The Politics of Normalization: Israel Studies in the Academy Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

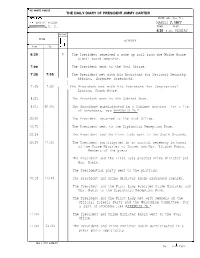

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

Rutgers Jewish Film Festival Goes Virtual, November 8–22

The Allen and Joan Bildner Center BildnerCenter.rutgers.edu for the Study of Jewish Life [email protected] Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 12 College Avenue 848-932-2033 New Brunswick, NJ 08901-1282 Fax: 732-932-3052 October 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EDITOR’S NOTE: For press inquiries, please contact Darcy Maher at [email protected] or call 732-406-6584. For more information, please visit the website BildnerCenter.Rutgers.edu/film. RUTGERS JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL GOES VIRTUAL, NOVEMBER 8–22 NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – Tickets are now on sale for the 21st annual Rutgers Jewish Film Festival, which will be presented entirely online from November 8 through 22. This year’s festival features a curated slate of award-winning dramatic and documentary films from Israel, the United States, and Germany that explore and illuminate Jewish history, culture, and identity. The virtual festival offers a user-friendly platform that will make it easy to view inspiring and entertaining films from the comfort and safety of one’s home. Many films will also include a Q&A component with filmmakers, scholars, and special guests on the Zoom platform. The festival is sponsored by Rutgers’ Allen and Joan Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life and is made possible by a generous grant from the Karma Foundation. The festival kicks-off on Sunday, November 8, with the opening film Aulcie, the inspiring story of basketball legend Aulcie Perry. A Newark native turned Israeli citizen, Perry put Israel on the map as a member of the Maccabi Tel Aviv team in the 1970s. -

Briefing: Labor Zionism and the Histadrut

Briefing: Labor Zionism and the Histadrut International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network-Labor, & Labor for Palestine (US), April 13, 2010 We are thus asking the international trade unions to Jewish working class in any country of the boycott the Histadrut to pressure it to guarantee Diaspora.‖6 rights for our workers and to pressure the The socialist movement in Russia, where most government to end the occupation and to recognize Jews lived, was implacably opposed to Zionism, the full rights of the Palestinian people. ―Palestinian which pandered to the very Tsarist officials who Unions call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions,‖ sponsored anti-Semitic pogroms. Similarly, in the February 11, 2007.1 United States, ―[p]overty pushed [Jewish] workers We must call for the isolation of Histadrut, Israel’s into unions organized by the revolutionary minority,‖ racist trade union, which supports unconditionally and ―[a]t its prime, the Jewish labor movement the occupation of Palestine and the inhumane loathed Zionism,‖7 which conspicuously abstained treatment of the Arab workers in Israel. COSATU, from fighting for immigrant workers‘ rights. June 24-26, 2009.2 • Anti-Bolshevism. It was partly to reverse this • Overview. In their call for Boycott, Divestment Jewish working class hostility to Zionism that, on 2 and Sanctions (BDS) against Apartheid Israel, all November 1917, Britain issued the Balfour Palestinian trade union bodies have specifically Declaration, which promised a ―Jewish National targeted the Histadrut, the Zionist labor federation. Home‖ in Palestine. As discussed below, this is because the Histadrut The British government was particularly anxious has used its image as a ―progressive‖ institution to to weaken Jewish support for the Bolsheviks, who spearhead—and whitewash—racism, apartheid, vowed to take Russia, a key British ally, out of the dispossession and ethnic cleansing against the war. -

Israel Resource Cards (Digital Use)

WESTERN WALL ַה ּכֹו ֶתל ַה ַּמ ַעָר ִבי The Western Wall, known as the Kotel, is revered as the holiest site for the Jewish people. A part of the outer retaining wall of the Second Temple that was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, it is the place closest to the ancient Holy of Holies, where only the Kohanim— —Jewish priests were allowed access. When Israel gained independence in 1948, Jordan controlled the Western Wall and all of the Old City of Jerusalem; the city was reunified in the 1967 Six-Day War. The Western Wall is considered an Orthodox synagogue by Israeli authorities, with separate prayer spaces for men and women. A mixed egalitarian prayer area operates along a nearby section of the Temple’s retaining wall, raising to the forefront contemporary ideas of religious expression—a prime example of how Israel navigates between past and present. SITES AND INSIGHTS theicenter.org SHUK ׁשוּק Every Israeli city has an open-air market, or shuk, where vendors sell everything from fresh fruits and vegetables to clothing, appliances, and souvenirs. There’s no other place that feels more authentically Israeli than a shuk on Friday afternoon, as seemingly everyone shops for Shabbat. Drawn by the freshness and variety of produce, Israelis and tourists alike flock to the shuk, turning it into a microcosm of the country. Shuks in smaller cities and towns operate just one day per week, while larger markets often play a key role in the city’s cultural life. At night, after the vendors go home, Machaneh Yehuda— —Jerusalem’s shuk, turns into the city’s nightlife hub. -

SHATZMILLER, Joseph MG 31, D 9 Finding Aid No

-ii- SHATZMILLER, Joseph MG 31, D 9 Finding Aid No. 1677 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................... iii Description of Papers ............................................ iii Research Potential . .. iv A. CORRESPONDENCE WITH FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES ............ 1 B. JEWISH STUDIES PROGRAMME, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO ......... 7 C. PERSONAL AND ACADEMIC CAREER RECORDS .................. 8 Index . 10 -iii- INTRODUCTION Born in Haifa, Israel, Joseph Shatzmiller was educated at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem where he specialized in Jewish and European history. He received his M.A. in l965 and was a teaching assistant there from l962-l965. From l960 to l965 he served on the editorial board of the Weizmann Institute Archives. As one of the project researchers, he was involved in the publication of several volumes of Chaim Weizmann's letters. In l967 he received his doctorate from Aix-en-Provence University in France. His thesis was prepared under the direction of Professor Georges Duby and was titled, "Recherches sur la communate juive de Manosque au Moyen Age." It was published as a book in l973. Shatzmiller was Professor of History at the University of Haifa from l967 to l972 and was Chairman of its Department of Jewish History from l970-l972. Professor Shatzmiller came to Canada in August l972 to join the staff of the Department of History at the University of Toronto. He served as Visiting Associate Professor from l972 to l974 and became a Full Professor in l974. He taught at the Harvard University Summer School in l973 and was a Visiting Professor at the Université de Nice (France), l982-l983. A teacher of Jewish and French history, Professor Shatzmiller specializes in medieval Jewish studies and has published over fifty articles on Jewish life in medieval France, Germany, Italy and Spain. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

Jewish-Transjordanian Relations 1921-1948

JEWISH-TRANSJORDANIAN RELATIONS 1921-48 This page intentionally left blank JEWISH-TRANSJORDANIAN RELATIONS 1921-48 YOAV GELBER University ofHaifa ~ ~~o~;~;n~~~up LONDON AND NEW YORK Firs/ publishd in /1)1)7 bv FRANK CASS & CO. LTD. This edition published 20 13 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 1997 Yoav Gelber British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Gelber, Yoav Jewish-Transjordanian relations, 1921-48 1. Zionism 2. Jews- Politics and government 3. Israel Foreign relations-Jordan 4. Jordan- Foreign relations Israel I. Tide 327.5'694'05695 ISBN 0-7146-4675-X (cloth) ISBN 0-7146-4206-1 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gelber, Yoav. Jewish-Transjordanian relations, 1921-48 I Yo'av Gelber. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-7146-4675-X (cloth).- ISBN 0-7146-4206-1 (pbk.) 1. Jewish-Arab relations,-1917-1949. 2. Transjordan-Politics and government. 3. Palestine-Politics and government,-1917-1948. I. Tide. DS119.7.G389 1996 956.94'04-dc20 96-27429 CIP All rights reseroed. No part of this publication mt{V be reproduced in any fonn, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior penn iss ion ofthe publisher. Typeset by Vitaset, Paddock Wood, Kent Contents Acknowledgements Vll Abbreviations ix Introduction 1 1 Early Zionist interest in TransJordan 7 I 2 The turning point of the