Myth Making, Juridification, and Parasitical Discourse: a Barthesian Semiotic Demystification of Canadian Political Discourse on Marijuana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Anne Millar

Wartime Training at Canadian Universities during the Second World War Anne Millar Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy degree in history Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Anne Millar, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 ii Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the contributions of Canadian universities to the Second World War. It examines the deliberations and negotiations of university, government, and military officials on how best to utilize and direct the resources of Canadian institutions of higher learning towards the prosecution of the war and postwar reconstruction. During the Second World War, university leaders worked with the Dominion Government and high-ranking military officials to establish comprehensive training programs on campuses across the country. These programs were designed to produce service personnel, provide skilled labour for essential war and civilian industries, impart specialized and technical knowledge to enlisted service members, and educate returning veterans. University administrators actively participated in the formation and expansion of these training initiatives and lobbied the government for adequate funding to ensure the success of their efforts. This study shows that university heads, deans, and prominent faculty members eagerly collaborated with both the government and the military to ensure that their institutions’ material and human resources were best directed in support of the war effort and that, in contrast to the First World War, skilled graduates would not be heedlessly wasted. At the center of these negotiations was the National Conference of Canadian Universities, a body consisting of heads of universities and colleges from across the country. -

Industrial Property

ANNUAL SURVEY OF CANADIAN LAW INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY William L. Hayhurst, Q.C. * I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 394 II. RECENT LEGISLATION ................................. 395 III. PROPOSED LEGISLATION ................................ 398 IV . PATENTS ............................................ 399 A. Matters in Which the Patent Office has OriginalJurisdiction ............................... 399 1. Conflicts ...................................... 399 2. Compulsory Licences ............................ 400 3. Subject Matter Capable of Being Patented .......... 401 (a) Printed M atter .............................. 402 (b) Gam es ..................................... 402 (c) Mental Processes and Computer Programs ...... 402 (d) Living M atter ............................... 405 (e) Medical Treatment of Animals and Humans ...... 407 (f) Medical Inventions .......................... 408 (g) The Progeny of Sandoz v. Gilcross ............. 410 (h) Aggregations and Exhausted Combinations ...... 412 (i) Synergism .............................. 412 (ii) M ixtures ............................... 412 (iii) The Aggregative or Unnecessary Addition ... 413 4. D ivision ....................................... 4 15 5. R eissue ....................................... 4 16 6. D isclaimer .................................... 417 B. Substantive Matters in the Courts .................... 418 1. Intervening Rights .............................. 418 2. Personal Liability of Persons in Control of CorporateInfringers ......................... -

Mister Spliffy Pass the Dutchie Mp3, Flac, Wma

Mister Spliffy Pass The Dutchie mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Pass The Dutchie Country: UK Released: 1995 Style: Euro House MP3 version RAR size: 1601 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1155 mb WMA version RAR size: 1864 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 531 Other Formats: DXD AIFF AUD AC3 ASF AU APE Tracklist A Pass The Dutchie (Extended Club Mix) B Pass The Dutchie (Radio Mix) Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Mr. Spliffy* Mr. Spliffy* Featuring CD CHASEX Chase CD CHASEX UK & Featuring Plan Plan B - Pass The 1996 3 Records 3 Europe B Dutchie (CD, Maxi) Sniper Mr. Spliffy* Mr. Spliffy* Featuring Records , 3017242 Featuring Plan Plan B - Pass The 3017242 France 1996 Ramdam B Dutchie (CD, Maxi) Factory Mr. Spliffy* Mr. Spliffy* Featuring 12 CHASEX Chase 12 CHASEX Featuring Plan Plan B - Pass The UK 1996 3 Records 3 B Dutchie (12") Mr. Spliffy* Feat. Plan Mr. Spliffy* 3017246 B - Pass The Dutchie CNR Music 3017246 Europe 1996 Feat. Plan B (12") 12 CHASE Pass The Dutchie Chase 12 CHASE Mister Spliffy UK 1995 X3DJ (Remix) (12", Promo) Records X3DJ Related Music albums to Pass The Dutchie by Mister Spliffy Miss E - Pass That Dutch Balli & The Fat Daddy Featuring Fresh Kid Ice - Master Plan Bob Citrus - Boot The Alarm / Boot The Dutchie Pass Pass - Street Bounce Decemay - Pass The Dutchie Juno & The Dismemberment Plan - Juno & The Dismemberment Plan Molella 's Musical Youth - Pass The Dutchie (Remix) Chase & Status - End Credits VIP / Is It Worth It VIP Deeyah - Sampler From The Forthcoming Album Plan Of My Own Tony Dutchie - Longi Li Li La La. -

Industrial Property Law

INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY LAW G. E. Fisk* I. INTRODUCTION The industrial property survey this year will be restricted to patents, but it is hoped that, next year, sections will be included on trade marks, copyright and industrial design, and unfair competition. The patent cases discussed in this issue are not limited only to last year's, but instead cover the period from 1965 to the end of 1968. A few earlier cases are also discussed, where their inclusion is necessary to show develop- ment of a doctrine.' Some attempt has been made to summarize develop- ments since the writing of any Canadian patent text in rules having general application to patent cases. The survey has been divided into three main headings, namely infringe- ment, validity and reissue. It was originally intended to include a discussion of conflicts and of licence, assignment and devolution, but this has not been done because of space limitation. A case presently pending before the Supreme Court is likely to change conflict practice considerably and it was felt advisable to delay a detailed consideration of this area. Assignment has been covered comprehensively in a recent article by G. F. Henderson, 2 while the problems of licencing encountered in recent cases have dealt mainly with the compulsory licencing provisions relating to pharmaceuticals, which are likely to be modified by a bill now before Parliament. 8 During the period covered by the survey, no new texts on patent law have appeared in Canada, although existing texts are seriously outdated. 4 The only new writing in the field has been in periodicals, notably those pub- lished by The Patent and Trademark Institute of Canada. -

Promise Utility Doctrine and Compatibility Doctrine Under NAFTA: Expropriation and Chapter 11 Considerations

Canada-United States Law Journal Volume 40 Issue 1 Article 8 2016 Promise Utility Doctrine and Compatibility Doctrine Under NAFTA: Expropriation and Chapter 11 Considerations Freedom-Kai Phillips Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj Part of the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Freedom-Kai Phillips, Promise Utility Doctrine and Compatibility Doctrine Under NAFTA: Expropriation and Chapter 11 Considerations, 40 Can.-U.S. L.J. 84 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj/vol40/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canada-United States Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 84 CANADA-UNITED STATES LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40, 2016] PROMISE UTILITY DOCTRINE AND COMPATIBILITY UNDER NAFTA: EXPROPRIATION AND CHAPTER 11 CONSIDERATIONS Freedom-Kai Phillips* ABSTRACT: The 2013 filing by Eli Lilly of a notice of arbitration under Chapter 11 of NAFTA relating to the application of the promise utility doctrine in Canadian jurisprudence brought to light latent tensions relating to domestic patent standards, perceived barriers to innovation, and international investment standards. This paper explores applicable NAFTA obligations and patent regimes in an effort to identify points of convergence and divergence, and argues that the promise utility doctrine while -

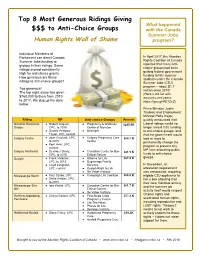

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving What happened $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups with the Canada Summer Jobs Human Rights Wall of Shame program? Individual Members of Parliament can direct Canada In April 2017, the Abortion Summer Jobs funding to Rights Coalition of Canada groups in their ridings. Some reported that many anti- ridings scored consistently choice groups had been getting federal government high for anti-choice grants. funding to hire summer How generous are these students under the Canada ridings to anti-choice groups? Summer Jobs (CSJ) program – about $1.7 Too generous! million since 2010! The top eight alone has given (Here’s the list with $760,000 to them from 2010 amounts and years: to 2017. We dug up the data https://goo.gl/4C1ZsC) below. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Employment Minister Patty Hajdu Riding MP Anti-choice Groups Amount quickly announced that Moncton-Riverview- ● Robert Goguen, ● Pregnancy & Wellness $285.6K Liberal ridings would no Dieppe CPC, to 2015 Centre of Moncton longer award CSJ funding ● Ginette Petitpas- ● Birthright to anti-choice groups, and Taylor, LPC, current that the government would Calgary Centre ● Joan Crockatt, CPC, ● Calgary Pregnancy Care $84.7 K look at ways to to 2015 Centre permanently change the ● Kent Hehr, LPC, program to prevent any current MP from allocating public Calgary Northeast ● Devinder Shory, ● Canadian Centre for Bio- $81.5 K CPC, to 2015 Ethical Reform funds to anti-choice groups. Guelph ● Frank Valeriote, ● Alliance for Life $67.9 K LPC, to 2015 ● Beginnings Family -

The Harper Casebook

— 1 — biogra HOW TO BECOME STEPHEN HARPER A step-by-step guide National Citizens Coalition • Quits Parliament in 1997 to become a vice- STEPHEN JOSEPH HARPER is the current president, then president, of the NCC. and 22nd Prime Minister of Canada. He has • Co-author, with Tom Flanagan, of “Our Benign been the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Dictatorship,” an opinion piece that calls for an Alberta riding of Calgary Southwest since alliance of Canada’s conservative parties, and 2002. includes praise for Conrad Black’s purchase of the Southam newspaper chain, as a needed counter • First minority government in 2006 to the “monophonically liberal and feminist” • Second minority government in 2008 approach of the previous management. • First majority government in May 2011 • Leads NCC in a legal battle to permit third-party advertising in elections. • Says “Canada is a Northern European welfare Early life and education state in the worst sense of the term, and very • Born and raised in Toronto, father an accountant proud of it,” in a 1997 speech on Canadian at Imperial Oil. identity to the Council for National Policy, a • Has a master’s degree in economics from the conservative American think-tank. University of Calgary. Canadian Alliance Political beginnings • Campaigns for leadership of Canadian Alliance: • Starts out as a Liberal, switches to Progressive argues for “parental rights” to use corporal Conservative, then to Reform. punishment against their children; describes • Runs, and loses, as Reform candidate in 1988 his potential support base as “similar to what federal election. George Bush tapped.” • Resigns as Reform policy chief in 1992; but runs, • Becomes Alliance leader: wins by-election in and wins, for Reform in 1993 federal election— Calgary Southwest; becomes Leader of the thanks to a $50,000 donation from the ultra Opposition in the House of Commons in May conservative National Citizens Coalition (NCC). -

Debates of the House of Commons

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION House of Commons Debates Official Report (Hansard) Volume 150 No. 092 Friday, April 30, 2021 Speaker: The Honourable Anthony Rota CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 6457 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, April 30, 2021 The House met at 10 a.m. Bibeau Bittle Blaikie Blair Blanchet Blanchette-Joncas Blaney (North Island—Powell River) Blois Boudrias Boulerice Prayer Bratina Brière Brunelle-Duceppe Cannings Carr Casey Chabot Chagger GOVERNMENT ORDERS Champagne Champoux Charbonneau Chen ● (1000) Cormier Dabrusin [English] Damoff Davies DeBellefeuille Desbiens WAYS AND MEANS Desilets Dhaliwal Dhillon Dong MOTION NO. 9 Drouin Dubourg Duclos Duguid Hon. Chrystia Freeland (Minister of Finance, Lib.) moved Duncan (Etobicoke North) Duvall that a ways and means motion to implement certain provisions of Dzerowicz Easter the budget tabled in Parliament on April 19, 2021 and other mea‐ Ehsassi El-Khoury sures be concurred in. Ellis Erskine-Smith Fergus Fillmore The Deputy Speaker: The question is on the motion. Finnigan Fisher Fonseca Fortier If a member of a recognized party present in the House wishes to Fortin Fragiskatos request either a recorded division or that the motion be adopted on Fraser Freeland division, I ask them to rise in their place and indicate it to the Chair. Fry Garneau Garrison Gaudreau The hon. member for Louis-Saint-Laurent. Gazan Gerretsen Gill Gould [Translation] Green Guilbeault Hajdu Hardie Mr. Gérard Deltell: Mr. Speaker, we request a recorded divi‐ Harris Holland sion. Housefather Hughes The Deputy Speaker: Call in the members. Hussen Hutchings Iacono Ien ● (1045) Jaczek Johns Joly Jones [English] Jordan Jowhari (The House divided on the motion, which was agreed to on the Julian Kelloway Khalid Khera following division:) Koutrakis Kusmierczyk (Division No. -

Core 1..16 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 42e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 22 No 22 Monday, February 22, 2016 Le lundi 22 février 2016 11:00 a.m. 11 heures PRAYER PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Trudeau La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Trudeau (Prime Minister), seconded by Mr. LeBlanc (Leader of the (premier ministre), appuyé par M. LeBlanc (leader du Government in the House of Commons), — That the House gouvernement à la Chambre des communes), — Que la Chambre support the government’s decision to broaden, improve, and appuie la décision du gouvernement d’élargir, d’améliorer et de redefine our contribution to the effort to combat ISIL by better redéfinir notre contribution à l’effort pour lutter contre l’EIIL en leveraging Canadian expertise while complementing the work of exploitant mieux l’expertise canadienne, tout en travaillant en our coalition partners to ensure maximum effect, including: complémentarité avec nos partenaires de la coalition afin d’obtenir un effet optimal, y compris : (a) refocusing our military contribution by expanding the a) en recentrant notre contribution militaire, et ce, en advise and assist mission of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in développant la mission de conseil et d’assistance des Forces Iraq, significantly increasing intelligence capabilities in Iraq and armées canadiennes (FAC) en Irak, en augmentant theatre-wide, deploying CAF medical personnel, -

L'absence De Généraux Canadiens-Français Combattants

Où sont nos chefs? L’absence de généraux canadiens-français combattants durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (1939-1945). Par : Alexandre Sawyer Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales À titre d’exigence partielle en vue de l’obtention d’un doctorat en histoire Université d’Ottawa © Alexandre Sawyer, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 ii RÉSUMÉ Le nombre d’officiers généraux canadiens-français qui ont commandé une brigade ou une division dans l’armée active durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale est presque nul. On ne compte aucun commandant de division francophone dans l’armée outre-mer. Dans les trois premières années de la guerre, seulement deux brigadiers canadiens-français prennent le commandement de brigades à l’entrainement en Grande-Bretagne, mais sont rapidement renvoyés chez eux. Entre 1943 et 1944, le nombre de commandants de brigade francophones passe de zéro à trois. L’absence de généraux canadiens-français combattants (à partir du grade de major-général) durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale s’explique par plusieurs facteurs : le modèle britannique et l’unilinguisme anglais de la milice, puis de l’armée canadienne, mais aussi la tradition anti-impérialiste et, donc, souvent antimilitaire des Canadiens français. Au début de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, aucun officier canadien n’est réellement capable de commander une grande unité militaire. Mais, a-t-on vraiment le choix? Ces officiers sont les seuls dont dispose le Canada. Quand les troupes canadiennes sont engagées au combat au milieu de 1943, des officiers canadiens, plus jeunes et beaucoup mieux formés prennent la relève. À plus petite échelle, le même processus s’opère du côté francophone, mais plus maladroitement. -

Participaction Launches National Movement to Move Canadians Need to Move More

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ParticipACTION launches national movement to move Canadians need to move more Toronto (ONTARIO) October 15, 2007 – Today, ParticipACTION, the national voice for physical activity and sport participation in Canada, along with its partners including the Government of Canada, celebrated its return with the launch of a public awareness campaign aimed at inspiring Canadians to move more. Originally established in 1971, ParticipACTION was reinvigorated to help deal with the inactivity and obesity crisis that is facing Canada. The launch of the awareness campaign was kicked off by a symbolic walk with the Honourable Tony Clement, Minister of Health, and the Honourable Helena Guergis, Secretary of State, Foreign Affairs and International Trade and Sport, who joined ParticipACTION staff and board members in a stroll from Centre Block to Confederation Building in Ottawa. “There has never been a more critical time for Canadians to get off their couches and get in motion. If we don’t deal with this inactivity crisis, we could soon see a generation of children who have shorter life expectancies than ours. This would be an unprecedented and historical shift,” says Kelly Murumets, President and CEO of ParticipACTION. “Today marks the start of a new movement in Canada – a movement to move. We urge Canadians to join.” ParticipACTION’s public awareness campaign is targeted to all Canadians with an emphasis on parents and Canadian youth. With only nine per cent of Canadian children and youth (aged 5 to 19) meeting the recommended guidelines in Canada’s Physical Activity Guides for Children and Youth1, ParticipACTION’s new ads seek to show the implications of youth inactivity and motivate parents to make physical activity a priority at home. -

1930 Heather Mcintyre Thesis Subm

“Man’s Redemption of Man”: Medical Authority and Faith Healers in North America, 1850 - 1930 Heather McIntyre Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Heather McIntyre, Ottawa, Canada, 2020 ii ABSTRACT “Man’s Redemption of Man”: Medical Authority and Faith Healers in North America, 1850 – 1930 Heather McIntyre Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2020 Heather Murray This thesis discusses the various rhetorical, logical, and legal methods the medical profession used to regulate faith healing in North America. In so doing, it illuminates larger questions about the place of religion and authority over the body in modernity. It uses a source base of medical journals, legal documents, and church records to illustrate how doctors positioned themselves as the rational and godly choice for sick people. While faith healing was originally one of many “cures” and kinds of medicine available to North Americans during the 19th century, the medical field rapidly professionalized and supported laws requiring anyone claiming to practice medicine to adhere to one form of scientifically- based medicine. To support this change, physicians used the category of “quackery,” which implies backwardness and superstition, to illustrate the hazards of faith healing and other alternative medicines. Later, the rise of psychology in the 1890s reshaped physicians’ view of faith healing, and they came to explain its claims of success by arguing that “suggestion,” or messages to a person’s unconscious beliefs, can cure particular (gendered) kinds of mental illnesses. Doctors and clergy became curious about the safe use of suggestion, and embarked on experiments like the Emmanuel Movement.