listers than anyone else, and when I first came onto the scene around 1966, John was one of the first Jaguar racing people I met. I soon learned that for several years from 1962 he had been mechanic to John Coundley, that prolific owner and driver of Lister-Jaguars, and before that had seen the earliest Listers perform and watched Lister works driver Archie Scott Brown in his prime. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

September 2012 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kye Wankum

September 2012 www.pcaucr.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kye Wankum ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION Kye Wankum [email protected] September 2012 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emily Atkins News [email protected] Zone 1 Dates & Notes 10 First Annual Porsche Show & Swap Meet 10 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Garth Stiebel Street Survival School - Isi Papodoupulos 36 [email protected] 2012 Nominating Committee Seeking Recomendations 55 UCR TECHNICAL EDITOR Departments George O’Neill President’s Message - Mario Marrello 4 [email protected] UCR Calendar of Events 5 UCR PHOTO EDITOR UCR Socials - Isabel Starck 6 Eshel Zweig at [email protected] New Members - Angie & Mark Herring 7 Membership Anniversaries - Angie & Mark Herring 7 UCR CLUB PHOTOGRAPHER Editor’s Ramblings - Kye Wankum 8 Michael A. Coates The Way We Were - UCR Historical - John Adam 9 CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS UCR Driver Education 10 Graham Jardine Letters to the Editors 11 Ken Jensen UCR Fun Runs - David Forbes 52 Ronan McGrath The Mart 56 Andreas Trauttmansdorff Board Meeting Minutes from July 3, 2012 - Isabel Starck 59 Eshel Zweig Who’s Who In Upper Canada 61 PUBLISHER Advertiser Index 62 Richard Shepard at [email protected] Features ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATION The Targa Florio - Ronan McGrath 16 AND BILLING The 2012 PCA UCR Concours - Chris Ralphs 22 Sheri and Neil Whitlock 905-509-9692 or Email: [email protected] The ALMS Experience - Robert Moniz 28 Classic Porsche - Robert Eberschlag 40 AD & COPY DEADLINE Focus - Essential Ingredient In Driver Education - Garth Stiebel 46 30 Days prior to publication date; e.g. June 1st for the July Advertiser Of The Month: The Seidman Kaufman Group 48 issue of Provinz; July 1st for the August issue of Provinz. -

Auto Racing 1 Auto Racing

Auto racing 1 Auto racing Auto racing Sebastian Vettel overtaking Mark Webber during the 2013 Malaysian Grand Prix Highest governing body FIA First contested April 28, 1887 Characteristics Mixed gender Yes Categorization Outdoor Auto racing (also known as automobile racing, car racing or motorcar racing) is a motorsport involving the racing of automobiles for competition. History The beginning of competition Motoring events began soon after the construction of the first successful gasoline-fueled automobiles. The first organized contest was on April 28, 1887, by the chief editor of Paris publication Le Vélocipède, Monsieur Fossier. It ran 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from Neuilly Bridge to the Bois de Boulogne. It was won by Georges Bouton of the De Dion-Bouton Company, in a car he had constructed with Albert, the Comte de Dion, but as he was the only competitor to show up it is rather difficult to call it a race. Another solo event occurred in 1891 when Auguste Doriot and Louis Rigoulot of Peugeot drove their gasoline-fueled Type 3 Quadricycle in the bicycle race from Paris–Brest–Paris. By the time they reached Brest, the winning cyclist Charles Terront was already back in Paris. In order to publicly prove the reliability and performance of the 'Quadricycle' Armand Peugeot had persuaded the organiser, Pierre Giffard of Le Petit Journal, to use his network of monitors and marshalls to vouchsafe and report the vehicle's performance. The intended distance of 1200 km had never been achieved by a motorised vehicle, it being about three times further than the record set by Leon Serpollet from Paris to Lyon.[1][2] Auto racing 2 Paris–Rouen: the world's first motoring contest On July 23, 1894, the Parisian magazine Le Petit Journal organized what is considered to be the world's first motoring competition from Paris to Rouen. -

23 CHENARD & 2 978 Cm³ 2 209,536 A

LE MANS RACES HISTORY___________________________________________ Distance Winner Biennial Year Manufacturer Engine cubic cap. Drivers Av. speed Fastest lap (race) Winner Triennial Cup Dép Ab Comments km Cup 1923 CHENARD & 2 978 cm³ 2 209,536 A. Lagache 92,064 F. Clément 33 3 The circuit (17,262 km) went through Pontlieue. Only the WALCKER 4 cyl. en ligne R. Léonard BENTLEY Sport Création driver could carry out repairs. « Sport » 9’39’’ - 107,328 km/h 1924 BENTLEY 2 995 cm³ 2 077,340 J. Duff 86,555 A. Lagache 41 23 The cars had to cover 20 laps with the hood up. « Sport » 4 cyl. en ligne F. Clément CHENARD & WALCKER Création 9’19’’ - 111,168 km/h 1925 LORRAINE 3 473 cm³ 2 233,982 G.de Courcelles 93,082 A. Lagache CHENARD & WALCKER CHENARD & 49 28 Race Control moved to Les Hunaudières. First American DIETRICH 6 cyl. en ligne A. Rossignol CHENARD & WALCKER R. Senéchal WALCKER participation (Chrysler). B3-6 9’10’’ A. Loqueneux R. Glaszmann 112,987 km/h M. de Zuniga Distance Winner Biennial Year Manufacturer Engine cubic cap. Drivers Av. speed Fastest lap (race) Winner Triennial Cup Dép Ab Comments km Cup 1926 LORRAINE 3 446 cm³ 2 552,414 R. Bloch 106,350 G.de Courcelles O.M. 665SS O.M. 665SS 41 24 First grandstands built and a car park for 3000 cars. The DIETRICH 6 cyl en ligne A. Rossignol LORRAINE DIETRICH Superba Superba 100 km/h average exceeded for the first time. The RN 138 B3-6 9’03’’ F. Minoia F. -

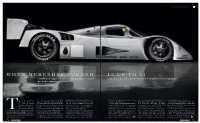

W H E N M E R C E D E S T U R N E D I T U P T O

SAUBER-MERCEDE S C 1 1 When Mercedes turned it up to 1 1 Twenty years ago the marque teamed up with Sauber to produce the C11 – a car that ruled all and influenced a return to F1 BY GARY WATKIN S he first pure-bred The C11 was the fruit of an unlikely with Mauro Baldi and Jean-Louis Schlesser. One Pointed Star was soon back at the pinnacle of the engines, it was natural that he should look to say, they didn’t take a lot of convincing.” Mercedes-Benz racer for relationship. A back-door deal to supply engines of the five drivers to notch up victories in the sport as an engine supplier. Mercedes’ road-car range for a replacement. The official line was that the engine was 35 years. A World to the Swiss Sauber sports car squad in the mid- C11 was a young Schumacher, who’d been The tiny Sauber team from Hinwil had made He reckoned the 5-litre M117, in lightly developed for racing by renowned Swiss tuner Championship winner. 1980s paved the way for Mercedes to return plucked from Formula 3 to become part of a contact with Mercedes in 1981. A young road turbocharged form, would be the ideal Heine Mader. But Welti explains that this The car that gave us officially to motor sport in ’88. For 1990, the junior programme conceived by new Mercedes car suspension engineer by the name of Leo Ress powerplant for the Group C fuel formula. arrangement was a smokescreen. Michael Schumacher. The partnership produced the first bespoke Mercedes motor sport boss Jochen Neerpasch. -

CFD-Analysis of the Aerodynamic Prop- Erties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR

CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic prop- erties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR Bachelor’s thesis in Applied Mechanics ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 Bachelor thesis nr 2015:07 Bachelor’s project TMEX02-15-15 CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic properties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR Comparison of drag- and lift forces generated when the Mercedes’ air brake is deployed ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic properties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR. Comparison of drag- and lift forces generated when the Mercedes’ air brake is de- ployed. ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER © ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER, 2015. Supervisor: Emil Ljungskog Examiner: Professor Lennart Löfdahl Bachelor’s project TMEX02-15-15 Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Telephone +46 31 772 1000 Cover: Streamlines around the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR travelling at 120 kph. Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 iv Abstract Mercedes-Benz was one of the most prominent car manufacturers in motorsport in the 50’s. In 1955 they participated with the model 300 SLR in the Le Mans 24- hour race. What made this model standing out was the mounted air brake, which would compensate for the weaker drum brakes compared with competing models’ disc brakes. -

Mercedes-Benz 300SL

Mercedes-Benz 300SL From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Mercedes-Benz 300SL Manufacturer Mercedes-Benz Also called Mercedes Benz 300 SLR 2-door coupe Production 1952-1963 Predecessor none Successor Mercedes-Benz 230SL Body style 2 door coupé, roadster Engine Mercedes 2995cc, SOHC Transmission 4-speed MANUAL Wheelbase 94.5 in Length 178 in Width 70.5 in Height 51.1 in Curb weight 2351 lbs The Mercedes-Benz 300SL is a two-seat, closed sports car with characteristic gull-wing doors, and later, offered as an open roadster. Built by Daimler-Benz AG and internally numbered W198, the road version of 1952 was based (somewhat loosely) on the company's highly successful competition-only sports car of 1950, the Mercedes-Benz 300SL (W194) which had less power, as it still had carburetors. This model was suggested by Max Hoffman. Because it was intended for customers whose preferences were reported to Hoffman by dealers he supplied in the booming, post-war American market, it was introduced at the 1954 New York Auto Show—unlike previous models introduced at either the Frankfurt or Geneva shows. The 300SL was best known for both its distinctive gullwing or butterfly wing doors and for being the first-ever gasoline-powered car equipped with fuel injection directly into the combustion chamber. The gullwing version was available from March 1955 to 1957. In Mercedes-Benz fashion, the "300" referred to the engine's cylinder displacement, in this case, three liters. The "SL", as applied to a roadster, stood for "Sport Leicht" or "Sport Light." More widely produced (25,881 units) and starting in 1954 was the similar looking 190SL with a 105hp 4cyl engine, available only as roadster (or with an additional hardtop, as Coupe Roadster). -

283647168.Pdf

Racecar Engineering The leading motorsport technology publication since 1990 1 Volume 25 Volume 25YEARS OF INSIGHT January 2015 • Vol 25 No1 • www.racecar-engineering.com • UK £5.95 • US $14.50 9 7 7 0 9 6 1 1 0 9 1 0 World Champion! 4 0 Why Mercedes dominated 1 Formula 1 in 2014 NASCAR drafting in CFD W05 Mercedes Sauber C33 January 2015 Sauber C33 Aero investigation Scion Racing tC Swiss F1 team pays the price NASCAR studies what happens Examining the technical for late delivery of power units when stockcars slipstream challenges of US drifting RCE Jan Cover.indd 1 24/11/2014 18:08 NEW The Dry Sump Vacuum Race Hose ProPLUS Xtreme A high flowing, smooth bore, PTFE tube with external convolutions for flexibility. No internal convolutions An engineered design with an that can cause flow restrictions. externally wound stainless steel wire A choice of lightweight braids: that provides great vacuum support XM - XtraTemp Mono or XK - Aramid and tight bend capability. An exceptional achievement in race hose technology... Perhaps perfection. ™ Go to www.xrp.com to learn more about The evolution in FLUID HORSEPOWER continues... the complete XRP ProPLUS Race Hose™ product line. Like us on Follow us on Facebook/XRPinc Instagram @XRPracing USA XRP, Inc. [email protected] tel 562 861 4765 fax 562 861 5503 ® EUROPE JLS Motorsport [email protected] tel 44 (0) 121 525 5800 fax 44 (0) 121 525 4833 THE XTREME IN RACECAR PLUMBING Untitled-89 1 08/10/2014 14:08 CONTENTS – JANUARY 2015 – Volume 25 Number 1 COVER STORY TECHNICAL 8 Mercedes AMG W05 Hybrid -

1955 Le Mans Disaster

Days that Shook the F1 World – 1955 Le Mans Disaster Hello, we have reached the end of our second foray into Formula 1 history, picking out the days that have shaped the sport we know and love today. This last edition picks out a specific date from the 1950s – June 11th 1955. Although not strictly a Formula 1 race, the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1955 had an enormous impact on all categories of motorsport, for the worst possible reason. June 11th is known as one of the blackest days in racing history due to the terrible crash that took place. In those days, most current F1 drivers would be taking part in the endurance event, and the battle at the front was between Hawthorn, Fangio and Pierre Levagh. Levagh was driving for Mercedes, along with Stirling Moss and Fangio. The race started well, but after about two hours, the accident happened. Levagh’s Mercedes came into contact with the Austin‐Healey of Lance Macklin, and due to the ramp‐shaped rear of the car, was launched into the air. The Mercedes hit the mound of earth designed to protect the spectators, and was somersaulted over the top and directly into the crowd. The car had a high magnesium content, and as the fuel tank split and ignited, the entire thing burst into intense flames. Levagh had already been thrown from the car and killed, and many, many spectators suffered the same fate. When rescuers attempted to put the flames out with their water extinguishers, it made things worse as it met the magnesium fuelled flames. -

AGENTUR Sie Suchen Ein Oldtimer Oder Haben Eins Anzubieten!

Sie suchen ein Oldtimer oder haben eins Anzubieten! ,,Bj. Modell und Preis angeben‘‘ Oldtimer & Exclusiv Cars - email schicken und Sie bekommen umgehend AGENTUR Bilder zum entsprechenden FZ dazu. [email protected] Name: Helmut Binder City: Vācu Kalni - Brēmenes iela 38 C Aktuelle Fahrzeuge A bis Z LV / Tel: 00371 - 26489007 Email: [email protected] Freitag, 16. Mai 2014 Country: LatvijaLV / Telefon: -5015 Salaspils www: oltimer-agent.com Englische Fahrzeuge Austin 1933 Austin Seven 04 very good basis for restoration 7.000.-€ 1950 AUSTIN 04 Austin left the club about 40 pieces. Version of the left-hand drive 13.500.-€ SHEERLINE only 3 pieces. (Mine is the third). Auto complete, chairs and sofa on A125 LHD renewal, all documents, suspension done, a set of new spark plugs, a lot of parts in stock. Even in the autumn engine burn to the touch, now lost somewhere spark. Austin in its long history had only two owners.. ............. 1960 Austin Healey 04 full restored 45 000 Euro BN4 excellent condition 1960 Austin Healy 04 new exhaust system price 33 000 BN4S new rims Euro in restoration progres or full body work its done complite restored 60 000 Euro 1963 Austin Healey 04 PERFECT RESTORED CAR!!!! 47 000.-€ 1964 Austin Healey E phase 1 1390 examples produced. 64 000 € 3000 mk3 U Colorado red, black leather trim, excellent restoration, Italian plate, ASI certificate. 1965 Austin Cooper S 04 1275cc, car serviced, perfect interior and original never restored, 40 000 Euro orig Minilite wheels, wheels Yokohama, English certificate, new brakes, new battery, sports exhaust, very fast, beautiful 1966 Austin Healey 04 matching numbers 26 500 Euro 3000 MK III complete, engine works very good car for restoration 1969 AUSTIN 04 100% original, together with the original radio and hub caps on the 10 500.- € HEALEY Sprite wheels and steering wheel. -

Vnuk Impact Analysis Combined Report

Vnuk Impact Analysis Combined Report 23 August 2019 Matt Kirkpatrick Vnuk Impact Analysis – Aggregated report Contents Overview 3 Purpose 3 Executive Summary 3 Analysis Chronology 7 Format of this report 8 Original Vnuk impact analysis 9 Effect of introducing a cap on third party bodily injury claims 10 Effect of Increasing Motor Sports exposure / Personal Injury Discount Rate 11 External Peer review by Grant Thornton UK LLP 12 GAD’s response to the external peer review 13 At GAD, we seek to achieve a high standard in all our work. We are accredited under the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries’ Quality Assurance Scheme. Our website describes the standards we apply. 2 Vnuk Impact Analysis – Aggregated report Overview The Government Actuary’s Department has been working with the Department for Transport to investigate the potential impact in the United Kingdom of a judgment by the European Court of Justice regarding compulsory motor insurance. This report combines all of the analysis that has been carried out since 2017, including an external peer review by Grant Thornton UK LLP. Purpose 1.1 This report has been prepared by the Government Actuary’s Department (‘GAD’) at the request of the Department for Transport (‘DfT’). The report provides a single document which contains all of the analysis carried out by GAD between 2017 and 2019 exploring the potential impact of the 2014 judgment by the European Court of Justice regarding compulsory motor insurance (the ‘Vnuk judgment’). This report also contains documentation relating to an external peer review of the work by Grant Thornton UK LLP (‘GT’).