Interview with Chas W. Freeman Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

Mihaela Tirca

UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA ANGLESA I ALEMANYA Programa de Doctorat en Llengües, Literatures i Cultures i les seues Aplicacions LITERARY ACTIVISM IN ANGLOWAITI WRITING: GENDER IN NADA FARIS’S LITERATURE Presentada por MIHAELA TIRCA Dirigida por Dra. Carme Manuel Cuenca Dr. Vicent Cucarella Ramon València, Octubre 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to begin by expressing my most heartfelt gratitude and special appreciation to Professor Carme Manuel for accepting me to carry out this work under her directions. This thesis would have not been possible without her invaluable guidance toward the analysis of Nada Faris’s literary works and continuous monitoring. I cannot thank her enough for her permanent help into this study. In addition, her motivating words constituted the motor of this thesis. I am profoundly grateful to her for providing me with the means to accomplish this work. I consider myself to be enormously privileged to have been her student throughout all these years. I am deeply indebted to Professor María José Coperías whose constant assistance and instrumental support helped me to carry out this project. I feel extremely honored to have had the opportunity to be under her supervision. I humbly extend my appreciation and thanks to Professor Vicent Cucarella Ramon for kindly agreeing to supervise this thesis. I am also thankful to Nada Faris’s significant suggestions and clarifying notes about her work and for inspiring me every day for a couple of months by sharing the light of a candle. My most profound gratitude goes to my mother and my grandmother who always encouraged me to continue this thesis even when circumstances in my life were the least favorable. -

American A6&,Nts.- 190°4

-4A N 4-k V: W .P- J wo -4. --Z 7.", JV 1,!., "At V.1", .VT h,c iL IV 4k k'V P, Ae s"V kt lh Vd N, s_ XL` -I .pr- -t "I 7 r "I :' Ar Part III. -- The Chuckchee - Social Organization by W. Bogoras 1909 1- -, ,--- .. F I .1- 1 I--14-1 1 904. Leiden, -New York', !, E. J. BRI 1, I,Ltl.d. G;., E. STECHERT-8 Co. Printe.rs ai-d l' ub'ishers, American A6&,nts.- I 9D -.Ii 190°4- XVIII. ORGANIZATION OF FAMILY AND FAMILY-GROUP. MAN IN THE FAMILY. The units of social organization amona the Chukchee are quite unstable, excepting the family, which forms the basis of the social relations between members of the tribe. Even family ties are not absolutely binding, and single persons often break them and leave their family relations. Grown-up sons frequently leave their parents and go away to distant localities in search of a fortune. The youths of the Reindeer tribe descend to the coast, and those of the Maritime Chukchee go inland to live with the reindeer-breeders. Not a few of the Chukchee tales open with a description of the life of a lone man who does not know any other people, and who lives in a wild place. It may be said that a lone man living by himself forms the real unit of Chukchee society. Even woman, whose social position is much inferior to that of man, sometimes breaks away from father or husband and goes to live with other people, though the family may pursue her, and, if she is caught, bring her back by force. -

Study of Caste

H STUDY OF CASTE BY P. LAKSHMI NARASU Author of "The Essence of Buddhism' MADRAS K. V. RAGHAVULU, PUBLISHER, 367, Mint Street. Printed by V. RAMASWAMY SASTRULU & SONS at the " VAVILLA " PRESS, MADRAS—1932. f All Rights Reservtd by th* Author. To SIR PITTI THY AG A ROY A as an expression of friendship and gratitude. FOREWORD. This book is based on arfcioles origiDally contributed to a weekly of Madras devoted to social reform. At the time of their appearance a wish was expressed that they might be given a more permanent form by elaboration into a book. In fulfilment of this wish I have revised those articles and enlarged them with much additional matter. The book makes no pretentions either to erudition or to originality. Though I have not given references, I have laid under contribution much of the literature bearing on the subject of caste. The book is addressed not to savants, but solely to such mea of common sense as have been drawn to consider the ques tion of caste. He who fights social intolerance, slavery and injustice need offer neither substitute nor constructive theory. Caste is a crippli^jg disease. The physicians duty is to guard against diseasb or destroy it. Yet no one considers the work of the physician as negative. The attainment of liberty and justice has always been a negative process. With out rebelling against social institutions and destroying custom there can never be the tree exercise of liberty and justice. A physician can, however, be of no use where there is no vita lity. -

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

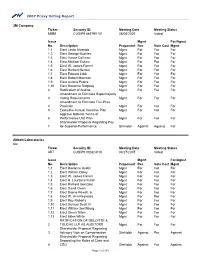

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

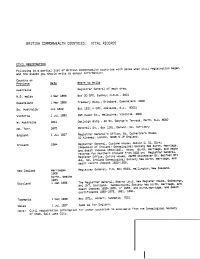

British Isles

BRITISH COMMONWEALTH COUNTRIES: VITAL RECORDS CIVIL REGISTRATICN Following is a partial list of British Ccmmcnwealth countries with dates when civil registration began, and the places you should writ~ to obtain information: Ccuntry or Prevince Q!!! Where to Write .Au$t'ralia Registrar Ganer-a! of each area. N.S. wales 1 Mar 1856 Sex 30 GPO, Sydney, N.S.W., 2001 Queensland 1 Mar 1856 Treasury Bldg., Brisbane, Queensland 4000 So. Australia Jul 1842 8ex 1531 H Gr\), Adelaide, S.A. 5CCCl Victoria 1 Jul 1853 295 Cuesn St., Melbourne, Victoria XCO W. .Australia 1841 Cak!eigh 61dg., 22 St. Gear-ge's Terrace, Perth, W.A. eoco Nc. Terr. 1870 Mitchell St., Box 1281. OarNin, Nc. Territory England 1 Jul 1837 Registrar General's Office, St. catherine's House, 10 Kinsway. Loncen, 'AC2S 6 JP England. Ireland 1864 Registrar General, Custcme House. Dublin C. 10, Eire, (Recuolic(Republic of Ireland) Genealogical Society has bir~h, marriage, and death indexes 1864-1921. Nete: Birth, rtarl"'iage,rmt'l"'iage, atld death records farfor Nor~hern Ireland frcm 1922 an: Registrar General, Regis~erOffice, Oxford House. 49~5 Chichester St. Selfast STI 4HL, No~ !re1.a.rld Genealcgical Scciety has birth, narriage, and death recordreccrd indexes 1922-l959~ New Z!!aland marriages Registrar General, P.O~ Sox =023, wellingtcn, New Zealand. 1008 birth, deaths 1924 Scotland 1 Jan 1855 The Registrar General, Search Unit, New Register House, Edinburgh, EHl 3YT, SCCtland~ Genealogical Saei~tyScei~ty has bir~h,birth, marriage, and death indexes 1855-1955, or 1956, and birt%'\ crarriage, and death cer~ificates 1855-1875, 1881. -

Rock Is Life

Rock Is Life http://www.rock-is-life.com/reviewsinbrief.htm Reviews In Brief (2007) (2006) (2005) (2004) 2007 STARZ Greatest Hits Live MVD Entertainment Group 2007 "The live collection of the 70’s rockers greatest hits seems to capture the band in fine form. The CD is compiled from at least 3 different performances and while I found the sound to be adequate to mediocre, the quality of their material does seem to shine through. While I wouldn’t put the band in my own personal Top 10 of 1970’s rockers, they are pretty good. I think it is a shame I wasn’t musically aware in the 70’s because I probably would have liked the band. They’ve got a lively and energetic sound tied to that particular era and it does keep the ears engaged, even during the first half of the disc where the quality of the recording isn’t even as good as some bootlegs I’ve listened to over the years. The audio quality is the biggest problem I had with the entire disc. I think if you are going to reissue this type of album, you really need to make the sound more Official Site presentable than what a typical bootlegger could accomplish. You want to check out tracks like “Detroit Girls”, “Any Way That You Want It”, and “Cherry Baby” in particular, but surprisingly at least to me, each song is pretty good. Search Amazon: If you like the 70’s rock era, you probably know of the band. You’ll definitely like this release. -

Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: the Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: The Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism Logan Cox and David A. Anderson Introduction Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) shares a history common to most of Africa: years of colonization by a European power, followed by a war for independence and subsequent autocratic rule by a leader in that fight for independence. Zimbabwe is, however, unique in that it was once the most diverse and promising economy on the continent. In spite of its historical potential, today Zimbabwe ranks third worst in the world in “Indicators of Instability” leading the world in Human Flight, Uneven Development, and Economy, while ranking high in each of the remaining eight categories tracked (see figure below)1. Zimbabwe is experiencing a “brain drain” with the emigration of doctors, engineers, and agricultural experts, the professionals that are crucial to revitalizing the Zimbabwean economy2. If this was not enough, 2008 inflation was running at an annual rate of 231 million percent, with 80% of the population lives below the poverty line.3 Figure 1: Source: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0 1 Foreign Policy, “The Failed States Index 2008”, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0, (accessed August 29, 2008). 2 The Fund for Peace, “Zimbabwe 2007.” The Fund for Peace. http://www.fundforpeace.org/web/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=280&Itemid=432 (accessed September 30, 2008). 3 BBC News, “Zimbabwean bank issues new notes,” British Broadcasting Company. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7642046.stm (accessed October 3, 2008). -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Acts of the Commissioners of the United Colonies of New England

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ..CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 083 937 122 Cornell University Library ^^ The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924083937122 RECORDS OF PLYMOUTH COLONY. %tk of i\t Comittissioitfi's of !lje Initfb Colonies of felo €\4ml YOL. I. ] 643-1051. RECORDS OF THE COLONY OF NEW PLYMOUTH IN NEW ENGLAND. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS. EDITED BY DAVID PULSIFER, CLERK IN THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH, MEMBER OF THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC-GENEALOfilCAL SOCIETY, VIXLOW OP TllK AMERICAN STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION, CORKESPONDINQ MEMBER OP THE ESSEX INSTITUTE, AND OF THE RHODE ISLAND, NEW YORK, COXNKCTICUT AND WISCONSIN BISTORICAL SOCIETIES. %t\^ of Jlje ^tinimissioners of Ijje InM Colonirs of Btfo ^iiglank VOL. I. 1643-1651. BOSTON: FROM THE PRESS OF WILLIAM WHITE, rRINTEK TO THE COMMONWEALTH. 185 9. ^CCRMELL^ ;UNIVERSITY LJ BRARY C0MM0.\))EALT11 OF MASSACHUSETTS. ^etrflarn's f eprtnunt. Boston, Apkil o, 1858. By virtue of Chapter forty-one of the Eesolves of the year one thousand eight hundred fifty-eight, I appoint David Pulsifee, Esq., of Boston, to super- intend the printing of the New Plymouth Records, and to proceed with the copying, as provided in previous resolves, in such manner and form as he may consider most appropriate for the undertaking. Mr. Pulsifer has devoted many years to the careful exploration and transcription of ancient records, in the archives of the County Courts and of the Commonwealth.