The Myth of Alpha Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cronicon OPEN ACCESS EC PAEDIATRICS Review Article

Cronicon OPEN ACCESS EC PAEDIATRICS Review Article Empathic Communication, its Background and Usefulness in Paediatric Care Cristina Lundqvist-Persson1,2* 1Skaraborg Institute for Research and Development Skövde, Sweden 2Department of Psychology, Lund University, Sweden *Corresponding Author: Cristina Lundqvist-Persson, Skaraborg Institute for Research and Development Skövde and Department of Psychology, Lund University, Sweden. Received: September 15, 2017; Published: October 12, 2017 Abstract Medical care today has made major medical achievements and this is welcome development. However, the development of medi- cal technology has created increasing problems in health care such as distance from the human, the person behind the disease and feelings of inadequacy. This means that we cannot always practice the care and treatment we intended and wished for. The aim with this article is to describe a tool, Empathic Communication, which facilitates understanding the person´s experiences, feelings and needs. Two cases are presented which illustrate, by using the tool Empathic Communication you could increase the quality of care, develop us as helpers, reduce our feelings of inadequacy and awaken the staffs´ sense of meaningfulness at work. Keywords: Empathic Communication; Paediatric Care Introduction A tool of empathic communication Lisbeth Holter Brudal, clinical specialist in psychology, developed in 2004 a tool for empathic communication to be used in health care and schools. After 10 years of practice with the tool, she published a book about the method in Norwegian [1], which was then translated into English [2]. The purpose of this tool Empathic Communication was to “prevent unfortunate consequences of reckless and non- professional com- munication in healthcare and schools.” She also stated that as a dialogue Empathic Communication is a kind of health promotion, because it creates conditions for change, growth and development in interpersonal relationships in general. -

Yjyjjgl^Ji^Jihildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? the Claims of Aroma .••

NOVA EXAMINES ALIEN ABDUCTIONS • THE WEIRD WORLD WEB • DEBUNKING THE MYSTICAL IN INDIA yjyjjgl^ji^JiHildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? The Claims of Aroma .•• Fun and Fallacies with Numbers I by Marilyn vos Savant le Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT IHf CENIK FOR INQUKY (ADJACENT IO IME MATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director Lee Nisbet. Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock.* psychologist, York Murray Gell-Mann. professor of physics, H. Narasimhaiah, physicist, president, Univ., Toronto Santa Fe Institute; Nobel Prize laureate Bangalore Science Forum, India Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Dorothy Nelkin. sociologist. New York Univ. Albany, Oregon Univ. Joe Nickell.* senior research fellow, CSICOP Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Henry Gordon, magician, columnist. Lee Nisbet.* philosopher, Medaille College Toronto Kentucky James E. Oberg, science writer Stephen Barrett. M.D., psychiatrist, Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Health Sciences Univ. Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Mark Plummer, lawyer, Australia Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., AI Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Canada Laboratory W. V. Quine, philosopher. Harvard Univ. Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Chicago Southern California understanding and cognitive science, Carl Sagan, astronomer. -

Kayla Marie Swanson

What the Puck? The Gentle Wind Project, a Quasi-Religious New Age Alternative Healing Organization by Kayla Marie Swanson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Religious Studies University of Alberta © Kayla Marie Swanson, 2015 ii Abstract The quasi-religious space is important for examining groups and organizations that exhibit qualities of both the sacred and the secular, particularly when groups have a vested interest in being perceived as either secular or sacred. The purpose of this thesis is to examine the Gentle Wind Project, a quasi-religious, New Age alternative healing movement, and to demonstrate how the group fit the category of quasi-religious. First I examined the category of quasi-religion, using Scientology and Transcendental Meditation as two examples of it, followed by examining the religious and secular aspects of Gentle Wind. As part of the examination of Gentle Wind as a quasi-religion, this thesis also briefly explores the role of the internet for Gentle Wind and critics, as well as examines one of the main lawsuits in which the group was involved. Gentle Wind ultimately sued former members and critics over statements made about the group online, and the results of this lawsuit have implications for a long-standing debate within the sociology of religion. This debate revolves around the reliability of former member testimony regarding groups with which they were previously affiliated. In order to conduct my analysis, I followed two research methods. First, I relied heavily on primary source material regarding the Gentle Wind Project, which required me to use an archival methodology. -

William B. Davis-Where There's Smoke

3/695 WHERE THERE’S SMOKE . Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man A Memoir by WILLIAM B. DAVIS ECW Press Copyright © William B. Davis, 2011 Published by ECW Press 2120 Queen Street East, Suite 200, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4E 1E2 416-694-3348 / [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form by any process — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise — without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press. The scanning, uploading, and distribu- tion of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or en- courage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Davis, William B., 1938– Where there’s smoke : musings of a cigarette smoking man : a memoir / William B. Davis. ISBN 978-1-77041-052-7 Also issued as: 978-1-77090-047-9 (pdf); 978-1-77090-046-2 (epub) 1. Davis, William B., 1938-. 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Actors—Canada—Biography. i. Title. PN2287.D323A3 2011 791.4302’8092 C2011-902825-5 Editor: Jennifer Hale 6/695 Cover, text design, and photo section: Tania Craan Cover photo: © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest Photo insert: page 6: photo by Kevin Clark; page 7 (bottom): © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest; page 8: © Fox Broadcasting (Photographer: Carin Baer)/Photofest. All other images courtesy William B. -

The Causal Efficacy of Consciousness

entropy Article The Causal Efficacy of Consciousness Matthew Owen 1,2 1 Yakima Valley College, Yakima, WA 98902, USA; [email protected] 2 Center for Consciousness Science, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA Received: 10 June 2020; Accepted: 17 July 2020; Published: 28 July 2020 Abstract: Mental causation is vitally important to the integrated information theory (IIT), which says consciousness exists since it is causally efficacious. While it might not be directly apparent, metaphysical commitments have consequential entailments concerning the causal efficacy of consciousness. Commitments regarding the ontology of consciousness and the nature of causation determine which problem(s) a view of consciousness faces with respect to mental causation. Analysis of mental causation in contemporary philosophy of mind has brought several problems to the fore: the alleged lack of psychophysical laws, the causal exclusion problem, and the causal pairing problem. This article surveys the threat each problem poses to IIT based on the different metaphysical commitments IIT theorists might make. Distinctions are made between what I call reductive IIT, non-reductive IIT, and non-physicalist IIT, each of which make differing metaphysical commitments regarding the ontology of consciousness and nature of causation. Subsequently, each problem pertaining to mental causation is presented and its threat, or lack thereof, to each version of IIT is considered. While the lack of psychophysical laws appears unthreatening for all versions, reductive IIT and non-reductive IIT are seriously threatened by the exclusion problem, and it is difficult to see how they could overcome it while maintaining a commitment to the causal closure principle. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Rowlands, Barbara Ann (2015). The Emperor's New Clothes: Media Representations Of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13706/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Emperor’s New Clothes: Media Representations of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005 BARBARA ANN ROWLANDS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by prior publication Department of Journalism City University London May 2015 VOLUME I: DISSERTATION CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Declaration 5 Abstract 6 Chapter -

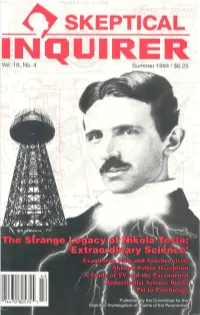

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 1818,, No . 2No. 2 ^^ Winter 1994 Winter / 1994/$6.2$6.255 Paul Kurtz William Grey THE NEW THE PROBLEM SKEPTICISM OF 'PSI' Cancer Scares i*5"***-"" —-^ 44 "74 47CT8 3575" 5 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Asst. Managing Editor Cynthia Matheis. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, "author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. -

Effects of a Focused Breathing Mindfulness Exercise on Attention, Memory, and Mood: the Importance of Task Characteristics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Universidad de Zaragoza Effects of a Focused Breathing Mindfulness Exercise on Attention, Memory, and Mood: The Importance of Task Characteristics Nikolett Eisenbeck,1,2 Carmen Luciano1 and Sonsoles Valdivia-Salas3 1 Department of Psychology, University of Almer´ıa, Almer´ıa, Spain 2 Karoli Gaspar University of the Reformed Church in Hungary 3 Department of Psychology, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain Previous research has shown that long-term mindfulness training has beneficial effects on cognitive functioning and emotional regulation, but results are mixed regarding single mindfulness exercises, especially on attention and memory tasks. Thus, the present study aimed to analyse the effects of the Focused Breathing Exer- cise (FB) on cognitive performance, using standardised tests. Forty-six healthy un- dergraduate students were randomly assigned either to a FB or a Control condition. Two cognitive tasks (the Concentrated Attention task of the Toulouse-Pierron Factorial Battery and the Logical Memory Subtest I from the Wechsler Memory Scale III), along with mood evaluations (the Positive and Negative Affect Scale), were implemented both before and after the interventions. Results showed no sig- nificant differences for the attention task and mood evaluations. Nonetheless, the FB enhanced performance for the memory task significantly more than the Control exercise. The findings highlight that mindfulness does not affect equally all -

Affect Integration and Attachment in Children and Youth: Conceptual

International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 2018, 18, 1, 65-82 Printed in Spain. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2018 AAC Affect Integration and Attachment in Children and Youth: Conceptual Issues -Implications for Practice and Research Eva Taarvig* Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital, Norway Ole Andrè Solbakken University of Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT The essential role of affect and emotion in human behavior, motivation, cognition, and interpersonal interaction is emphasized in various efforts to understand how children develop. However, various theoretical traditions have focused on different features. In this article we focus on the views in attachment theory and the affect consciousness (AC) model/related affect integration perspectives. The attachment theory and the AC perspective/related affect integration perspectives are widely recognized approaches that explicitly focus on the role of affect, cognition, and behavior in the context of others as the main areas in both children’s developmental processes and psychotherapeutic processes. However, these traditions represent both overlapping and contrasting views. On this background we discuss the following questions: 1. How does attachment theory describe the view on affect/emotion, motivation, cognition, and interpersonal interaction, and how do the AC perspective/related affect integration perspectives describe the view on the same subjects? What central theoretical similarities and differences do we find when we compare AC and attachment theory? 2. What role does AC play in attachment, and what role does attachment play in AC? 3. Can the AC perspective/related affect integration perspectives expand and provide nuance to our understanding of the role of affect and emotion in attachment theory, including an understanding of typical and nontypical emotional learning processes? We identified six central AC aspects that can expand our understanding of the function and role of affect and emotion in attachment theory. -

Course Syllabus NOTE

Course Syllabus NOTE: This syllabus is subject to change during the semester. Please check this syllabus on a regular basis for any updates. Department : Psychology Course Title : General Psychology Section Name : 2301.49 Start Date : 01/17/2012 End Date : 05/11/2012 Modality : Face to face Credits : 3 Instructor Information Name : Kelie Jones OC Email : [email protected] OC Phone # : 432-335-6308 OC Office : Wilkerson Hall room 233 Course Description Presents a basic understanding of Psychological terms, theories, and methodologies in the scientific discipline that studies behavior and mental processes. Cognitive abilities such as problem solving, decision-making, and communication, affective states like building self-esteem, and sociability, and behavioral events where one participates as a group member are explored. Information acquisition, interpretation, and communication of a psychological nature are the basis on which this course is predicated. In this way, psychological principles are understandable in the context of biology, the brain, neurotransmitters and hormones, personality theory, learning principles, lifespan development, relationships, abnormal psychology and therapies. A wide application of a variety of topics is the focus of this introductory course. Prerequisites/Co requisites None _____________________________________________________________________________ Scans SCANS 5, 6, 9, 10, and 11. _____________________________________________________________________________ Course Objectives Define psychology and its four primary goals.* Explain the origins of psychology and the seven major perspectives that have emerged from its study.* Describe the scientific method and key ethical issues in psychological research.* Describe the advantages and disadvantages of four research methods.* Describe and define neurons and how they communicate information. * Describe the organization of the central and peripheral nervous system. -

The Buddhist Perspective of Interpritivism As a Philosophical Base for Social Science Research

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 The Buddhist Perspective of Interpritivism as a Philosophical Base for Social Science Research MM Jayawardena1, WAAK Amaratunga2 1PhD (Colombo), MA (Peradeniya), BA Hons in Economics (Peradeniya), Dip in Psychology and Counselling (SLNIPC) 2MPhil (Kelaniya), MA in Linguistics (Kelaniya), BA Hons in English (Peradeniya), Faculty of Management, Social Sciences and Humanities, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka Abstract: The practicability and the deliverability of research outcomes in social sciences have been rather questionable. In this context, interpretivism has become popular in social science research as it enables to capture more crucial qualitative information, which is based on inferences of sensory expressions rather than on direct information gathered through sensory organs. Although qualitative information cannot be numerically assessed, it is important in the deliverability of research outcomes. So, interpretivists believe that through a study of individual inferences, the reality of the research context can be better captured as it goes in-depth into the research issue while digging into the roots of individual human behaviour. Therefore, interpretivists argue that they can reach practicable outcomes that deliver a valid contribution at individual level as well as at societal level. On the other hand, some argue that as interpretivism does not have a constructive and strong theoretical base like in positivism, the research outcomes become subjective and less scientific. Addressing this criticism, Max Weber articulated "verstehen" (intuitive doctrine) and the "Ideal Type" referring to the society of the research context focused on by the researcher.