City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectif Animation

1 MYSTERIES IN THE ARCHIVES Lesson Plan by Louise Sarrasin, educator Commission scolaire de Montréal (CSDM), Montreal, Quebec Objective To help students discover or learn more about famous or lesser-known media images that capture key events of the 20th century so they can situate the events on a timeline, better understand them and analyze certain aspects. Target audience Students age 14 to 20 Connections Arts and Culture Languages Social Sciences Films needed for the lesson plan Films in the Mysteries in the Archives collection headed by Serge Viallet (10 x 26 min) Summary of the lesson plan This lesson plan will enable students to discover or rediscover media images that capture key events in the history of the 20th century. It will help them see how the images were used by the filmmakers, journalists or the media to present this history in a certain way. In viewing films directed by Serge Viallet, Julien Gaurichon and Alexandre Auque in the Mysteries in the Archives collection, students will examine and question the footage presented so as to better understand the role that such images can play in interpreting history. In so doing, they will hone their analytical skills and critical judgment in order to develop a well-founded opinion (see Note 1). Preparatory activity: Images and facts Approximate duration: 60 min Begin by writing the following words by Serge Viallet on the board or a flipchart: “Images tell stories, and we tell the story of the images.” Get your students to comment on this quote by asking them the following questions: -

Catalogue Half Sized

Nov 2010 e u g o l a t a c & r e t t e Paul Skilleter enjoying Nigel Webb’s Mike Hawthorn Jaguar Mk1 recreation l PaulSkilleterBooks/PJPublishingLtd s 38,FarmLaneSouth BartononSea NEWMILTON w Hampshire Tel:01425612669 e e-mail:[email protected] Web:www.PaulSkilleterBooks.Co.Uk n November2010 2 ListerJaguarBookLaunch The book was launched at Race Retro, Stoneleigh, 12 -14 March 2010! When Ted Walker and I set out to record the history of Lister using Ted’s Ferret Fotographics archives as the basis, we certainly didn’t realise that what began as a relatively simple photo-book would turn into the major work that it did. But when I approached Brian Lister and told him of our intentions, he soon became personally interested in the project, and began to uncover all sorts of fascinating documents and pictures. Augmented by more period photographs from his former chief mechanic Edwin ‘Dick’ Barton, the book grew into a full- blown history of Lister, covering all Brian’s cars and telling the story of the family company, George Lister Engineering (which still flourishes today, incidentally, though it ceased to have any connection with cars after the team retired in 1959). The final cog in the mechanism, as it were, was John Pearson. As I say in the book’s introduction, John has had a longer continuous relationship with Listers than anyone else, and when I first came onto the scene around 1966, John was one of the first Jaguar racing people I met. I soon learned that for several years from 1962 he had been mechanic to John Coundley, that prolific owner and driver of Lister-Jaguars, and before that had seen the earliest Listers perform and watched Lister works driver Archie Scott Brown in his prime. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

September 2012 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kye Wankum

September 2012 www.pcaucr.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kye Wankum ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION Kye Wankum [email protected] September 2012 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emily Atkins News [email protected] Zone 1 Dates & Notes 10 First Annual Porsche Show & Swap Meet 10 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Garth Stiebel Street Survival School - Isi Papodoupulos 36 [email protected] 2012 Nominating Committee Seeking Recomendations 55 UCR TECHNICAL EDITOR Departments George O’Neill President’s Message - Mario Marrello 4 [email protected] UCR Calendar of Events 5 UCR PHOTO EDITOR UCR Socials - Isabel Starck 6 Eshel Zweig at [email protected] New Members - Angie & Mark Herring 7 Membership Anniversaries - Angie & Mark Herring 7 UCR CLUB PHOTOGRAPHER Editor’s Ramblings - Kye Wankum 8 Michael A. Coates The Way We Were - UCR Historical - John Adam 9 CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS UCR Driver Education 10 Graham Jardine Letters to the Editors 11 Ken Jensen UCR Fun Runs - David Forbes 52 Ronan McGrath The Mart 56 Andreas Trauttmansdorff Board Meeting Minutes from July 3, 2012 - Isabel Starck 59 Eshel Zweig Who’s Who In Upper Canada 61 PUBLISHER Advertiser Index 62 Richard Shepard at [email protected] Features ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATION The Targa Florio - Ronan McGrath 16 AND BILLING The 2012 PCA UCR Concours - Chris Ralphs 22 Sheri and Neil Whitlock 905-509-9692 or Email: [email protected] The ALMS Experience - Robert Moniz 28 Classic Porsche - Robert Eberschlag 40 AD & COPY DEADLINE Focus - Essential Ingredient In Driver Education - Garth Stiebel 46 30 Days prior to publication date; e.g. June 1st for the July Advertiser Of The Month: The Seidman Kaufman Group 48 issue of Provinz; July 1st for the August issue of Provinz. -

John Cooper Works Tuning MINI Cooper S Brochure

Cooper_S_GB_korr 24.02.2003 19:28 Uhr Seite 1 JOHN COOPER WORKS TUNING MINI COOPER S Cooper_S_GB_korr 24.02.2003 19:28 Uhr Seite 2 Racing in the blood From Mini Cooper to MINI Cooper S Coopers are in Britain’s blood. All over the world ‘Cooper’ means In 1959 the British public was introduced to the amazing Mini not just British automotive excellence, but personal passion and with the first Mini Cooper launched in 1961. The injection of demand for the very best. The name says far more than ‘Turbo’ John Cooper’s racing know-how created a world-beating fun, fast or ‘GTI’ ever can, standing as it does for the expertise and car that had few rivals. passion of three generations of one family. A MINI Cooper S is In 1970 Mini Cooper production came to an end. Years were that rare thing, a uniquely affordable fast, fun car with a heritage to pass before demand and enthusiastic interest led to the to be proud of. Mini Cooper revival. Fit a John Cooper Works tuning kit to your MINI Cooper S! A history of winning Formed in 1946 to design and produce the Cooper 500 Formula 3 racing car, the Cooper Car Company was an affordable way for amateurs to get into motor racing. John John Cooper – legendary F1 constructor and Mini Cooper originator. ship The Cooper Car Company became the world’s first and largest satis post-war, specialist racing car manufacturer culminating in In th winning the Formula 1 Drivers’ and Constructors’ World in America and the rear engine concept soon became the norm. -

Sir Stirling Moss 1959 Cooper T49 Monaco

! The Ex - Sir Stirling Moss, Bib Stillwell - ‘Coil Sprung’ 1959 Cooper T49 ‘Monaco’ Chassis Number: 20 • Commissioned new by Sir Stirling Moss in 1959 where he qualified the car on the front row of the grid for the 1959 British Grand Prix Sports Car Race at Aintree and went on to win at Karlskoga in Sweden and the Roskilde Ring in Denmark. • Recipient of a decorated racing history with Bib Stillwell in Australia. • Surely the ultimate ’50s Sports Racing Car with its coil sprung rear suspension and the desirable 5-speed gearbox, making it arguably more competitive than the standard Monaco. • Beautifully restored back to its 1959 specification by Simon Hadfield Motorsport and driven to a continuous string of victories, including the BRDC ‘50s Sportscar Championship and British Grand Prix support race, by then owner Frank Sytner. • Maintained with no expense spared by Pearsons Engineering throughout its current ownership and accompanied by an extensive history file, including period photographs from both Moss’ and Stilwell’s ownership, as well as more contemporary historic racing and a comprehensive collection of invoices for work both during Frank Sytner’s ownership and the current owners time. • With new FIA HTPs in the coil sprung, 5 speed format, this is your chance to get onto any of the ‘50s Sportscar grids whether it the Stirling Moss Trophy or prestigious Goodwood Revival. T. + 44 (0)1285 831 488 E. [email protected] www.williamianson.com ! To many the 1950’s is still the most evocative era of sportscar racing. Le Mans at its heyday, the Mille Miglia, names like Moss, Hawthorn, Fangio and the start of transition of power from the big manufacturers like Jaguar and Ferrari to the more bespoke race car manufacturers like Cooper and Lotus. -

Auto Racing 1 Auto Racing

Auto racing 1 Auto racing Auto racing Sebastian Vettel overtaking Mark Webber during the 2013 Malaysian Grand Prix Highest governing body FIA First contested April 28, 1887 Characteristics Mixed gender Yes Categorization Outdoor Auto racing (also known as automobile racing, car racing or motorcar racing) is a motorsport involving the racing of automobiles for competition. History The beginning of competition Motoring events began soon after the construction of the first successful gasoline-fueled automobiles. The first organized contest was on April 28, 1887, by the chief editor of Paris publication Le Vélocipède, Monsieur Fossier. It ran 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from Neuilly Bridge to the Bois de Boulogne. It was won by Georges Bouton of the De Dion-Bouton Company, in a car he had constructed with Albert, the Comte de Dion, but as he was the only competitor to show up it is rather difficult to call it a race. Another solo event occurred in 1891 when Auguste Doriot and Louis Rigoulot of Peugeot drove their gasoline-fueled Type 3 Quadricycle in the bicycle race from Paris–Brest–Paris. By the time they reached Brest, the winning cyclist Charles Terront was already back in Paris. In order to publicly prove the reliability and performance of the 'Quadricycle' Armand Peugeot had persuaded the organiser, Pierre Giffard of Le Petit Journal, to use his network of monitors and marshalls to vouchsafe and report the vehicle's performance. The intended distance of 1200 km had never been achieved by a motorised vehicle, it being about three times further than the record set by Leon Serpollet from Paris to Lyon.[1][2] Auto racing 2 Paris–Rouen: the world's first motoring contest On July 23, 1894, the Parisian magazine Le Petit Journal organized what is considered to be the world's first motoring competition from Paris to Rouen. -

23 CHENARD & 2 978 Cm³ 2 209,536 A

LE MANS RACES HISTORY___________________________________________ Distance Winner Biennial Year Manufacturer Engine cubic cap. Drivers Av. speed Fastest lap (race) Winner Triennial Cup Dép Ab Comments km Cup 1923 CHENARD & 2 978 cm³ 2 209,536 A. Lagache 92,064 F. Clément 33 3 The circuit (17,262 km) went through Pontlieue. Only the WALCKER 4 cyl. en ligne R. Léonard BENTLEY Sport Création driver could carry out repairs. « Sport » 9’39’’ - 107,328 km/h 1924 BENTLEY 2 995 cm³ 2 077,340 J. Duff 86,555 A. Lagache 41 23 The cars had to cover 20 laps with the hood up. « Sport » 4 cyl. en ligne F. Clément CHENARD & WALCKER Création 9’19’’ - 111,168 km/h 1925 LORRAINE 3 473 cm³ 2 233,982 G.de Courcelles 93,082 A. Lagache CHENARD & WALCKER CHENARD & 49 28 Race Control moved to Les Hunaudières. First American DIETRICH 6 cyl. en ligne A. Rossignol CHENARD & WALCKER R. Senéchal WALCKER participation (Chrysler). B3-6 9’10’’ A. Loqueneux R. Glaszmann 112,987 km/h M. de Zuniga Distance Winner Biennial Year Manufacturer Engine cubic cap. Drivers Av. speed Fastest lap (race) Winner Triennial Cup Dép Ab Comments km Cup 1926 LORRAINE 3 446 cm³ 2 552,414 R. Bloch 106,350 G.de Courcelles O.M. 665SS O.M. 665SS 41 24 First grandstands built and a car park for 3000 cars. The DIETRICH 6 cyl en ligne A. Rossignol LORRAINE DIETRICH Superba Superba 100 km/h average exceeded for the first time. The RN 138 B3-6 9’03’’ F. Minoia F. -

MINI and JCW Accessories Flip Catalog (2009)

YOUR MASTERPIECE AWAITS. Keep it wild. Mini Motoring Accessories john cooper works accessories MINI Hardtop 2007 – Present MINI Clubman 2008 – Present MINI convertible 2009 – Present Let’s face it. You’re different. It’s one of the reasons you found yourself behind the wheel of a MINI in the first place. But it SOMEDAY, ART HISTORIANS WILL REFER TO doesn’t stop there, the worlds of Design, Luggage and Leisure, and Music, Communications and Technology await. With the help of original MINI Motoring Accessories, you can transform your already-unique MINI Hardtop, MINI Convertible or THIS AS THE ZIG-ZAG-ZUGGIST MOVEMENT. MINI Clubman into a one-of-a-kind work of whiptastic art. So open your mind and toss out any preconceived notions. Your MINI is ready. Race through these pages then flip for an even faster ride with John Cooper Works Performance Accessories. So what are you waiting for? Go ahead and create your masterpiece. GET READY TO CREATE: Exterior & interior design Luggage & leisure Music, Communications A “MINI” Guide to using this catalog & technology Wheels 3 – 7 Roof Rack Systems 25 – 26 Portable Navigation System 35 Mobility Kit 7 Rear Rack Systems 27 Map Update, On-Board Navigation System 35 GUIDE Mudflaps 7 Nose Masks 28 Alarm System 35 Winter Tire Packages 7 Sunshades 28 Snap-In Adaptors 35 Electronic Tire Pressure Gauge 8 Invisishield Film 28 CD Changer, Multi Disk 36 Wheel Locks 8 Mud Flaps 28 SIRIUS Satellite Radio 36 Snow Chains 8 Magnetic Stone Guards 28 iPod® Interface 36 Traction Aid 8 Bumper Strips 28 PLANNER Tire Totes -

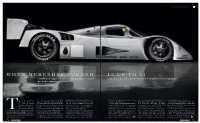

W H E N M E R C E D E S T U R N E D I T U P T O

SAUBER-MERCEDE S C 1 1 When Mercedes turned it up to 1 1 Twenty years ago the marque teamed up with Sauber to produce the C11 – a car that ruled all and influenced a return to F1 BY GARY WATKIN S he first pure-bred The C11 was the fruit of an unlikely with Mauro Baldi and Jean-Louis Schlesser. One Pointed Star was soon back at the pinnacle of the engines, it was natural that he should look to say, they didn’t take a lot of convincing.” Mercedes-Benz racer for relationship. A back-door deal to supply engines of the five drivers to notch up victories in the sport as an engine supplier. Mercedes’ road-car range for a replacement. The official line was that the engine was 35 years. A World to the Swiss Sauber sports car squad in the mid- C11 was a young Schumacher, who’d been The tiny Sauber team from Hinwil had made He reckoned the 5-litre M117, in lightly developed for racing by renowned Swiss tuner Championship winner. 1980s paved the way for Mercedes to return plucked from Formula 3 to become part of a contact with Mercedes in 1981. A young road turbocharged form, would be the ideal Heine Mader. But Welti explains that this The car that gave us officially to motor sport in ’88. For 1990, the junior programme conceived by new Mercedes car suspension engineer by the name of Leo Ress powerplant for the Group C fuel formula. arrangement was a smokescreen. Michael Schumacher. The partnership produced the first bespoke Mercedes motor sport boss Jochen Neerpasch. -

CFD-Analysis of the Aerodynamic Prop- Erties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR

CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic prop- erties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR Bachelor’s thesis in Applied Mechanics ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 Bachelor thesis nr 2015:07 Bachelor’s project TMEX02-15-15 CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic properties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR Comparison of drag- and lift forces generated when the Mercedes’ air brake is deployed ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 CFD-analysis of the aerodynamic properties of a Mercedes-Benz 300SLR. Comparison of drag- and lift forces generated when the Mercedes’ air brake is de- ployed. ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER © ANDREAS FALKOVÉN JOHAN NORDIN KRESHNIK RAMA ANDREAS RASK PHILIP SJÖSTRAND MICHAEL STADLER, 2015. Supervisor: Emil Ljungskog Examiner: Professor Lennart Löfdahl Bachelor’s project TMEX02-15-15 Department of Applied Mechanics Division of Vehicle Engineering and Autonomous Systems Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Telephone +46 31 772 1000 Cover: Streamlines around the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR travelling at 120 kph. Gothenburg, Sweden 2015 iv Abstract Mercedes-Benz was one of the most prominent car manufacturers in motorsport in the 50’s. In 1955 they participated with the model 300 SLR in the Le Mans 24- hour race. What made this model standing out was the mounted air brake, which would compensate for the weaker drum brakes compared with competing models’ disc brakes. -

Mercedes-Benz 300SL

Mercedes-Benz 300SL From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Mercedes-Benz 300SL Manufacturer Mercedes-Benz Also called Mercedes Benz 300 SLR 2-door coupe Production 1952-1963 Predecessor none Successor Mercedes-Benz 230SL Body style 2 door coupé, roadster Engine Mercedes 2995cc, SOHC Transmission 4-speed MANUAL Wheelbase 94.5 in Length 178 in Width 70.5 in Height 51.1 in Curb weight 2351 lbs The Mercedes-Benz 300SL is a two-seat, closed sports car with characteristic gull-wing doors, and later, offered as an open roadster. Built by Daimler-Benz AG and internally numbered W198, the road version of 1952 was based (somewhat loosely) on the company's highly successful competition-only sports car of 1950, the Mercedes-Benz 300SL (W194) which had less power, as it still had carburetors. This model was suggested by Max Hoffman. Because it was intended for customers whose preferences were reported to Hoffman by dealers he supplied in the booming, post-war American market, it was introduced at the 1954 New York Auto Show—unlike previous models introduced at either the Frankfurt or Geneva shows. The 300SL was best known for both its distinctive gullwing or butterfly wing doors and for being the first-ever gasoline-powered car equipped with fuel injection directly into the combustion chamber. The gullwing version was available from March 1955 to 1957. In Mercedes-Benz fashion, the "300" referred to the engine's cylinder displacement, in this case, three liters. The "SL", as applied to a roadster, stood for "Sport Leicht" or "Sport Light." More widely produced (25,881 units) and starting in 1954 was the similar looking 190SL with a 105hp 4cyl engine, available only as roadster (or with an additional hardtop, as Coupe Roadster).