Controlling the Costs of Alternative Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complaint Counsel's Opposition to Renewed Motion to Quash

FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION | OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY | FILED 4/14/2021 | OSCAR NO. 601202PUBLIC | PUBLIC UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES ________________________________________________ In the Matter of HEALTH RESEARCH LABORATORIES, LLC, a limited liability company, WHOLE BODY SUPPLEMENTS, LLC, a limited liability company, and DOCKET NO. 9397 KRAMER DUHON, individually and as an officer of HEALTH RESEARCH LABORATORIES, LLC and WHOLE BODY SUPPLEMENTS, LLC. ______________________________________________ COMPLAINT COUNSEL’S OPPOSITION TO RENEWED MOTION TO QUASH Respondents have made their prior counsel, Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP (“Olshan”), central to this matter by blaming consultants engaged at Olshan’s suggestion for Respondents’ admittedly unlawful advertising. Consequently, what those consultants told Respondents before they chose to run their deceptive advertising is crucial to determining the appropriate scope of relief. Yet Respondents refuse to produce their consultants’ work, and their consultants dubiously claim they no longer possess it. As a result, Complaint Counsel had no choice but to seek this important nonprivileged material from Olshan directly. Respondents claim attorney-client privilege, but their blanket assertion that everything Olshan may possess is allegedly “confidential” does not meet their burden. To prove consulting materials are privileged, Respondents must establish that the consultants worked exclusively to help Olshan provide legal advice, or that they are the “functional equivalent” of Respondents’ own employees. Here, neither is true. Accordingly, because Olshan possesses relevant, nonprivileged documents not available elsewhere, Respondents’ motion must be denied.1 1 Complaint Counsel’s March 30 motion to reschedule the evidentiary hearing to permit more time for discovery is pending before the Commission. -

Timothy Ferris Or James Oberg on 1 David Thomas on Eries

The Bible Code II • The James Ossuary Controversy • Jack the Ripper: Case Closed? The Importance of Missing Information Acupuncture, Magic, i and Make-Believe Walt Whitman: When Science and Mysticism Collide Timothy Ferris or eries 'Taken' James Oberg on 1 fight' Myth David Thomas on oking Gun' Published by the Comm >f Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION off Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAl (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts and Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Health Toronto Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University of Miami Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Oregon Al Hibbs. scientist Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist, MIT Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, execu England Journal of Medicine understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Indiana Univ Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Chicago consumer advocate. Allentown, Pa. and professor of history of science. Harvard Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of Barry Beyerstein.* biopsychologist. -

The Myth of Alpha Consciousness

The Myth of Alpha Consciousness Alpha brain-waves are marketed as a way to produce relaxation, healing, and meditative or occult states. In fact, they are related to activity in the visual system and have no proven curative or paranormal powers. Barry Beyerstein SYCHOPHYSIOLOGY SEEKS to understand how mechanisms in the nervous system mediate consciousness and behavior. Over Pthe years this hybrid field has seen many newly discovered brain processes reportedly linked with unique psychological states only to have further research reveal that the relationship is far more complex than suspected. Correcting these misinterpretations takes time, even in the pro fessional literature. Beyond the lab, it is even more difficult to retire obsolete notions about brain-behavior relationships when the popular press, profit motives, and a host of quasitheological beliefs conspire to perpetuate them. Alpha brain-waves and biofeedback are two areas in which such misapprehensions are legion: In the late 1960s a reawakened interest in altered states of conscious ness was buoyed by claims that patterns in the electroencephalogram (EEG) called "alpha waves" were indicators of meditative or psychic states. This, plus the understandable attraction of anything offering quick relief from anxiety and stress, spawned a multimillion-dollar industry aimed at teach ing people to maximize EEG alpha through a technique called biofeedback. This occurred despite a growing realization among psychophysiologists that the alleged benefits were based upon unsupported assumptions about alpha and despite growing reservations about the efficacy of biofeedback in general. Barry Beyerstein is in the Department of Psychology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia. 42 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER, Vol. -

Yjyjjgl^Ji^Jihildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? the Claims of Aroma .••

NOVA EXAMINES ALIEN ABDUCTIONS • THE WEIRD WORLD WEB • DEBUNKING THE MYSTICAL IN INDIA yjyjjgl^ji^JiHildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? The Claims of Aroma .•• Fun and Fallacies with Numbers I by Marilyn vos Savant le Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT IHf CENIK FOR INQUKY (ADJACENT IO IME MATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director Lee Nisbet. Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock.* psychologist, York Murray Gell-Mann. professor of physics, H. Narasimhaiah, physicist, president, Univ., Toronto Santa Fe Institute; Nobel Prize laureate Bangalore Science Forum, India Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Dorothy Nelkin. sociologist. New York Univ. Albany, Oregon Univ. Joe Nickell.* senior research fellow, CSICOP Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Henry Gordon, magician, columnist. Lee Nisbet.* philosopher, Medaille College Toronto Kentucky James E. Oberg, science writer Stephen Barrett. M.D., psychiatrist, Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Health Sciences Univ. Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Mark Plummer, lawyer, Australia Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., AI Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Canada Laboratory W. V. Quine, philosopher. Harvard Univ. Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Chicago Southern California understanding and cognitive science, Carl Sagan, astronomer. -

Kayla Marie Swanson

What the Puck? The Gentle Wind Project, a Quasi-Religious New Age Alternative Healing Organization by Kayla Marie Swanson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Religious Studies University of Alberta © Kayla Marie Swanson, 2015 ii Abstract The quasi-religious space is important for examining groups and organizations that exhibit qualities of both the sacred and the secular, particularly when groups have a vested interest in being perceived as either secular or sacred. The purpose of this thesis is to examine the Gentle Wind Project, a quasi-religious, New Age alternative healing movement, and to demonstrate how the group fit the category of quasi-religious. First I examined the category of quasi-religion, using Scientology and Transcendental Meditation as two examples of it, followed by examining the religious and secular aspects of Gentle Wind. As part of the examination of Gentle Wind as a quasi-religion, this thesis also briefly explores the role of the internet for Gentle Wind and critics, as well as examines one of the main lawsuits in which the group was involved. Gentle Wind ultimately sued former members and critics over statements made about the group online, and the results of this lawsuit have implications for a long-standing debate within the sociology of religion. This debate revolves around the reliability of former member testimony regarding groups with which they were previously affiliated. In order to conduct my analysis, I followed two research methods. First, I relied heavily on primary source material regarding the Gentle Wind Project, which required me to use an archival methodology. -

William B. Davis-Where There's Smoke

3/695 WHERE THERE’S SMOKE . Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man A Memoir by WILLIAM B. DAVIS ECW Press Copyright © William B. Davis, 2011 Published by ECW Press 2120 Queen Street East, Suite 200, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4E 1E2 416-694-3348 / [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form by any process — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise — without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press. The scanning, uploading, and distribu- tion of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or en- courage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Davis, William B., 1938– Where there’s smoke : musings of a cigarette smoking man : a memoir / William B. Davis. ISBN 978-1-77041-052-7 Also issued as: 978-1-77090-047-9 (pdf); 978-1-77090-046-2 (epub) 1. Davis, William B., 1938-. 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Actors—Canada—Biography. i. Title. PN2287.D323A3 2011 791.4302’8092 C2011-902825-5 Editor: Jennifer Hale 6/695 Cover, text design, and photo section: Tania Craan Cover photo: © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest Photo insert: page 6: photo by Kevin Clark; page 7 (bottom): © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest; page 8: © Fox Broadcasting (Photographer: Carin Baer)/Photofest. All other images courtesy William B. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Rowlands, Barbara Ann (2015). The Emperor's New Clothes: Media Representations Of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13706/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Emperor’s New Clothes: Media Representations of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005 BARBARA ANN ROWLANDS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by prior publication Department of Journalism City University London May 2015 VOLUME I: DISSERTATION CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Declaration 5 Abstract 6 Chapter -

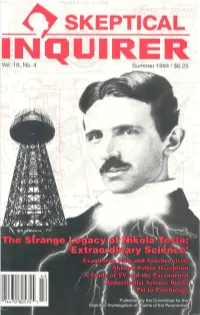

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 1818,, No . 2No. 2 ^^ Winter 1994 Winter / 1994/$6.2$6.255 Paul Kurtz William Grey THE NEW THE PROBLEM SKEPTICISM OF 'PSI' Cancer Scares i*5"***-"" —-^ 44 "74 47CT8 3575" 5 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Asst. Managing Editor Cynthia Matheis. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, "author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. -

FI-Aug-Sept-04.Pdf

THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. We believe in the cultivation of moral excellence. We respect the right to privacy. Mature adults should be allowed to fulfill their aspirations, to express their sexual preferences, to exercise reproductive freedom, to have access to comprehensive and informed health-care, and to die with dignity. -

PAUL KURTZ: When Must Humanists Speak Out? PAUL

PAUL KURTZ: When must humanists speak out? f Celebrating Reason and Humanity SUMMER 2003 • VOL. 23 No. 3 Introductory Price $5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Can. 32> 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

Dawkins, Collins, and the Science-Religion Debate: a New Sociological Study

[ NEWS AND COMMENT Dawkins, Collins, and the Science-Religion Debate: A New Sociological Study DECLAN FAHY A new study appears to dent zoologist Richard Dawkins’s influence as a pub- lic intellectual, arguing that he does not persuade new readers that science and religion are in conflict. But the researchers concluded that biologist Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health and an evangelical Christian, could persuade audiences that science and faith can be compatible. The sociological study, published in Public Understanding of Science, sur- veyed 10,000 Americans to assess in part how scientists who write popular Zoologist and prominent atheist Richard Dawkins (left) and Francis Collins, director of the National books influence public views of reli- Institutes of Health and an evangelical Christian. gion. It identified citizens’ views about the relationship between science and nent stars. In the second, as scholars of religion and tested whether these views Dawkins, in effect, religion have long recognized, atheists changed after learning about Dawkins, gave atheism a have attracted significant personal and author of The God Delusion, and Col- social stigma and have been granted a lins, author of The Language of God: A place in public life. limited space in U.S. public life. Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. Dawkins had earned cultural promi- The study, funded by the philan- nence and a devoted following since the thropic John Templeton Foundation, lead author, said public attitudes to- 1976 publication of The Selfish Gene, which promotes dialogue between ward atheists could explain why Col- but with the 2006 publication of The science and religion, found that more lins had more power than Dawkins to God Delusion he became the embodi- than 21 percent of citizens had heard of sway opinions.