Changing Dimensions of the Canada-China Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth Making, Juridification, and Parasitical Discourse: a Barthesian Semiotic Demystification of Canadian Political Discourse on Marijuana

MYTH MAKING, JURIDIFICATION, AND PARASITICAL DISCOURSE: A BARTHESIAN SEMIOTIC DEMYSTIFICATION OF CANADIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE ON MARIJUANA DANIEL PIERRE-CHARLES CRÉPAULT Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Daniel Pierre-Charles Crépault, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 ABSTRACT The legalization of marijuana in Canada represents a significant change in the course of Canadian drug policy. Using a semiotic approach based on the work of Roland Barthes, this dissertation explores marijuana’s signification within the House of Commons and Senate debates between 1891 and 2018. When examined through this conceptual lens, the ongoing parliamentary debates about marijuana over the last 127 years are revealed to be rife with what Barthes referred to as myths, ideas that have become so familiar that they cease to be recognized as constructions and appear innocent and natural. Exploring one such myth—the necessity of asserting “paternal power” over individuals deemed incapable of rational calculation—this dissertation demonstrates that the processes of political debate and law-making are also a complex “politics of signification” in which myths are continually being invoked, (re)produced, and (re)transmitted. The evolution of this myth is traced to the contemporary era and it is shown that recent attempts to criminalize, decriminalize, and legalize marijuana are indices of a process of juridification that is entrenching legal regulation into increasingly new areas of Canadian life in order to assert greater control over the consumption of marijuana and, importantly, over the risks that this activity has been semiologically associated with. -

The Harper Casebook

— 1 — biogra HOW TO BECOME STEPHEN HARPER A step-by-step guide National Citizens Coalition • Quits Parliament in 1997 to become a vice- STEPHEN JOSEPH HARPER is the current president, then president, of the NCC. and 22nd Prime Minister of Canada. He has • Co-author, with Tom Flanagan, of “Our Benign been the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Dictatorship,” an opinion piece that calls for an Alberta riding of Calgary Southwest since alliance of Canada’s conservative parties, and 2002. includes praise for Conrad Black’s purchase of the Southam newspaper chain, as a needed counter • First minority government in 2006 to the “monophonically liberal and feminist” • Second minority government in 2008 approach of the previous management. • First majority government in May 2011 • Leads NCC in a legal battle to permit third-party advertising in elections. • Says “Canada is a Northern European welfare Early life and education state in the worst sense of the term, and very • Born and raised in Toronto, father an accountant proud of it,” in a 1997 speech on Canadian at Imperial Oil. identity to the Council for National Policy, a • Has a master’s degree in economics from the conservative American think-tank. University of Calgary. Canadian Alliance Political beginnings • Campaigns for leadership of Canadian Alliance: • Starts out as a Liberal, switches to Progressive argues for “parental rights” to use corporal Conservative, then to Reform. punishment against their children; describes • Runs, and loses, as Reform candidate in 1988 his potential support base as “similar to what federal election. George Bush tapped.” • Resigns as Reform policy chief in 1992; but runs, • Becomes Alliance leader: wins by-election in and wins, for Reform in 1993 federal election— Calgary Southwest; becomes Leader of the thanks to a $50,000 donation from the ultra Opposition in the House of Commons in May conservative National Citizens Coalition (NCC). -

Participaction Launches National Movement to Move Canadians Need to Move More

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ParticipACTION launches national movement to move Canadians need to move more Toronto (ONTARIO) October 15, 2007 – Today, ParticipACTION, the national voice for physical activity and sport participation in Canada, along with its partners including the Government of Canada, celebrated its return with the launch of a public awareness campaign aimed at inspiring Canadians to move more. Originally established in 1971, ParticipACTION was reinvigorated to help deal with the inactivity and obesity crisis that is facing Canada. The launch of the awareness campaign was kicked off by a symbolic walk with the Honourable Tony Clement, Minister of Health, and the Honourable Helena Guergis, Secretary of State, Foreign Affairs and International Trade and Sport, who joined ParticipACTION staff and board members in a stroll from Centre Block to Confederation Building in Ottawa. “There has never been a more critical time for Canadians to get off their couches and get in motion. If we don’t deal with this inactivity crisis, we could soon see a generation of children who have shorter life expectancies than ours. This would be an unprecedented and historical shift,” says Kelly Murumets, President and CEO of ParticipACTION. “Today marks the start of a new movement in Canada – a movement to move. We urge Canadians to join.” ParticipACTION’s public awareness campaign is targeted to all Canadians with an emphasis on parents and Canadian youth. With only nine per cent of Canadian children and youth (aged 5 to 19) meeting the recommended guidelines in Canada’s Physical Activity Guides for Children and Youth1, ParticipACTION’s new ads seek to show the implications of youth inactivity and motivate parents to make physical activity a priority at home. -

Helena Guergis Gets No Sympathy for 'Hissy Fits'

Helena Guergis gets no sympathy for 'hissy fits' Printed: Ottawa Citizen, Friday March 12, 2010 By Jennifer Ditchburn If beleaguered Conservative minister Helena Guergis was hoping for sympathy from her political sisters, former party matriarch Deborah Grey was fresh out. Ms. Guergis, minister of state for the status of women, was a no-show Friday at a panel on women in politics at the Manning Centre's annual conference for small-c conservatives. Her office did not respond to a question about her absence. Two weeks ago, Ms. Guergis was forced to apologize for an angry outburst against airport and Air Canada staff in Charlottetown. She allegedly seethed at being put through airline procedures as she arrived minutes before a scheduled flight, calling the city a “hellhole” and uttering a profanity. Ms. Grey did attend the panel discussion, as did moderator and junior minister Diane Ablonczy, MP Lois Brown and Andrea Mrozek of the Institute for Marriage and Family Canada. When a member of the audience asked about women in politics being treated differently, Ms. Grey responded that even so, it didn't give them licence to “throw hissy fits at airports.” “Women are judged differently. We can like it, we can harangue about it, we can hate it, we can do all kinds of things, but that's the way it is. That's life,” Ms. Grey, one of the best-known Conservative women, later told The Canadian Press. “We can't give ourselves permission to lose control and have a hissy fit at an airport or wherever, in the House of Commons, because it will come back to bite us.” Ms. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

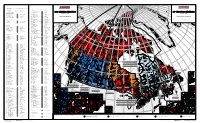

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Core 1..31 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 134 No 134 Friday, October 7, 2005 Le vendredi 7 octobre 2005 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Mitchell La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Mitchell (Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food), seconded by Mr. Brison (ministre de l'Agriculture et de l'Agroalimentaire), appuyé par M. (Minister of Public Works and Government Services), — That Bill Brison (ministre des Travaux publics et des Services S-38, An Act respecting the implementation of international trade gouvernementaux), — Que le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant commitments by Canada regarding spirit drinks of foreign la mise en oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris countries, be now read a second time and referred to the par le Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. étrangers, soit maintenant lu une deuxième fois et renvoyé au Comité permanent de l'agriculture et de l'agroalimentaire. The debate continued. Le débat se poursuit. The question was put on the motion and it was agreed to. La motion, mise aux voix, est agréée. Accordingly, Bill S-38, An Act respecting the implementation En conséquence, le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant la mise en of international trade commitments by Canada regarding spirit oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris par le drinks of foreign countries, was read the second time and referred Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays étrangers, est to the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. -

THE DECLINE of MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY in CANADA by M. KATHLEEN Mcleod Integrated Studies Project Submitted to Dr.Gloria

THE DECLINE OF MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY IN CANADA By M. KATHLEEN McLEOD Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr.Gloria Filax in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta Submitted April 17, 2011 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 The Westminster System of Democratic Government ................................................................... 3 Ministerial Accountability: All the Time, or Only When it is Convenient? ................................... 9 The Richard Colvin Case .................................................................................................................. 18 The Over-Arching Power of the Prime Minister ............................................................................ 24 Michel Foucault and Governmentality ............................................................................................ 31 Governmentality .......................................................................................................................... 31 Governmentality and Stephen Harper ............................................................................................ 34 Munir Sheikh and the Long Form Census ....................................................................................... -

Partie I, Vol. 142, No 11, Édition Spéciale ( 89Ko)

EXTRA Vol. 142, No. 11 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 142, no 11 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, MONDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2008 OTTAWA, LE LUNDI 27 OCTOBRE 2008 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 40th general election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 40e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie Bernard Bigras Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie Bernard Bigras Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Pontiac Lawrence Cannon Pontiac Lawrence Cannon Trinity—Spadina Olivia Chow Trinity—Spadina Olivia Chow Victoria Denise Savoie Victoria Denise Savoie Thornhill Peter Kent Thornhill Peter Kent Edmonton—Mill Woods— Mike Lake Edmonton—Mill Woods— Mike Lake Beaumont Beaumont Edmonton—St. Albert Brent Rathgeber Edmonton—St. Albert Brent Rathgeber Leeds—Grenville Gord Brown Leeds—Grenville Gord Brown Wellington—Halton Hills Michael Chong Wellington—Halton -

Core 1..182 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 9.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 141 Ï NUMBER 162 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, June 1, 2007 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 10023 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, June 1, 2007 The House met at 10 a.m. We all know about the epic battles that have been fought to enable people to exercise their right to vote. Consider women, who, after quite some time, managed to get the right to vote in Canada and Quebec—even later in Quebec than in Canada. Even today, in other Prayers countries, people are forced to fight for the right to vote. And I mean fight physically. Some people have to go to war to bring democracy to their country. I have seen places where armed guards had to GOVERNMENT ORDERS supervise polling stations so that people could vote. So we in Canada are pretty lucky to have the right to vote. Our democracy enables Ï (1005) people to choose who will represent them at various levels of [Translation] government. Unfortunately, there are still places in the world where people cannot do that. CANADA ELECTIONS ACT The House resumed from May 31 consideration of the motion that Bill C-55, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act (expanded voting opportunities) and to make a consequential amendment to the Referendum Act, be read the second time and referred to a committee. -

Scandal Axis:Oversimplified Guide to the Spring Sitting

SCANDAL AXIS: OVERSIMPLIFIED GUIDE TO THE SPRING SITTING KEEP CALM, CARRY ON During the prolonged budget bill vote, Bob Rae rose and confessed to eating three Werther’s hard candies, contrary to House rules. That’s the kind of rule grandparents everywhere can support MPs breaking. Newfoundlanders NDP turncoat Lise St-Denis gave Helena Guergis couldn’t believe their a run for Most Awkward Press Conference Ever ears when they heard when she explained she crossed the floor because Ontario MP Cheryl Jack Layton is dead. But the Liberals have managed to keep her calm and carrying on ever since. Gallant seemingly compare the Ottawa James Moore didn’t River to the Atlantic like the Canadian Ocean during a Museum of Science committee meeting and Technology’s sex on search-and-rescue exhibit, and he wasn’t operations. She quickly afraid to tell them so. clarified her remarks. Dean Del Mastro didn’t think it was science, and he wasn’t afraid to say that either. Thankfully, neither prevented the show from going on. In shockingly frank footage, David Wilks set his constituents straight about the state of democracy, Who forgets to put their phone on silent when they’re spilling the beans challenging the government in question period, twice? on the inner No one, anymore. The footage of one embarrassed workings of party Jack Harris gave us the public service announcement. discipline. He quickly quashed “Oh, you piece of shit!” Justin Trudeau his own rebellion shouted at Peter Kent during a and retreated to the government backbenches. heated question period exchange between the environment minister and Megan Leslie. -

Quantitative Measurement of Parliamentary Accountability Using Text As Data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 by Tanya W

Quantitative measurement of parliamentary accountability using text as data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 by Tanya Whyte A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto c Copyright 2019 by Tanya Whyte Abstract Quantitative measurement of parliamentary accountability using text as data: the Canadian House of Commons, 1945-2015 Tanya Whyte Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2019 How accountable is Canada’s Westminster-style parliamentary system? Are minority parliaments more accountable than majorities, as contemporary critics assert? This dissertation develops a quanti- tative measurement approach to investigate parliamentary accountability using the text of speeches in Hansard, the historical record of proceedings in the Canadian House of Commons, from 1945-2015. The analysis makes a theoretical and methodological contribution to the comparative literature on legislative debate, as well as an empirical contribution to the Canadian literature on Parliament. I propose a trade-off model in which parties balance communication about goals of office-seeking (accountability) or policy-seeking (ideology) in their speeches. Assuming a constant context of speech, I argue that lexical similarity between government and opposition speeches is a valid measure of parlia- mentary accountability, while semantic similarity is an appropriate measure of ideological polarization. I develop a computational approach for measuring lexical and semantic similarity using word vectors and the doc2vec algorithm for word embeddings. To validate my measurement approach, I perform a qualitative case study of the 38th and 39th Parliaments, two successive minority governments with alternating governing parties.