Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

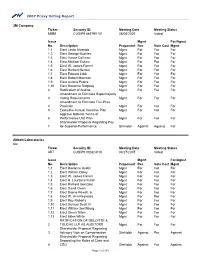

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

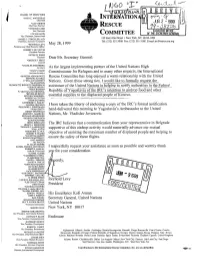

Intermationa Rescue

fiJUULfnl BOARD OF DIRECTORS 'T* . <!/ ~"ll I I 'JOHN C. WHITEHEAD INTERMATIONA 1 Chairman *LEO CHERNE JUN 2-1999 Chairman Emeritus RESCUE 'WINSTON LORD Vice Chairman EXECUTIVE OFFICE LPV ULLMANN COMMITTEE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Vice Chairman, International 122 East 42nd Street • New York, NY 10168-1289 •JAMES C. STRICKLER, M.D. Chairman, Executive Committee Tel: (212)551-3000 Fax:(212)551-3180 E-mail:[email protected] •REYNOLD LEVY May 28, 1999 President and Chief Executive Officer ROBERT P. DE VECCHI President Emeritus *PETER W. WEISS Treasurer Dear Mr. Secretary General: •GEORGE F. HRITZ Counsel •CHARLES STERNBERG Secretary As the largest implementing partner of the United Nations High •NANCY STARR Assistant Secretary Commissioner for Refugees and in many other respects, the International •MORTON ABRAMOWITZ Rescue Committee has long enjoyed a warm relationship with the United ERNESTO ALVAREZ F. WILLIAM BARNETT Nations. Given these strong ties, I would like to formally request the •ALAN BATKIN GEORGETTE BENNETT-TANENBAUM •GEORGE BIDDLE assistance of the Unitejd Nations in helping to notify authorities in the Federal •VERA BLINKEN W. MICHAEL BLUMENTHAL Republic of Yugoslavia of the IRC' s intention to airdrop food and other •BEVERLEE BRUCE NESTOR CARBONELL essential supplies to the displaced people of Kosovo. ROBERT M. GOTTEN JODIE EASTMAN KATHERINE G. FARLEY SANDRA FELDMAN I have taken the liberty of enclosing a copy of the IRC's formal notification THEODORE J. FORSTMANN •TOM GERETY hand-delivered this morning to Yugoslavia's Ambassador to the United HENRY GRUNWALD MORTON I. HAMBURG Nations, Mr. Vladislav Jovanovic. RICHARD HOLBROOKE •MARVIN JOSEPHSON ALTON KASTNER IRENA KIRXLAND The IRC believes that a communication from your representative in Belgrade HENRY A. -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included. -

The Crisis of Crimea and Ukraine Key Lessons for President Obama from Presidents Reagan and Clinton

The Crisis of Crimea and Ukraine Key Lessons for President Obama from Presidents Reagan and Clinton By Rudy deLeon and Aarthi Gunasekaran May 14, 2014 In the past two months, the Crimea and Ukraine crisis has grown. Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula, the Ukrainian government and pro-Russian militia are engaged in a back and forth standoff in eastern Ukraine, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has threatened that the conflict “essentially puts the nation on the brink of civil war.” 1 The United States has been at the forefront of building international support for Ukraine, and the Obama administration continues to assemble Western support. However, efforts to reach a diplomatic settlement, or at least to reduce immediate ten- sions, are still in progress.2 As the Obama administration prepares its next steps in response to Russia in Ukraine, it can examine lessons from two other administrations in times of crisis. First, the Reagan administration’s reaction in 1983 to the Soviet downing of a civilian Korean airliner and its response to the terrorist attack against U.S. Marines on a peacekeeping mission in Lebanon. Second, the Clinton administration’s initiative to proactively expand and deepen partnerships in Europe during the 1990s through its Partnership for Peace. President Ronald Reagan faced an exceptional provocation with the downing of the Korean airliner and a month later, with the terrorist attack against U.S. Marines in Lebanon, resulting in significant American and allied casualties. Keeping costly and possibly destabilizing military options as his last resort, President Reagan used vigor- ous but measured words to condemn these lawless actions and rallied the interna- tional community in opposition. -

Clinton Presidential Records in Response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests Listed in Attachment A

VIA EMAIL (LM 2017-126) September 5, 2017 The Honorable Donald F. McGahn, II Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. McGahn: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 29,090 pages, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 11,437 pages restricted. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 17,653 pages. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is December 1, 2017, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

Pressnotes the DIPLOMAT Tribeca2015

PRESS NOTES thediplomatfilm.com PRESS CONTACTS Adam J. Segal/Jacqueline Gurgui of The 2050 Group facebook.com/thediplomatmovie (202) 422-4673 • [email protected] (845) 706-1332 • [email protected] twitter.com/thediplomatfilm Lana Iny/Jessica Driscoll of HBO (212) 512-1462 • [email protected] (212) 512-1322 • [email protected] SCREENINGS AT TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Public Screenings World Premiere Screening & Tribeca Talks program Thursday, April 23 at 6:30 PM at SVA Theater 1 (School of Visual Arts) After the movie: Stay for a conversation with director David Holbrooke, producer Stacey Reiss, New York Times columnist Roger Cohen, Ronan Farrow, Special Advisor to Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, 2009-2011. Panel Discussion moderated by Katie Couric, Global News Anchor, Yahoo! News. Saturday, April 25 at 6:00 PM at Bow Tie Cinemas Chelsea (Theater 7) Followed by filmmaker Q&A Sunday, April 26 at 3:00 PM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 6) Followed by filmmaker Q&A Press & Industry Screenings Friday, April 24 at 9:15 AM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 5) Saturday, April 25 at 9:15 AM at Regal Battery Park Stadium 11 (Theater 5) HBO DEBUT: FALL 2015 HBO will air THE DIPLOMAT this fall in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Peace Accords, which ended the war in Bosnia and was one of Richard Holbrooke’s greatest foreign policy achievements. The Diplomat is not only a telling and forceful reminder of the singular political achievements of a complicated man, once dubbed the diplomatic hope of a generation, but also a unique and moving story of a son’s love for – and personal coming-to-terms with – an all-too-imperfect father whose work and exceptional career achievements more often than not took precedence over his family. -

United Nations Issues: Cabinet Rank of the US

Updated December 22, 2020 United Nations Issues: Cabinet Rank of the U.S. Permanent Representative The U.S. Permanent Representative is the chief as a means of maintaining communication and the flow of representative of the United States to the United Nations. information among key Administration officials. The President appoints the Permanent Representative with the advice and consent of the Senate. Of the 30 individuals By tradition, permanent Cabinet membership comprises the President, the heads of the executive departments and, in who have served since 1946, approximately two-thirds have more recent decades, the Vice President. Beginning with been accorded Cabinet rank by Presidents. Some Members of Congress have demonstrated an ongoing interest in the Dwight D. Eisenhower, each President also has accorded Cabinet rank to select senior executive branch leaders, Cabinet rank of the Permanent Representative in the context including the U.S. Permanent Representative. The positions of the Senate confirmation process and broader U.S. policy toward the United Nations. On November 24, 2020, and individuals granted this distinction vary by presidency and, sometimes, within a presidency. Some positions, President-elect Biden announced his intent to nominate including the Administrator of the Environmental Linda Thomas-Greenfield to be Permanent Representative, with Cabinet rank. Biden stated that he will accord Cabinet Protection Agency, the United States Trade Representative, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and status to Greenfield “because I want to hear her voice on all the White House Chief of Staff, have all consistently been the major foreign policy discussions we have.” accorded this status over the past three decades. -

Nomination of Leon Panetta to Be Director, Central Intelligence Agency

S. HRG. 111–172 NOMINATION OF LEON PANETTA TO BE DIRECTOR, CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY HEARINGS BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 5, 2009 FEBRUARY 6, 2009 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Intelligence ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 52–741 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 14:45 Dec 01, 2009 Jkt 052741 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\52741.TXT SHAUN PsN: DPROCT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE [Established by S. Res. 400, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.] DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri, Vice Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah RON WYDEN, Oregon OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine EVAN BAYH, Indiana SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland RICHARD BURR, North Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin TOM COBURN, Oklahoma BILL NELSON, Florida JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island HARRY REID, Nevada, Ex Officio MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio CARL LEVIN, Michigan, Ex Officio JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio DAVID GRANNIS, Staff Director LOUIS B. TUCKER, Minority Staff Director KATHLEEN P. MCGHEE, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 14:45 Dec 01, 2009 Jkt 052741 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\52741.TXT SHAUN PsN: DPROCT CONTENTS FEBRUARY 5, 2009 OPENING STATEMENTS Feinstein, Hon. -

Summary of Conclusions for Meeting of the NSC Principals Committee DATE: December 5, 1995 LOCATION: White House Situation Room TIME: 2:30 P.M

C05962599 SITUATION ROOM (WE) 12. 13. '95 18:20 NO. 1460051904 PAGE 3. NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL 21391 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20504 Approved for Release CIA Historical ollections Division AR 70-14 1OCT201 Summary of Conclusions for Meeting of the NSC Principals Committee DATE: December 5, 1995 LOCATION: White House Situation Room TIME: 2:30 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. SUBJECT: Summary of Conclusions of Principals Committee Meeting on Bosnia -(-S-)- PARTICIPANTS: .CHAIR OMB Anthony Lake Gordon Adams Phil DuSault OVP - Rick Saunders CIA John Deutch STATE George Tenet Strobe Talbott Peter Tarnoff, JCS Richard Holbrooke Gen. John Shalikashvili LTG Wesley Clark DEFENSE John Walsh Walter Slocombe James Pardew White House Sandy Berger USUN Nancy Soderberg Amb. Madeleine Albright (via secure video) NSC David Scheffer Alexander Vershbow John Feeley Summary of Conclusions Congressional Strategy 1. Principals reviewed the draft. text of the Dole-McCain resolution for support of U.S. armed forces participating in IFOR. They agreed that while we should try to eliminate language in the preamble that characterizes the Dayton agreement as "ratification" of ethnic cleansing, our priority should be to improve the operative paragraphs. They agreed we should seek to scale back efforts to commit the United States to "lead" rather. Classified by: Andrew D. Sens Reason: 1/5 (a,b,d) Declassify on: 12/05/05 5 9 6 2 5 9 9 C0 SE SITUATION ROOM (WE) 12.13. 95 18:21 NO. 1460051904 PAGE 4 " ____ 2 than "coordinate" international efforts to equip and train Bosnian forces. -(Et 2. Principals agreed that the Administration could accept requirements to report to the Congress within 30 days on U.S. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1998 - June 30,1999 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-•1789 TTele . (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail communications@cfr. org Officers and Directors, 1999–2000 Officers Directors Term Expiring 2004 Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 2000 John Deutch Chairman of the Board Jessica P.Einhorn Carla A. Hills Maurice R. Greenberg Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Robert D. Hormats* Vice Chairman Maurice R. Greenberg William J. McDonough* Leslie H. Gelb Theodore C. Sorensen President George J. Mitchell George Soros* Michael P.Peters Warren B. Rudman Senior Vice President, Chief Operating Term Expiring 2001 Leslie H. Gelb Officer, and National Director ex officio Lee Cullum Paula J. Dobriansky Vice President, Washington Program Mario L. Baeza Honorary Officers David Kellogg Thomas R. Donahue and Directors Emeriti Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Richard C. Holbrooke Douglas Dillon and Publisher Peter G. Peterson† Caryl P.Haskins Lawrence J. Korb Robert B. Zoellick Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Vice President, Studies David Rockefeller Term Expiring 2002 Elise Carlson Lewis Honorary Chairman Vice President, Membership Paul A. Allaire and Fellowship Affairs Robert A. Scalapino Roone Arledge Abraham F. Lowenthal Cyrus R.Vance John E. Bryson Vice President Glenn E. Watts Kenneth W. Dam Anne R. Luzzatto Vice President, Meetings Frank Savage Janice L. Murray Laura D’Andrea Tyson Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2003 Judith Gustafson Secretary Peggy Dulany Martin S.