Sailing Course Materials Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Specifications and Measurements Amended July 2012 Electronic Version July 2012 (In the Event of Discrepancies, the Handbook Hardcopy Takes Precedence) 1

By-Law 3 Specifications and Measurements Amended July 2012 Electronic version July 2012 (In the event of discrepancies, the Handbook hardcopy takes precedence) 1. Objectives 1.1. The Objectives of By-Law 3, Specifications and Measurements, are: i. to define a DS class yacht which is eligible to participate in all Association- sanctioned events. ii. to regulate the one-design character of the DS class yacht. iii. to guide DS owners. Association members, and other sailors who wish to participate in Association-sanctioned events. iv. to provide a uniform set of guidelines, to maintain fairness and high quality events for DS one-design class racing, in which race results are mainly determined by sailing skill, teamwork, and seamanship of the crew. 2. Jurisdiction 2.1. This By-Law regulates all sanctioned DS one-design racing events. All DS class yachts competing in such events shall conform to the contents of this By-Law. Authority to modify this By-Law is as specified in the Association Constitution. 2.2. Interpretations of the By-Laws by any measurer may be applied as follows: (i) give informal advice to any class Member, (ii) to complete a Measurement Certificate, or (iii) to advise a Protest Committee. The Class Measurer shall have the greatest authority to interpret the contents of the By-Laws, and shall always have the authority to modify a previous action by any measurer. Only the Class Measurer may issue Waivers per Paragraph 3.3 below. Except for the provisions of Paragraph 11 below, only the class Measurer may add or remove an Attachment to a Measurement Certificate. -

King Tides King Tides Are Simply the Very Highest Tides of the Year

Volume XVIII, No. 07 JULY 2017 July 2017 King Tides King Tides are simply the very highest tides of the year. They are naturally occurring, predictable events associated with the alignment of the moon and the sun orbits to maximize the gravitational pull on the earth. In Hawai‘i these typically occur in the summer months (June and July and December and January. Continued on next page Inside this issue: July 2017 King Tide Attachments “100 years of lifeguarding on O‘ahu” Mangoes return for the 9th annual “Mangoes at the Moana” at Over the Rainbow at Hilton Hawaiian Village The Moana Surfrider, A Westin Resort Spa Makana presented to Hokulea crew on world-circling Renowned artist brings dazzling Hawaii wildlife art event to Malama Honua Voyage on display at Hawaii Convention Center The Moana Surfrider, A Westin Eesort & Spa Four new merchants announced at Pualeilani Atrium Shops WBW celebrating a decade of dining and distinction 47th Annual ‘Ukulele Festival Royal Hawaiian Center news, promotions, entertainment and events Top of Waikiki announces July Special Outrigger Resorts & Henry Kapono present Artist to Artist Concert Series Ron Richter named Dir of Food & Bev at Sheraton Waikīkī Dukes Lane Market & Eatery news Upcoming Ala Moana Centerstage shows Top of Waikīkī July Specials Honolulu Zoo Society’s Wildest Show in Town Sheraton Princess Kaiulani – Hot News International Market Place welcomes Phillip Lim boutique The Surfjack presents – July at the Swim Club Waikīkī Hula Show at the Kūhiō Beach Hula Mound WBW Nā Mele No Nā Pua Sunday concerts WBW July Entertainment & Activities Kani Ka Pila July Entertainment calendar WIA 2017 Ho‘owehiwehi Awards . -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Terminology of Yacht Parts, Fittings, Sails & Sheets Etc

Terminology of yacht parts, fittings, sails & sheets etc. Some of the obvious, and not so obvious, parts encountered on model yachts (and full size yachts). Bowsie, flat. Small drilled ‘plate’ through which runs a line, or cord, for adjustment of that line. Pre-war bowsies were often made in ivory, some were made in a fine plywood; today hard plastic is used. Bowsie, ring . A circular version of the flat bowsie, usually for larger yachts such as the A-class. Deck eye. An eye on a horizontal plate with fixing holes, located on the deck. Normally used for accepting backstay/forestay attachment, also shroud attachment on smaller yachts. Eyebolt. An eye, at the end of a threaded spigot, or bolt. Eyelet, sail. A sail eyelet is a brass part, in the shape of a ‘funnel’ before compression, and when pressed into a hole in a sail it makes a firm metal ring. It is then used to facilitate making off a line (or on occasions a wire hawser in full size practise). Larger/stronger eyelets used on laying up covers for full size boats, were turnovers , where a brass ring was firstly sewn in place over a hole punched in the sail or sheet, the turnover (eyelet) was then hammered in place using a rawhide mallet and dies. It made an immensely strong eyelet. Ferrule (slang, crimp). A brass ferrule, or sleeve, which when made off on one end of a wire, secures/attaches it by means of a loop made in the wire to a fitting or line. Head crane. -

Sailing Skills & Seamanship

Sailing Skills & Seamanship - Course Description The U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary's Sailing Skills and Seamanship Course (SS&S) is a comprehensive course designed for both experienced and novice sailboat operators. The course, now in its 6 th edition that was published in 2008, is divided into parts: 10 core requirement two-to four-hour lessons plus 6 elective lessons that will enhance the skills required for a safe voyage in all conditions. These courses can be taught in addition to the core courses. TOPICS INCLUDE About Sailboats - Language of the sea; components of a sailboat; standing and running rigging; sails; types of sailboats; boat building materials; guidance on selecting and purchasing a boat. How A Boat Sails - Reading the wind; points of sailing, running, close hauled, reaching, sail shape; sail adjustments; when the wind picks up. Basic Sailboat Maneuvering - Tacking; jibbing; sailing a course; stability and angle of heel; knowing your boat. Rigging And Boat Handling - Stepping the mast; making sail; hoisting the sails; leaving the dock; mooring; controlling the sails; anchoring; weighing anchor. Equipment For Your Boat - Requirements for your boat; your boat's equipment; legal considerations. Trailering Your Sailboat - Legal considerations; practical considerations; selecting your trailer; the towing vehicle; handling your trailer; pre-departure checks; launching; retrieving; raising the mast; storing your boat and trailer; theft prevention; aquatic nuisance species; float plan. Your Highway Signs - Protection of ATONS; buoyage -

Mast Furling Installation Guide

NORTH SAILS MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE Congratulations on purchasing your new North Mast Furling Mainsail. This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots. Step 1 Unpack your Sail Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later. Step 2 Attach the Mainsail Tack Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs. NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide. Step 2 www.northsails.com Step 3 Attach the Mainsail Clew Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. -

470 Rigging Instructions

470 Rigging Instructions 1. Stepping the mast up. a. Ensure the mast partner slit is open. b. With the boat on the grass, step inside (clean or remove shoes first!), and receive the mast. i. Ensure the heel of the mast is clean. ii. If continuous jib sheet, ensure around the mast slot. c. Place the heel of the mast in the shoe inside the boat d. Lean the mast forward, against the deck. e. Free the forestay and attach it. f. Free the shrouds and trapeze, ensure not twisted, and attach them. g. Free the other controls (vang, cunningham, spinnaker halyard, topping lift, down haul), ensure not twisted and attach them. h. Close the mast partner slit. 2. Rigging the boat a. Attach the tack and head of the jib. b. Run the foot of the main sail through the boom, attach the clew and tack. i. On some boats the tack can only be attached after the boom is secured in the gooseneck. ii. On some of the boats it is easier to hoist the mainsail and latch its halyard first, and only then attach the gooseneck and the tack. c. Attach the all 3 ends of the spinnaker and bag it. i. Note: the spinnaker lines should be the outermost, while its halyard stays close to the mast (between the jib lines). ii. Ensure the halyards are not twisted. d. Hoist the jib and attach the halyard cable loop to the tensioner hook. i. VERY IMPORTANT: Make sure the hook catches the metal cable loop and not the messenger line!!! e. -

Boom Vang Rigging

Congratulations! You purchased the best known and best built pocket cruising vessels available. We invite you to spend a few moments with the following pages to become better acquainted with your new West Wight Potter. If at any point we can assist you, please call 800 433 4080 Fair Winds International Marine Standing Rigging The mast is a 2” aluminum extrusion with a slot on the aft side to which the sail’s boltrope or mainsail slides (options item) enter when hoisting the main sail. Attached to the mast will be two side stays, called Shrouds, and a Forestay. These three stainless cables represent the standing rigging of the West Wight Potter 15. The attachment points for the shroud adjusters are on the side of the deck. Looking at the boat you will find ¼” U-Bolts mounted through the deck on either side of the boat and the adjuster goes over these U-Bolts. Once the shroud adjuster slides in, the clevis pin inserts through the adjuster and is held in place with a lock ring. When both side stays are in place we move onto the mast raising. Mast Raising First, remove the mast pin holding the mast base in the bow pulpit. Second, move the mast back towards the mast step on the cabin top of the boat and pin the mast base into the aft section of the mast step (the mast step is bolted onto the cabin top of the boat). The mast crutch on the transom of the boat will support the aft end of the mast. -

Sailing Trans-Atlantic on the USCG Barque Eagle

PassageRite of Sailing Trans-Atlantic On The USCG Barque Eagle odern life is complicated. I needed a car, a bus, a train and a taxi to get to my square-rigger. When no cabs could be had, a young police officer offered me a lift. Musing on my last conveyance in such a vehicle, I thought, My, how a touch of gray can change your circumstances. It was May 6, and I had come to New London, Connecticut, to join the Coast Guard training barque Eagle to sail her to Dublin, Ireland. A snotty, wet Measterly met me at the pier, speaking more of March than May. The spires of New Lon- don and the I-95 bridge jutted from the murk, and a portion of a nuclear submarine was discernible across the Thames River at General Dynamics Electric Boat. It was a day for sitting beside a wood stove, not for going to sea, but here I was, and somehow it seemed altogether fitting for going aboard a sailing ship. The next morning was organized chaos. Cadets lugged sea bags aboard. Human chains passed stores across the gangway and down into the deepest recesses of the ship. Station bills were posted and duties disseminated. I met my shipmates in passing and in passageways. Boatswain Aaron Stapleton instructed me in the use of a climbing harness and then escorted me — and the mayor of New London — up the foremast. By completing this evolution, I was qualified in the future to work aloft. Once stowed for sea, all hands mustered amidships. -

December 2007 Crew Journal of the Barque James Craig

December 2007 Crew journal of the barque James Craig Full & By December 2007 Full & By The crew journal of the barque James Craig http://www.australianheritagefleet.com.au/JCraig/JCraig.html Compiled by Peter Davey [email protected] Production and photos by John Spiers All crew and others associated with the James Craig are very welcome to submit material. The opinions expressed in this journal may not necessarily be the viewpoint of the Sydney Maritime Museum, the Sydney Heritage Fleet or the crew of the James Craig or its officers. 2 December 2007 Full & By APEC parade of sail - Windeward Bound, New Endeavour, James Craig, Endeavour replica, One and All Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 7 Radio procedures on James Craig adio procedures being used onboard discomfort. Effective communication Rare from professional to appalling relies on message being concise and clear. - mostly on the appalling side. The radio Consider carefully what is to be said before intercoms are not mobile phones. beginning to transmit. Other operators may The ship, and the ship’s company are be waiting to use the network. judged by our appearance and our radio procedures. Remember you may have Some standard words and phases. to justify your transmission to a marine Affirm - Yes, or correct, or that is cor- court of inquiry. All radio transmissions rect. or I agree on VHF Port working frequencies are Negative - No, or this is incorrect or monitored and tape recorded by the Port Permission not granted. -

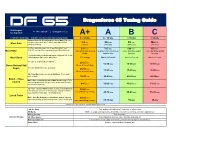

Sail Tuning Guide LINK

DF 65 Dragonforce 65 Tuning Guide Phil Burgess M - 0413 200 608 E - [email protected] 1st July 2020 A+ A B C Estimated wind range - depends on wave action and tacking ability 0 - 10 kts 8 - 15 kts > 15 kts > 20 kts Distance from Jib Pivot Eyelet to front of Mast (Can also use gate control as a ram to induce mast bend without line 4th Line Line Aft Mast Gate 3rd 5th Max changing forestay). (175 mm) (176 mm) (177 mm) (178 mm) A+ From backstay crane hole to top of backstay hook 951 mm. 785 mm. 698 mm. 620 mm. A, B, C From top of Forestay tang to top of backstay hook. Mast Rake From soft to firm as wind Slightly firmer backstay & Firmer backstay & tight Firmer backstay & tight builds tight forestay forestay forestay Tension Backstay so Mast bend matches Mainsail luff, so sail Mast Bend easily flops from side to side when tilted Soft settings Match luff round Match luff round Match luff round At centre of Jib Boom deepest point 20-25 mm, 15-20 mm 15-20 mm 10-15 mm Boom Outhaul Sail 15 mm at top of range At centre of Main Boom deepest point Depth 25-30 mm, 15-25 mm 15-20 mm 10-20 mm 15 mm at top of range Jib - from Mast centre to end of Jib Boom. Place small mark on deck 38-43 mm 40-45mm 40-45mm 40-45mm Boom - Close Main - from centreline at end of Main Boom. (Adjust Tx for hauled exponential adjustment for last 20 mm sheet travel for high and low pointing mode) 8-15 mm 10-20 mm 15-25 mm 15-25 mm Jib - from Centre of Mast to leech at mid point of jib leech. -

How the Beaufort Scale Affects Your Sail Plan

How the Beaufort scale affects your sail plan The Beaufort scale is a measurement that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea. Used in the sea area forecast it allows sailors to anticipate the condition that they are likely to face. Modern cruising yachts have become wider over the years to allow more room inside the boat when berthed. This offers the occupants a large living space but does have an effect on the handling of the boat. A wide beam, relatively short keel and rudder mean that if they have too much sail up they have a greater tendency to broach into the wind. Broaching, although dramatic for those onboard, is nothing more than the boat turning into the wind and is easy to rectify by carrying less sail. If the helm is struggling to keep the boat in a straight line then the boat has too much ‘weather helm’ i.e. the boat keeps turning into the wind- in this instance it is necessary to reduce sail. Racer/cruisers are often narrower than their cruising counter parts, with longer keels and rudders which mean they are less likely to broach, but often more difficult to sail with a small crew. Cruising yachts often have large overlapping jibs or genoas and relevantly small main sails. This allows the sail area to be reduced quickly and easily simply by furling away some head sail. The main sail is used to balance boat as the main drive comes from the head sail. Racer cruisers will often have smaller jibs and larger main sails, so reducing the sail area means reefing the main sail first and using the jib to balance the boat.