Mechanics and Expression: Franz Roh and the New Vision — a Historical Sketch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Culture

HISTORY AND CULTURE A HAMBURG PORTUGUESE IN THE SERVICE OF THE HAGANAH: THE TRIAL AGAINST DAVID SEALTIEL IN HAMBURG (1937) Ina Lorenz (Hamburg. Germany) Spotlighted in the story here to be told is David de Benjamin Sealtiel (Shaltiel, 1903–1969), a Sephardi Jew from Hamburg, who from 1934 worked for the Haganah in Palestine as a weapons buyer. He paid for that activity with 862 days in incarceration under extremely difficult conditions of detention in the concentration camps of the SS.1 Jewish Immigration into Palestine and the Founding of the Haganah2 In order to be able to effectively protect the new Jewish settlements in Palestine from Arab attacks, and since possession of weapons was prohibited under the British Mandatory administration, arms and munitions initially were generally being smuggled into Palestine via French- controlled Syria. The leaders of the Haganah and Histadrut transformed the Haganah with the help of the Jewish Agency from a more or less untrained militia into a paramilitary group. The organization, led by Yisrael Galili (1911–1986), which in the rapidly growing Jewish towns had approximately 10,000 members, continued to be subordinate to the civilian leadership of the Histadrut. The Histadrut also was responsible for the ———— 1 Michael Studemund-Halévy has dealt with the fascinating, complex personality of David Sealtiel/Shaltiel in a number of publications in German, Hebrew, French and English: “From Hamburg to Paris”; “Vom Shaliach in den Yishuv”; “Sioniste au par- fum romanesque”; “David Shaltiel.” See also [Shaltiel, David]. “In meines Vaters Haus”; Scholem. “Erinnerungen an David Shaltiel (1903–1968).” The short bio- graphical sketches on David Sealtiel are often based on inadequate, incorrect, wrong or fictitious informations: Avidar-Tschernovitz. -

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20Th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography A Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum Brings Together Iconic Masterpieces and Unknown Avant-garde Artists from the Israel Museum’s Collections On view at Israel Museum July 16, 2019 – January 5, 2020 Jerusalem, Israel, August 1, 2019 – Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum delves into the work of photographers who shaped and defined photography between 1900-1945, helping to expand public understanding of early modern photography through a presentation that brings together acclaimed and unknown works by male and female artists. Featuring around 200 works from seminal artists such as Alfred Stieglitz, August Sander, Edward Weston, and Man Ray, alongside lesser-known photographers such as Liselotte Grschebina, ringl+pit, Laure Albin Guillot, and Frieda Meyer Jakobson, the exhibition fosters a deeper level of understanding around the development of cultural production at the time and uncovers unexpected and surprising discoveries, including a personal note written by Alfred Stieglitz on the back of the 1916 print Portrait of Marie Rapp. The exhibition also fosters contemporary relevancy around the works, connecting camera techniques by Modern photographers to current images captured by cell phones. “Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum showcases the Museum’s incredible photography collection and demonstrates its continued commitment to supporting the exploration and exhibition of images through robust programming and curatorial expertise,” said Ido Bruno, Anne and Jerome Fisher Director of the Israel Museum. “I am thrilled that our visitors will have the opportunity to experience this unique selection of iconic Modern photographs drawn from the Museum’s extensive holdings, many which are going on display for the first time.” Drawing on a recent gift from collector Gary B. -

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By Julia Silvia Feldhaus A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in German Written under the direction of Martha B. Helfer And Michael G. Levine And approved by ____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By JULIA SILVIA FELDHAUS Dissertation Directors: Martha B. Helfer Michael G. Levine This dissertation investigates the conflict between the powerful emancipatory image of the New Woman as represented in the illustrated magazines of the Weimar Republic and the translation of this image into a lifestyle acted out by women during this era. I argue that while female journalists promote the image of the New Woman in illustrated magazines as a liberating opening onto self-determination and self- management, this very image is simultaneously and paradoxically oppressive. For women to shake off the inheritance of a patriarchal past, they must learn to adjust to a new identity, one that is still to a large extent influenced by and in the service of men. The ideal beauty image designed by female journalists as a framework for emancipation in actuality turned into an oppressive normalization in professional and social markets in which traditional rules no longer obtained. -

MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021

GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF Member of the group “Cercle et Carré”, Marcelle Cahn's works from the very first period of her production are linked to expressionism thanks to her expressionist master Lovis Corinth in Berlin, then to cubism by joining the courses of the Modern Academy in the studio of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant in Paris where she did not go beyond abstraction, proposing a personal style combining geometric rigor and sensitivity; finally she joined purism and constructivism. After the War, she regularly participates in the “Salon des Réalités Nouvelles”, where she shows her abstract compositions. It is at this time that she will define the style that characterizes her paintings with white backgrounds crossed by a play of lines or forms in relief, it is also at this time that she realizes her astonishing collages created from everyday supports: envelopes, labels, photographs, postcards, stickers. Marcelle Cahn (at the center) surrounded by the members of the group “Cercle et Carré” (photograph taken in 1929) : Francisca Clausen, Florence Henri, Manolita Piña de Torres García, Joaquín Torres García, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, Pierre Daura, Sophie Tauber-Arp, Michel Seuphor, Friedrich Vordemberge Gildewart, VeraIdelson, Luigi Russolo, Nina Kandinsky, Georges Vantongerloo, Vassily Kandinsky and Jean Gorin. 2 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF BIOGRAPHY Born March 1st 1895 at Strasbourg, died September 21st 1981 at Neuilly-sur-Seine 1915-1920 From 1915 to 1919, she lives in Berlin, where she was a student of Lovis Corinth. Her first visit to Paris came in 1920 where she also tries her hand at small geometrical drawings. -

Alternative Perspectives of African American Culture and Representation in the Works of Ishmael Reed

ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of Zo\% The requirements for IMl The Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Jason Andrew Jackl San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Jason Andrew Jackl 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Alternative Perspectives o f African American Culture and Representation in the Works o f Ishmael Reed by Jason Andrew Jackl, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Grec/C Ph.D. Professor of English Sarita Cannon, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED Jason Andrew JackI San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis demonstrates the ways in which Ishmael Reed proposes incisive countemarratives to the hegemonic master narratives that perpetuate degrading misportrayals of Afro American culture in the historical record and mainstream news and entertainment media of the United States. Many critics and readers have responded reductively to Reed’s work by hastily dismissing his proposals, thereby disallowing thoughtful critical engagement with Reed’s views as put forth in his fiction and non fiction writing. The study that follows asserts that Reed’s corpus deserves more thoughtful critical and public recognition than it has received thus far. To that end, I argue that a critical re-exploration of his fiction and non-fiction writing would yield profound contributions to the ongoing national dialogue on race relations in America. -

Tate Papers - Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching

Tate Papers - Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/07spring/saletni... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching Jeffrey Saletnik Fig.1 Eva Hesse No Title , 1970 Des Moines Art Center, purchased with funds from the Coffin Fine Arts Trust, Nathan Emery Coffin Collection 1988 © The Estate of Eva Hesse enlarge When one reflects upon the pedagogic practice of Josef Albers it is his colour instruction that likely first comes to mind. The former Bauhaus master’s 1963 publication Interaction of Color and its subsequent paperback editions have long been standard texts and the significance of his perception-based model of ‘color action’ in which visual relationships are developed rather than taken as given cannot be understated in terms of its importance both to art making and art instruction. Yet several of Albers’ students are known for their innovative use of material (like fibreglass and polyester resin in the case of Eva Hesse ) despite having been brilliant colourists in their own right.1 This seeming anomaly can be addressed, in part, by looking more deeply at the principles that underscored Albers’ teaching. For Albers, colour was in constant flux. In his instruction he emphasised its relativity as material and its role in creating visual relationships, especially those causing optical estrangement. But in doing so Albers taught his students more than the interaction of colour; he instilled in them a general approach to all material and means of engaging it in design. -

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions Cyanotype Formula, Mixing and Exposing Instructions 1. Dissolve 40 g (approximately 2 tablespoons) Potassium Ferricyanide in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create STOCK SOLUTION A. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. 2. Dissolve 100 g (approximately .5 cup) Ferric Ammonium Citrate in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create if you have Chemistry Open Stock START HERE STOCK SOLUTION B. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. If using the Cyanotype Sensitizer Set, simply fill each bottle with water, shake and allow 24 hours for the powders to dissolve. 3. In subdued lighting, mix equal parts SOLUTION A and SOLUTION B to create the cyanotype sensitizer. Mix only the amount you immediately need, as the sensitizer is stable just 2-4 hours. if you have the Sensitizer Set START HERE 4. Coat paper or fabric with the sensitizer and allow to air dry in the dark. Paper may be double-coated for denser prints. Fabric may be coated or dipped in the sensitizer. Jacquard’s Cyanotype Fabric Sheets and Mural Fabrics are pre-treated with the sensitizer (as above) and come ready to expose. 5. Make exposures in sunlight (1-30 minutes, depending on conditions) or under a UV light source, placing ob- jects or a film negative on the coated surface to create an image. (Note: Over-exposure is almost always preferred to under-exposure.) The fabric will look bronze in color once fully exposed. 6. Process prints in a tray or bucket of cool water. Wash for at least 5 minutes, changing the water periodically, if you have until the water runs clear. -

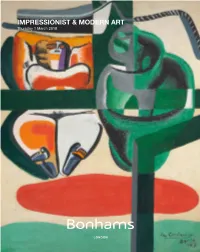

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff

SYMPOSIUMS 1 Michel Frizot Roxane Jubert Victor Margolin Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff Collected papers from the symposium “Photo /Graphisme“, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 20 October 2007 © Éditions du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2008. © The authors. All rights reserved. Jeu de Paume receives a subsidy from the Ministry of Culture and Communication. It gratefully acknowledges support from Neuflize Vie, its global partner. Les Amis and Jeunes Amis du Jeu de Paume contribute to its activities. This publication has been made possible by the support of Les Amis du Jeu de Paume. Contents Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: 5 the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 Roxane Jubert Typophoto. A major shift in visual communication 13 Victor Margolin The many faces of photography in the Weimar Republic 29 Michel Wlassikoff Futura, Europe and photography 35 Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 The fact that my title refers to technique rather than aesthetics reflects what I take to be a constant: in the case of photography (and, if I might dare to say, representation), technical processes and their development are the mainsprings of innovation and creation. In other words, the technique determines possibilities which are then perceived and translated by operators or others, notably photographers. With regard to photo/graphics, my position is the same: the introduction of photography into graphics systems was to engender new possibilities and reinvigorate the question of graphic design. And this in turn raises another issue: the printing of the photograph, which is to say, its assimilation to both the print and the illustration, with the mass distribution that implies. -

The Fine Art of Photography Eighth Annual Juried Photography Exhibition 2018 Prospectus

THE FINE ART OF PHOTOGRAPHY EIGHTH ANNUAL JURIED PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITION 2018 PROSPECTUS Categories: • Color • Black and White • Non-Traditional (Please note that the Judges’ assessment of which category an entry will be judged is final.) AwarDs: • $500 Best in Show, • Each Category: $250 First Place, $100 Second Place, • Two Honorable Mentions per category Color and Black and White Categories: This is traditional photography. The image has conventional post processing techniQues that enhance the image appearance without changing the pictorial content. Edits and/or effects that changes an image’s appearance from being a normal photograph may be categorized as Digitally Enhanced. Cropping, sharpening, and removal of obtrusive artifacts such as dust specks are allowed. Black and White includes monochromatic and sepia tones. Non-TraDitional Photography (incluDes the following) • Digitally EnhanceD: An image that does not meet the stricter reQuirements for the Color or Blank & White categories, or which has been digitally enhanced beyond the appearance of a photograph. It may have subjects or lighting added, removed or otherwise modified to create the image. • Vintage anD Alternative Printing Processes: Despite having been pioneered decades ago, alternative- printing processes — the photogram, daguerreotype, tintype, collodion, Mordançage and others — are still widely practiced. The 21st century has witnessed increased popularity among these and other organic printing methods, as photographers gravitate to the uniQue, unpredictable and fascinating print characteristics achievable through these time-honored techniQues. This is the perfect opportunity to show off your darkroom skill and creative vision. • Pinhole/Plastic Camera Imagery: This category includes analog photography, e.g. pinhole cameras and plastic cameras like the Holga, Diana and Lomo. -

SELECTED PHOTOGRAPHS from Brassaï to Cindy Sherman from Brassaï to Cindy Sherman

T +49 (0)30 - 211 54 61 | F +49 (0)30 - 218 11 97 |[email protected] 97 54 |F+49T +49 61 (0)30 11 (0)30 -218 -211 |www.kunsthandel-maass.de Kunsthandel Jörg Maaß |Rankestraße Berlin |10789 24 Kunsthandel Jörg Maaß SELECTED PHOTOGRAPHS From Brassaï to Cindy Sherman · 2009 SELECTED PHOTOGRAPHS From Brassaï to Cindy Sherman Cindy Brassaïto From 2 SELECTED PHOTOGRAPHS From Brassaï to Cindy Sherman 2 FROM BRASSAÏ TO CINDY SHERMAN 22 selected photographs For a number of years we have been gathering together a took Europe by storm between the two world wars, displaying collection of photographs which has evolved into a substantial infl uences from the Bauhaus, Surrealism and Neue Sachlichkeit group, but has never been shown publicly. A selection of which (New Objectivity) movements. Some examples of artists who we would now like to present in this catalog and exhibition. Our were proponents of the Neues Sehen or New Vision Photography intentions are to pro vide a wide and representative cross section are reproduced in our catalog. of our inventory, begin ning in the late 1920s and continuing up to the present day. We focus on American and European After the Second World War, the center of modern art moved photo graphy; black and white, as well as color. We have chosen from Europe to the United States, where photography had been works – in addition to the signifi cance of the individual artists – developing in a different direction. In the States, photography according to certain central themes: the nude, land scapes, por - was less dependent on the fi ne arts and can be seen as a per- traits and architecture, to name the most prominent. -

Bildgestaltung – Die Große Fotoschule 427 Seiten, Gebunden, September 2017 44,90 Euro, ISBN 978-3-8362-3940-0

Know-how für Fotografen. Leseprobe Gelungen ist die Fotografie nicht nur, wenn Sie sie für ein gutes Bild halten, sondern wenn sich der Inhalt Ihrer Fotografie den Betrachtern ebenso gut mitteilt. Den meisten unter Ihnen mag der erstgenannte Aspekt relativ ein- fach erscheinen, der zweite ist schon schwieriger – und genau um ihn geht es. Diese Leseprobe beginnt mit den Grundlagen ... Kapitel 1: »Bildgestaltung« Inhaltsverzeichnis Index Die Autoren Leseprobe weiterempfehlen André Giogoli, Katharina Hausel Bildgestaltung – Die große Fotoschule 427 Seiten, gebunden, September 2017 44,90 Euro, ISBN 978-3-8362-3940-0 www.rheinwerk-verlag.de/4001 KAPITEL 1 BILDGESTALTUNG Wozu und für wen fotografieren wir? Die meisten Aufnahmen entstehen, um geteilt und mitgeteilt zu werden. Fotografie ist ein Medium der Kommunikation. Die Bildsprache drückt ihren Inhalt aus. Die Gestaltung ist wichtig, um den Inhalt der Bilder deutlich zu vermitteln. Marokko, 2017 (Bild: Elena Breuer) KAPITEL 1 1.2 Der Impuls, Fotografien mitzuteilen In jedem Fall geht vom Motiv ein ästhetischer Reiz aus, optischen Dreieck. Sie kontrastieren mit dem hellen Bo- und darauf folgt unser Impuls zu fotografieren. Der Be- den. Inmitten des optischen Dreiecks gehen ein Mann BILDGESTALTUNG griff »ästhetisch« ist in diesem Zusammenhang nicht und eine Frau nach rechts, ihre Köpfe sind einander zu- Wozu oder für wen fotografieren? zwangsläufig als »schön« zu verstehen, sondern als sinn- geneigt. Der Mann hat weißes Haar, er trägt eine helle lich empfindbar, also wahrnehmbar. Es gibt auch eine Jacke und eine dunkle Hose. Die Frau hat dunkles Haar, Ästhetik des Hässlichen, des Schreckens oder des Erha- trägt eine dunkle Jacke und eine weiße Hose.