Chapter Twenty Four Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:40 PM - 4:00 PM Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J. Taylor Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons Taylor, Joshua J., "Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 4. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/4 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century What does it mean to be Russian? In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian nobility was engrossed with French culture. According to Dr. Marina Soraka and Dr. Charles Ruud, “Russian nobility [had a] weakness for the fruits of French civilization.”1 When Peter the Great came into power in 1682-1725, he forced Western ideals and culture into the very way of life of the aristocracy. “He wanted to Westernize and modernize all of the Russian government, society, life, and culture… .Countries of the West served as the emperor’s model; but the Russian ruler also tried to adapt a variety of Western institutions to Russian needs and possibilities.”2 However, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in 1812, he threw the pro- French aristocracy in Russia into an identity crisis. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 171 International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2017) M. I. Glinka’s Opera A Life for the Tzar: a Historical- Archaeological Perspective of Research Yevgeniy Levashev State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Nadezhda Teterina State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Yelena Shcheboleva State Institute for Art Studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The scientific matter, which is associated with (the day of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov’s coronation at the name of a real historical person, but somewhat the Moscow Kremlin)1 . mythologized folk hero, the peasant Ivan Susanin, has been discussed in many dozens of books and hundreds of articles in When approached superficially, the development of various fields of domestic Humanities. Among them, a action in Glinka’s opera may seem overloaded with blatant significant part of this research is musicology, which is the key contradictions. They were especially visible in the value in the history of Russian music opera masterpiece by sumptuous theatrical productions of the nineteenth century. Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka. The objective of this article consists consequently in an attempt to show how naturally the musical Indeed, the scene of Polish ball, at which a typical figure drama is associated with the creatively comprehended system of Catholic cardinal is present, gives rise to the following of historical facts in the opera “A Life for the Tsar”. perplexing question: how the Polish soldiers, despite the cruel Russian frost, could reach the distant village of Keywords—Opera “A Life for the Tsar”, Ivan Susanin, tsar Domnino without having noticed on their way neither Mikhail Romanov, Russia and Polish-Lithuanian Smolensk, nor Moscow, nor else Yaroslavl’ or Kostroma. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

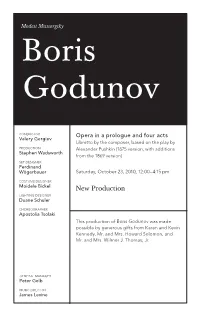

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

The World of Child Psychology in Early Mussorgsky's Works

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 10, NO. 4, 3436-3449 OPEN ACCESS The World of Child Psychology in Early Mussorgsky’s Works Iza A. Nemirovskayaa, Lyudmila S. Bakshia, Olga V. Gromovaa, Irina A. Korsakovaa, and Alexander S. Bazikovb aMoscow state Institute of music named after A. G Schnitke, Moscow, RUSSIA; bGnessin Russian Academy of Music, Moscow, RUSSIA ABSTRACT The world of a child as a topic gave birth to a number of Mussorgsky`s decisions concerning figurative modes, music style systems, principles of composition and music poetics. The master captured the microcosm of passions, that originally inhabit the soul of a child, and his works presented an embodiment of the deep, ontological nature of any human personality with its typical mixture of good and evil. In his musical works about children the composer also showed us some fundamental laws of psychology: some child entertainments, that are not quite harmless, conceal future repulsive character traits of an adult; and evident aggressiveness of a person is often a result of a former child having been unjustly insulted. All this makes it possible for us to speak of Mussorgsky as a composer and a child psychologist. KEYWORDS ARTICLE HISTORY Mussorgsky, childhood, psychology, poetics Received 3 May 2016 Revised 13 July 2016 Accepted 22 July 2016 Introduction The interest of Mussorgsky to the world of a child was intrinsic to his soul capable of understanding children and evoking their love in response. Lonely in his soul, he had a trusting heart, openness and sincerity that are characteristic to children. A.N. -

Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/98 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Wendy Rosslyn is Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Nottingham, UK. Her research on Russian women includes Anna Bunina (1774-1829) and the Origins of Women’s Poetry in Russia (1997), Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women Writers 1763- 1825 (2000) and Deeds not Words: The Origins of Female Philantropy in the Russian Empire (2007). Alessandra Tosi is a Fellow at Clare Hall, Cambridge. Her publications include Waiting for Pushkin: Russian Fiction in the Reign of Alexander I (1801-1825) (2006), A. M. Belozel’skii-Belozerskii i ego filosofskoe nasledie (with T. V. Artem’eva et al.) and Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825 (2007), edited with Wendy Rosslyn. Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture Edited by Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial