Architectural Site Intimacy Nurturing the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Build the USS CONSTITUTION the World’S Oldest Commissioned Naval Vessel Afloat 12 Build the USS CONSTITUTION Contents STAGE PAGE 111 Sails 245

Build the USS CONSTITUTION The world’s oldest commissioned naval vessel afloat 12 Build the USS CONSTITUTION Contents STAGE PAGE 111 Sails 245 112 Sails and flags 247 113 Sails 249 114 Sails 251 115 Sails 253 116 Sails 255 117 Sails 257 118 Sails 259 119 Sails 261 120 Sails 263 Editorial and design by Continuo Creative, 39-41 North Road, London N7 9DP. Published in the UK by De Agostini UK Ltd, Battersea Studios 2, 82 Silverthorne Road, London SW8 3HE. Published in the USA by De Agostini Publishing USA, Inc.,121 E. Calhoun Street, Woodstock, IL 60098. All rights reserved © 2017 Warning: Not suitable for children under the age of 14. This product is not a toy and is not designed or intended for use in play. Items may vary from those shown. USS CONSTITUTION STAGE: 111 C 79 Sails 75 68 V3. Fore topmast staysail V4. Main topmast staysail 57 V4 V3 111C Following the plan, attach the four yards (57, 68, 75 and 79) to the front of the foremast. 111D Now prepare the three sections of the mainmast, following the plan. The mainmast (81) with fittings and top, the main topmast (106) and the main topgallant mast (112) following the same process as with the foremast. 111A Retrieve the spritsail A D yard (20) and secure it to the 81 bowsprit with the parrel (23). Tie the parrel to the yard, then pass it over the bowsprit and secure the free end to the yard. 20 112 106 B E 64 111B Retrieve the foremast yards (57, 68, 75 and 79) prepared in Stage 110 and paint them with wood stain. -

President's Corner Family Fun

UKRAINIAN A MERICAN N AUTICAL A SSOCIATION INC. Volume 4, Issue 4 U.A.N.A.I. NEWS November, 2007 Family Fun Day President's Corner - Marusia Antoniw – David Sembrot, U.A.N.A.I. President In late July, fifteen UANAI members and guests gathered on the shores of Hello everyone! What an exciting summer & early fall picturesque Marsh Creek Lake State Park for the UANAI’s first annual season sailing season we have had. We completed Family Fun Day. The outing included two of the youngest participants to our first family day sailing event at Marsh Creek Lake in ever join a UANAI event! Downingtown, PA; planned an exciting off-season trip to Greece for May of 2008 and had many members use this season to increase their sailing knowledge through classes and independent reading. All of these items are within the goals of the club to build activities around a diversity of members who have varying knowledge and skill levels and to provide everyone an opportunity to both enjoy and learn more about sailing and boating. As always, I welcome everyone to reach out to me to Marsh Creak Lake State Park, Chester County / Southeastern Pennsylvania. provide feedback, opinions and questions about what they would like the club to tackle. (215) 680-7787 The weather was warm, the company delightful and although the breezes were light, it was one of the first events where Please take your time in SPECIAL POINTS all participants could relax as a group. enjoying this fall a newsletter and don't Beautiful Marsh Creek Lake has wonderful forget to check out the facilities with many options for family boating many useful and >Do you know the parts of fun. -

Part 19 Mizzen Topsail

Part 19 Part 19, similar to part 18, we will be moving up the masts to the next level to install and rig the Topmast yards and sails. When building the masts, I had put the long pole on the top of the mizzen mast and had just assumed that I would be installing a mizzen topgallant, but this was not to be. So the mizzen topsail is as high as I go. You will see in some of the pictures I rigged a mizzen topgallant fore stay to “fill” the space. As before, I re-sequenced the steps to merge the rigging of the sails with the basic rigging. This chapter goes hand in hand with chapter 23 to marry the yards and sails together. I have included the sequencing for the topsails below. (Most of the photos in this chapter were taken after the fact and not during the assembly work) Mizzen Topsail Atalanta Mizzen Topsail Installation Sequence 1770’s (Period 1760 – 1800) 19.1 Make Topsail yard Sling cleat Stop cleat 19.2 Yard horses and stirrups (4) 19.3 Yard sheet blocks (2) 19.4 Yard clueline blocks (2) 19.5 Yard brace pendants (2) 19.8 Yard lift blocks (2) 23.1 Sew Sail Reef Points Bend sail – (carp. glue 60/40 solution) Lace Sail to yard 19.7 Yard tye and halliards 19.9 Yard lifts 19.10 braces 19.11 Vangs 23.16 sail cluelines (2) 23.17 sail buntlines (2) 23.18 sail bowlines and bridles(2) 23.19 sail sheets (2) XX Bend sail (2nd time) At this point all tackle; sail and sail rigging are attached to the yard and ready to install. -

Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions Historical Musings from Salem Maritime NHS

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions Historical Musings from Salem Maritime NHS The First Three Years Volume VII, number 3 August 2005 On the cover: a schooner, the most popular vessel in Salem in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Schooners have at least two masts, and sometimes more, all rigged fore-and-aft (along the line of the keel from the front to the back of the vessel). Some schooners also carry a topsail on the foremast that is rigged on a yard hung square, or perpendicular, to the keel. 2 Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions The U.S. Customs Service When the United States Customs Service was formed in 1789, the agency was designed to uniformly enforce and expedite the process of collecting revenue and assembling statistical data for the newly established United States govern- ment. Customs revenues provided the primary source of funding until the ad- vent of the income tax. One critical aspect of the Customs process was the regulation of maritime commerce. On August 7, 1789, “An Act for registering and clearing Vessels, regulating the Coasting Trade, and for other Purposes” was approved by President Washing- ton.1 This act addressed the documentation of vessels and enumerated the con- ditions, laws, and penalties by which the business of shipping was to be con- ducted. Certificates of registration were issued by Collectors of Customs to American-owned vessels sailing from United States ports to foreign destina- tions. These documents recorded the basic data of ownership, length, breadth, and depth of hold, builder, age, number of masts and decks, descriptive details, and most importantly, the tonnage of each vessel. -

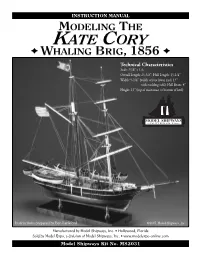

Kate Cory Instruction Book

Kate Cory_instructions.qxd 1/10/07 12:20 PM Page 1 INSTRUCTION MANUAL MODELING THE KATE CORY ! WHALING BRIG, 1856 ! Technical Characteristics Scale: 3/16" = 1 ft. Overall Length: 23-5/8"; Hull Length: 15-1/4" Width: 9-1/4" (width of fore lower yard, 13" with studding sails); Hull Beam: 4" Height: 19" (top of main mast to bottom of keel) Instructions prepared by Ben Lankford ©2007, Model Shipways, Inc. Manufactured by Model Shipways, Inc. • Hollywood, Florida Sold by Model Expo, a division of Model Shipways, Inc. • www.modelexpo-online.com Model Shipways Kit No. MS2031 Kate Cory_instructions.qxd 1/10/07 12:20 PM Page 2 HISTORYHISTORY Throughout the middle of the 19th century, activities in the Atlantic whale fishery were carried out in small fore-and-aft schooners and brigs. The latter are hermaphrodite brigs, or “half-brigs”, or simply “brigs” to use the jargon of laconic whalemen. Kate Cory was built in 1856 by Frank Sisson and Eli Allen in Westport Point, Massachusetts for Alexander H. Cory, one of the lead- ing merchants of that community. The ship was named after Alexander’s daughter. Registered at 132 tons net, Kate Cory was 75' 6" in length between perpendiculars, 9' 1-1/2" depth, and had a beam of 22' 1". The last large vessel to be built within the difficult confines of that port, she was also one of the last small whalers to be built specifically for her trade; most of the later whaling brigs and schooners were converted freighters or fishermen. While originally rigged as a schooner, Kate Cory was converted to a brig in 1858, this rig affording steadier motion in heavy seas or while cutting-in whales, not to mention saving much wear and costly repair to spars, sails and rigging. -

Jack London the Mutiny of the « Elsinore »

JACK LONDON THE MUTINY OF THE « ELSINORE » 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted THE MUTINY OF THE ELSINORE by Jack London CHAPTER I From the first the voyage was going wrong. Routed out of my hotel on a bitter March morning, I had crossed Baltimore and reached the pier- end precisely on time. At nine o'clock the tug was to have taken me down the bay and put me on board the Elsinore, and with growing irritation I sat frozen inside my taxicab and waited. On the seat, outside, the driver and Wada sat hunched in a temperature perhaps half a degree colder than mine. And there was no tug. Possum, the fox-terrier puppy Galbraith had so inconsiderately foisted upon me, whimpered and shivered on my lap inside my greatcoat and under the fur robe. But he would not settle down. Continually he whimpered and clawed and struggled to get out. And, once out and bitten by the cold, with equal insistence he whimpered and clawed to get back. His unceasing plaint and movement was anything but sedative to my jangled nerves. In the first place I was uninterested in the brute. He meant nothing to me. I did not know him. Time and again, as I drearily waited, I was on the verge of giving him to the driver. Once, when two little girls--evidently the wharfinger's daughters-- went by, my hand reached out to the door to open it so that I might call to them and present them with the puling little wretch. -

Logbook of the United States Frigate Constitution Charles Stewart, Commander December 31, 1813 - April 3

TRANSCRIPTION OF Logbook of The United States Frigate Constitution Charles Stewart, Commander December 31, 1813 - April 3. 1814 December 18, 1814 - May 16, 1815 Original logbooks available at “Logbook of the U.S.S. Constitution”, Volume 4, December 31, 1813 – April 3, 1814, and December 18, 1814 – May 16, 1815. Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group 24. (Microform publication M1030, T508, Roll 1, Target 3) National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. © 2018 USS Constitution Museum | usscm.org H. K. F. Courses. Winds. Friday, December 31. 1813. 1 NNE Commences with clear weather and strong breezes from the Westwards. At 1 P.M unmoored Ship. At 3 got under way. 2 At half past 4 past Boston light. At three quarters past 4 discharged the Pilot. At 5 Boston light bore W. by. N. ½. N. 3 distant five miles. At 5 set top-gallant sails. At 7 took in top gallant sails. At half past 7 Thatcher’s Island light bore 4 N.W. by W. distant two leagues. At three quarters past 7 took two reefs in the Mizen top-sail. At 9 Set Fore and Main top gallant sails. At half past 9 set the Spanker; fresh breezes and cloudy weather. At half past 11 brailed up the 5 spanker. At midnight took in top gallant sails; fresh breezes and cloudy. At half past 12 A.M. set the Main top gallant 6 10 4 N.E. N.W. sails. At 2 took in main top gallant sail. At 4 turned the reefs out of the top sail and set Fore and Main top gallant sails. -

United States National Museum

CL v'^ ^K\^ XxxV ^ U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 127 PL. I SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 127 CATALOGUE OF THE WATERCRAFT COLLECTION IN THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM COMPILED AND EDITED BY CARL W. MITMAN Curator, Divisions of Mineral and Mechanical Technology ;?rtyNc:*? tR^;# WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADVERTISEMENT. The .scientific publications of the United States National Museum consist of two series, the Proceedings and the Bulletins. The Proceedings^ the first volume of which was issued in 1878, are intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original and usually brief, papers based on the collections of the National Museum, presenting newly acquired facts in zoology, geology, and anthropology, including descriptions of new forms of animals and revisions of limited groups. One or two volumes are issued annu- ally and distributed to libraries and scientific organizations. A limited number of copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, is dis- tributed to specialists and others interested in the different subjects as soon as printed. The date of publication is recorded in the table of contents of the volume. The Bulletins^ the first of which was issued in 1875, consist of a series of separate publications comprising chiefly monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occa- sionally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, and catalogues of type-specimens, special collections, etc. The majority of the volumes are octavos, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which large plates were regarded as indispensable. Since 1902 a series of octavo volumes containing papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum, and known as the Con- trihutions from the National Herharium.^ has been published as bulletins. -

Tall Ships Fabrics

Tall Ships Fabrics Demands placed on sailcloth used in sails for Tall Ships fabrics are so tightly woven that they can Tall Ships, whether they are square, gaff or marconi be finished with nearly no resin. During the finishing rigged, are among the most extreme in the world process the cloth is heat-set at high temperature of sailing. The sails must withstand huge forces that to further tighen the weave. As a result, Challenge only a heavy, stable tall ship can generate. To this Tall Ships fabrics have good bias stability for their end, Challenge has developed its own fibers and large yarn construction, but at the same time have fabrics to ensure the best UV resistance, tear strength, a soft hand that enables easy handling. abrasion resistance and tensile breaking strength. Challenge has made fabric for hundreds of Tall Ships and Challenge carefully tests all of cloth to ensure that it Schooners for over twenty-five years. Some Tall Ships whose meets the stringent standards of the most demanding sails have been made of Challenge Tall Ships Fabrics include Star Clipper, Royal Clipper, Libertad, Cisne Branco, Esmeralda, projects a sailmaker may have. Please see below Gloria, Guayas, Cuauhtémoc, Capitán Miranda, Simón Bolívar for tables and graphs of these specifications. and Juan Sebastián de Elcano (pictured below). High-Tech Woven Sailcloth USA – CT USA – CAL Australia France Germany Italy Norway United Kingdom 860 871 8030 949 722 7448 (2) 9832 7000 (0) 5468 78480 (0) 2654 987718 0 (0) 187630603 67 10 25 60 (0) 1489 581 696 Tall Ships Fabrics Common Applications While every sailmaker and ship captain will have their own opinions regarding which weight of cloth to use for which sail based on their own experiences, Challenge can provide general guidance for how their Tall Ships Fabrics can be used. -

United States National Museum, Washington, D

GREAT INTERNATIONAL FISHERIES EXHIBITION. LONDON, 1883. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. I. CATALOGUE OF THE COLLECTION ILLUSTRATING THE FISHING VESSELS AND BOATS, AND THEIR EQUIPMENT; THE ECONOMIC CONDITION OF FISHERMEN; ANGLERS' OUTFITS, ETC. CAPTAIN J. W. COLLINS, Assistant, U. S. Fish Commission. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1 8 S 4 . 645 : — TABLE OF CONTENTS. A. Introduction. Page. Statistics and history of fishing vessels 7 Statistics and history of fishing boats 12 Apparatus accessory to rigging fishing vessels 14 Fishermen and their apparel 19 Food, medicine, and shelter 21 Fishermen's log-books 22 Fishermen's widows and orphans aid societies 22 B.—Fishing craft. VESSELS. Rigged models 1. Fishing steamers 26 2. Fishing ketches 26 3. Fishing schooners 27 Builders' models: 4. Fishing schooners . 37 BOATS. 5. Sloop, cutter, and cat-rigged square-stern boats 45 6. Schooner-rigged square-stern boats 49 7. Square-stern row-boats 50 8. Sharp-stern round-bottom boats 50 9. Flat-bottom boats 54 10. Portable boats 58 11. Sportsmen's boats 61 12. Bark canoes 62 13. Skin boats and canoes 62 14. Dug-outs 63 SKETCHES AND PHOTOGRAPHS OF VESSELS AND BOATS. 15. General views of fishing fleets 65 16. Fishing steamers 66 17. Square-rigged vessels 67 18. Fishing schooners 67 Pinkeys 67 Mackerel-fishing vessels 66 Cod-fishing vessels 70 Fresh-halibut vessels „ 71 Herring catchers 72 Fishing schooners, general 72 [3] 647 — 648 CONTENTS. [4] 19. Sloops 73 20. Cutters 73 21. Quoddy and Block Island boats , 74 22. Seine-boats 74 23; Sharpies... , ... , , 74 24. Dories 75 25. -

Life on Board A.Merican Clipper Ships

-vC %g Lifeon Board A.merican Clipper Ships byCharles R. Schultz PublishedbyTexas AbM UniversitySea Grant College Program Co~ght@ 1983 by TexasA&M UnioersitySea Grant CollegeProgram TAMU-SG-83-40? 3M January1983 NA81AA-D00092 ET/C-31 Additionalcopies available from: Marine InformationService SeaGrant CollegeProgram TexasA&M University CollegeStation, Texas 77843-4115 $1.00 Dr. CharlesR, Schuitz,whose interest in maritime history has been the impetusfor consider- able researchin thisfi eld, urn Keeperof kfanuscripts and Librarian at hfysticSeaport in Con- necticut for eightyears before he was appointed UniversityArchivist at TexasASM Universityin 1971. Virtually Irom the beginning of shipbuilding in Ameri- to be referredto as"Baltimore clippers," ca,American ship builders have been able to construct Bythe mid 19thCentury a numberof thingshad hap- fastsailing vessels, American craftsmen have consistently penedthat made the famous American clipper ships pos- demonstratedthe abilityto learnfrom eachother, as well sible. When the Black Ball Line wis established in 1818 astheir foreigncounterparts. They have done remarkably and set a regularschedule for packet ships sailing be- well in choosingonly the bestdesign attributes of those tween New York and Europe, it quickly took over the from whom theyhave copied. The developmentof the profitable passengertrafFic and much of the most lucra- famousclipper ships during the 1850's exemplifies the tive lreightbusiness on the NorthAtlantic, It quicklybe- apexof suchdevelopments. cameclear that the fastestships would attractthe most Duringthe colonialperiod of U.S.history, American passengersas weil asthe freightwhich paidthe highest merchantsand their shipswere legallybarred Irom most rates.This created a demandfor shipswhich could sail of thelucrative trades. The only way they could operate fasterthan those which had been built in previous in somegeographical areas or tradein sometypes of decades. -

Tall Ship Rigs

Rules for Classification and Construction I Ship Technology 4 Rigging Technology 1 Tall Ship Rigs Edition 1997 The following Rules come into force on May 1st, 1997 Germanischer Lloyd Aktiengesellschaft Head Office Vorsetzen 35, 20459 Hamburg, Germany Phone: +49 40 36149-0 Fax: +49 40 36149-200 [email protected] www.gl-group.com "General Terms and Conditions" of the respective latest edition will be applicable (see Rules for Classification and Construction, I - Ship Technology, Part 0 - Classification and Surveys). Reproduction by printing or photostatic means is only permissible with the consent of Germanischer Lloyd Aktiengesellschaft. Published by: Germanischer Lloyd Aktiengesellschaft, Hamburg Printed by: Gebrüder Braasch GmbH, Hamburg I - Part 4 Table of Contents Chapter 1 GL 1997 Page 3 Table of Contents Section 1 Rules for the Masting and Rigging of Sailing Ships (Traditionell Rigs) A. General ....................................................................................................................................... 1- 1 B. Definitions .................................................................................................................................. 1- 1 C. Dimensioning of Masts, Topmasts, Yards, Booms and Bowsprits ............................................. 1- 3 D. Standing Rigging ........................................................................................................................ 1- 9 E. Miscellaneous ............................................................................................................................