Pressman on Carter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ihe White House Iashington

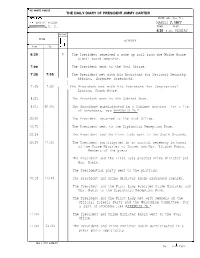

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Carter Diplomacy in the Negotiations Between Egypt and Israel, October 1978- March 1979

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter now, including display on the World Wide Web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Jay Schaefer April 10, 2018 Push and Pull: Carter Diplomacy in the Negotiations Between Egypt and Israel, October 1978- March 1979 by Jay Schaefer Kenneth W. Stein Adviser History Kenneth W. Stein Adviser Joseph P. Crespino Committee Member Dan Reiter Committee Member 2018 Push and Pull: Carter Diplomacy in the Negotiations Between Egypt and Israel, October 1978- March 1979 By Jay Schaefer Kenneth W. Stein Adviser An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors History 2018 Abstract Push and Pull: Carter Diplomacy in the Negotiations Between Egypt and Israel, October 1978- March 1979 By Jay Schaefer This thesis is a critical examination of President Jimmy Carter’s Middle East negotiating strategy between the signing of the Camp David Accords and the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty. -

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog Author Other Authors Title Call Letter Call number Volume Closed shelf Notes Donated By In Memory Of (unkown) (unknown) history of the presidents for children E 176.1 .Un4 Closed shelf 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Ruth Goree and Jane Brown 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Anonymous 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Bobbie Meadows Beulah Hodges 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1981 Presidential Inaugural Committee (U.S.) A Great New Beginning: the 1981 Inaugural Story E 877.2 .G73 A Citizen of Western New York Bancroft, George Memoirs of General Andrew Jackson, Seventh President of the United States E 382 .M53 Closed shelf John Ben Shepperd A.P.F., Inc. A Catalogue of Frames, Fifteenth Century to Present N 8550 .A2 (1973) A.P.F. Inc. Aaron, Ira E. Carter, Sylvia Take a Bow PZ 8.9 .A135 Abbott, David W. Political Parties: Leadership, Organization, Linkage JK 2265 .A6 Abbott, John S.C. Conwell, Russell H. Lives of the Presidents of the United States of America E 176.1 .A249 Closed shelf Ector County Library Abbott, John S.C. -

Camp David's Shadow

Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Seth Anziska All rights reserved ABSTRACT Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska This dissertation examines the emergence of the 1978 Camp David Accords and the consequences for Israel, the Palestinians, and the wider Middle East. Utilizing archival sources and oral history interviews from across Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Camp David’s Shadow recasts the early history of the peace process. It explains how a comprehensive settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict with provisions for a resolution of the Palestinian question gave way to the facilitation of bilateral peace between Egypt and Israel. As recently declassified sources reveal, the completion of the Camp David Accords—via intensive American efforts— actually enabled Israeli expansion across the Green Line, undermining the possibility of Palestinian sovereignty in the occupied territories. By examining how both the concept and diplomatic practice of autonomy were utilized to address the Palestinian question, and the implications of the subsequent Israeli and U.S. military intervention in Lebanon, the dissertation explains how and why the Camp David process and its aftermath adversely shaped the prospects of a negotiated settlement between Israelis and Palestinians in the 1990s. In linking the developments of the late 1970s and 1980s with the Madrid Conference and Oslo Accords in the decade that followed, the dissertation charts the role played by American, Middle Eastern, international, and domestic actors in curtailing the possibility of Palestinian self-determination. -

Statistical Information

STATISTICAL INFORMATION VOTES CAST FOR SENATORS IN 2008, 2010, and 2012 [Compiled from official statistics obtained by the Clerk of the House. Figures in the last column, for the 2012 election, may include totals for more candidates than the ones shown.] Vote Total vote State 2008 2010 2012 cast in 2012 Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Democrat Republican Alabama ....................... 752,391 1,305,383 515,619 968,181 .................... .................... .................... Alaska .......................... 1,51,767 147,814 60,045 90,839 .................... .................... .................... Arizona ........................ .................... .................... 592,011 1,005,615 1,036,542 1,104,457 2,243,422 Arkansas ...................... 804,678 .................... 288,156 451,618 .................... .................... .................... California ..................... .................... .................... 5,218,441 4,217,366 7,864,624 4,713,887 12,578,511 Colorado ...................... 1,230,994 990,755 851,590 822,731 .................... .................... .................... Connecticut .................. .................... .................... 605,204 498,341 792,983 604,569 1,511,764 Delaware ...................... 257,539 140,595 174,012 123,053 265,415 115,700 399,606 Florida .......................... .................... .................... 1,092,936 2,645,743 4,523,451 3,458,267 8,189,946 Georgia ........................ 909,923 1,228,033 996,516 1,489,904 ................... -

It Seemed Like I Was Unusually Qualified for This

LIZ: Please wait just one moment. I’m LIZ: And it is an honor for us to be recording this on two devices and want working with you! It’s also interesting to turn both of them on… how different this play is from Cleo. What was the spark for Camp David? LAWRENCE: You’re doing the best practices of journalism, Liz, with the LAWRENCE: I got a call when I was in redundancy. a cab in New York City from Gerald Rafshoon, who was Jimmy Carter’s LIZ: Well, thank you, Larry. It is great to media advisor when he was in the hear that from you as I was just about White House and also when he was to say that I interview playwrights Governor of Georgia, and he asked frequently, but it’s a bit intimidating “Would you be interested in writing a interviewing you knowing that you are play about Camp David?” The truth is, a Pulitzer Prize-winning interviewer of I had never talked to Jerry Rafshoon other people, so I’m glad I’m doing well before and he caught me totally by so far. surprise. It was great working with you on Cleo But I began to consider the fact that I two seasons ago, and we look forward had lived in Georgia when Carter was to having you back here at the Alley for governor. I had lived in Egypt when Camp David! This will be your second Anwar Sadat became president after production with us and I love that you Gamal Abdel Nasser’s death, and I had can just drive over from Austin. -

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left

Interest in Past Leaders Reflects the Crisis on the Israeli Left by Prof. Hillel Frisch BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 875, June 26, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The crisis of the Israeli left is reflected in the sharply declining interest within Israel in Yitzhak Rabin compared to Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir. The opposite trend is visible abroad. The problem of the left is that it is Israelis who vote, not the world community. A search for the term “Yitzhak Rabin” in Hebrew in Google Trends reveals a sharp decline in interest since 2005, the tenth anniversary of Rabin’s assassination. The decline is precipitous in the years immediately following 2005 and then levels off. Still, the decline over time is substantial. If searches for Rabin in 2004 represent 100, the high point, this figure was down to 6 by October 2017 – less than one-twelfth the number of searches 13 years before. Interest in Rabin is also sharply correlated to the period of commemoration that occurs in November of each year on the anniversary of the assassination. Obviously, official remembrance days heighten awareness in any particular year, but they have done little to arrest the overall decline in interest in Rabin. “Yitzhak Rabin” in Google Trends The same exercise regarding Menachem Begin and Shamir shows a stark contrast. Whereas interest in Rabin has declined sharply, interest in Begin and Shamir remains surprisingly constant – not only over the years, but within the calendar year. These comparisons say nothing about the absolute number of searches over time among the three leaders. They do say something conclusive, however, about trends in interest and therefore in the collective historical memory. -

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money.