The Fourth Reich: the Specter of Nazism from World War II to the Present'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5. Between Gleichschaltung and Revolution

Chapter 5 BETWEEN GLEICHSCHALTUNG AND REVOLUTION In the summer of 1935, as part of the Germany-wide “Reich Athletic Com- petition,” citizens in the state of Schleswig-Holstein witnessed the following spectacle: On the fi rst Sunday of August propaganda performances and maneuvers took place in a number of cities. Th ey are supposed to reawaken the old mood of the “time of struggle.” In Kiel, SA men drove through the streets in trucks bearing … inscriptions against the Jews … and the Reaction. One [truck] carried a straw puppet hanging on a gallows, accompanied by a placard with the motto: “Th e gallows for Jews and the Reaction, wherever you hide we’ll soon fi nd you.”607 Other trucks bore slogans such as “Whether black or red, death to all enemies,” and “We are fi ghting against Jewry and Rome.”608 Bizarre tableau were enacted in the streets of towns around Germany. “In Schmiedeberg (in Silesia),” reported informants of the Social Democratic exile organization, the Sopade, “something completely out of the ordinary was presented on Sunday, 18 August.” A no- tice appeared in the town paper a week earlier with the announcement: “Reich competition of the SA. On Sunday at 11 a.m. in front of the Rathaus, Sturm 4 R 48 Schmiedeberg passes judgment on a criminal against the state.” On the appointed day, a large crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Th e Sopade agent gave the setup: “A Nazi newspaper seller has been attacked by a Marxist mob. In the ensuing melee, the Marxists set up a barricade. -

Intentions of Right-Wing Extremists in Germany

IOWA STATE UNIVERSITY Intentions of Right-wing Extremists in Germany Weiss, Alex 5/7/2011 Since the fall of the Nazi regime, Germany has undergone extreme changes socially, economically, and politically. Almost immediately after the Second World War, it became illegal, or at least socially unacceptable, for Germans to promote the Nazi party or any of its ideologies. A strong international presence from the allies effectively suppressed the patriotic and nationalistic views formerly present in Germany after the allied occupation. The suppression of such beliefs has not eradicated them from contemporary Germany, and increasing numbers of primarily young males now identify themselves as neo-Nazis (1). This group of neo-Nazis hold many of the same beliefs as the Nazi party from the 1930’s and 40’s, which some may argue is a cause for concern. This essay will identify the intentions of right-wing extremists in contemporary Germany, and address how they might fit into Germany’s future. In order to fully analyze the intentions of right-wing extremists today, it is critical to know where and how these beliefs came about. Many of the practices and ideologies of the former Nazi party are held today amongst contemporary extreme-right groups, often referred to as Neo-Nazis. A few of the behaviors of the Neo-Nazis that have been preserved from the former Nazi party are anti-Semitism, xenophobia and violence towards “non-Germans”, and ultra- conservatism (1). The spectrum of the right varies greatly from primarily young, uneducated, violent extremists who ruthlessly attack members of minority groups in Germany to intellectuals and journalists that are members of the New Right with influence in conservative politics. -

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

Austria's Failed Denazification

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2020 The Silent Reich: Austria’s Failed Denazification Henry F. Goodson Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Goodson, Henry F., "The Silent Reich: Austria’s Failed Denazification" (2020). Student Publications. 839. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/839 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Silent Reich: Austria’s Failed Denazification Abstract Between 1945 and 1956, the Second Austrian Republic failed to address the large number of former Austrian Nazis. Due to Cold War tensions, the United States, Britain, and France helped to downplay Austria’s cooperation with the Nazi Reich in order to secure the state against the Soviets. In an effort to stall the spread of socialism, former fascists were even recruited by Western intelligence services to help inform on the activities of socialists and communists within Austria. Furthermore, the Austrian people were a deeply conservative society, which often supported many of the far-right’s positions, as can be seen throughout contemporary Austrian newspaper articles and editorials. Antisemitism, belief in the superiority of Austro-Germanic culture, disdain for immigrants, and desire for national sovereignty were all widely present in Austrian society before, during, and after the Nazi period. These cultural beliefs, combined with neglect from the Western powers, integrated the far-right into the political decision-making process. -

La Dialectique Néo-Fasciste, De L'entre-Deux-Guerres À L'entre-Soi

La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi. Nicolas Lebourg To cite this version: Nicolas Lebourg. La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi.. Vocabulaire du Politique : Fascisme, néo-fascisme, Cahiers pour l’Analyse concrète, Inclinaison-Centre de Sociologie Historique, 2006, pp.39-57. halshs-00103208 HAL Id: halshs-00103208 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00103208 Submitted on 3 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi. Le siècle des nations s’achève en 1914. La Première Guerre mondiale produit d’une part une volonté de dépassement des antagonismes nationalistes, qui s’exprime par la création de la Société des Nations ou le vœu de construction européenne, d’autre part une réaction ultra-nationaliste. Au sein des fascismes se crée, en chaque pays, un courant marginal européiste et sinistriste1. Dans les discours de Mussolini, l’ultra-nationalisme impérialiste cohabite avec l’appel à l’union des « nations prolétaires » contre « l’impérialisme » et le « colonialisme » de « l’Occident ploutocratique » – un discours qui, après la naissance du Tiers-monde, paraît généralement relever de l’extrémisme de gauche. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Persistence and Activation of Right-Wing Political Ideology

Persistence and Activation of Right-Wing Political Ideology Davide Cantoni Felix Hagemeister Mark Westcott* May 2020 Abstract We argue that persistence of right-wing ideology can explain the recent rise of populism. Shifts in the supply of party platforms interact with an existing demand, giving rise to hitherto in- visible patterns of persistence. The emergence of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) offered German voters a populist right-wing option with little social stigma attached. We show that municipalities that expressed strong support for the Nazi party in 1933 are more likely to vote for the AfD. These dynamics are not generated by a concurrent rightward shift in political attitudes, nor by other factors or shocks commonly associated with right-wing populism. Keywords: Persistence, Culture, Right-wing ideology, Germany JEL Classification: D72, N44, P16 *Cantoni: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munich, CEPR, and CESifo. Email: [email protected]. Hagemeister: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munich. Email: [email protected]. Westcott: Vivid Economics, Lon- don. Email: [email protected]. We would like to thank Leonardo Bursztyn, Vicky Fouka, Mathias Buhler,¨ Joan Monras, Nathan Nunn, Andreas Steinmayr, Joachim Voth, Fabian Waldinger, Noam Yuchtman, Ekaterina Zhuravskaya and seminar participants in Berkeley (Haas), CERGE-EI, CEU, Copenhagen, Dusseldorf,¨ EUI, Geneva, Hebrew, IDC Herzliya, Lund, Munich (LMU), Nuremberg, Paris (PSE and Sciences Po), Passau, Pompeu Fabra, Stock- holm (SU), Trinity College Dublin, and Uppsala for helpful comments. We thank Florian Caro, Louis-Jonas Hei- zlsperger, Moritz Leitner, Lenny Rosen and Ann-Christin Schwegmann for excellent research assistance. Edyta Bogucka provided outstanding GIS assistance. Financial support from the Munich Graduate School of Economics and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through CRC-TRR 190 is gratefully acknowledged. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

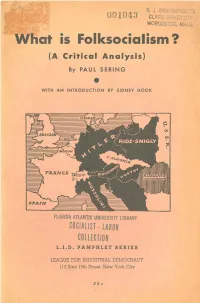

What Is Folksocialism? (A Critical Analysis)

001043 What is Folksocialism? (A Critical Analysis) By PAUL SERING • WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIDNEY HOOK . f' SPAIN flORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SOCIALIST· LABOR COLLECTION L.LD. PAMPHLET SERIES LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street, New York City 25c I HE LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY is a membership society en· T gaged in education toward a social order based on production for use and not for profit. To this end the League conducts research, lecture and information services, suggests practical plans for increasing social con· trol, organizes city chapters, publishes books and pamphlets on problems of industrial democracy, and sponsors conferences, forums, luncheon dis cussions and radio talks in leading cities where it has chapters. r-------.lTs OFFICERS FOR 1936-1937 ARE:--------, PRESIDENT ROBERT MORSS LOVETT VICE-PRESIDENTS JOHN DEWEY ALEXANDER MEIKLEJOHN JOHN HAYNES HOLMES MARY R. SANFORD JAMES H. MAURER VIDA D. SCUDDER FRANCIS J. McCONNELL HELEN PHELPS STOKES TB.EASUJlEB STUART CHASE • EXECUTIYE DIBECTORS NORMAN THOMAS HARRY W. LAIDLER EXJ:Cl7TIVB UCBIITAIlY ORGANIZATION SIlCIIETABY MARY FOX MARY W. HILLYER • ..hrinant SecretaTJI Chapter Secretariu CHARLES ENOVALL BERNARD KIRBY. Chlcago SIDNEY SCHULMAN. Phlla. ETHAN EDLOFF. Detroit Emerge1lCV Committee for Striker" Relief ROBERT O. MENAKER 000 LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street New York City, N. Y. COPYRIGHT 1937 by the LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL......... DEMOCRACY WHAT IS FOLKsOCIALlsM? (A Critical Analysis) BY PAUL SERING WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIDNEY HOOK • TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY HARRIET YOUNG AND MARY Fox • Published by LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street, New York City February, 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION " 7 WHAT Is FOLKSOCIALISM? (A Critical Analysis) ~ 12 I. -

Government Commits to Seeking a Ban of the Extreme Right-Wing National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD)

Government Commits to Seeking a Ban of the Extreme Right-Wing National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD). Suggested Citation: Government Commits to Seeking a Ban of the Extreme Right-Wing National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD)., 1 German Law Journal (2000), available at http://www.germanlawjournal.com/index.php?pageID=11&artID=6 [1] Through the Federal Minister of the Interior, Otto Schily, and Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder (both Social Democratic Party - “SPD”), the Federal Government has clearly expressed its intent to move ahead with a motion before the Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) seeking a ban of the extreme right-wing National Democratic Party of Germany (“NPD”). The Government’s insistence comes in spite of mere acquiescence on the issue from its coalition partner the Bündnis 90/GRÜNEN (Alliance 90/The Greens). It seemed as if Interior Minister Schily would be able to summon the support of a majority of the State Interior Ministers making it possible for a coalition of entities to bring the motion (including both Parliamentary Chambers, the executive branch of Government as well as a majority of the individual states) and thus thinly spreading the political risks associated with the move. The CDU (Christian Democratic Union) fraction in the Bundestag has recently announced, however, that it will oppose any efforts to submit a motion seeking a ban on the NPD and several States have announced their intention not to participate in the motion, leaving Interior Minister Schily in an awkward alliance with Bavarian (State) Interior Minister Günther Beckstein while prominent Social Democrats at the state level and Greens at the federal level continue to express reservations about the necessity for, the likely success of, and the ultimate effectiveness of a motion seeking a ban. -

The Kpd and the Nsdap: a Sttjdy of the Relationship Between Political Extremes in Weimar Germany, 1923-1933 by Davis William

THE KPD AND THE NSDAP: A STTJDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLITICAL EXTREMES IN WEIMAR GERMANY, 1923-1933 BY DAVIS WILLIAM DAYCOCK A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1980 1 ABSTRACT The German Communist Party's response to the rise of the Nazis was conditioned by its complicated political environment which included the influence of Soviet foreign policy requirements, the party's Marxist-Leninist outlook, its organizational structure and the democratic society of Weimar. Relying on the Communist press and theoretical journals, documentary collections drawn from several German archives, as well as interview material, and Nazi, Communist opposition and Social Democratic sources, this study traces the development of the KPD's tactical orientation towards the Nazis for the period 1923-1933. In so doing it complements the existing literature both by its extension of the chronological scope of enquiry and by its attention to the tactical requirements of the relationship as viewed from the perspective of the KPD. It concludes that for the whole of the period, KPD tactics were ambiguous and reflected the tensions between the various competing factors which shaped the party's policies. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I THE CONSTRAINTS ON CONFLICT 24 CHAPTER II 1923: THE FORMATIVE YEAR 67 CHAPTER III VARIATIONS ON THE SCHLAGETER THEME: THE CONTINUITIES IN COMMUNIST POLICY 1924-1928 124 CHAPTER IV COMMUNIST TACTICS AND THE NAZI ADVANCE, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW THREATS 166 CHAPTER V COMMUNIST TACTICS, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW OPPORTUNITIES 223 CHAPTER VI FLUCTUATIONS IN COMMUNIST TACTICS DURING 1932: DOUBTS IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR 273 CONCLUSIONS 307 APPENDIX I VOTING ALIGNMENTS IN THE REICHSTAG 1924-1932 333 APPENDIX II INTERVIEWS 335 BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 4 ABBREVIATIONS 1. -

Robert O. Paxton-The Anatomy of Fascism -Knopf

Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page b also by robert o. paxton French Peasant Fascism Europe in the Twentieth Century Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 Parades and Politics at Vichy Vichy France and the Jews (with Michael R. Marrus) Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page i THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page ii Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iii THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM ROBERT O. PAXTON Alfred A. Knopf New York 2004 Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iv this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf Copyright © 2004 by Robert O. Paxton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. isbn: 1-4000-4094-9 lc: 2004100489 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page v To Sarah Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vi Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vii contents Preface xi chapter 1 Introduction 3 The Invention of Fascism 3 Images of Fascism 9 Strategies 15 Where Do We Go from Here? 20 chapter 2 Creating Fascist Movements 24 The Immediate Background 28 Intellectual, Cultural, and Emotional