Marshall, the Recognition of Israel, and Anti-Semitism by Gerald M. Pops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

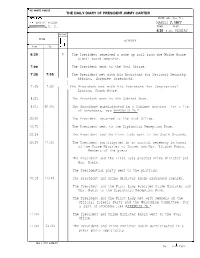

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

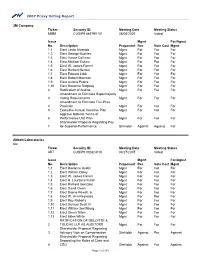

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

S. HRG. 106±225 HEARINGS ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. RICH- ARD C. HOLBROOKE TO SERVE AS U.S. AMBAS- SADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 17, 22, AND 24, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57±735 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1999 Page Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 4 Boxer, Barbara, U.S. Senator from California, prepared statement of ............... 34 Helms, Jesse, U.S. Senator from North Carolina, opening statement ................ 1 Holbrooke, Hon. Richard C., nominee to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations .................................................................................................................. 10 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 16 Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, U.S. Senator from New York, statement ................. 9 Warner, John W., U.S. Senator from Virginia, statement ................................... 7 TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1999 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 47 Helms, Jesse, U.S. -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

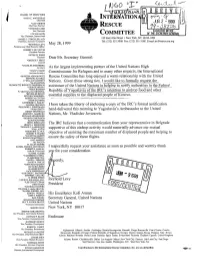

Intermationa Rescue

fiJUULfnl BOARD OF DIRECTORS 'T* . <!/ ~"ll I I 'JOHN C. WHITEHEAD INTERMATIONA 1 Chairman *LEO CHERNE JUN 2-1999 Chairman Emeritus RESCUE 'WINSTON LORD Vice Chairman EXECUTIVE OFFICE LPV ULLMANN COMMITTEE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Vice Chairman, International 122 East 42nd Street • New York, NY 10168-1289 •JAMES C. STRICKLER, M.D. Chairman, Executive Committee Tel: (212)551-3000 Fax:(212)551-3180 E-mail:[email protected] •REYNOLD LEVY May 28, 1999 President and Chief Executive Officer ROBERT P. DE VECCHI President Emeritus *PETER W. WEISS Treasurer Dear Mr. Secretary General: •GEORGE F. HRITZ Counsel •CHARLES STERNBERG Secretary As the largest implementing partner of the United Nations High •NANCY STARR Assistant Secretary Commissioner for Refugees and in many other respects, the International •MORTON ABRAMOWITZ Rescue Committee has long enjoyed a warm relationship with the United ERNESTO ALVAREZ F. WILLIAM BARNETT Nations. Given these strong ties, I would like to formally request the •ALAN BATKIN GEORGETTE BENNETT-TANENBAUM •GEORGE BIDDLE assistance of the Unitejd Nations in helping to notify authorities in the Federal •VERA BLINKEN W. MICHAEL BLUMENTHAL Republic of Yugoslavia of the IRC' s intention to airdrop food and other •BEVERLEE BRUCE NESTOR CARBONELL essential supplies to the displaced people of Kosovo. ROBERT M. GOTTEN JODIE EASTMAN KATHERINE G. FARLEY SANDRA FELDMAN I have taken the liberty of enclosing a copy of the IRC's formal notification THEODORE J. FORSTMANN •TOM GERETY hand-delivered this morning to Yugoslavia's Ambassador to the United HENRY GRUNWALD MORTON I. HAMBURG Nations, Mr. Vladislav Jovanovic. RICHARD HOLBROOKE •MARVIN JOSEPHSON ALTON KASTNER IRENA KIRXLAND The IRC believes that a communication from your representative in Belgrade HENRY A. -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included. -

The Crisis of Crimea and Ukraine Key Lessons for President Obama from Presidents Reagan and Clinton

The Crisis of Crimea and Ukraine Key Lessons for President Obama from Presidents Reagan and Clinton By Rudy deLeon and Aarthi Gunasekaran May 14, 2014 In the past two months, the Crimea and Ukraine crisis has grown. Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula, the Ukrainian government and pro-Russian militia are engaged in a back and forth standoff in eastern Ukraine, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has threatened that the conflict “essentially puts the nation on the brink of civil war.” 1 The United States has been at the forefront of building international support for Ukraine, and the Obama administration continues to assemble Western support. However, efforts to reach a diplomatic settlement, or at least to reduce immediate ten- sions, are still in progress.2 As the Obama administration prepares its next steps in response to Russia in Ukraine, it can examine lessons from two other administrations in times of crisis. First, the Reagan administration’s reaction in 1983 to the Soviet downing of a civilian Korean airliner and its response to the terrorist attack against U.S. Marines on a peacekeeping mission in Lebanon. Second, the Clinton administration’s initiative to proactively expand and deepen partnerships in Europe during the 1990s through its Partnership for Peace. President Ronald Reagan faced an exceptional provocation with the downing of the Korean airliner and a month later, with the terrorist attack against U.S. Marines in Lebanon, resulting in significant American and allied casualties. Keeping costly and possibly destabilizing military options as his last resort, President Reagan used vigor- ous but measured words to condemn these lawless actions and rallied the interna- tional community in opposition. -

Clinton Presidential Records in Response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests Listed in Attachment A

VIA EMAIL (LM 2017-126) September 5, 2017 The Honorable Donald F. McGahn, II Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. McGahn: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 29,090 pages, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 11,437 pages restricted. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 17,653 pages. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is December 1, 2017, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

Pressnotes the DIPLOMAT Tribeca2015

PRESS NOTES thediplomatfilm.com PRESS CONTACTS Adam J. Segal/Jacqueline Gurgui of The 2050 Group facebook.com/thediplomatmovie (202) 422-4673 • [email protected] (845) 706-1332 • [email protected] twitter.com/thediplomatfilm Lana Iny/Jessica Driscoll of HBO (212) 512-1462 • [email protected] (212) 512-1322 • [email protected] SCREENINGS AT TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Public Screenings World Premiere Screening & Tribeca Talks program Thursday, April 23 at 6:30 PM at SVA Theater 1 (School of Visual Arts) After the movie: Stay for a conversation with director David Holbrooke, producer Stacey Reiss, New York Times columnist Roger Cohen, Ronan Farrow, Special Advisor to Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, 2009-2011. Panel Discussion moderated by Katie Couric, Global News Anchor, Yahoo! News. Saturday, April 25 at 6:00 PM at Bow Tie Cinemas Chelsea (Theater 7) Followed by filmmaker Q&A Sunday, April 26 at 3:00 PM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 6) Followed by filmmaker Q&A Press & Industry Screenings Friday, April 24 at 9:15 AM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 5) Saturday, April 25 at 9:15 AM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 5) HBO DEBUT: FALL 2015 HBO will air THE DIPLOMAT this fall in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Peace Accords, which ended the war in Bosnia and was one of Richard Holbrooke’s greatest foreign policy achievements. The Diplomat is not only a telling and forceful reminder of the singular political achievements of a complicated man, once dubbed the diplomatic hope of a generation, but also a unique and moving story of a son’s love for – and personal coming-to-terms with – an all-too-imperfect father whose work and exceptional career achievements more often than not took precedence over his family.