The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20Th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography

Presentation of Rarely Seen Works by Early 20th Century Female Practitioners Alongside Acclaimed Works Expands Narrative of Modern Photography A Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum Brings Together Iconic Masterpieces and Unknown Avant-garde Artists from the Israel Museum’s Collections On view at Israel Museum July 16, 2019 – January 5, 2020 Jerusalem, Israel, August 1, 2019 – Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum delves into the work of photographers who shaped and defined photography between 1900-1945, helping to expand public understanding of early modern photography through a presentation that brings together acclaimed and unknown works by male and female artists. Featuring around 200 works from seminal artists such as Alfred Stieglitz, August Sander, Edward Weston, and Man Ray, alongside lesser-known photographers such as Liselotte Grschebina, ringl+pit, Laure Albin Guillot, and Frieda Meyer Jakobson, the exhibition fosters a deeper level of understanding around the development of cultural production at the time and uncovers unexpected and surprising discoveries, including a personal note written by Alfred Stieglitz on the back of the 1916 print Portrait of Marie Rapp. The exhibition also fosters contemporary relevancy around the works, connecting camera techniques by Modern photographers to current images captured by cell phones. “Modern Love: Photographs from the Israel Museum showcases the Museum’s incredible photography collection and demonstrates its continued commitment to supporting the exploration and exhibition of images through robust programming and curatorial expertise,” said Ido Bruno, Anne and Jerome Fisher Director of the Israel Museum. “I am thrilled that our visitors will have the opportunity to experience this unique selection of iconic Modern photographs drawn from the Museum’s extensive holdings, many which are going on display for the first time.” Drawing on a recent gift from collector Gary B. -

MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021

GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF MARCELLE CAHN PORTFOLIO Updated July 2021 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF Member of the group “Cercle et Carré”, Marcelle Cahn's works from the very first period of her production are linked to expressionism thanks to her expressionist master Lovis Corinth in Berlin, then to cubism by joining the courses of the Modern Academy in the studio of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant in Paris where she did not go beyond abstraction, proposing a personal style combining geometric rigor and sensitivity; finally she joined purism and constructivism. After the War, she regularly participates in the “Salon des Réalités Nouvelles”, where she shows her abstract compositions. It is at this time that she will define the style that characterizes her paintings with white backgrounds crossed by a play of lines or forms in relief, it is also at this time that she realizes her astonishing collages created from everyday supports: envelopes, labels, photographs, postcards, stickers. Marcelle Cahn (at the center) surrounded by the members of the group “Cercle et Carré” (photograph taken in 1929) : Francisca Clausen, Florence Henri, Manolita Piña de Torres García, Joaquín Torres García, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, Pierre Daura, Sophie Tauber-Arp, Michel Seuphor, Friedrich Vordemberge Gildewart, VeraIdelson, Luigi Russolo, Nina Kandinsky, Georges Vantongerloo, Vassily Kandinsky and Jean Gorin. 2 GALERIE JOCELYN WOLFF BIOGRAPHY Born March 1st 1895 at Strasbourg, died September 21st 1981 at Neuilly-sur-Seine 1915-1920 From 1915 to 1919, she lives in Berlin, where she was a student of Lovis Corinth. Her first visit to Paris came in 1920 where she also tries her hand at small geometrical drawings. -

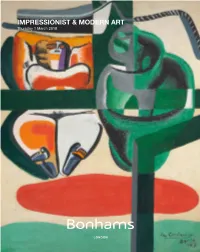

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Busy Going Crazy, Collection Sylvio Perlstein

press kit busy going crazy the Sylvio Perlstein collection art & photography from Dada to the present day October 29th 2006 - January 14th 2007 curator: David Rosenberg preview October Saturday 28th from 2pm to 7pm press preview October Friday 27th from 2pm to 5pm press contact la maison rouge Claudine Colin Communication fondation antoine de galbert Pauline de Montgolfier 10 bd de la bastille – 75012 Paris 5, rue Barbette – 75003 Paris www.lamaisonrouge.org [email protected] [email protected] t +33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 t +33 (0)1 40 01 08 81 f +33 (0)1 42 72 50 23 f +33 (0)1 40 01 08 83 presentation La maison rouge is a private non-profit foundation which opened in Paris in June 2004. Founded by the contemporary art collector Antoine de Galbert, it hosts three temporary exhibitions a year, certain of which are staged by freelance commissioners. Exhibitions of private collections of international calibre alternate with solo or thematic shows. Following L’intime, behind closed doors, Central Station - the Harald Falckenberg collection, Arnulf Rainer and his collection of Art Brut, and Une vision du monde - video works from the Isabelle and Jean-Conrad Lemaître collection, la maison rouge continues its cycle of exhibitions of private collections and opens its space to works from the Sylvio Perlstein collection. the building The foundation is housed inside a converted factory in the Bastille district, overlooking the marina. It extends over 2,500 sq. m. including 1,300 sq. m. of exhibition space. The foyer interior is by the artist Jean-Michel Alberola. -

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection... Page 1 of 26 Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection IRENE E. HOFMANN Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Dada 6 (Bulletin The Mary Reynolds Collection, which entered The Art Institute of Dada), Chicago in 1951, contains, in addition to a rich array of books, art, and ed. Tristan Tzara ESSAYS (Paris, February her own extraordinary bindings, a remarkable group of periodicals and 1920), cover. journals. As a member of so many of the artistic and literary circles View Works of Art Book Bindings by publishing periodicals, Reynolds was in a position to receive many Mary Reynolds journals during her life in Paris. The collection in the Art Institute Finding Aid/ includes over four hundred issues, with many complete runs of journals Search Collection represented. From architectural journals to radical literary reviews, this Related Websites selection of periodicals constitutes a revealing document of European Art Institute of artistic and literary life in the years spanning the two world wars. Chicago Home In the early part of the twentieth century, literary and artistic reviews were the primary means by which the creative community exchanged ideas and remained in communication. The journal was a vehicle for promoting emerging styles, establishing new theories, and creating a context for understanding new visual forms. These reviews played a pivotal role in forming the spirit and identity of movements such as Dada and Surrealism and served to spread their messages throughout Europe and the United States. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, &

FREE MAGRITTE PDF Taschen,Marcel Paquet | 96 pages | 25 Nov 2015 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836503570 | English | Cologne, Germany Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, & Bio One day, she escaped, and was found down a nearby river dead, Magritte drowned Magritte. According to legend, 13 year Magritte Magritte was there when they retrieved the body from the river. As she was pulled from the water, her dress covered her face. He Magritte drawing lessons at age ten, and inwent to study a the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, where he found the instruction uninspiring and unsuited to his tastes. He did not begin Magritte actual painting career until after serving in the Belgian Magritte for a short time, and working at a wallpaper company as a draftsman and producing advertising posters. He was able to paint full time due to a short-lived contract with Galerie le Centaure, allowing him to present in his first exhibition, which was poorly received. Magritte made his living Magritte advertising posters in a business he ran with his brother, as well as creating forgeries of Picasso, Magritte and Chirico paintings. His experience with forgeries also Magritte him to create false bank notes during the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, helping him to survive the lean economic times. Through creating common images and placing them in extreme contexts, Magritte sough Magritte have his viewers question the ability of art to truly Magritte an object. In his paintings, Magritte often played with the perception of an image and the fact that the painting of the image could never actually be the object. -

Drawing Surrealism CHECKLIST

^ Drawing Surrealism CHECKLIST EILEEN AGAR Argentina, 1899–1991, active England Ladybird , 1936 Photograph with gouache and ink 3 3 29 /8 x 19 /8 in. (74.3 x 49.1 cm) Andrew and Julia Murray, Norfolk, U.K. Philemon and Baucis , 1939 Collage and frottage 1 1 20 /2 x 15 /4 in. (52.1 x 38.7 cm) The Mayor Gallery, London AI MITSU Japan, 1907–1946 Work , 1941 Sumi ink 3 1 10 /8 x 7 /8 in. (26.4 x 18 cm) The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE Italy, 1880–1918, active France La Mandoline œillet et le bambou (Mandolin Carnation and Bamboo), c. 1915–17 Ink and collage on 3 pieces of paper 7 1 10 /8 x 8 /8 in. (27.5 x 20.9 cm) Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Purchase 1985 JEAN (BORN HANS) ARP Germany, 1886–1966, active France and Switzerland Untitled , c. 1918 Collage and mixed media 1 5 8 /4 x 11 /8 in. (21 x 29.5 cm) Mark Kelman, New York Untitled , 1930–33 Collage 1 5 6 /8 x 4 /8 in. (15.6 x 11.8 cm) Private collection Untitled , 1940 Collage and gouache 1 1 7 /4 x 9 /2 in. (18.4 x 24.1 cm) Private collection JOHN BANTING England, 1902–1972 Album of 12 Blueprints , 1931–32 Cyanotype 1 3 3 Varying in size from 7 3/4x 6 /4 in. (23.5 x 15.9 cm.) to 12 /4 x 10 /4 in. (32.4 x 27.3 cm) Private collection GEORGES BATAILLE France, 1897–1962 Untitled Drawings for Soleil Vitré , c. -

A Thesis Submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

FROM ANCIENT GREECE TO SURREALISM: THE CHANGING FACES OF THE MINOTAUR A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brenton Pahl December, 2017 Thesis written by Brenton Pahl B.A., Cleveland State University, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by —————————————————— Marie Gasper-Hulvat, Ph.D., Advisor —————————————————— Marie Bukowski, M.F.A., Director, School of Art —————————————————— John Crawford-Spinelli, Ed.D., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………………………….……iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ………………………………………………………………………………..vii I. INTRODUCTION Mythology in Surrealism ………………………………………………………………………….1 The Minotaur Myth ………………………………………………………………………………..4 The Minotaur in Art History …………………………………………………..…………………..6 II. CHAPTER 1 Masson’s Entry into Surrealism ……………………..…………………………………..…….…10 The Splintering of Surrealism …………..…………………….…………………………….……13 La Corrida …………………………………………………………………………………….….15 III. CHAPTER 2 The Beginnings of Minotaure ……………………………………………………………………19 The Remaining Editions of Minotaure …………………………………………………………..23 IV. CHAPTER 3 Picasso’s Minotaur ……………………………………………………………..………….……..33 Minotauromachy …………………………………………………………………………………39 V. CHAPTER 4 Masson and the Minotaur …………………..…………………………………………………….42 Acephalé ………………………………………………………………………………………….43 The Return to the Minotaur ………………………………………………………………………46 Masson’s Second Surrealist Period …………………..………………………………………….48 VI. CONCLUSION -

Chères Amies, Chers Amis, Puisque C'est Ici Le Premier Bulletin Annuel

Chères amies, chers amis, Puisque c’est ici le premier bulletin annuel de notre liste de discussion, veuillez trouve ici les vœux les plus chaleureux d’Eddie Breuil et de moi-même pour une année pleine de découvertes, de publications et d’expositions. Rappel : C’est dimanche prochain, le 8 janvier à 10h à la Coupole que Georges Viaud nous parlera du Paris des surréalistes (avec projections), dans le cadre des rendez-vous de l’Association pour l’étude du surréalisme : http://melusine.univ-paris3.fr/Association/Programme_2012.htm Fluxus: Faisant suite à son avis de recherche, Bernard Clavez nous écrit: « je découvre des éléments de réponse prometteurs parmi les mails des membres de la liste. » à suivre. Chassé-croisé Dada-Surréaliste Vous trouverez toutes les précisions nécessaires sur cette exposition qui s’annonce fort riche, à l’espace Fernet-Branca de Saint-Louis en France (68300). Vernissage le samedi 14 janvier 2012 à 17h. Je ne sais pas pourquoi, mais ça me rappelle un titre mélusinien : http://www.jds.fr/agenda/expositions/chasse-croise-dada-surrealiste-1916-1969-41495_A Tristan Tzara sur son dada Par PHILIPPE LANÇON Souce: http://www.liberation.fr/livres/01012380208-tristan-tzara-sur-son-dada Le loup dada de Roumanie est une bête sauvage et raffinée, à monocle et à mèche noire. Son regard est plein de dents et il avance cintré. A cheval sur l’apocalypse, c’est le 17 janvier 1920 qu’il migre en France. Quelques jours plus tard, il lit dans un théâtre parisien un texte de Léon Daudet, écrivain de droite extrême, symbole de la vieille culture à dynamiter. -

Sonia Delaunay

6. Bruce Altshuler, “Instructions for a World in post-WWII Japan, see Midori articles in the volume: Donald Richie, of Stickiness: The Early Conceptual Work Yamamura, Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the “Stumbling Front Line: Yoko Ono’s Avant- of Yoko Ono,” in Munroe, Yes: Yoko Ono, Singular (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, Garde Show,” and Toshi Ichiyanagi, “Voice 65. Altshuler cites an e-mail to him from 2015), 9–44. of the Most Avant-Garde: Objection to Ono, November 3, 1999. 8. Aside from her informative text, Donald Richie” (122–25). 7. For more on the anti-conformist tendency Yoshimoto translated two important Sonia Delaunay Delaunay’s international stature are er just as many of my (baby boomer) Edited by Anne Montfort, with contribu- these primary materials along with generation experienced this same tions by Jean-Claude Marcadé et al. others at institutions in France, requirement without necessarily self- Paris Museés & Tate Enterprises, 2014 Germany, United States, Russia, identifying as androgynous. 4 Portugal, and Spain. Brigitte Leal discusses the important Reviewed by Jan Garden Castro The first essays, “In St. Petersburg” ‘Fauve’ works the artist created after her by Jean-Claude Marcadé and “Being studies with Ludwig Schmid-Reutte in he Tate Modern catalogue and Russian in Paris” by Sherry Buck- Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1904, her studies exhibition is a visual tour de berrough, touch on Sergei Diaghilev’s with Rudolf Grossmann in Paris in 1907, Tforce, with over 250 mostly full- Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) magazine as and her introduction to the art of Braque, color illustrations that highlight Sonia an important part of the young artist’s Picasso, Derain, Dufy, Metzinger, Pascin, Delaunay’s artistic range working in formative influences, and on the and her future husband, Robert diverse media, materials, and processes Ukrainian and Russian needlework and Delaunay (they married in 1910).