Can Big Government Be Rolled Back? by Michael Barone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

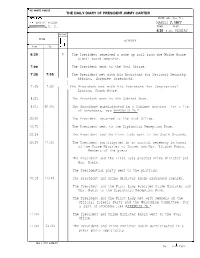

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

In Defence of the Court's Integrity

In Defence of the Court’s Integrity 17 In Defence of the Court’s Integrity: The Role of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in the Defeat of the Court-Packing Plan of 1937 Ryan Coates Honours, Durham University ‘No greater mistake can be made than to think that our institutions are fixed or may not be changed for the worse. We are a young nation and nothing can be taken for granted. If our institutions are maintained in their integrity, and if change shall mean improvement, it will be because the intelligent and the worthy constantly generate the motive power which, distributed over a thousand lines of communication, develops that appreciation of the standards of decency and justice which we have delighted to call the common sense of the American people.’ Hughes in 1909 ‘Our institutions were not designed to bring about uniformity of opinion; if they had been, we might well abandon hope.’ Hughes in 1925 ‘While what I am about to say would ordinarily be held in confidence, I feel that I am justified in revealing it in defence of the Court’s integrity.’ Hughes in the 1940s In early 1927, ten years before his intervention against the court-packing plan, Charles Evans Hughes, former Governor of New York, former Republican presidential candidate, former Secretary of State, and most significantly, former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, delivered a series 18 history in the making vol. 3 no. 2 of lectures at his alma mater, Columbia University, on the subject of the Supreme Court.1 These lectures were published the following year as The Supreme Court: Its Foundation, Methods and Achievements (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928). -

The Origins and Application of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Origins and Application of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 We the people of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. — Preamble to the Constitution of the United States of America This preamble sets forth goals for the United States. But when? After adoption of the Constitution, nearly 100 years passed before emancipation, and that involved a civil war. It was more than two generations after that before women were allowed to vote. Our history is replete with discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, and gender. Historically, many societies have survived with homogeneity of race, ethnicity, or religion, but never with homogeneity of gender. Because of this one might expect gender based discrimination to be among the first to fall in a democratic society, rather than one of the last. And yet, the 200 year history of our high court boasts of only two female justices. Only a small percentage of the Congress are female and there has never been a female president or vice- president. England has had its Margaret Thatcher, Israel its Golda Meir, and India its Indra Ghandi. The American Democracy has certainly missed the opportunity to lead the world in gender equality in leadership, and without that how can we expect to see gender equality in society? There will never be complete equality until women themselves help to make the laws and elect lawmakers. -

University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

This dissertation has been 65-12,998 microfilmed exactly as received MATHENY, David Leon, 1931- A COMPAEISON OF SELECTED FOREIGN POLICY SPEECHES OF SENATOR TOM CONNALLY. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1965 ^eech-Theater University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A COMPARISON OP SELECTED FOREIGN POLICY SPEECHES OF SENATOR TOM CONNALLY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY DAVID LEON MATHENY Norman, Oklahoma 1965 A COMPARISON OP SELECTED FOREXON POLICY SPEECHES OP SENATOR TOM CONNALLY APPROVED BY L-'iJi'Ui (^ A -o ç.J^\AjLôLe- DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express thanks to Professor Wayne E. Brockriede and members of the University of Oklahoma Speech Faculty for guidance during the preparation of this dissertation. A special word of thanks should go to Profes sor George T. Tade and the Administration of Texas Christian University for encouragement during the latter stages of the study and to the three M's — Mary, Melissa and Melanie — for great understanding throughout the entire project. TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................... Ill Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ......................... 1 Purpose of the S t u d y ..................... 6 Previous Research......................... 8 Sources of Material....................... 9 Method of Organization ................... 10 II. CONNALLY, THE SPEAKER....................... 12 Connally's Non-Congresslonal Speaking Career.......... 12 General Attributes of Connally's Speaking............................... 17 Conclusion . ........................... 31 III. THE NEUTRALITY ACT DEBATE, 1939............. 32 Connally's Audience for the Neutrality Act Debate.............. 32 The Quest for Neutrality ............ 44 The Senate, Connally and Neutrality. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Sean Brennan

1 Sean Brennan Department of History [email protected] University of Scranton 570-941-4549 (office) Saint Thomas Hall 308C 570-540-5161 (cell) Scranton, PA 18510 EDUCATION Ph.D., History, May 2009 University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN Historical Fields: Twentieth Century Russia, emphasis on Religious, Diplomatic, and Political History Nineteenth Century Russia Twentieth Century Germany History of American Foreign Relations Dissertation: “The Politics of Religion in Soviet-occupied Germany: The Case of Berlin-Brandenburg 1945-1949” Advisor: Dr. Semion Lyandres M.A., History, 2003 Villanova University, Villanova, PA Historical Field: Modern European History 1750-1991 Master’s Thesis: “Building Situations of Strength: Dean Acheson, the Korean War, and German Rearmament June 1950-May 1952” B.A., History, 2001, magna cum laude, with honors Rockhurst University, Kansas City, MO TEACHING POSITIONS Professor of History, University of Scranton, 2009- Adjunct Instructor, University of Notre Dame, 2008-2009 Teaching Assistant, University of Notre Dame 2004-2006 Teaching Assistant, Villanova University, 2002-2003 2 PUBLICATIONS (Books) Warren Austin, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr, and the Cold War at the United Nations 1947-1960 (Forthcoming 2023) The KGB vs the Vatican: Revelations from the Vasili Mitrokhin Archives The Catholic University of America Press (Forthcoming 2021) The Priest Who Put Europe Back Together: The Life of Rev. Fabian Flynn, CP The Catholic University of America Press (December 2018) The Politics of Religion in Soviet-Occupied -

Theda Skocpol

NAMING THE PROBLEM What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight against Global Warming Theda Skocpol Harvard University January 2013 Prepared for the Symposium on THE POLITICS OF AMERICA’S FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING Co-sponsored by the Columbia School of Journalism and the Scholars Strategy Network February 14, 2013, 4-6 pm Tsai Auditorium, Harvard University CONTENTS Making Sense of the Cap and Trade Failure Beyond Easy Answers Did the Economic Downturn Do It? Did Obama Fail to Lead? An Anatomy of Two Reform Campaigns A Regulated Market Approach to Health Reform Harnessing Market Forces to Mitigate Global Warming New Investments in Coalition-Building and Political Capabilities HCAN on the Left Edge of the Possible Climate Reformers Invest in Insider Bargains and Media Ads Outflanked by Extremists The Roots of GOP Opposition Climate Change Denial The Pivotal Battle for Public Opinion in 2006 and 2007 The Tea Party Seals the Deal ii What Can Be Learned? Environmentalists Diagnose the Causes of Death Where Should Philanthropic Money Go? The Politics Next Time Yearning for an Easy Way New Kinds of Insider Deals? Are Market Forces Enough? What Kind of Politics? Using Policy Goals to Build a Broader Coalition The Challenge Named iii “I can’t work on a problem if I cannot name it.” The complaint was registered gently, almost as a musing after-thought at the end of a June 2012 interview I conducted by telephone with one of the nation’s prominent environmental leaders. My interlocutor had played a major role in efforts to get Congress to pass “cap and trade” legislation during 2009 and 2010. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

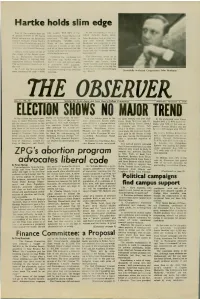

ELECTION SHOWS NO MAJOR TREND Duffy of Connecticut

Hartke holds slim edge Two of the contests that are vote margin. With 80% of the In the 3rd district of Inc.ia ta of special interest to the Notre vote reported, Vance Hartke had which includes South Bend, Dame campus are the Senatorial received 772,000 votes to John Brademas won an easy vic election between Vance Hartke Roudebushes 768,000 votes. tory over Donald Newman. and Richard Roudebush and the None of the networks had Brademas was projected to win Congressional race between John projected a winner at this lime by approximately 20,000 votes. Brademas and Donald Newman. and all of them believed that the This area is traditionally demo cratic and the Brademas victory Indiana is the scene of one of winner could not be declared un was expected. the closest of the Senate races. til the early morning. In it, Democratic incumbent Evidently the candidates lelt The Democrats swept all of Vance Hartke is battling Rep the same way Hirtke went to St. Joseph County. Among the resentative Richard Roudebush. bed at 1 a.m. and will not make casualties was former Notre The vote promises to go down to a statement until morning. Dame security chief Elmer Sokol the wire. Roudebush announced that he who was defeated in his bid for At 2 a.m. the two candidates re-election to the office of Coun will have nothing to say until the Sucessfully re-elected Congressman John Brademas were separated by only a 4000 morning. ty Sheriff. Vol. V., No. 40 THE Serving the Notre Dame and Saint Mary's College CommunityOBSERWednesday, November 4, 1970 ELECTION SHOWS NO MAJOR TREND Duffy of Connecticut. -

REPOWERING AMERICA: Transmission Investment for Economic Stimulus and Climate Change

REPOWERING AMERICA: Transmission investment for economic stimulus and climate change May 2021 Prepared for: London Economics International LLC 717 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 1A Boston, MA 02111 www.londoneconomics.com Disclaimer The analysis London Economics International LLC (“LEI”) provides in this study is intended to illustrate the potential economic benefit of transmission investment in terms of GDP and employment for the American economy (to support economic recovery), and as a potential public policy tool (to support longer term environmental goals to reduce carbon emissions, which will itself create positive economic benefits). While LEI has taken all reasonable care to ensure that its analysis is complete, the interplay of electric infrastructure investment and dynamics of local economies are highly complex, and thus this illustrative analysis does not quantify all tradeoffs and substitution effects, nor attempt to quantify various positive effects from reduced carbon emissions and containment of damages from Climate Change. Furthermore, certain recent developments in the US economy and transmission investment plans of various regions of the US may or may not be included in LEI’s illustrative analysis. This report is not intended to be an evaluation of any specific transmission investment or a definitive assessment of future economic conditions in the US. The opinions expressed in this report as well as any errors or omissions, are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions of other clients of London Economics International LLC. ii London Economics International LLC 717 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 1A Boston, MA 02111 www.londoneconomics.com Table of contents ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................... VI 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

Holt Atherton Special Collections Ms4: Brubeck Collection

HOLT ATHERTON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MS4: BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 1: PAPERS SUBSERIES E: CLIPPINGS BOX 3a : REVIEWS, 1940s-1961 1.E.3.1: REVIEWS, 1940s a- “Jazz Does Campus Comeback but in new Guise it’s a ‘Combo,’” Oakland Tribune, 3-24-47 b- Jack Egan. “Egan finds jury…,” Down Beat, 9-10-47 c- “Local boys draw comment,” <n.s.> [Chicago], 12-1-48 d- Edward Arnow. “Brubeck recital is well-received,” Stockton Record, 1-18-49 e- Don Roessner. “Jazz meets J.S. Bach in the Bay Region,” SF Chronicle, 2- 13-49 f- Robert McCary. “Jazz ensemble in first SF appearance,” SF Chronicle, 3-6- 49 g- Clifford Gessler. “Snap, skill mark UC jazz concert,” <n.s.> [Berkeley CA], n.d. [4-49] h- “Record Reviews---DB Trio on Coronet,” Metronome, 9-49, pg. 31 i- Keith Jones. “Exciting and competent, says this critic,” Daily Californian, 12- 6-49 j- Kenneth Wastell. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-8-49 k- Dick Stewart. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-9-49 l- Ken Wales. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-14-49 m- “Record Reviews: The Month’s best [DB Trio on Coronet],” Metronome, Dec. 1949 n- “Brubeck Sounds Good” - 1949 o- Ralph J. Gleason, “Local Units Give Frisco Plenty to Shout About,” Down Beat, [1949?] 1.E.3.2: REVIEWS, 1950 a- “Record Reviews: Dave Brubeck Trio,” Down Beat, 1-27-50 b- Bill Greer, "A Farewell to Measure from Bach to Bop," The Crossroads, January 1950, Pg. 13 c- Keith Jones. “Dave Brubeck,” Bay Bop, [San Francisco] 2-15-50 d- “Poetic License in Jazz: Brubeck drops in on symphony forum, demonstrates style with Bach-flavored bop,” The Daily Californian, 2-27-50 e- Barry Ulanov.