Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information About the Authors

Ярославский педагогический вестник – 2015 – № 6 INFORMATION ABOUT THE AUTHORS Abaturova Vera Sergeevna – Candidate of Peda- Belkina Tamara Leonidovna – Candidate of gogical Sciences, Head of the Educational and In- Philosophic Sciences, Associate Professor, Professor formation Technologies Department of the Southern of the Philosophy and Political Science Department Mathematical Institute of Vladikavkaz Scientific of FSBEI HPE «Kostroma State University named Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Re- after N. A. Nekrasov». 156961, Kostroma, 1-st May public of Noth Ossetia – Alania. 362027, Vladikav- Street, 14. kaz, Markus Street, 22. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Belova Irina Sergeevna – Candidate of Philo- Azov Andrey Vadimovich – Doctor of Philosoph- sophic Sciences, Professor of the General Humani- ic Sciences, Professor, Head of the Philosophy De- ties and Study of Theatre Department of FSBEI HPE partment of FSBEI HPE «Yaroslavl State Pedagogi- «Yaroslavl State Theatrical Institute». 150000, Ya- cal University named after K. D. Ushinsky». roslavl, Pervomayskaya Street, 43. 150000, Yaroslavl, Respublikanskaya Street, 108. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Budakhina Nadezhda Leonidovna – Candidate Bazikov Mikhail Vasilievich – an applicant of of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor of the the General and Social Psychology Department of Economics and Management Department of FSBEI FSBEI HPE «Yaroslavl State Pedagogical Universi- HPE «Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University -

Zhenotdel, Russian Women and the Communist Party, 1919-1930

RED ‘TEASPOONS OF CHARITY’: ZHENOTDEL, RUSSIAN WOMEN AND THE COMMUNIST PARTY, 1919-1930 by Michelle Jane Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Michelle Jane Patterson 2011 Abstract “Red ‘Teaspoons of Charity’: Zhenotdel, the Communist Party and Russian Women, 1919-1930” Doctorate of Philosophy, 2011 Michelle Jane Patterson Department of History, University of Toronto After the Bolshevik assumption of power in 1917, the arguably much more difficult task of creating a revolutionary society began. In 1919, to ensure Russian women supported the Communist party, the Zhenotdel, or women’s department, was established. Its aim was propagating the Communist party’s message through local branches attached to party committees at every level of the hierarchy. This dissertation is an analysis of the Communist party’s Zhenotdel in Petrograd/ Leningrad during the 1920s. Most Western Zhenotdel histories were written in the pre-archival era, and this is the first study to extensively utilize material in the former Leningrad party archive, TsGAIPD SPb. Both the quality and quantity of Zhenotdel fonds is superior at St.Peterburg’s TsGAIPD SPb than Moscow’s RGASPI. While most scholars have used Moscow-centric journals like Kommunistka, Krest’ianka and Rabotnitsa, this study has thoroughly utilized the Leningrad Zhenotdel journal Rabotnitsa i krest’ianka and a rich and extensive collection of Zhenotdel questionnaires. Women’s speeches from Zhenotdel conferences, as well as factory and field reports, have also been folded into the dissertation’s five chapters on: organizational issues, the unemployed, housewives and prostitutes, peasants, and workers. -

New Records of Lichens and Allied Fungi from the Kostroma Region, Russia

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 56: 53–62 (2019) https://doi.org/10.12697/fce.2019.56.06 New records of lichens and allied fungi from the Kostroma Region, Russia Irina Urbanavichene1 & Gennadii Urbanavichus2 1Komarov Botanical Institute RAS, Professor Popov Str. 2, 197376 St Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Institute of North Industrial Ecology Problems, Kola Science Centre RAS, Akademgorodok 14a, 184209 Apatity, Murmansk Region, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: 29 species of lichens, 3 non-lichenized calicioid fungi and 3 lichenicolous fungi are reported for the first time from the Kostroma Region. Among them, 15 species are new for the Central Federal District, including Myrionora albidula – a rare species with widely scattered locations, previously known only from the Southern Urals Mts in European Russia. The most important discoveries are confined to old-growth coniferous Picea sp. and Abies sibirica forests in the Kologriv Forest Nature Reserve. Two species (Leptogium burnetiae and Menegazzia terebrata) are included in the Red Data Book of Russian Federation. The distribution, ecology, taxonomic characters and conservation status of rare species and of those new for the Central Federal District are provided. Keywords: Biatora mendax, Myrionora albidula, old-growth forests, southern taiga, Kologriv Forest Reserve, Central European Russia INTRODUCTION The Kostroma Region is a large (60,211 km2), berniya, listing 39 and 54 taxa, respectively. most northeastern part of the Central Federal The recent published additions to the Kostroma District in European Russia situated between lichen flora are from the Kologriv District by Ivanovo, Yaroslavl, Vologda, Kirov and Nizhniy Novgorod regions (Fig. -

Download Full Text

www.ssoar.info The evolution of peasant economy in the industrial center of Russia at the end of the XIXth - beginning of the XXth century: (according to the Zemstvo statistical data) Ossokina, H.; Satarov, G. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Ossokina, H., & Satarov, G. (1991). The evolution of peasant economy in the industrial center of Russia at the end of the XIXth - beginning of the XXth century: (according to the Zemstvo statistical data). Historical Social Research, 16(2), 74-89. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.16.1991.2.74-89 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-33259 Historical Social Research, Vol. 16 — 1991 — No. 2, 74-89 The Evolution of Peasant Economy in the Industrial Center of Russia at the End of the XlXth - Beginning of the XXth Century (According to the Zemstvo Statistical Data) H. Ossokina, G. Satarov* Abstract: The dispute on Russian agrarian capitalism is a century old. The authors' aim is to reveal and to ana• lyse the factors which determined the evolution of pea• sant economy in the Industrial Center on the turn of the century. -

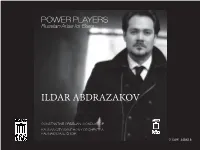

Ildar Abdrazakov

POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR KAUNAS CITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KAUNAS STATE CHOIR 1 0 13491 34562 8 ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL iconic characters The dynamics of power in Russian opera and its most DE 3456 (707) 996-3844 • © 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., © 2013 Delos Productions, 95476-9998 CA Sonoma, 343, Box P.O. (800) 364-0645 [email protected] www.delosmusic.com CONSTANTINE ORBELIAN, CONDUCTOR ORBELIAN, CONSTANTINE ORCHESTRA CITY SYMPHONY KAUNAS CHOIR STATE KAUNAS Arias from: Arias Rachmaninov: Aleko the Tsar & Ludmila,Glinka: A Life for Ruslan Igor Borodin: Prince Boris GodunovMussorgsky: The Demon Rubinstein: Onegin, Iolanthe Eugene Tchaikovsky: Peace and War Prokofiev: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sadko 66:49 Time: Total Russian Arias for Bass ABDRAZAKOV ILDAR POWER PLAYERS ORIGINAL DELOS DE 3456 ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV • POWER PLAYERS DIGITAL POWER PLAYERS Russian Arias for Bass ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV 1. Sergei Rachmaninov: Aleko – “Ves tabor spit” (All the camp is asleep) (6:19) 2. Mikhail Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “Farlaf’s Rondo” (3:34) 3. Glinka: Ruslan & Ludmila – “O pole, pole” (Oh, field, field) (11:47) 4. Alexander Borodin: Prince Igor – “Ne sna ne otdykha” (There’s no sleep, no repose) (7:38) 5. Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov – “Kak vo gorode bylo vo Kazani” (At Kazan, where long ago I fought) (2:11) 6. Anton Rubinstein: The Demon – “Na Vozdushnom Okeane” (In the ocean of the sky) (5:05) 7. Piotr Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Liubvi vsem vozrasty pokorny” (Love has nothing to do with age) (5:37) 8. Tchaikovsky: Iolanthe – “Gospod moi, yesli greshin ya” (Oh Lord, have pity on me!) (4:31) 9. -

Demographic, Economic, Geospatial Data for Municipalities of the Central Federal District in Russia (Excluding the City of Moscow and the Moscow Oblast) in 2010-2016

Population and Economics 3(4): 121–134 DOI 10.3897/popecon.3.e39152 DATA PAPER Demographic, economic, geospatial data for municipalities of the Central Federal District in Russia (excluding the city of Moscow and the Moscow oblast) in 2010-2016 Irina E. Kalabikhina1, Denis N. Mokrensky2, Aleksandr N. Panin3 1 Faculty of Economics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 119991, Russia 2 Independent researcher 3 Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 119991, Russia Received 10 December 2019 ♦ Accepted 28 December 2019 ♦ Published 30 December 2019 Citation: Kalabikhina IE, Mokrensky DN, Panin AN (2019) Demographic, economic, geospatial data for munic- ipalities of the Central Federal District in Russia (excluding the city of Moscow and the Moscow oblast) in 2010- 2016. Population and Economics 3(4): 121–134. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.3.e39152 Keywords Data base, demographic, economic, geospatial data JEL Codes: J1, J3, R23, Y10, Y91 I. Brief description The database contains demographic, economic, geospatial data for 452 municipalities of the 16 administrative units of the Central Federal District (excluding the city of Moscow and the Moscow oblast) for 2010–2016 (Appendix, Table 1; Fig. 1). The sources of data are the municipal-level statistics of Rosstat, Google Maps data and calculated indicators. II. Data resources Data package title: Demographic, economic, geospatial data for municipalities of the Cen- tral Federal District in Russia (excluding the city of Moscow and the Moscow oblast) in 2010–2016. Copyright I.E. Kalabikhina, D.N.Mokrensky, A.N.Panin The article is publicly available and in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC-BY 4.0) can be used without limits, distributed and reproduced on any medium, pro- vided that the authors and the source are indicated. -

Otkhodnichestvo's Impact on Small Towns in Russia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zausaeva, Yana Conference Paper Otkhodnichestvo's impact on small towns in Russia 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Zausaeva, Yana (2014) : Otkhodnichestvo's impact on small towns in Russia, 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124426 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) -

The Great Patriotic War: Figures, Faces and Monuments of Our Victory

0 КОСТРОМСКОЙ ОБЛАСТНОЙ ИНСТИТУТ РАЗВИТИЯ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ Kostroma Land during the Great Patriotic War: figures, faces and monuments of our Victory КОСТРОМА, 2020 1 ББК 81.2Англ-922 УДК 811.111 K 72 Авторский коллектив: И. М. Сидорова, учитель английского языка, Т. В. Смирнова, учитель английского языка, МБОУ Караваевская средняя общеобразовательная школа Костромского муниципального района; Н. В. Пашкевич, методист отдела реализации программ дополнительного образования школьников ОГБОУ ДПО «КОИРО» Рецензенты: Лушина Елена Альбертовна, ректор ОГБОУ ДПО «КОИРО»; Заботкина Ольга Алексеевна, преподаватель Даремского университета (Великобритания), член Союза Журналистов РФ, член Академии высшего образования Великобритании; France Christopher Norman Lee, teacher, Durham; Kjell Eilert Karlsen, Owner and Managing Director of Institute working with Organizational and strategic Management development for Finance and Bank Institutions. Clinical psychologist, Cand. Psychol. University of Bergen, Norway; Connor S. Farris, Teacher of English as a Second Language, the USA; Elena Butler, Alive Mental Health Fair, the USA K 72 Kostroma Land during the Great Patriotic War: figures, faces and monuments of our Victory: Учебное пособие по английскому языку для учащихся 8–11 классов / Авт. И. М. Сидорова, Т. В. Смирнова, Н. В. Пашкевич; ред. Е. А. Лушина, О. А. Заботкина, France Christopher Norman Lee, Kjell Eilert Karlsen, Connor S. Farris, Elena Butler. — Кострома: КОИРО, 2020. — 44 с.: ил. ББК 81.2Англ-922 УДК 811.111 Это пособие посвящено великой дате – 75-летию Победы в Великой Отечественной войне. …Многие страны сейчас пытаются переписать историю, забывая, что именно Советский Союз освободил мир от фашистской чумы, что именно наша страна выстояла и победила в далёком 1945 году. Костромская земля внесла немалый вклад в дело Победы. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

DESIGN CONSTRUCTION |About Company

DESIGN CONSTRUCTION |About Company Successful work amid the First significant contract for global financial crisis; 2001 the General Design and the start of effective reconstruction of the object 2008 - 2010 cooperation with foreign with the total area over customers 15,000 m2; Establishment of the development of order 1992 Research and Production portfolio Company Metallimpress Simultaneous construction which core operation was Foundation of its own 2006 1998 of several large objects design facilities for steel structure production acting as the General Contractor Launch of construction and installation direction 1996 Entry from the regional market to the all-Russian market; taking the repeated orders from the customers; increase in production Active phase of the company 2007 capacity structuring, formation of the Design Active promotion of Team departments: Steel Structures, 2004 «turn-key» construction Detailed Design, Foundation Engineering, Reinforced Concrete Structures, Architectual Solutions, General Plan; Potential growth: the Company is able to carry up the establishment of construction and 2014 to 12 projects simultaneously finishing branch in the construction and production department 1999 2 3 |Company’s Profile |Services The basic model of collaboration with customers is turn-key construction which includes: Industrial facilities: • Automobile plants; GENERAL CONTRACT • Food production; GENERAL DESIGN • Heavy industry plants; TECHNICAL CLIENT • Light industry plants; • Chemical production; Metallimpress is a General Contractor with comprehensive approach to project implementation. • Pharmaceutical production; While performing functions of the General Contractor the Сompany puts emphasis on: • Plants of light and heavy engineering. • Qualified construction management; • Quality of technologies, materials and equipment used under construction; • Compliance with the requirements of environmental protection, occupational health and safety. -

Editorial Satement

92 C O N F E R E N C E R E P O R T S A N D P A N E L S E. E. Lineva: A Conference “E. E. Lineva: the hundredth anniversary of her field recordings,” a conference of both a scholarly and applied nature was held on November 23-25th, 2001 in the old Russian city of Vologda. Evgeniia Eduardovna Lineva (1853-1919) occupies a special place in Russian and American culture. In the 1890s she and her husband, a political émigré, lived in America. There Lineva, a professional singer, organized a Russian folk choir which performed successfully at the Chicago Universal Exhibition held to mark the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America. After her return home Lineva took a more serious interest in Russian folk song, undertaking a number of folklore expeditions to various parts of the country. To Lineva belongs the distinction of being the first to use the phonograph to record folk songs. She used it on her first expedition in 1897 to villages in Nizhnii Novogord, Kostroma, Simbirsk, Tambov and Voronezh provinces. In 1901 the folklorist traveled to the Kirillovo-Belozersk area of Novgorod Province, now part of Vologda Oblast’. One result outcome was the collection Velikorusskie pesni v narodnoi garmonizatsii [Russian songs in their folk harmonization] (pt 1, St. Petersburg, 1904; pt 2, St. Petersburg, 1909), in which the music was deciphered to the highest professional standards. It was the centenary of that expedition of 1901 that prompted the conference. The conference was not the only event commemorating Lineva held in the Vologda area: S. -

Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/98 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Wendy Rosslyn is Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Nottingham, UK. Her research on Russian women includes Anna Bunina (1774-1829) and the Origins of Women’s Poetry in Russia (1997), Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women Writers 1763- 1825 (2000) and Deeds not Words: The Origins of Female Philantropy in the Russian Empire (2007). Alessandra Tosi is a Fellow at Clare Hall, Cambridge. Her publications include Waiting for Pushkin: Russian Fiction in the Reign of Alexander I (1801-1825) (2006), A. M. Belozel’skii-Belozerskii i ego filosofskoe nasledie (with T. V. Artem’eva et al.) and Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825 (2007), edited with Wendy Rosslyn. Women in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Lives and Culture Edited by Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Wendy Rosslyn and Alessandra Tosi Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial