Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20Th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography A Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum Brings Together Iconic Masterpieces and Unknown Avant-garde Artists from the Israel Museum’s Collections On view at Israel Museum July 16, 2019 – January 5, 2020 Jerusalem, Israel, August 1, 2019 – Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum delves into the work of photographers who shaped and defined photography between 1900-1945, helping to expand public understanding of early modern photography through a presentation that brings together acclaimed and unknown works by male and female artists. Featuring around 200 works from seminal artists such as Alfred Stieglitz, August Sander, Edward Weston, and Man Ray, alongside lesser-known photographers such as Liselotte Grschebina, ringl+pit, Laure Albin Guillot, and Frieda Meyer Jakobson, the exhibition fosters a deeper level of understanding around the development of cultural production at the time and uncovers unexpected and surprising discoveries, including a personal note written by Alfred Stieglitz on the back of the 1916 print Portrait of Marie Rapp. The exhibition also fosters contemporary relevancy around the works, connecting camera techniques by Modern photographers to current images captured by cell phones. “Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum showcases the Museum’s incredible photography collection and demonstrates its continued commitment to supporting the exploration and exhibition of images through robust programming and curatorial expertise,” said Ido Bruno, Anne and Jerome Fisher Director of the Israel Museum. “I am thrilled that our visitors will have the opportunity to experience this unique selection of iconic Modern photographs drawn from the Museum’s extensive holdings, many which are going on display for the first time.” Drawing on a recent gift from collector Gary B. -

MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021

GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF Member of the group “Cercle et Carré”, Marcelle Cahn's works from the very first period of her production are linked to expressionism thanks to her expressionist master Lovis Corinth in Berlin, then to cubism by joining the courses of the Modern Academy in the studio of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant in Paris where she did not go beyond abstraction, proposing a personal style combining geometric rigor and sensitivity; finally she joined purism and constructivism. After the War, she regularly participates in the “Salon des Réalités Nouvelles”, where she shows her abstract compositions. It is at this time that she will define the style that characterizes her paintings with white backgrounds crossed by a play of lines or forms in relief, it is also at this time that she realizes her astonishing collages created from everyday supports: envelopes, labels, photographs, postcards, stickers. Marcelle Cahn (at the center) surrounded by the members of the group “Cercle et Carré” (photograph taken in 1929) : Francisca Clausen, Florence Henri, Manolita Piña de Torres García, Joaquín Torres García, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, Pierre Daura, Sophie Tauber-Arp, Michel Seuphor, Friedrich Vordemberge Gildewart, VeraIdelson, Luigi Russolo, Nina Kandinsky, Georges Vantongerloo, Vassily Kandinsky and Jean Gorin. 2 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF BIOGRAPHY Born March 1st 1895 at Strasbourg, died September 21st 1981 at Neuilly-sur-Seine 1915-1920 From 1915 to 1919, she lives in Berlin, where she was a student of Lovis Corinth. Her first visit to Paris came in 1920 where she also tries her hand at small geometrical drawings. -

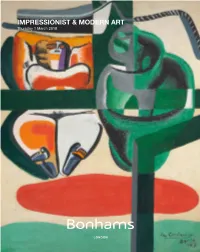

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those

11 71 126 Bruno Adler Lotte Collein Walter Gropius Weimar in Those Days Photography The Idea of the at the Bauhaus Bauhaus: The Battle 16 for New Educational Josef Albers 76 Foundations Thirteen Years Howard at the Bauhaus Dearstyne 131 Mies van der Rohe’s Hans 22 Teaching at the Haffenrichter Alfred Arndt Bauhaus in Dessau Lothar Schreyer how i got to the and the Bauhaus bauhaus in weimar 83 Stage Walter voxel 30 The Bauhaus 137 Herbert Bayer Style: a Myth Gustav Homage to Gropius Hassenpflug 89 A Look at the Bauhaus 33 Lydia Today Hannes Beckmann Driesch-Foucar Formative Years Memories of the 139 Beginnings of the Fritz Hesse 41 Dornburg Pottery Dessau Max Bill Workshop of the State and the Bauhaus the bauhaus must go on Bauhaus in Weimar, 1920-1923 145 43 Hubert Hoffmann Sandor Bortnyik 100 the revival of the Something T. Lux Feininger bauhaus after 1945 on the Bauhaus The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Idea 150 50 Hubert Hoffmann Marianne Brandt 117 the dessau and the Letter to the Max Gebhard moscow bauhaus Younger Generation Advertising (VKhUTEMAS) and Typography 55 at the Bauhaus 156 Hin Bredendieck Johannes Itten The Preliminary Course 121 How the Tremendous and Design Werner Graeff Influence of the The Bauhaus, Bauhaus Began 64 the De Stijl group Paul Citroen in Weimar, and the 160 Mazdaznan Constructivist Nina Kandinsky at the Bauhaus Congress of 1922 Interview 167 226 278 Felix Klee Hannes Meyer Lou Scheper My Memories of the On Architecture Retrospective Weimar Bauhaus 230 283 177 Lucia Moholy Kurt Schmidt Heinrich Kdnig Questions -

Polish Photomontage Jaromir Funke Paul Outerbridge

Polish Photomontage Jaromir Funke Paul Outerbridge photograph by Jaromir Funke, 1932 Galerie Schurmarm & Kicken January 1978 Editor and Publisher Colin Osman Co-Editor Peter Turner Number 163 Advertising & Production Rick Osman Book Department Terry Rossiter Subscriptions Howard Lerner Circulation Dave Osman Contents The Churchill Outrage With the death of the widow of Sir Winston Churchill it has been revealed that she Views/forum 4 ordered her servants to destroy the highly-controversial portrait of him painted by the famous artist, Graham Sutherland. It had been common knowledge that both she and Sir Photomontage in Poland Winston disliked the picture intensely but this was the first time its fate was known. Urszula Czartoryska 6 Graham Sutherland's comments on this do not really show him to be moved with great indignation but it is important that someone should protest at what is, in fact, an outrage. The photograph and Some years ago, when doing a survey of the use of cameras in various museums I was the museum 12 amused to discover that even some of our most respected institutions had learned the hard way that when you purchase a painting you do not purchase the copyright or any Jaromir Funke— right to reproduce it. This fact of life is much better known among photographers and the sentimental reminiscences purchasers of photographs but it should be remembered basically that at all times the Anna Farova 14 purpose of copyright was to protect the original author, the photographer or the artist. It is only through commercial exigency that it has been expanded so as to include agents, Jaromir Funke 15 employers etc. -

Self-Portrait: the Photographer's Persona 1840-1985

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release October 1985 SELF-PORTRAIT: THE PHOTOGRAPHER'S PERSONA 1840-1985 November 7, 1985 - January 7, 1986 SELF-PORTRAIT: THE PHOTOGRAPHER'S PERSONA 1840-1985, an exhibition of self- portraits taken by major European and American photographers of the last century, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on November 7, 1985. Organized by Susan Kismaric, associate curator in the Department of Photography, this highly selective survey provides a fascinating record of artistic exploration through one of the most intimate and revealing of art forms. Andre Kertesz, Eadweard Muybridge, Felix Nadar, August Sander, Imogen Cunningham, and Alfred Steiglitz are among the masters of photography represented (partial list of artist names attached). Since photography's origins in the late nineteenth century, artists have expressed the idea that the self-portrait is a form of performance. Kismaric states, "The photographer who attempts an investigation of his physiognomy or personality or who consciously or unconsciously projects an idea about himself enacts a role. The plasticity of photography allows the self-portraitist to experiment, to assume many identities; in self-portraiture the photographer can become the hero, the adventurer, the aesthete--or a neutral ground upon which artistic experiments are played out." One of the earliest photographs included in the exhibition is a modern print of Hippolyte Bayard's Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840), the artist's amusing response to Daguerre's announcement of the invention of photography. Bayard had perfected a method of making photographs at the same time as Daguerre, but it was Daguerre whose method was first published and who received the acclaim. -

Berlin, 10 April 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION Museum Für

Berlin, 10 April 2019 GENERALDIREKTION PRESSE – KOMMUNIKATION – SPONSORING BACKGROUND INFORMATION Stauffenbergstraße 41 10785 Berlin Museum für Fotografie Bauhaus and Photography. On New Visions in Contemporary Art 11 April – 25 August 2019 MECHTILD KRONENBERG HEAD OF PRESS, COMMUNICATION, SPONSORSHIP László Moholy-Nagy and the FiFo László Moholy-Nagy – Bauhaus artist and pioneer of media art – co- MARKUS FARR curated the legendary exhibition Film und Foto (FiFo) in 1929, which was PRESS OFFICER set up by the Deutscher Werkbund in the exhibition halls on Interimthea- terplatz in Stuttgart. The FiFo, which subsequently travelled to Zurich, Tel: +49 30 266 42 3402 Mobile: +49 151 527 53 886 Berlin, Gdansk, Vienna, Agram, Munich, Tokyo and Osaka, presented a total of around 200 artists with 1200 works and showed the creations of [email protected] the international film and photography scene of those years. Moholy-Nagy www.smb.museum/presse curated the hall, which reflected the history and present of photography. His artistic perspective on the history of photography and his efforts to provide a comprehensive overview of the contemporary fields of photo- graphic application were fundamental. At the exit of the large hall, Moholy- Nagy suggestively posed the question of the future of photographic devel- opment. On the basis of extensive scientific research, the Moholy-Nagy room was virtually reconstructed with approximately 300 exhibits. The exhibition Film und Foto took its starting point in 1929 in Stuttgart, but was opened only a short time later in the Kunstgewerbemuseum (today: Gropius Bau) in Berlin. In the inner courtyard of the museum, large parti- tion walls were erected to present the numerous photo exhibits. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 19 (Winter, 1981), pp. 3-34 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778652 . Accessed: 08/09/2013 11:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.147.202.25 on Sun, 8 Sep 2013 11:08:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism* ROSALIND KRAUSS I open my subject with a comparison. On the one hand, thereis Man Ray's Monument to de Sade, a photograph made in 1933 for the magazine Le Surreal- isme au servicede la rekvolution.On the other,there is a self-portraitby Florence Henri, given wide exposure by its appearance in the 1929 Foto-Auge,a publica- tion thatcatalogued theEuropean avant-garde'sposition withregard to photogra- phy.' This comparison involves, then, a slight adulteration of my subject- surrealism-by introducingan image deeply associated with the Bauhaus. For FlorenceHenri had been a studentof Moholy-Nagy,although at the timeof Foto- Auge she had returnedto Paris. -

Art for All: Photographs to Touch a Tactile Image Kit

Art For All: Photographs to Touch A Tactile Image Kit Elysée Lausanne Art For All: Photographs to Touch Elysée Lausanne A Tactile Image Kit 2/912/14 Art For All: Photographs to Touch A Tactile Image Kit For a Tactile Approach to Photography Convinced that access to art is a fundamental right, the Musée de l’Élysée has created an innovative project aimed at making photography accessible to blind audiences. Around thirty important works from the Museum’s collections have been transcribed into tactile images and posted online, making them accessible to blind audiences worldwide. Entitled Art For All: Photographs to Touch and designed with the invaluable collaboration of the Centre pédagogique pour élèves handicapés de la vue (CPHV) in Lausanne, this project offers a sensory approach to the image through the fingers instead of the eyes, thanks to a transformation of the photographic image making its different forms, subjects and contrasts palpable - and thus readable. Wishing to offer inclusive activities fostering dialogue and sharing, the Musée de l’Élysée conceived this kit as a tool that can be used by two people or more. It aims to enhance cooperation and dialogue between blind and sighted people, allowing them to discover photography and its heritage together. The activity begins with the reading of the text, introducing the artwork. It details the composition of the image and places the photograph in its historical, technical and aesthetic context. Then, the analysis of the tactile image starts. Along with its legend in braille, the duo decrypts the various elements of the artwork. The tactile images can be downloaded as a kit, and printed individually in A4 format with a tactile image printer. -

Entfernt Frauen Des Bauhauses Während Der NS-Zeit – Verfolgung Und Exil Frauen Und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 2

www.claudia-wild.de: Frauen und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 1 Entfernt Frauen des Bauhauses während der NS-Zeit – Verfolgung und Exil www.claudia-wild.de: Frauen und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 2 Frauen und Exil, Band 5 Herausgegeben von Inge Hansen-Schaberg www.claudia-wild.de: Frauen und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 3 Entfernt Frauen des Bauhauses während der NS-Zeit – Verfolgung und Exil Herausgegeben von Inge Hansen-Schaberg Wolfgang Thöner Adriane Feustel www.claudia-wild.de: Frauen und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 4 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-86916-212-6 Umschlaggestaltung: Thomas Scheer Umschlagabbildung: Gertrud Arndt: Otti Berger in der Eingangshalle des Bauhauses, Dessau 1930 (1932?) Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwer- tung, die nicht ausdrücklich vom Urheberrechtsgesetz zugelassen ist, Bedarf der vor- herigen Zustimmung des Verlages. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Bearbeitungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. © edition text + kritik im Richard Boorberg Verlag GmbH & Co KG, München 2012 Levelingstraße 6a, 81673 München www.etk-muenchen.de Satz: Claudia Wild, Konstanz Druck und Buchbinder: Laupp & Göbel GmbH, Talstraße 14, 72147 Nehren www.claudia-wild.de: Frauen und Exil, Band 5/13.09.2012/Seite 7 Inhalt Vorwort 9 INGE HANSEN-SCHABERG, WOLFGANG THÖNER UND ADRIANE FEUSTEL: Entfernt: Frauen des Bauhauses während der NS-Zeit – Verfolgung und Exil 11 INGE HANSEN-SCHABERG: Die Bildungsidee des Bauhauses und ihre Materialisierung in der künstlerischen Tätigkeit ausgewählter Absolventinnen 17 RAHEL E.