Oom Shmoom Revisited: Sharett and Ben-Gurion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ihe White House Iashington

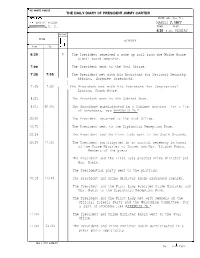

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

Statistical Information

STATISTICAL INFORMATION VOTES CAST FOR SENATORS IN 2008, 2010, and 2012 [Compiled from official statistics obtained by the Clerk of the House. Figures in the last column, for the 2012 election, may include totals for more candidates than the ones shown.] Vote Total vote State 2008 2010 2012 cast in 2012 Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Alabama ....................... 752,391 1,305,383 515,619 968,181 .................... .................... .................... Alaska .......................... 1,51,767 147,814 60,045 90,839 .................... .................... .................... Arizona ........................ .................... .................... 592,011 1,005,615 1,036,542 1,104,457 2,243,422 Arkansas ...................... 804,678 .................... 288,156 451,618 .................... .................... .................... California ..................... .................... .................... 5,218,441 4,217,366 7,864,624 4,713,887 12,578,511 Colorado ...................... 1,230,994 990,755 851,590 822,731 .................... .................... .................... Connecticut .................. .................... .................... 605,204 498,341 792,983 604,569 1,511,764 Delaware ...................... 257,539 140,595 174,012 123,053 265,415 115,700 399,606 Florida .......................... .................... .................... 1,092,936 2,645,743 4,523,451 3,458,267 8,189,946 Georgia ........................ 909,923 1,228,033 996,516 1,489,904 ................... -

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left by Prof. Hillel Frisch BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 875, June 26, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The crisis of the Israeli left is reflected in the sharply declining interest within Israel in Yitzhak Rabin compared to Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir. The opposite trend is visible abroad. The problem of the left is that it is Israelis who vote, not the world community. A search for the term “Yitzhak Rabin” in Hebrew in Google Trends reveals a sharp decline in interest since 2005, the tenth anniversary of Rabin’s assassination. The decline is precipitous in the years immediately following 2005 and then levels off. Still, the decline over time is substantial. If searches for Rabin in 2004 represent 100, the high point, this figure was down to 6 by October 2017 – less than one-twelfth the number of searches 13 years before. Interest in Rabin is also sharply correlated to the period of commemoration that occurs in November of each year on the anniversary of the assassination. Obviously, official remembrance days heighten awareness in any particular year, but they have done little to arrest the overall decline in interest in Rabin. “Yitzhak Rabin” in Google Trends The same exercise regarding Menachem Begin and Shamir shows a stark contrast. Whereas interest in Rabin has declined sharply, interest in Begin and Shamir remains surprisingly constant – not only over the years, but within the calendar year. These comparisons say nothing about the absolute number of searches over time among the three leaders. They do say something conclusive, however, about trends in interest and therefore in the collective historical memory. -

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

Mirette F. Mabrouk Mirette F

Mirette F. Mabrouk Mirette F. Mabrouk is director of communications for the Economic Research Forum (ERF), and a nonresident fellow at the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. She was formerly associate director for publishing operations at the American University in Cairo (AUC) Press and the publisher of The Daily News Egypt, the country’s only independent English- language daily newspaper. Mabrouk has over 20 years of experience in journalism. She founded The Daily News Egypt (formerly The Daily Star Egypt) in May of 2005 and it rapidly became the leading English newspaper in the country. Mabrouk wrote regularly, with her opinion columns generally being the paper’s top-emailed article during the week of their publication. In 1995, she was asked to found Business Today, becoming the country’s youngest editor of a national magazine. It went on to become the top independent business magazine in the region. She was formerly an editor for Arab Media and Society, an online journal on the media’s role in Arab and Muslim societies published by AUC’s Kamal Adham Center for Journalism Training and Research, and the Middle East Centre at St. Anthony’s College, Oxford. She has served on the boards of the Egyptian Chapter of Young Arab Leaders, a regional non-profit organization dedicated to development, and the non-governmental organization Masr Habibti. She has been involved with the Aspen Institute (Washington DC), the Consumer Unity Trust Society (Jaipur, India.), and the Brains Trust at the Evian Group, a trade-advocacy think tank based in Lausanne, Switzerland. -

Why Hawks Become Doves

ONE INTRODUCTION An Individual Level Explanation of Foreign Policy Change Why do some hawkish leaders become dovish, thereby pursuing dramatic change in their states’ foreign policies, while other hawks remain committed to the status quo? Recent history provides us with important examples of prominent foreign policy “hawks” who underwent dovish transformations. These leaders’ shifts led, in turn, to major changes in their states’ foreign policies. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s peace overtures to Jerusalem, just four years after launching a surprise attack on Israel, led to the Egypt‑Israel Peace Treaty in 1979. In South Africa, Nelson Mandela’s repudiation of violence in his 1989 letter to President P. W. Botha set the stage for the country’s transition from apartheid to democracy. In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev moved his country from a policy of containment to détente between 1985 and 1991. Yet major foreign policy transformations have occurred not only in authoritarian regimes, where change, some would argue, may more like‑ ly occur as a result of the whims of an authoritarian leader, but also in democratic societies.1 For example, Charles de Gaulle, the French military leader who became president of the Fifth Republic, reversed the longstand‑ ing French policy vis‑à‑vis the Algerians by granting them independence. The United States also has undergone a number of major foreign policy reversals. President Richard Nixon’s famous 1972 visit to China marked a significant turnaround of American‑Chinese relations. President Ronald Reagan began seeking a rapprochement with the Soviet Union even before 1 © 2014 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 WHY HAWKS BECOME DOVES Gorbachev came to power and, in so doing, effectively reversed his hardline stance toward the country to which he had formerly referred as “the evil empire” (Farnham 2001; Fischer 1997). -

Shimon Peres the Leadership Series

Center for Israel Education Shimon Peres The Leadership Series 1. Childhood and Early Years “In Israel, a land lacking in natural resources, we learned to appreciate our greatest natonal advantage: our minds. Through creatvity and innovaton, we transformed barren deserts into fourishing felds and pioneered new fronters in science and technology.” -Shimon Peres Shimon Peres was born on August 2, 1923, in Wiszniew, Poland (now Vishnyeva, Belarus). His parents were Yitzhak and Sara Perski. Shimon’s family spoke Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian at home. Shimon also learned Polish at school. His father was a wealthy Cover Photo Credit: Mark Neyman, Natonal Photo Collecton tmber merchant, and his mother was a librarian. Peres had a younger brother named Gershon. Leadership Series: Shimon Peres Copyright © 2019 by Center for Israel Educaton His grandfather, Rabbi Zvi Meltzer, impacted his All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or life greatly. Peres discussed his memories with his transmited in any form or by any means without writen permission from the author. grandfather: Published by Center for Israel Educaton, P.O. Box 15129, Atlanta, GA 30333. “As a child, I grew up in my grandfather's home. www.israeled.org … I was educated by him.… My grandfather [email protected] taught me Talmud.” In 1932, when Peres was 9 years old, his father immigrated to Tel Aviv, in the Land of Israel. In 1934, Shimon and his family followed their father. 1 www.israeled.org. ©Center for Israel Education, 2020 All Rights Reserved Peres at age 13 Kibbutz Geva (1944) Source: Wikimedia Commons. -

Marshall, the Recognition of Israel, and Anti-Semitism by Gerald M. Pops

1 MARSHALL, THE RECOGNITION OF ISRAEL, AND ANTI-SEMITISM By Gerald M. Pops1 George Catlett Marshall is revered throughout the world as the principal military leader of allied forces in World War II and as one of only two generals who were awarded the Nobel Peace prize.1 As Secretary of State, he was known as the father of the post-war Marshall Plan that played a crucial role in the reconstruction of Europe. Notwithstanding, he has been viewed ambivalently by Jewish Americans. This is because he opposed, as Secretary of State, the immediate unilateral recognition by the United States of the new state of Israel. The meaning ascribed to this act by Clark Clifford “with” Richard Holbrooke, in their 1991 book, Counsel to the President: A Memoir, together with a retrospective editorial in the Washington Post by Holbrooke seventeen years later, did much to shape the thinking of many American Jews respecting Marshall’s motivation for opposing the immediate recognition of the new Jewish state. They attributed Marshall’s opposition, in part, to anti-Semitic staff members within the Department of State. In the words of Holbrooke: Beneath the surface lay unspoken but real anti-Semitism on the 2 part of some (but not all) policymakers. 1 The author thanks the following people: Paul Barron and Mark Stoler, for help with the search for materials and ideas; Jeffrey Kozak, for assistance using Marshall Library sources; Brian Shaw and other members of the Marshall Foundation for encouragement to complete the project, and Marcia Pops and Hillary Bhaskaran for editing and stylistic advice. -

The Politics of Normalization: Israel Studies in the Academy Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F

The Politics of Normalization: Israel Studies in the Academy Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Miriam Shenkar, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Educational Policy and Leadership The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Robert F. Lawson, Advisor Matt Goldish Douglas Macbeth Copyright by Miriam Shenkar 2010 Abstract This study will examine the emergence of Israel studies at the university level. Historical precedents for departments of Hebrew language instruction, Jewish studies centers and area studies will be examined to determine where Israel studies chair holders are emerging. After defining Israel studies, a qualitative methodological approach will be used to evaluate the disciplinary focus of this emerging area. Curriculum available from and degree granting capabilities of various programs will be examined. In addition surveys taken of Israel studies scholars will provide their assessments of the development of the subject. Four case studies will highlight Israel studies as it is emerging in two public (land grant institutions) versus two private universities. An emphasis will be placed on why Israel studies might be located outside Middle Eastern studies. Questions regarding the placing of Israel studies within Jewish studies or Near Eastern Languages and Culture departments will be addressed. The placing of Israel studies chairs and centers involves questions of national and global identity. How these identities are conceptualized by scholars in the field, as well as how they are reflected in the space found for Israel studies scholars are the motivating factors for the case studies. -

Crossroads: the Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Haim Malka Foreword by Samuel W

Malka Crossroads: The Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership Haim Malka Foreword by Samuel W. Lewis The U.S.-Israel partnership is under unprecedented strain. The relationship is deep and coopera- tion remains robust, but the challenges to it now are more profound than ever. Growing differ- ences could undermine the national security of both the United States and Israel, making strong cooperation uncertain in an increasingly volatile and unpredictable Middle East. This volume explores the partnership between the United States and Israel and analyzes how political and strategic dynamics are reshaping the relationship. Drawing on original research and dozens of interviews with U.S. and Israeli officials and former officials, the study traces the development CROSSROADS of the U.S.-Israel relationship, analyzes the sources of current tension, and suggests ways for- ward for policymakers in both countries. The author weaves together historical accounts with current analysis and debates to provide insight into this important yet changing relationship. It is a sobering and keen analysis for anyone concerned with the future of the U.S.-Israel partner- ship and the broader Middle East. Haim Malka is deputy director and senior fellow of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Crossroads The Future of the U.S.-Israel Strategic Partnership HAIM MALKA ISBN 978-0-89206-660-5 FOREWORD BY SAMUEL W. LEWIS Center for Strategic and International Studies Washington, D.C. Ë|xHSKITCy066605zv*:+:!:+:! CSIS 2011 C ROSSROADS ABOUT CSIS At a time of new global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to decisionmakers in government, in- ternational institutions, the private sector, and civil society.