Avant-Garde Women and Ambition by Ruth Hemus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20Th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography A Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum Brings Together Iconic Masterpieces and Unknown Avant-garde Artists from the Israel Museum’s Collections On view at Israel Museum July 16, 2019 – January 5, 2020 Jerusalem, Israel, August 1, 2019 – Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum delves into the work of photographers who shaped and defined photography between 1900-1945, helping to expand public understanding of early modern photography through a presentation that brings together acclaimed and unknown works by male and female artists. Featuring around 200 works from seminal artists such as Alfred Stieglitz, August Sander, Edward Weston, and Man Ray, alongside lesser-known photographers such as Liselotte Grschebina, ringl+pit, Laure Albin Guillot, and Frieda Meyer Jakobson, the exhibition fosters a deeper level of understanding around the development of cultural production at the time and uncovers unexpected and surprising discoveries, including a personal note written by Alfred Stieglitz on the back of the 1916 print Portrait of Marie Rapp. The exhibition also fosters contemporary relevancy around the works, connecting camera techniques by Modern photographers to current images captured by cell phones. “Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum showcases the Museum’s incredible photography collection and demonstrates its continued commitment to supporting the exploration and exhibition of images through robust programming and curatorial expertise,” said Ido Bruno, Anne and Jerome Fisher Director of the Israel Museum. “I am thrilled that our visitors will have the opportunity to experience this unique selection of iconic Modern photographs drawn from the Museum’s extensive holdings, many which are going on display for the first time.” Drawing on a recent gift from collector Gary B. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021

GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF Member of the group “Cercle et Carré”, Marcelle Cahn's works from the very first period of her production are linked to expressionism thanks to her expressionist master Lovis Corinth in Berlin, then to cubism by joining the courses of the Modern Academy in the studio of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant in Paris where she did not go beyond abstraction, proposing a personal style combining geometric rigor and sensitivity; finally she joined purism and constructivism. After the War, she regularly participates in the “Salon des Réalités Nouvelles”, where she shows her abstract compositions. It is at this time that she will define the style that characterizes her paintings with white backgrounds crossed by a play of lines or forms in relief, it is also at this time that she realizes her astonishing collages created from everyday supports: envelopes, labels, photographs, postcards, stickers. Marcelle Cahn (at the center) surrounded by the members of the group “Cercle et Carré” (photograph taken in 1929) : Francisca Clausen, Florence Henri, Manolita Piña de Torres García, Joaquín Torres García, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, Pierre Daura, Sophie Tauber-Arp, Michel Seuphor, Friedrich Vordemberge Gildewart, VeraIdelson, Luigi Russolo, Nina Kandinsky, Georges Vantongerloo, Vassily Kandinsky and Jean Gorin. 2 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF BIOGRAPHY Born March 1st 1895 at Strasbourg, died September 21st 1981 at Neuilly-sur-Seine 1915-1920 From 1915 to 1919, she lives in Berlin, where she was a student of Lovis Corinth. Her first visit to Paris came in 1920 where she also tries her hand at small geometrical drawings. -

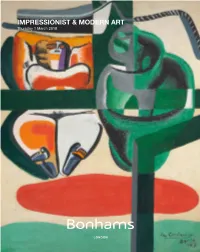

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893-1965) By

The Social, Political and Economic Determinants of a Modern Portrait Artist: Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893-1965) by MARIE CONSIDINE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham April 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT As the first major study of the portrait artist Bernard Fleetwood-Walker (1893- 1965), this thesis locates the artist in his social, political and economic context, arguing that his portraiture can be seen as an exemplar of modernity. The portraits are shown to be responses to modern life, revealed not in formally avant- garde depictions, but in the subject-matter. Industrial growth, the increasing population, expanding suburbs, and a renewed interest in the outdoor life and popular entertainment are reflected in Fleetwood-Walker’s artistic output. The role played by exhibition culture in the creation of the portraits is analysed: developing retail theory affected gallery design and exhibition layout and in turn impacted on the size, subject matter and style of Fleetwood-Walker’s portraits. -

Catalogue-Surréalisme.Pdf

Surréalisme librairie patrick fréchet LIBRAIRIE SOLSTICES / SOLSTICES RARE BOOKS 16, RuE PESTALOZZI F-75005 PARIS +33 (0)613 801 945 [email protected] www.librairie-solstices.com RCS LILLE 424 568 665 membre du / Member of Syndicat de la Librairie Ancienne et moderne (SLAm) & de la Ligue Internationale de la Librairie Ancienne / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (LILA / ILAB) vENTE PAR CORRESPONDANCE Ou SuR RENDEZ -vOuS LIBRAIRIE PATRICK FRÉCHET LE PRADEL F-12270 SAINT-ANDRÉ DE NAJAC +33 (0)6 87 09 31 64 [email protected] RCS RODEZ 443 665 229 vENTE PAR CORRESPONDANCE uNIquEmENT Illustrations de couverture : no 43 & 30 1 / Guillaume APOLLInAIRE , Prsy Tiresiovy [Les Mamelles de Tiresias ] Nadrealistické drama o dvou jednanich s prologem Prague, Odeon, octobre 1926 20 x 14 cm, 75 p., 4 illustrations de Joseph SImA , broché, couverture couleurs. Tirage limité à 1000 ex. numérotés (celui-ci le n° 220) de la traduction en tchèque par Jaroslav Seifert. Typographie et maquette de couverture de Karel TEIGE . Édition originale tchèque 200 € 2 / Bifur, Revue paraissant 6 fois par an Paris, Éditions du Carrefour, sans date [1930] 1 feuillet double, 18 x 11 cm imprimé en noir recto verso sur papier blanc Prospectus publié à l’occasion de la parution du n° 4 de la revue Bifur , de Hebdomeros par Giorgio de Chirico et de Frontières humaines par Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. Édition originale 75 € 3 / Salvador DALI , La Femme visible Paris, Éditions Surréalistes, 1930 1 feuillet, 21 x 15 cm imprimé en noir recto verso sur papier blanc illustré au recto de la photo des yeux de Gala Table des matières et des illustrations et justification du tirage au verso. -

Find Book # on the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain

EDVPNKOYORFZ // Doc > On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain On th e Th irteenth Stroke of Midnigh t: Surrealist Poetry in Britain Filesize: 7.63 MB Reviews A must buy book if you need to adding benefit. We have study and so i am sure that i am going to likely to study once again again in the foreseeable future. I realized this book from my i and dad encouraged this ebook to discover. (Duane Fadel) DISCLAIMER | DMCA ISTVDZEZULX3 « Book ~ On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight: Surrealist Poetry in Britain ON THE THIRTEENTH STROKE OF MIDNIGHT: SURREALIST POETRY IN BRITAIN Carcanet Press Ltd, United Kingdom, 2013. Undefined. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. This book, the first published anthology of British surrealist poetry, takes its title from Herbert Read s words when he opened the Surrealist Poems and Objects exhibition at the London Gallery at midnight on 24 November 1937. Within a few years the Second World War would eectively fragment the British surrealist movement, dispersing its key members and leaving the surrealist flame flickering only in isolated moments and places. Yet British surrealist writing was vibrant and, at its best, durable, and now takes its place in the wider European context of literary surrealism. On the Thirteenth Stroke of Midnight includes work by Emmy Bridgwater, Jacques B. Brunius, Ithell Colquhoun, Hugh Sykes Davies, Toni del Renzio, Anthony Earnshaw, David Gascoyne, Humphrey Jennings, Sheila Legge, Len Lye, Conroy Maddox, Reuben Medniko, George Melly, E.L.T. Mesens, Desmond Morris, Grace Pailthorpe, Roland Penrose, Edith Rimmington, Roger Roughton, Simon Watson Taylor and John W. -

Surrealism and Psychoanalysis in the Work of Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff

Surrealism and Psychoanalysis in the work of Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff: 1935-1940 Lee Ann Montanaro Ph.D. History of Art The University of Edinburgh 2010 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. ABSTRACT The story of the collaboration between the psychoanalyst Dr Grace Pailthorpe and the artist Reuben Mednikoff is indeed an extraordinary one. The aim of this thesis is to throw light upon their joint research project between 1935, when they first met, and 1940, when they were expelled from the British Surrealist group with which they had been closely involved since its official launch in 1936. The project that Pailthorpe and Mednikoff plunged into just days after they first met in February 1935 focused on how art could be used as a way of curing mental problems. Paintings and drawings produced ‘automatically’ were used as a means to bring memories to a conscious level. Many personal tensions, obsessions and fears that had lain dormant and repressed were released and detailed commentaries and explanations followed every work they produced in order for the exercise to be fully therapeutic. The aim was to externalise the unconscious and reintegrate it with the conscious. Despite the fact that Pailthorpe’s work was hailed as ‘the best and most truly Surrealist’ by the leader of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, at the 1936 International Surrealist exhibition in London, which brought the movement to Britain, the couple were expelled from the British Surrealist group just four years later and moved to America into relative obscurity. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 19 (Winter, 1981), pp. 3-34 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778652 . Accessed: 08/09/2013 11:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.147.202.25 on Sun, 8 Sep 2013 11:08:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism* ROSALIND KRAUSS I open my subject with a comparison. On the one hand, thereis Man Ray's Monument to de Sade, a photograph made in 1933 for the magazine Le Surreal- isme au servicede la rekvolution.On the other,there is a self-portraitby Florence Henri, given wide exposure by its appearance in the 1929 Foto-Auge,a publica- tion thatcatalogued theEuropean avant-garde'sposition withregard to photogra- phy.' This comparison involves, then, a slight adulteration of my subject- surrealism-by introducingan image deeply associated with the Bauhaus. For FlorenceHenri had been a studentof Moholy-Nagy,although at the timeof Foto- Auge she had returnedto Paris. -

Sonia Delaunay

6. Bruce Altshuler, “Instructions for a World in post-WWII Japan, see Midori articles in the volume: Donald Richie, of Stickiness: The Early Conceptual Work Yamamura, Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the “Stumbling Front Line: Yoko Ono’s Avant- of Yoko Ono,” in Munroe, Yes: Yoko Ono, Singular (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, Garde Show,” and Toshi Ichiyanagi, “Voice 65. Altshuler cites an e-mail to him from 2015), 9–44. of the Most Avant-Garde: Objection to Ono, November 3, 1999. 8. Aside from her informative text, Donald Richie” (122–25). 7. For more on the anti-conformist tendency Yoshimoto translated two important Sonia Delaunay Delaunay’s international stature are er just as many of my (baby boomer) Edited by Anne Montfort, with contribu- these primary materials along with generation experienced this same tions by Jean-Claude Marcadé et al. others at institutions in France, requirement without necessarily self- Paris Museés & Tate Enterprises, 2014 Germany, United States, Russia, identifying as androgynous. 4 Portugal, and Spain. Brigitte Leal discusses the important Reviewed by Jan Garden Castro The first essays, “In St. Petersburg” ‘Fauve’ works the artist created after her by Jean-Claude Marcadé and “Being studies with Ludwig Schmid-Reutte in he Tate Modern catalogue and Russian in Paris” by Sherry Buck- Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1904, her studies exhibition is a visual tour de berrough, touch on Sergei Diaghilev’s with Rudolf Grossmann in Paris in 1907, Tforce, with over 250 mostly full- Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) magazine as and her introduction to the art of Braque, color illustrations that highlight Sonia an important part of the young artist’s Picasso, Derain, Dufy, Metzinger, Pascin, Delaunay’s artistic range working in formative influences, and on the and her future husband, Robert diverse media, materials, and processes Ukrainian and Russian needlework and Delaunay (they married in 1910). -

Female Photographers' Self-Portraits in Berlin 1929-1933

SELF-EXPRESSION AND PROFESSION: FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS’ SELF-PORTRAITS IN BERLIN 1929-1933 By Sophie Rycroft A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham as part of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in History of Art. Department of History of Art School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2013 Student ID Number: 0944443 History of Art MPhil (B) Word Count: 19,998 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is the first in-depth study of female photographers’ images of themselves, with their cameras, working in Weimar Berlin. A focus on three self-portraits by women at the heart of the so-called ‘New Photography’, will allow insight into the importance of the self- portrait genre for female photographers, who sought to establish themselves in this rapidly developing field. The photographers Lotte Jacobi (1896-1990), Eva Besnyö (1910-2003) and Marianne Breslauer (1909-2001) have diverse photographic oeuvres yet each produced an occupational self-portrait whilst in Berlin between 1929 and 1933.