UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

History of Hula the Origins of Hula Are Contained in Many Legends. One Story Describes the Adventures of Hi'iaka, Who Danced To

History of Hula The origins of hula are contained in many legends. One story describes the adventures of Hi'iaka, who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele and there she created Hula. This Hi'iaka story provides the basic foundation for many present-day dances. As late as the early twentieth century, ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice. Teachers and students were dedicated to Laka, goddess of the hula, and appropriate offerings were made regularly. In ancient Hawaii, a time when a written language did not exist, hula and its chants played an important role in keeping history, genealogy, mythology and culture alive. With each movement – a hand gesture, step of foot, swaying of hips – a story would unfold. Through the hula, the Native Hawaiians were connected with their land and their gods. The hula was danced for protocol and social enjoyment. The songs and chants of the hula preserved Hawaii’s history and culture. When the missionaries arrived and brought Christianity, Queen Ka’ahumanu converted and deemed Hula a pagan ritual, banning it in 1830 and for many years with both Ōlelo Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian language, and Hula being suppressed or banned, the knowledge, tradition and culture of Hawai’i suffered greatly. It wasn’t until King David Kalakaua came to the throne in 1874 that Hawaiian cultural traditions were restored. Public performances of hula flourished and by the early 1900s, the hula had evolved and adapted to fit the desires of tourists and global expectations. With tourism, cabaret acts, Hollywood and the King himself, Elvis, Hula experienced a great transition to the Hula that many people imagine today. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Mast Furling Installation Guide

NORTH SAILS MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE Congratulations on purchasing your new North Mast Furling Mainsail. This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots. Step 1 Unpack your Sail Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later. Step 2 Attach the Mainsail Tack Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs. NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide. Step 2 www.northsails.com Step 3 Attach the Mainsail Clew Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. -

ICTM Study Group on Musics of Oceania Circular No. 16 New

ICTM Study Group on Musics of Oceania 17 April 1989 Circular No. 16 New Member We welcome Dr. Cynthia B. Sajnovsky to our Study Group. Please note her address on page 3 of this Circular and add it to the list of members distributed with Circular No. 15. ICTM Meeting in Schladming, Austria, 23-20 July 1989 So far, only Rossen has expressed the hope that members of our Study Group can get together during this World Conference. Of course, Christensen will attend in his capacity of Secretary General and Trimillos plans to attend in his capacity as member of the Executive Board. If other members do plan to participate/attend and would like to meet informally, I suggest you contact one of these three (I do not plan to attend). Other Forthcoming Events of Potential Interest to Members The 4th International Symposium of the Pacific Arts Association is to be held in Honolulu, 6-12 August 1989. (The sponsors are the Honolulu Academy of Arts, Bishop Museum, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, East-West Center, Hawaii Museums Association, Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program, Center for Pacific Islands Studies of the University of Hawaii, and Hawaii Loa College.) Reeves (now Helen Reeves Lawrence--congratulations, Helen!) and two other ICTM-SGMO members have expressed interest in an informal gathering with other members of our Study Group who may attend. The conference, titled "Artistic Heritage in a Changing Pacific," is clearly within our sphere of interests--especially the section on "Performing Arts." The other sections are "Role of the Museum in a Changing Pacific" (chaired by Kaeppler), "Visual Arts," and "The Future of Pacific Arts." The section on the performing arts is co-chaired by Moulin and Faustina Rehurer (Director of the Belau Museum). -

(1974) Isles of the Pacific

ISLES OF THE PACIFIC- I The Coming of the Polynesians By KENNETH P. EMORY, Ph.D. HE ISLES of the South Seas bathed in warm sunlight in the midst of the vast Pacific-were Tsurprise enough to their European discoverers. But more astonishingly, they were inhabited! And the tall, soft featured, lightly clad people who greet ed the Europeans possessed graces they could only admire, and skills at which they could but wonder. How had these brown-skinned peo ple reached the many far-flung islands of Polynesia? When? And whence had they come? The mystery lingered for centuries. Not until 1920-the year I joined the staff of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu-was a concerted search for answers launched, with the First Pan-Pacific Scientific Conference, held in the Hawaiian capital. In subsequent years scientists fanned out over the Pacific to salvage whatever knowledge of their past the Polynesians retained. The field was vast, for Polynesia sprawls in a huge triangle, from Hawaii in the north to Easter Island in the southeast to New Zealand in the southwest. I have taken part in many of these expe Nomads of the wind, shipmates drop sail ditions from Mangareva to outlying Ka as they approach Satawal in the central pingamarangi, some 5,000 miles away Carolines. The past of their seafaring and beyond the Polynesian Triangle. ancestors, long clouded by mystery and After the Tenth Pacific Science Con gress in 1961, scientists from New 732 NICHOLAS DEVORE Ill legend, now comes dramatically to light author, dean of Polynesian archeologists, after more than half a century of research. -

North Topsail Beach 2020 Audit (Municipalities Mi-P 6/30/20 2020

TOWN OF NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA Report of Audit For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Nature’s Tranquil Beauty TOWN OF NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA Table of Contents Page FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report ............................................................................................................... 6 Management’s Discussion and Analysis ................................................................................................ 9 Basic Financial Statements Government‐wide Financial Statements: Statement of Net Position .............................................................................................................. 18 Statement of Activities .................................................................................................................... 20 Fund Financial Statements: Balance Sheet – Governmental Funds ........................................................................................... 22 Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Net Position ........................................................................................................................................ 23 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances – Governmental Funds ............................................................................................................................................ 24 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental -

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: a Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Compiled and Edited by James P. Kauahikaua and Janet L. Babb Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 First release: 2017 Revised: June 2017 (ver. 1.1) For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kauahikaua, J.P., and Babb, J.L., comps. and eds., Conversing with Pelehonuamea—A workshop combining 1,000+ years of traditional Hawaiian knowledge with 200 years of scientific thought on Kīlauea volcanism (ver. -

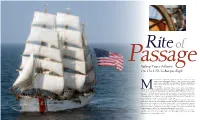

Sailing Trans-Atlantic on the USCG Barque Eagle

PassageRite of Sailing Trans-Atlantic On The USCG Barque Eagle odern life is complicated. I needed a car, a bus, a train and a taxi to get to my square-rigger. When no cabs could be had, a young police officer offered me a lift. Musing on my last conveyance in such a vehicle, I thought, My, how a touch of gray can change your circumstances. It was May 6, and I had come to New London, Connecticut, to join the Coast Guard training barque Eagle to sail her to Dublin, Ireland. A snotty, wet Measterly met me at the pier, speaking more of March than May. The spires of New Lon- don and the I-95 bridge jutted from the murk, and a portion of a nuclear submarine was discernible across the Thames River at General Dynamics Electric Boat. It was a day for sitting beside a wood stove, not for going to sea, but here I was, and somehow it seemed altogether fitting for going aboard a sailing ship. The next morning was organized chaos. Cadets lugged sea bags aboard. Human chains passed stores across the gangway and down into the deepest recesses of the ship. Station bills were posted and duties disseminated. I met my shipmates in passing and in passageways. Boatswain Aaron Stapleton instructed me in the use of a climbing harness and then escorted me — and the mayor of New London — up the foremast. By completing this evolution, I was qualified in the future to work aloft. Once stowed for sea, all hands mustered amidships. -

The Making of a Short Film About George Helm

‘Apelila (April) 2020 | Vol. 37, No. 04 Hawaiian Soul The Making of a Short Film About George Helm Kolea Fukumitsu portrays George Helm in ‘Äina Paikai's new film, Hawaiian Soul. - Photo: Courtesy - - Ha‘awina ‘olelo ‘oiwi: Learn Hawaiian Ho‘olako ‘ia e Ha‘alilio Solomon - Kaha Ki‘i ‘ia e Dannii Yarbrough - When talking about actions in ‘o lelo Hawai‘i, think about if the action is complete, ongoing, or - reoccuring frequently. We will discuss how Verb Markers are used in ‘o lelo hawai‘i to illustrate the completeness of actions. E (verb) ana - actions that are incomplete and not occurring now Ke (verb) nei - actions that are incomplete and occurring now no verb markers - actions that are habitual and recurring Ua (verb) - actions that are complete and no longer occurring Use the information above to decide which verb markers are appropriate to complete each pepeke painu (verb sentence) below. Depending on which verb marker you use, both blanks, one blanks, or neither blank will be filled. - - - - - - - - - I ka la i nehinei I keia manawa ‘a no I ka la ‘apo po I na la a pau Yesterday At this moment Tomorrow Everyday - - - - - - - I ka la i nehinei, I kEia manawa ‘a no, I ka la ‘apo po, lele - - I na la a pau, inu ‘ai ka ‘amakihi i ka mele ka ‘amakihi i ka ka ‘amakihi i ke ka ‘amakihi i ka wai. mai‘a. nahele. awakea. - E ho‘i hou mai i ke-ia mahina a‘e! Be sure to visit us again next month for a new ha‘awina ‘o-lelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language lesson)! Follow us: /kawaiolanews | /kawaiolanews | Fan us: /kawaiolanews ‘O¯LELO A KA POUHANA ‘apelila2020 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO WE ARE STORYTELLERS mo‘olelo n. -

(Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai'i Agency A

He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) By April L. Farnham A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Committee Members: Dr. Michelle Jolly, Chair Dr. Margaret Purser Dr. Robert Chase Date: December 13, 2019 i Copyright 2019 By April L. Farnham ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master’s Thesis Permission to reproduce this thesis in its entirety must be obtained from me. Date: December 13, 2019 April L. Farnham Signature iii He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) Thesis by April L. Farnham ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the ways in which working-class Kānaka Hawai’i (Hawaiian) immigrants in the nineteenth century repurposed and repackaged precontact Hawai’i strategies of accommodation and resistance in their migration towards North America and particularly within California. The arrival of European naturalists, American missionaries, and foreign merchants in the Hawaiian Islands is frequently attributed for triggering this diaspora. However, little has been written about why Hawaiian immigrants themselves chose to migrate eastward across the Pacific or their reasons for permanent settlement in California. Like the ali’i on the Islands, Hawaiian commoners in the diaspora exercised agency in their accommodation and resistance to Pacific imperialism and colonialism as well. Blending labor history, religious history, and anthropology, this thesis adopts an interdisciplinary and ethnohistorical approach that utilizes Hawaiian-language newspapers, American missionary letters, and oral histories from California’s indigenous peoples. -

No. 24 Mormon Pacific Historical Society

Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings 24th Annual Conference October 17-18th 2003 (Held at ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel in Honolulu) ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel (circa 1890’s) Built by Elder Matthew Noall Dedicated April 29, 1888 (attended by King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani) 1 Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2003 Conference Proceedings October 17-18, 2003 Auwaiolimu (Honolulu) Chapel Significant LDS Historical Sites on Windward Oahu……………………………….1 Lukewarm in Paradise: A Mormon Poi Dog Political Journalist’s Journey ……..11 into Hawaii Politics Alf Pratte Musings of an Old “Pol” ………………………………………………………………32 Cecil Heftel World War Two in Hawaii: A watershed ……………………………………………36 Mark James It all Started with Basketball ………………………………………………………….60 Adney Komatsu Mormon Influences on the Waikiki entertainment Scene …………………………..62 Ishmael Stagner My Life in Music ……………………………………………………………………….72 James “Jimmy” Mo’ikeha King’s Falls (afternoon fieldtrip) ……………………………………………………….75 LDS Historical Sites (Windward Oahu) 2 Pounders Beach, Laie (narration by Wylie Swapp) Pier Pilings at Pounders Beach (Courtesy Mark James) Aloha …… there are so many notable historians in this group, but let me tell you a bit about this area that I know about, things that I’ve heard and read about. The pilings that are out there, that you have seen every time you have come here to this beach, are left over from the original pier that was built when the plantation was organized. They were out here in this remote area and they needed to get the sugar to market, and so that was built in order to get the sugar, and whatever else they were growing, to Honolulu to the markets. These (pilings) have been here ever since.