Kayla Marie Swanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HINDUISM in EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts

HINDUISM IN EUROPE Stockholm 26-28 April, 2017 Abstracts 1. Vishwa Adluri, Hunter College, USA Sanskrit Studies in Germany, 1800–2015 German scholars came late to Sanskrit, but within a quarter century created an impressive array of faculties. European colleagues acknowledged Germany as the center of Sanskrit studies on the continent. This chapter examines the reasons for this buildup: Prussian university reform, German philological advances, imagined affinities with ancient Indian and, especially, Aryan culture, and a new humanistic model focused on method, objectivity, and criticism. The chapter’s first section discusses the emergence of German Sanskrit studies. It also discusses the pantheism controversy between F. W. Schlegel and G. W. F. Hegel, which crucially influenced the German reception of Indian philosophy. The second section traces the German reception of the Bhagavad Gītā as a paradigmatic example of German interpretive concerns and reconstructive methods. The third section examines historic conflicts and potential misunderstandings as German scholars engaged with the knowledge traditions of Brahmanic Hinduism. A final section examines wider resonances as European scholars assimilated German methods and modeled their institutions and traditions on the German paradigm. The conclusion addresses shifts in the field as a result of postcolonial criticisms, epistemic transformations, critical histories, and declining resources. 2. Milda Ališauskienė, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania “Strangers among Ours”: Contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania This paper analyses the phenomenon of contemporary Hinduism in Lithuania from a sociological perspective; it aims to discuss diverse forms of Hindu expression in Lithuanian society and public attitudes towards it. Firstly, the paper discusses the history and place of contemporary Hinduism within the religious map of Lithuania. -

Conference Handbook ICSA 2010 Annual International Conference: Psychological Manipulation, Cultic Groups, and Harm

Conference Handbook ICSA 2010 Annual International Conference: Psychological Manipulation, Cultic Groups, and Harm With the collaboration of Info-Cult/Info-Secte, Montreal, Canada July 1-3, 2010 Doubletree at George Washington Bridge 2117 Route 4 East, Fort Lee, NJ International Cultic Studies Association PO Box 2265 Bonita Springs, FL 34133 239-514-3081 www.icsahome.com Welcome Welcome to the 2010 International Cultic Studies Association (ICSA) conference, Psychological Manipulation, Cultic Groups, and Harm. Speakers have given much of their time in order to present at this conference. Many attendees have come long distances and have diverse backgrounds. Hence, please help us begin sessions on time and maintain a respectful tone during the sometimes lively and provocative discussions. This is a public conference. If you have matters that are sensitive or that you prefer to keep confidential, you should exercise appropriate care. Private audio- or videotaping is not permitted. We hope to make some videos and/or audios available after the conference. Press who attend the conference may come from mainstream and nonmainstream, even controversial, organizations. If a journalist seeks to interview you, exercise appropriate care. If you desire to refuse an interview request, feel free to do so. Remember, if you give an interview, you will have no control over what part of the interview, if any, will be used. ICSA conferences try to encourage dialogue and are open to diverse points of view. Hence, opinions expressed at the conference or in books and other materials available in the bookstore should be interpreted as opinions of the speakers or writers, not necessarily the views of ICSA or its staff, directors, or advisors. -

The Myth of Alpha Consciousness

The Myth of Alpha Consciousness Alpha brain-waves are marketed as a way to produce relaxation, healing, and meditative or occult states. In fact, they are related to activity in the visual system and have no proven curative or paranormal powers. Barry Beyerstein SYCHOPHYSIOLOGY SEEKS to understand how mechanisms in the nervous system mediate consciousness and behavior. Over Pthe years this hybrid field has seen many newly discovered brain processes reportedly linked with unique psychological states only to have further research reveal that the relationship is far more complex than suspected. Correcting these misinterpretations takes time, even in the pro fessional literature. Beyond the lab, it is even more difficult to retire obsolete notions about brain-behavior relationships when the popular press, profit motives, and a host of quasitheological beliefs conspire to perpetuate them. Alpha brain-waves and biofeedback are two areas in which such misapprehensions are legion: In the late 1960s a reawakened interest in altered states of conscious ness was buoyed by claims that patterns in the electroencephalogram (EEG) called "alpha waves" were indicators of meditative or psychic states. This, plus the understandable attraction of anything offering quick relief from anxiety and stress, spawned a multimillion-dollar industry aimed at teach ing people to maximize EEG alpha through a technique called biofeedback. This occurred despite a growing realization among psychophysiologists that the alleged benefits were based upon unsupported assumptions about alpha and despite growing reservations about the efficacy of biofeedback in general. Barry Beyerstein is in the Department of Psychology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia. 42 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER, Vol. -

Yjyjjgl^Ji^Jihildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? the Claims of Aroma .••

NOVA EXAMINES ALIEN ABDUCTIONS • THE WEIRD WORLD WEB • DEBUNKING THE MYSTICAL IN INDIA yjyjjgl^ji^JiHildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? The Claims of Aroma .•• Fun and Fallacies with Numbers I by Marilyn vos Savant le Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT IHf CENIK FOR INQUKY (ADJACENT IO IME MATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director Lee Nisbet. Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock.* psychologist, York Murray Gell-Mann. professor of physics, H. Narasimhaiah, physicist, president, Univ., Toronto Santa Fe Institute; Nobel Prize laureate Bangalore Science Forum, India Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Dorothy Nelkin. sociologist. New York Univ. Albany, Oregon Univ. Joe Nickell.* senior research fellow, CSICOP Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Henry Gordon, magician, columnist. Lee Nisbet.* philosopher, Medaille College Toronto Kentucky James E. Oberg, science writer Stephen Barrett. M.D., psychiatrist, Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Health Sciences Univ. Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Mark Plummer, lawyer, Australia Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., AI Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Canada Laboratory W. V. Quine, philosopher. Harvard Univ. Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Chicago Southern California understanding and cognitive science, Carl Sagan, astronomer. -

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. “How is the field of psychotherapy to become progressively more informed by the infinite wisdom of spirit? It will happen through individuals who allow their own lives to be transformed—their own inner source of knowing to be awakened and expressed.” —Yogi Amrit Desai NOTE: See also the “Counseling” bibliography. For eating disorders, please see the “Eating Disorders” bibliography, and for PTSD, please see the “PTSD” bibliography. Books and Dissertations Abegg, Emil. Indishche Psychologie. Zürich: Rascher, 1945. [In German.] Abhedananda, Swami. The Yoga Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1960, 1983. “This volume comprises lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda before a[n] . audience in America on the subject of [the] Yoga-Sutras of Rishi Patanjali in a systematic and scientific manner. “The Yoga Psychology discloses the secret of bringing under control the disturbing modifications of mind, and thus helps one to concentrate and meditate upon the transcendental Atman, which is the fountainhead of knowledge, intelligence, and bliss. “These lectures constitute the contents of this memorial volume, with copious references and glossaries of Vyasa and Vachaspati Misra.” ___________. True Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1982. “Modern Psychology does not [address] ‘a science of the soul.’ True Psychology, on the other hand, is that science which consists of the systematization and classification of truths relating to the soul or that self-conscious entity which thinks, feels and knows.” Agnello, Nicolò. -

William B. Davis-Where There's Smoke

3/695 WHERE THERE’S SMOKE . Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man A Memoir by WILLIAM B. DAVIS ECW Press Copyright © William B. Davis, 2011 Published by ECW Press 2120 Queen Street East, Suite 200, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4E 1E2 416-694-3348 / [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form by any process — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise — without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press. The scanning, uploading, and distribu- tion of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or en- courage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Davis, William B., 1938– Where there’s smoke : musings of a cigarette smoking man : a memoir / William B. Davis. ISBN 978-1-77041-052-7 Also issued as: 978-1-77090-047-9 (pdf); 978-1-77090-046-2 (epub) 1. Davis, William B., 1938-. 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Actors—Canada—Biography. i. Title. PN2287.D323A3 2011 791.4302’8092 C2011-902825-5 Editor: Jennifer Hale 6/695 Cover, text design, and photo section: Tania Craan Cover photo: © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest Photo insert: page 6: photo by Kevin Clark; page 7 (bottom): © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest; page 8: © Fox Broadcasting (Photographer: Carin Baer)/Photofest. All other images courtesy William B. -

Essence of Yoga

ESSENCE OF YOGA By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA 6(59(/29(*,9( 385,)<0(',7$7( 5($/,=( Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION Thirteenth Edition: 1988 (5000 Copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition : 1998 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7052-024-x Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. PUBLISHERS’ NOTE Even among the inspiring books of Sri Gurudev, this is a unique book. It was written with the special intention of having the entire matter recorded on the gramophone disc. For this purpose Gurudev had given in this book the very essence of his own teachings. Hence, this book was chosen for being sent to every new member of the Divine Life Society on enrolment. It is, as it were, the ‘Beginner’s Guide to Divine Life’. Members of the Divine Life Society and spiritual aspirants have added this precious volume to the scriptures which they study daily as Svadhyaya and have derived incalculable benefit by the assimilation of these teachings into their daily life. This text containing, a valuable treasure of wisdom is placed in the hands of aspirants all over the world in the fervent hope that it will guide them to the great goal of human life, viz., God-realisation. —THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY iii UNIVERSAL PRAYER Thou art, O Lord! The creator of this universe. -

The OTO Phenomenon Peter-Robert König

Theosophical History A Quarterly Journal of Research Volume IV, No. 3 July 1992 ISSN 0951-497X THEOSOPHICAL HISTORY A Quarterly Journal of Research Founded by Leslie Price, 1985 Volume IV, No. 3, July 1992 The subscription fee for the journal is $14.00 (U.S., Mexico, EDITOR Canada), $16.00 (elsewhere), or $24.00 (air Mail) for four issues a year. single issues are $4.00. All inquiries should be sent to James James A. Santucci Santucci, Department of Religious Studies, California State Uni- California State University, Fullerton versity, Fullerton, CA 92634-9480 (U.S.A.). The Editors assume no responsibility for the views expressed by ASSOCIATE EDITORS authors in Theosophical History. Robert Boyd * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * John Cooper GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION OF MANUSCRIPTS University of Sydney 1 The final copy of all manuscripts must be submitted on 8 ⁄2 x11 April Hejka-Ekins 1 inch paper, double-spaced, and with margins of at least 1 ⁄4 inches California State University, Stanislaus on all sides. Words and phrases intended for italics output should be underlined in the manuscript. The submitter is also encouraged to Jerry Hejka-Ekins submit a floppy disk of the work in ASCII or WordPerfect 5 or 5.1, in Nautilus Books 1 an I.B.M. or compatible format. If possible, Macintosh 3 ⁄2 inch disk files should also be submitted, saved in ASCII (“text only with line Robert Ellwood breaks” format if in ASCII), Microsoft Word 4.0–5.0, or WordPerfect. University of Southern California We ask, however, that details of the format codes be included so that we do not have difficulties in using the disk. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Rowlands, Barbara Ann (2015). The Emperor's New Clothes: Media Representations Of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13706/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Emperor’s New Clothes: Media Representations of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005 BARBARA ANN ROWLANDS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by prior publication Department of Journalism City University London May 2015 VOLUME I: DISSERTATION CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Declaration 5 Abstract 6 Chapter -

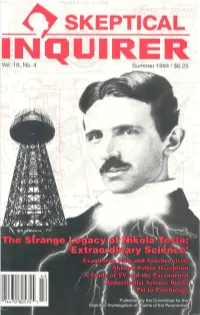

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Agni Yoga Carol Parrish-Harra

Spring 2007 A Way for the Courageous: Agni Yoga Carol Parrish-Harra Summary lives and to guide others by example into an understanding of principles of transformation. gni Yoga calls for a disciple with a spe- A cific kind of consciousness with ready Agni Yoga suggests for the self-disciplined will and fiery determination. In this most disciple of today that it is not enough to be modern approach one’s own inner presence is obedient, but that self-actualization is the real developed through continual evaluation of per- challenge. While the teaching suggests, yes, sonal dedication and self-discipline, heart and indeed, we need a mentor and the discipline mind. Natural within the approach are such that such affords, our real work is to recognize challenges as equality for the churched and the significance of the self within, called by unchurched, respect for eastern and western whatever name. Themes important to the eth- practices, and an ever widening loyalty to ics of the path of initiation are used as major one’s own inner authority. guidelines. Thus, we challenge ourselves to live within the perimeter of the embraced Herein glimpses of the lives of Russian devo- themes rather than simple straight rules. In tees as they anchor the teachings in the midst this way each must proceed as they can, apply- of heavy work-a-day duties. Passionate infor- ing self-regulatory actions to daily experience. mation regarding the role of women is deliv- Discrimination is demanded in keeping with ered by the Spiritual Hierarchy and recorded the Agni themes for enlightenment while by Helena Roerich. -

Teachings of Helena Roerich and Geoffrey Hodson John Nash

Winter 2006 The World Mother: Teachings of Helena Roerich and Geoffrey Hodson John Nash Abstract like Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891), Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), Myrtle Page mong the wealth of insights contributed Fillmore (1845–1931), and Violet Mary Firth A by Helena Roerich and Geoffrey Hodson (1890–1946),1 who launched major religious were important teachings about the divine initiatives or became influential esoteric teach- feminine individuality known as the World ers. Many other women have followed in their Mother. This article explores the two authors’ footsteps. teachings and compares them with each other, with eastern and western religious beliefs, and The new awareness of the Divine Feminine with contributions from other writers of the and the emergence of these women teachers last 100 years. can scarcely be considered unrelated develop- ments. This is not to say that all significant The major thrust of Roerich’s and Hodson’s teachings on the Divine Feminine have come teachings is that the World Mother has mani- from women. Nor would it be true to say that fested many times over the millennia, most the new awareness was simply an offshoot of recently as Mary, the mother of Christ. It is the feminist movement; its scope has been suggested that “World Mother” is in fact an considerably more general. Male authors have office, part of a hierarchy extending from made major contributions, and large numbers planetary to cosmic levels, which has been of men have reported favorably on the expan- held by a succession of entities. The office- sion in their own awareness of the divine na- holders align themselves with the deva evolu- ture.