Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detente and World Order

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 6 Number 1 Spring Article 4 May 2020 Detente and World Order Josef Korbel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Josef Korbel, Detente and World Order, 6 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 9 (1976). This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. MYRES S. McDOUGAL DISTINGUISHED LECTURE D tente and World Order JOSEF KORBEL* This is the first annual Myres S. McDougal Distinguished Lec- ture in International Law and Policy, presented at the University of Denver College of Law, April 20, 1976. Sponsored by the Stu- dent Bar Association, the International Legal Studies Program, the Denver International Law Society and the DENVER JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND POLICY, the lecture series will present eminent jurists and scholars addressing topical issues of interna- tional law and policy. I. I feel greatly honored by being asked to open this series of lectures in honor of the doyen of international legal studies, Professor McDougal. I really cannot add anything to the acco- lades except to say that I join with all others in my profound admiration and respect for Professor McDougal. I am also in- clined to extend my admiration to all professors and students of international law, whose intellectual stamina and courage as they plow so laboriously the arid lands of international behav- ior I greatly admire. -

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

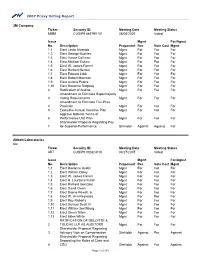

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, December 21, 1998 Volume 34ÐNumber 51 Pages 2471±2507 1 VerDate 21-DEC-98 09:37 Dec 23, 1998 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P51DE4.000 TXED02 PsN: TXED02 Contents Addresses to the Nation Joint Statements Iraq, announcing military strikesÐ2494 Joint United States-European Union Statement on Chapter IV New Transatlantic Addresses and Remarks Agenda DialoguesÐ2505 United States-European Union Declaration on See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders the Middle East Peace ProcessÐ2504 Gaza United States-European Union Joint Luncheon hosted by Chairman Arafat in Statement on Cooperation in the Western Gaza CityÐ2486 BalkansÐ2502 Palestinian National Council and other United States-European Union Statement on Palestinian organizations in Gaza CityÐ Cooperation in the Global EconomyÐ2503 2487 Meetings With Foreign Leaders Iraq, military strikesÐ2497 European Union leadersÐ2502, 2503, 2504, Israel 2505 Arrival ceremony in Tel AvivÐ2472 Israel Dinner hosted by Prime Minister President WeizmanÐ2472, 2478 Netanyahu in JerusalemÐ2483 Prime Minister NetanyahuÐ2472, 2473, Menorah lighting in JerusalemÐ2478 2479, 2483 People of Israel in JerusalemÐ2479 Palestinian Authority, Chairman ArafatÐ2485, Radio addressÐ2471 2486, 2487 Special Olympics dinnerÐ2500, 2501 Proclamations Trilateral discussions at Erez CrossingÐ2492 Wright Brothers DayÐ2499 Executive Orders Statements by the President Crime ratesÐ2479 Half-Day Closing of Executive Departments Deaths and Agencies of the Federal Government A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.Ð2494 on Thursday, December 24, 1998Ð2500 Lawton ChilesÐ2472 Morris UdallÐ2479 Interviews With the News Media Puerto Rico, status referendumÐ2492 Exchanges with reporters Supplementary Materials Erez Crossing, IsraelÐ2492 Acts approved by the PresidentÐ2507 Gaza City, GazaÐ2485 Checklist of White House press releasesÐ Oval OfficeÐ2497 2506 News Conference With Prime Minister Digest of other White House Netanyahu in Jerusalem, Israel, December announcementsÐ2505 13 (No. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

Conversation Number 39-1 Portion of a Telephone Conversation Between

Conversation Number 39-1 Portion of a telephone conversation between the President and Henry A. Kissinger. This portion was recorded on May 24, 1973 at an unknown time between 1:27 and 1:29 p.m. [This conversation is cross-referenced with conversation 440-35.] The National Archives and Records Administration prepared the following log of this conversation. Watergate -White House response -White Paper -National security Conversation Number 39-4 Portion of a telephone conversation between the President and Hugh Scott. This portion was recorded on May 24, 1973 between 1:36 and 1:38 p.m. [This conversation is cross-referenced with conversation 440-38.] The National Archives and Records Administration prepared the following log of this conversation. Watergate -Scott's actions, May 23 -Ronald L. Ziegler Scott's schedule Watergate -White House response -National security -Effect on United States foreign policy -Scott's possible statement -Scott's statement, May 23 Conversation Number 39-5 Portion of a telephone conversation between the President and Leslie C. Arends. This portion was recorded on May 24, 1973 between 1:39 and 1:40 p.m. [This conversation is cross- referenced with conversation 440-39.] The National Archives and Records Administration prepared the following log of this conversation. Watergate -Republican congressmen's morale -White House response -White Paper -National security -Effect on United States foreign policy Conversation Number 39-16 Portions of a telephone conversation between the President and Alexander M. Haig, Jr. These portions were recorded on May 25, 1973 at an unknown time between 12:58 and 1:25 a.m. -

The President's Commission on the Celebration of Women in American

The President’s Commission on Susan B. Elizabeth the Celebration of Anthony Cady Women in Stanton American History March 1, 1999 Sojourner Lucretia Ida B. Truth Mott Wells “Because we must tell and retell, learn and relearn, these women’s stories, and we must make it our personal mission, in our everyday lives, to pass these stories on to our daughters and sons. Because we cannot—we must not—ever forget that the rights and opportunities we enjoy as women today were not just bestowed upon us by some benevolent ruler. They were fought for, agonized over, marched for, jailed for and even died for by brave and persistent women and men who came before us.... That is one of the great joys and beauties of the American experiment. We are always striving to build and move toward a more perfect union, that we on every occasion keep faith with our founding ideas and translate them into reality.” Hillary Rodham Clinton On the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the First Women’s Rights Convention Seneca Falls, NY July 16, 1998 Celebrating Women’s History Recommendations to President William Jefferson Clinton from the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. Ellen Ochoa, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Irene Wurtzel March 1, 1999 Table of Contents Executive Order 13090 ................................................................................1 -

Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

S. HRG. 106±225 HEARINGS ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. RICH- ARD C. HOLBROOKE TO SERVE AS U.S. AMBAS- SADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 17, 22, AND 24, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57±735 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1999 Page Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 4 Boxer, Barbara, U.S. Senator from California, prepared statement of ............... 34 Helms, Jesse, U.S. Senator from North Carolina, opening statement ................ 1 Holbrooke, Hon. Richard C., nominee to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations .................................................................................................................. 10 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 16 Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, U.S. Senator from New York, statement ................. 9 Warner, John W., U.S. Senator from Virginia, statement ................................... 7 TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1999 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 47 Helms, Jesse, U.S. -

The Political and Symbolic Importance of the United States in the Creation of Czechoslovakia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Drawing borders: the political and symbolic importance of the United States in the creation of Czechoslovakia Samantha Borgeson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Borgeson, Samantha, "Drawing borders: the political and symbolic importance of the United States in the creation of Czechoslovakia" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 342. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/342 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAWING BORDERS: THE POLITICAL AND SYMBOLIC IMPORTANCE OF THE UNITED STATES IN THE CREATION OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA Samantha Borgeson Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts And Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Madeleine Albright

Madeleine K. Albright is chair of Albright Stonebridge Group, a global strategy firm, and chair of Albright Capital Management LLC, an investment advisory firm focused on emerging markets. Albright was the 64th Secretary of State of the United States. In 1997, she was named the first female Secretary of State and became, at that time, the highest ranking woman in the history of the U.S. government. As Secretary of State, Albright reinforced America’s alliances, advocated democracy and human rights and promoted American trade and business, labor and environmental standards abroad. From 1993 to 1997, Albright served as the U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations and as a member of the President’s Cabinet. She is a professor in the Practice of Diplomacy at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. She chairs both the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, the Pew Global Attitudes Project and serves as president of the Truman Scholarship Foundation. Albright serves on the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Policy Board, a group tasked with providing the secretary of defense with independent, informed advice and opinion concerning matters of defense policy. She also serves on the Board of Directors of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Board of Trustees for the Aspen Institute. In 2009, Albright was asked by NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen to chair a group of experts focused on developing NATO’s New Strategic Concept. On May 29, 2012 President Obama awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom to Dr. Albright – the nation's highest civilian honor - citing the inspiration her life is to all and that her scholarship and insight continue to make the world a better, more peaceful place. -

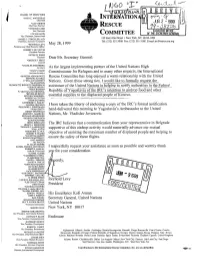

Intermationa Rescue

fiJUULfnl BOARD OF DIRECTORS 'T* . <!/ ~"ll I I 'JOHN C. WHITEHEAD INTERMATIONA 1 Chairman *LEO CHERNE JUN 2-1999 Chairman Emeritus RESCUE 'WINSTON LORD Vice Chairman EXECUTIVE OFFICE LPV ULLMANN COMMITTEE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Vice Chairman, International 122 East 42nd Street • New York, NY 10168-1289 •JAMES C. STRICKLER, M.D. Chairman, Executive Committee Tel: (212)551-3000 Fax:(212)551-3180 E-mail:[email protected] •REYNOLD LEVY May 28, 1999 President and Chief Executive Officer ROBERT P. DE VECCHI President Emeritus *PETER W. WEISS Treasurer Dear Mr. Secretary General: •GEORGE F. HRITZ Counsel •CHARLES STERNBERG Secretary As the largest implementing partner of the United Nations High •NANCY STARR Assistant Secretary Commissioner for Refugees and in many other respects, the International •MORTON ABRAMOWITZ Rescue Committee has long enjoyed a warm relationship with the United ERNESTO ALVAREZ F. WILLIAM BARNETT Nations. Given these strong ties, I would like to formally request the •ALAN BATKIN GEORGETTE BENNETT-TANENBAUM •GEORGE BIDDLE assistance of the Unitejd Nations in helping to notify authorities in the Federal •VERA BLINKEN W. MICHAEL BLUMENTHAL Republic of Yugoslavia of the IRC' s intention to airdrop food and other •BEVERLEE BRUCE NESTOR CARBONELL essential supplies to the displaced people of Kosovo. ROBERT M. GOTTEN JODIE EASTMAN KATHERINE G. FARLEY SANDRA FELDMAN I have taken the liberty of enclosing a copy of the IRC's formal notification THEODORE J. FORSTMANN •TOM GERETY hand-delivered this morning to Yugoslavia's Ambassador to the United HENRY GRUNWALD MORTON I. HAMBURG Nations, Mr. Vladislav Jovanovic. RICHARD HOLBROOKE •MARVIN JOSEPHSON ALTON KASTNER IRENA KIRXLAND The IRC believes that a communication from your representative in Belgrade HENRY A.