Babelstone: the Ogham Stones of the Isle Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

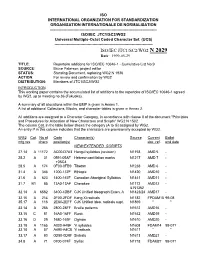

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

Celtiques, Conséquence

L’IMPOSTURE DE « L’ASTROLOGIE CELTIQUE » 1 par Peter Berresford Ellis Traduction par Philippe Camby Les fabrications de « zodiaques d’arbres » celtiques, conséquence directe de l’invention d’un « calendrier des arbres » par Robert Graves, sont devenues un obstacle presque insurmontable pour des études sérieuses sur l’astrologie réellement pratiquée dans les sociétés celtiques préchrétiennes. Depuis que Robert Graves, il y a cinquante ans, a publié La déesse blanche (The White Goddess, 1946 2), ses imitateurs ont bâti une véritable industrie éditoriale qui professe des opinions astrologiques erronées, basées sur des arguments faux. Quelques-uns ont même publié des ouvrages sur ce qu’ils nomment familièrement l’« astrologie celtique », fabriquant ainsi « un système astrologique » sans authenticité. Il n’entre pas dans mes habitudes de critiquer Robert Graves ou ses disciples. Poète et romancier, Graves est tout à fait admirable et son étude des mythes grecs (Greek Myths, 1955) est hautement appréciée. Il y a même beaucoup de choses précieuses dans La déesse blanche. Son travail a consisté en une tentative intéressante d’analyse anthropologique et mythologique ; il aurait pu en résulter, avec une assistance universitaire, un apport intéressant dans la ligne des œuvres de Joseph Campbell 3. Cependant, alors qu’il avait besoin de l’avis d’un maître réputé dans les recherches celtiques, et particulièrement dans le domaine de l’Ogham, il a refusé d’y recourir parce qu’il n’admettait pas les rigoureux concepts de cette discipline. « Chacun est un débutant dans le commerce ou le métier d’autrui 4 », c’est un vieux proverbe irlandais que j’ai souvent cité. -

Florida Native Plants Ogam

Florida Native Plants Ogam OBOD Ovate Gift Dana Wiyninger Starke, Florida USA July 29, 2012 Introduction Moving to a new region with completely different plants and climate, and having to manage a neglected forest meant I had to really learn about and examine the trees and plants on our property. (No relying on my previous knowledge of plants on the west coast.) Even with the subtropical climate, we paradoxically have many temperate east coast trees in north Florida. To make sense of it all in context of the Ogam, I had to seriously study and search to find the plants in my Florida Ogam. I often had to make more intuitive associations when an Ogam plant species wasn‟t found here. I had vivid impressions from the Ogam (and other) plants- I later used these to find my path through the many interpretations authors have offered. Personally, I use my own Florida correspondences when I see many of these plants every day; the impressions and messages are just part of my perceptions of the plants now. Since using my correspondences I‟m more aware of the varying time streams the plants experience and the spirits associated with them. I feel a conduit with the plants, and the resulting insights are particularly useful to me and relevant to changes going on in my life. Not quite formal divination, I receive guidance none the less. I feel there may be a healing practice in my future that will incorporate the Ogam, but that is yet to come. So, as enjoyable as it was, learning the basics of the Ogam wasn‟t easy for me. -

Download (1MB)

Quaintmere, Max (2018) Aspects of memory in medieval Irish literature. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/9026/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Aspects of Memory in Medieval Irish Literature Max Quaintmere MA, MSt (Oxon.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2017 Abstract This thesis explores a number of topics centred around the theme of memory in relation to medieval Irish literature roughly covering the period 600—1200 AD but considering, where necessary, material later than this date. Firstly, based on the current scholarship in memory studies focused on the Middle Ages, the relationship between medieval thought on memory in Ireland is compared with its broader European context. From this it becomes clear that Ireland, whilst sharing many parallels with European thought during the early Middle Ages based on a shared literary inheritance from the Christian and late-classical worlds, does not experience the same renaissance in memory theory that occurred in European universities from the thirteenth century onwards. -

Ogham-The-Druidic-Play

Ogham (A Druidic Play1) by Susa Morgan Black, Druid (OBOD) Characters: Celtic Deities: Name Description Suggested Prop or tool Nemetona NEH-MEH- Celtic Goddess of Sacred Robed in the colors of the TONA Groves and forests forest – greens and browns Duine Glas DOON-YEH - The Green Man Green foliage, Celtic torque GLAS Druid Fellowship: Name Description Suggested Prop or tool Druid Master of Ceremonies, Druid staff or shepherd’s dressed in white robe and crook; or scythe and gold tabard (or plain white mistletoe robe with no tabard) Ovate Seer; dressed in white robe Ogham cards in ogham and green tabard bowl, Druid wand Bards Poets, Musicians; dressed Harp or Zither; in white robe and blue Drum tabard Nymphs Dressed as fairies Fairy wands, flowers, etc. The Ogham Trees (in one of the traditional ogham orders, Beth Luis Fearn). Each tree should have a sign with their tree name printed in Gaelic and English, so that they can be easily found at the time of divination Name Description Suggested Prop or tool Beith (Birch) BEHTH A young, energetic maiden white shawl Luis (Rowan) LOOSH A witchy, sexy woman sheer red veil Fearn (Alder) FARN A strong determined man, a Building tools (perhaps a “bridge builder” hammer) Saille (Willow) SALL-YEH A mysterious lunar female Luminescent shimmering veil Nunn (Ash) NOON A stalwart guardian tree Spear Huathe (Hawthorn) HOO- The playful May Queen Green and white finery with AH a floral wreath Duir (Oak) DOO-OR Regal Male, Druid King of Oak staff, scepter, acorns the Woods Tinne (Holly) TCHEEN- Young male warrior -

Rune-Names: the Irish Connexion

Rune-names: the Irish connexion Alan Griffiths Introduction Runologists are justifiably sceptical when it comes to comparing anything ogamic with anything runic. Moltke was also justifiably sceptical when he said of attempts to explain rune-names that “We may safely relegate them to the world of fantasy” (1985: 37). While acknowledging such scepticism, this paper nonetheless dares not only to venture into the world of rune-names, but also to compare them with ogam- names. In so doing it risks confrontation with the long-nurtured view crystal- lized in Polomé’s contention concerning the rune-names recorded in manu- scripts that “It is fairly undeniable that the names they transmit to us appear to derive from a common source, which has enabled Wolfgang Krause to recon- struct a plausible early Germanic list...” (1991: 422). In the paper from which this sentence is taken Polomé reviews what might be called the pagan-cult thesis of rune-names, which he summarizes in the commonly accepted hypothesis that the names “are imbedded in the German concepts about the world of the gods, nature and man” (1991: 434). He also reiterates the idea, based on classical references to the Germans’ use of notae, that runes were employed for divi- nation and “in this context, they were ideographic, i.e. we deal with the so-called Begriffsrunen...” (1991: 435).1 But then he reminds us, albeit in a valedictory footnote: “It should be remembered that these names of runes do not occur in any document of pagan origin, nor in any source (either alphabetic listings [runica manuscripta] or runic poems) prior to the Carolingian Renaissance” (1991: 435, fn. -

Trees and Woodland Names in Irish Placenames John Mc Loughlina*

IRISH FORESTRY 2016, VOL. 73 Trees and woodland names in Irish placenames John Mc Loughlina* The names of a land show the heart of the race, They move on the tongue like the lilt of a song. You say the name and I see the place Drumbo, Dungannon, Annalong. John Hewitt Since trees are very visible in the landscape, it is not surprising that so many of our placenames have derived from trees and woods. Today, if a forest was to spring up everywhere there is a tree-associated name in a townland, the country would once more be clothed with an almost uninterrupted succession of forests. There are more than 60,000 townlands in Ireland and it is estimated that 13,000 or 20% are named after trees, collections of trees (e.g. grove) and the uses of trees. Prior to road signs, with which we are so familiar today, natural and manmade features were the only directional sources. Placenames have been evolving since the dawn of Irish civilisation when most of the country was heavily forested and trees had a prominent role in the economy. Trees provided raw materials, medicine, weapons, tools, charcoal, food (in the form of berries, nuts, fungi, fruit, wild animals, etc.), geographical markers as well as the basis for spirituality and wisdom. It is difficult for us today to interpret the origins of some of our placenames; they are derived from old Irish interspersed with Viking, Norman, and Medieval English influences, and in the north of the country Scots Gaelic also adds its influence. -

Language in Ancient Europe: an Introduction Roger D

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68495-8 - The Ancient Languages of Europe Edited by Roger D. Woodard Excerpt More information chapter 1 Language in ancient Europe: an introduction roger d. woodard The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong, indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothik and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family. Asiatick Researches 1:442–443 In recent years, these words of an English jurist, Sir William Jones, have been frequently quoted (at times in truncated form) in works dealing with Indo-European linguistic origins. And appropriately so. They are words of historic proportion, spoken in Calcutta, 2 February 1786, at a meeting of the Asiatick Society, an organization that Jones had founded soon after his arrival in India in 1783 (on Jones, see, inter alia, Edgerton 1967). If Jones was not the first scholar to recognize the genetic relatedness of languages (see, inter alia, the discussion in Mallory 1989:9–11) and if history has treated Jones with greater kindness than other pioneers of comparative linguistic investigation, the foundational remarks were his that produced sufficient awareness, garnered sufficient attention – sustained or recollected – to mark an identifiable beginning of the study of comparative linguistics and the study of that great language family of which Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Gothic, Celtic, and Old Persian are members – and are but a few of its members. -

Answers and Solutions

191 ANSWERS AND SOLUTIONS ~ds a column POEMS IN PRAISE OF ENGLISH PHONOLOGY Charles F. Hockett ment on arti lough need for 1. stop 2. spirant 3. labial, laminal, dorsal 4. lateral, retroflex, nasal 5. voiceless 6. voiceless 7. voiceless, obstruent 8. nasal but let I s 9. voicele s s 10. labial rench-Ian AN OLYMPIC QUIZ Darryl Francis ure Potenti Horrors of myopical, diplomacy, cephalodymia, polydemoniac, polysemantic, ecita1 of the polymicrobic, mycoplasmic, compliancy, cytoplasmic, microphysi cle on OuLiPo cal, polyschematic Lge example polymicroscope, cosmopolicy, lycopersicum, lycopodium/polycod ~y, hate-shy ium, polygamistic, cryptoglioma, hypokalemic, polypharmic, poly you ex-wise mathie, myelopathic, polyhemic, lipothymic polychromia, polychromin, polytrichum, polystichum, impolicy, lms, Profes mispolicy, compliably, myopically, pyromellitic, symptomical, :h Phonologyll cryptonemiales, polyatomic : a princess in .ins no bilabials polysomatic, polynomic, cypselomorphic, polymicrian, policymak er, microtypal, pyrometrical, polymeric, microcephal y /pyrochem ical, polycormic, polydromic, polymastic es of the is sue ge as this can spatilomancy, cyps eliform, compre s sively, myeloplastic, polysomic, , and I try to polycrotism, polycentrism, polymetameric, polymythic, complicity, ~ar in rough compositely, polyonymic llC e of printing , to the problem. PRIMER TIME Ralph G. Beaman the se copie s however, if 'two letter s, T and A, are used in this alphabet primer to form the ed. (Don't tliree-Ietter words TAA, TAB, TAC, etc. Two imperfect words are TAFe and TAQlid. -- Adventuret! KlCKSHAWS Philip M. Cohen mprehensive Heful study. Jabberwocky: The vicar Bwigs chilled bubbly in the parish too. litd in defining If you try this with II Jabberwocky" you'll find it much less ::annot stomach; amenable, but some changes are possible. -

Auraicept Na Néces: a Diachronic Study

Auraicept na nÉces: A Diachronic Study With an Edition from The Book of Uí Mhaine Nicolai Egjar Engesland A dissertation submitted for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor The 20th of October 2020 Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo τῳ φωτί τῆς οἰκίας Foreword First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Mikael Males at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies at the University of Oslo for his untiring support and crucial input to the project at all stages. His enthusiasm for the field is unmatched. Der var intet valg, kun fremad, ordren ville lyde: døden eller Grønlands vestkyst. Secondly, I would like to thank Jan Erik Rekdal for having co-supervised the project and for having introduced me to the fascinating field of Irish philology and to Conamara. I would like to thank Pádraic Moran for valuable help with the evaluation of my work this spring and for useful feedback also during the conference on the dating of Old Norse and Celtic texts here in Oslo and on my visit to the National University of Ireland Galway last autumn. A number of improvements to the text and to the argumentation are due to his criticism. The community at NUI Galway has been very welcoming and I would like to show my gratitude to Michael Clarke and Clodagh Downey for accommodating us during our trip. Clarke also provided me with profitable feedback during the initial part of my work and has been a steady source of inspiration at conferences and workshops both in Ireland and in Norway.