Picasso, a Model Shaping Dalí's “Spectral Surrealism”: Towards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Cubism Futurism Art Deco

20TH Century Art Early 20th Century styles based on SHAPE and FORM: Cubism Futurism Art Deco to show the ‘concept’ of an object rather than creating a detail of the real thing to show different views of an object at once, emphasizing time, space & the Machine age to simplify objects to their most basic, primitive terms 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Pablo Picasso 1881-1973 Considered most influential artist of 20th Century Blue Period Rose Period Analytical Cubism Synthetic Cubism 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Early works by a young Picasso Girl Wearing Large Hat, 1901. Lola, the artist’s sister, 1901. 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Blue Period (1901-1904) Moves to Paris in his late teens Coping with suicide of friend Paintings were lonely, depressing Major color was BLUE! 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Blue Nude, 1902. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Tragedy, 1903. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Le Gourmet, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s work at the National Gallery (DC) 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Rose Period (1904-1906) Much happier art than before Circus people as subjects Reds and warmer colors Pablo Picasso, Harlequin Family, 1905. ROSE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Pablo Picasso, La Familia de Saltimbanques, 1905. -

Synthetic Cubism at War: New Necessities, New Challenges

RIHA Journal 0250 | 02 September 2020 Synthetic Cubism at War: New Necessities, New Challenges. Concerning the Consequences of the Great War in the Elaboration of a Synthetic-Cubist Syntax Belén Atencia Conde-Pumpido Abstract When we talk about the Synthetic Cubism period, what exactly are we referring to? What aesthetic possibilities and considerations define it insofar as its origin and later evolution are concerned? To what extent did the disorder that the Great War unleashed, with all its political, sociological and moral demands, influence the reformulation of a purely synthetic syntax? This article attempts to answer these and other questions relating to the sociological-aesthetic interferences that would influence the Parisian Cubist style of the war years, and in particular the works of Juan Gris, María Blanchard, Jacques Lipchitz and Jean Metzinger during the spring and summer that they shared with one another in 1918, until it consolidated into what we now know as Crystal Cubism. Contents Cubism and war. The beginning of the end or infinite renewal? At a crossroads: tradition, figuration, synthesis and abstraction The Beaulieu group, the purification of shape and the crystallization of Cubism in 1918 and 1919 Epilogue Cubism and war. The beginning of the end or infinite renewal? [1] The exhibition "Cubism and War: the Crystal in the Flame", held in the Picasso Museum in Barcelona in 2016,1 highlighted the renewed production undertaken in Paris during the war years by a small circle of artists who succeeded in taking Synthetic Cubism to its ultimate consequences. 1 Cubism and War: the Crystal in the Flame, ed. -

Linking Local Resources to World History

Linking Local Resources to World History Made possible by a Georgia Humanities Council grant to the Georgia Regents University Humanities Program in partnership with the Morris Museum of Art Lesson 5: Modern Art: Cubism in Europe & America Images Included_________________________________________________________ 1. Title: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881– 1973) Date: 1907 Medium: Oil on canvas Location: Museum of Modern Art, New York 2. Title: untitled (African mask) Artist: unknown, Woyo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo Date: c. early 20th century Medium: Wood and pigment Size: 24.5 X 13.5 X 6 inches Location: Los Angeles County Museum of Art 3. Title: untitled (African mask) Artist: Unknown, Fang Tribe, Gabon Date: c. early 20th century Medium: Wood and pigment Size: 24 inches tall Location: Private collection 4. Title: Abstraction Artist: Paul Ninas (1903–1964 Date: 1885 Medium: Oil on canvas Size: 47.5 x 61 inches Location: Morris Museum of Art 5. Title: Houses at l’Estaque Artist: Georges Braque (1882–1963) Date: 1908 Medium: Oil on Canvas Size: 28.75 x 23.75 inches Location: Museum of Fine Arts Berne Title: Two Characters Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881– 1973) Date: 1934 Medium: Oil on canvas Location: Museum of Modern Art in Rovereto Historical Background____________________________________________________ Experts debate start and end dates for “modern art,” but they all agree modernism deserves attention as a distinct era in which something identifiably new and important was under way. Most art historians peg modernism to Europe in the mid- to late- nineteenth century, with particularly important developments in France, so we’ll look at that time in Paris and then see how modernist influences affect artworks here in the American South. -

THE ARTISTIC COLLABORATION of PABLO PICASSO and JULIO GONZÁLEZ a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College

IRON DIALOGUE: THE ARTISTIC COLLABORATION OF PABLO PICASSO AND JULIO GONZÁLEZ A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Jason Trimmer June 2005 © 2005 Jason Trimmer All Rights Reserved This thesis entitled IRON DIALOGUE: THE ARTISTIC COLLABORATION OF PABLO PICASSO AND JULIO GONZÁLEZ by Jason Trimmer has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Joseph Lamb Associate Professor of Art History Raymond Tymas-Jones Dean of the College of Fine Arts TRIMMER, JASON A. M.F.A. June 2005. Art History Iron Dialogue: The Artistic Collaboration of Pablo Picasso and Julio González (69 pp.) Thesis Advisor: Joseph Lamb This paper analyzes the sculptural collaboration between Pablo Picasso and Julio González. It will examine each of the works born of the collaborative project at length, and discuss the major stylistic and thematic precursors to these works, both within each artist’s oeuvre and art history in general. During the collaboration, each artist’s unique sensibilities, skills, and styles merged to create just under a dozen works that have since resonated throughout the fields of art and art history. Also discussed will be the fact that these sculptures were created during the interwar period in Europe, which was a time of industrial, societal, and political upheaval. Each of these broad paradigm shifts is reflected within the works, and these works can, in fact, help to further our understanding of this tumultuous time period. While a good amount of important scholarship on the Picasso-González collaboration exists, much of it is spread across a number of years and a number of sources. -

Pablo Picasso & Cubism

Pablo Picasso & Cubism Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) was one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century. Picasso’s father was an art teacher and he encouraged Picasso to draw and paint at a young age. The style or way Picasso painted changed over his lifetime. When Picasso was in his early twenties his work became different from anyone else’s. His best friend died and Picasso felt alone. None of his paintings were selling and he was almost starving to death. Because of his mood, Picasso began to paint with a lot of blue. Blue can be a very sad color. He made all the people in his paintings look lonely and sad. Picasso’s Blue Period ended when he met and fell in love with a girl named Fernande. He started to paint in happier colors and happier things. This was the beginning of his Rose Period. Picasso painted a lot of circus people during this time. The Rose Period didn’t last very long because he found a new way to paint that was exciting and different. Cubism Cubism was the next and most famous style of painting Picasso developed. Cubism is one of the most important periods in the history of modern art. Picasso painted his subjects like they were broken up into little cubes. That is were the name Cubism came from. Picasso kept working with Cubism and changed it over the years. It became much more colorful and flatter looking. It became easier to see what Picasso was painting. Picasso wanted to show more than one side of his subject. -

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection... Page 1 of 26 Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection IRENE E. HOFMANN Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Dada 6 (Bulletin The Mary Reynolds Collection, which entered The Art Institute of Dada), Chicago in 1951, contains, in addition to a rich array of books, art, and ed. Tristan Tzara ESSAYS (Paris, February her own extraordinary bindings, a remarkable group of periodicals and 1920), cover. journals. As a member of so many of the artistic and literary circles View Works of Art Book Bindings by publishing periodicals, Reynolds was in a position to receive many Mary Reynolds journals during her life in Paris. The collection in the Art Institute Finding Aid/ includes over four hundred issues, with many complete runs of journals Search Collection represented. From architectural journals to radical literary reviews, this Related Websites selection of periodicals constitutes a revealing document of European Art Institute of artistic and literary life in the years spanning the two world wars. Chicago Home In the early part of the twentieth century, literary and artistic reviews were the primary means by which the creative community exchanged ideas and remained in communication. The journal was a vehicle for promoting emerging styles, establishing new theories, and creating a context for understanding new visual forms. These reviews played a pivotal role in forming the spirit and identity of movements such as Dada and Surrealism and served to spread their messages throughout Europe and the United States. -

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 19 (Winter, 1981), pp. 3-34 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778652 . Accessed: 08/09/2013 11:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.147.202.25 on Sun, 8 Sep 2013 11:08:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism* ROSALIND KRAUSS I open my subject with a comparison. On the one hand, thereis Man Ray's Monument to de Sade, a photograph made in 1933 for the magazine Le Surreal- isme au servicede la rekvolution.On the other,there is a self-portraitby Florence Henri, given wide exposure by its appearance in the 1929 Foto-Auge,a publica- tion thatcatalogued theEuropean avant-garde'sposition withregard to photogra- phy.' This comparison involves, then, a slight adulteration of my subject- surrealism-by introducingan image deeply associated with the Bauhaus. For FlorenceHenri had been a studentof Moholy-Nagy,although at the timeof Foto- Auge she had returnedto Paris. -

Drawing Surrealism CHECKLIST

^ Drawing Surrealism CHECKLIST EILEEN AGAR Argentina, 1899–1991, active England Ladybird , 1936 Photograph with gouache and ink 3 3 29 /8 x 19 /8 in. (74.3 x 49.1 cm) Andrew and Julia Murray, Norfolk, U.K. Philemon and Baucis , 1939 Collage and frottage 1 1 20 /2 x 15 /4 in. (52.1 x 38.7 cm) The Mayor Gallery, London AI MITSU Japan, 1907–1946 Work , 1941 Sumi ink 3 1 10 /8 x 7 /8 in. (26.4 x 18 cm) The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE Italy, 1880–1918, active France La Mandoline œillet et le bambou (Mandolin Carnation and Bamboo), c. 1915–17 Ink and collage on 3 pieces of paper 7 1 10 /8 x 8 /8 in. (27.5 x 20.9 cm) Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Purchase 1985 JEAN (BORN HANS) ARP Germany, 1886–1966, active France and Switzerland Untitled , c. 1918 Collage and mixed media 1 5 8 /4 x 11 /8 in. (21 x 29.5 cm) Mark Kelman, New York Untitled , 1930–33 Collage 1 5 6 /8 x 4 /8 in. (15.6 x 11.8 cm) Private collection Untitled , 1940 Collage and gouache 1 1 7 /4 x 9 /2 in. (18.4 x 24.1 cm) Private collection JOHN BANTING England, 1902–1972 Album of 12 Blueprints , 1931–32 Cyanotype 1 3 3 Varying in size from 7 3/4x 6 /4 in. (23.5 x 15.9 cm.) to 12 /4 x 10 /4 in. (32.4 x 27.3 cm) Private collection GEORGES BATAILLE France, 1897–1962 Untitled Drawings for Soleil Vitré , c. -

Minimalism and Cubism Introduction

MINIMALISM AND CUBISM INTRODUCTION Minimalism and Cubism are two genres of art that can be said to have grown from the seeds of abstract art. The works produced in both are far from imitation of reality, although deriving ideas from it. Both cubism and minimalism were a change from the traditional views of art in the time they were founded. Cubism brought a new interpretation of 2D imitationalism paintings by emphasising more on the skeleton of real-world forms rather than focusing on the subject from one viewpoint, whereas minimalism took a step further by making an entire change to the use of conventional materials testing the boundaries of what can be considered as art. Realism The change from Realism to Cubism is evident in the way the subjects are painted. In the Realism artwork we see a more realistic version of the Cubism human subjects, whereas the cubism artwork portrays a more shattered mirror version of the subject. Le Repas des Pauvres Alphonse Legros 1877 Minimalism From cubism we see the use of straight edges developed into the minimalistic artwork. Violin and Palette Georges Braque The use of colour too developed 1909 from monochromatic to colourful. There is also tends to be a lack of real world subjects in this genre. Hyena Stomp Frank Stella 1962 CUBISM It began in the early 1900s after Picasso’s creation of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” in 1907. The genre mainly consisted of paintings that followed a monochromatic palette to keep the viewer’s focus on the structure of the subject in the work In contrast to the growing movements at the time such as fauvism, expressionism, etc. -

A Thesis Submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

FROM ANCIENT GREECE TO SURREALISM: THE CHANGING FACES OF THE MINOTAUR A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brenton Pahl December, 2017 Thesis written by Brenton Pahl B.A., Cleveland State University, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by —————————————————— Marie Gasper-Hulvat, Ph.D., Advisor —————————————————— Marie Bukowski, M.F.A., Director, School of Art —————————————————— John Crawford-Spinelli, Ed.D., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………………………….……iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ………………………………………………………………………………..vii I. INTRODUCTION Mythology in Surrealism ………………………………………………………………………….1 The Minotaur Myth ………………………………………………………………………………..4 The Minotaur in Art History …………………………………………………..…………………..6 II. CHAPTER 1 Masson’s Entry into Surrealism ……………………..…………………………………..…….…10 The Splintering of Surrealism …………..…………………….…………………………….……13 La Corrida …………………………………………………………………………………….….15 III. CHAPTER 2 The Beginnings of Minotaure ……………………………………………………………………19 The Remaining Editions of Minotaure …………………………………………………………..23 IV. CHAPTER 3 Picasso’s Minotaur ……………………………………………………………..………….……..33 Minotauromachy …………………………………………………………………………………39 V. CHAPTER 4 Masson and the Minotaur …………………..…………………………………………………….42 Acephalé ………………………………………………………………………………………….43 The Return to the Minotaur ………………………………………………………………………46 Masson’s Second Surrealist Period …………………..………………………………………….48 VI. CONCLUSION -

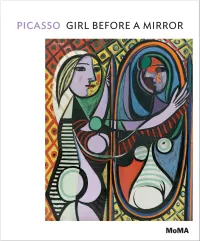

Picasso: Girl Before a Mirror

PICASSO GIRL BEFORE A MIRROR ANNE UMLAND THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK At some point on Wednesday, March 14, 1932, Pablo Picasso stepped back from his easel and took a long, hard look at the painting we know as Girl before a Mirror. Deciding there was nothing more he wanted to change or to add, he recorded the day, month, and year of completion on the back of the canvas and signed it on the front, in white paint, up in the picture’s top-left corner.1 Riotous in color and chockablock with pattern, this image of a young woman and her mirror reflection was finished toward the end of a grand series of can- vases the artist had begun in December 1931, three months before.2 Its jewel tones and compartmentalized composition, with discrete areas of luminous color bounded by lines, have prompted many viewers to compare its visual effect to that of stained glass or cloisonné enamel. To draw close to the painting and scrutinize its surface, however, is to discover that, unlike colored glass, Girl before a Mirror is densely opaque, rife with clotted passages and made up of multiple complex layers, evidence of its having been worked and reworked. The subject of this painting, too, is complex and filled with contradictory symbols. The art historian Robert Rosenblum memorably described the girl’s face, at left, a smoothly painted, delicately blushing pink-lavender profile com- bined with a heavily built-up, garishly colored yellow-and-red frontal view, as “a marvel of compression” containing within itself allusions to youth and old age, sun and moon, light and shadow, and “merging .