Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Go to Oberhausen! Some Notes on an Online Film Festival Experience

KEIDL MELAMED HEDIGER SOMAINI PANDEMIC MEDIA MEDIA OF FILM OF FILM CONFIGURATIONS CONFIGURATIONS Pandemic Media Configurations of Film Series Editorial Board Nicholas Baer (University of Groningen) Hongwei Thorn Chen (Tulane University) Miriam de Rosa (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice) Anja Dreschke (University of Düsseldorf) Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan (King’s College London) Andrea Gyenge (University of Minnesota) Jihoon Kim (Chung Ang University) Laliv Melamed (Goethe University) Kalani Michell (UCLA) Debashree Mukherjee (Columbia University) Ara Osterweil (McGill University) Petr Szczepanik (Charles University Prague) Pandemic Media: Preliminary Notes Toward an Inventory edited by Philipp Dominik Keidl, Laliv Melamed, Vinzenz Hediger, and Antonio Somaini Bibliographical Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie(GermanNationalBibliography);detailed bibliographic information is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Publishedin2020bymesonpress,Lüneburg,Germany with generous support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft www.meson.press Designconcept:TorstenKöchlin,SilkeKrieg Cover design: Mathias Bär Coverimage:©Antoined’Agata,reprintedwithpermissionfromtheartist Editorial assistance: Fabian Wessels TheprinteditionofthisbookisprintedbyLightningSource, MiltonKeynes,UnitedKingdom ISBN(Print):978-3-95796-008-5 ISBN(PDF): 978-3-95796-009-2 DOI:10.14619/0085 The PDF edition of this publication can -

Karte Der Wahlkreise Für Die Wahl Zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag

Karte der Wahlkreise für die Wahl zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag gemäß Anlage zu § 2 Abs. 2 des Bundeswahlgesetzes, die zuletzt durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 03. Mai 2016 (BGBl. I S. 1062) geändert worden ist Nordfriesland Flensburg 1 Schleswig- Flensburg 2 5 4 Kiel 9 Rendsburg- Plön Rostock 15 Vorpommern- Eckernförde 6 Dithmarschen Rügen Ostholstein Grenze der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Länder Neu- 14 münster Grenze Kreise/Kreisfreie Städte 3 16 Segeberg Steinburg 8 Lübeck Nordwestmecklenburg Rostock Wahlkreisgrenze 11 17 Wahlkreisgrenze 29 Stormarn (auch Kreisgrenze) 7 Vorpommern- Cuxhaven Pinneberg Greifswald Schwerin Wittmund Herzogtum Wilhelms- Lauenburg 26 haven Bremer- 18-23 13 Stade Hamburg Mecklenburgische Saalekreis Kreisname haven 12 24 10 Seenplatte Aurich Halle (Saale) Kreisfreie Stadt Friesland 30 Emden Ludwigslust- Wesermarsch Rotenburg Parchim (Wümme) 36 Uckermark Harburg Lüneburg 72 Wahlkreisnummer Leer Ammerland Osterholz 57 27 Oldenburg (Oldenburg) Prignitz Bremen Gebietsstand der Verwaltungsgrenzen: 29.02.2016 55 35 37 54 Delmen- Lüchow- Ostprignitz- 28 horst 34 Ruppin Heidekreis Dannenberg Oldenburg Uelzen Oberhavel 25 Verden 56 58 Barnim 32 Cloppenburg 44 66 Märkisch- Diepholz Stendal Oderland Vechta 33 Celle Altmarkkreis Emsland Gifhorn Salzwedel Havelland 59 Nienburg 31 75-86 Osnabrück (Weser) Grafschaft 51 Berlin Bentheim 38 Region 43 45 Hannover Potsdam Brandenburg Frankfurt a.d.Havel 63 Wolfsburg (Oder) 134 61 41-42 Oder- Minden- 40 Spree Lübbecke Peine Braun- Börde Jerichower 60 Osnabrück Schaumburg -

RB PD Str. - Nr

Strecke Strecke Freigabe Freigabe RB PD Str. - Nr. Streckenbezeichnung km-Anfang km-Ende km-Anfang km-Ende Nord Kiel 1043 Neumünster, W 23 - Bad Oldesloe, W 22 74,4 + 27 119,8 + 66 74,4 + 27 75,3 + 20 Nord Kiel 1043 Neumünster, W 23 - Bad Oldesloe, W 22 74,4 + 27 119,8 + 66 78,5 + 0 119,8 + 66 Ost Schwerin 1122 Lübeck Hbf, 90W108 - Strasburg (Uckerm), W 48 0,4 + 84 234,1 + 48 58,6 + 55 129,4 + 54 Nord Hamburg 1153 Lüneburg, W 210 - Stelle, W 5 132,9 + 42 157,8 + 75 132,9 + 42 157,8 + 75 Nord Hamburg 1250 Abzw Hamburg Oberhafen, W 4330 - Hamburg Hbf, W 442 352,4 + 56 355,5 + 64 353,5 + 85 355,5 + 64 Nord Bremen 1283 Rotenburg (Wümme), W 12 - Buchholz (Nordh.),W 261 (Mittelgleis) 280,8 + 67 323,4 + 76 280,8 + 67 296,0 + 0 Nord Hamburg 1283 Rotenburg (Wümme), W 12 - Buchholz (Nordh.),W 261 (Mittelgleis) 280,8 + 67 323,4 + 76 296,0 + 0 323,4 + 76 Nord Hamburg 1291 Hamburg-Rothenburgsort, W 123 - Abzw Hamburg Ericus, W 712 282,0 + 11 284,9 + 30 282,0 + 11 284,9 + 30 Nord Bremen 1500 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf - Bremen Hbf, W 110 0,0 + 0 45,1 + 87 0,0 + 0 45,1 + 87 Nord Bremen 1520 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf, W 5 - Leer (Ostfriesl), W 38 0,8 + 42 55,5 + 12 0,8 + 42 55,5 + 12 Nord Bremen 1522 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf - Wilhelmshaven 0,0 + 0 52,3 + 59 0,0 + 0 52,3 + 59 Nord Bremen 1570 Emden Rbf --(Norden)-- - Jever 0,0 + 0 81,0 + 8 0,0 + 0 31,0 + 45 Nord Bremen 1570 Emden Rbf --(Norden)-- - Jever 0,0 + 0 81,0 + 8 60,5 + 80 81,0 + 8 Nord Bremen 1574 Norden, W 35 - Norddeich Mole 30,9 + 41 36,6 + 49 30,9 + 41 36,6 + 49 Nord Osnabrück 1600 Osnabrück Hbf Po, W -

Youtube Videos Cab Rides Strassenbahnen/Tramways in Deutschland/Germany Stand:31.12.2020/Status:31.12.2020 Augsburg

YOUTUBE VIDEOS CAB RIDES STRASSENBAHNEN/TRAMWAYS IN DEUTSCHLAND/GERMANY STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 AUGSBURG: LINE 1:LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-GÖGGINGEN 12.04.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g7eqXnRIey4 GÖGGINGEN-LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 23:04 esbek2 13.01.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1SfRiOz_u4 LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-GÖGGINGEN 31:10 (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) WorldOfTransit 27.05.2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JeDUwVu1rQ GÖGGINGEN-KÖNIGSPLATZ-MORITZPLATZ- DEPOT 22:53 21.09.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbIIg8r0okI AUGSBURG NORD-KÖNIGSPLATZ-GÖGGINGEN 01:03:10 Reiner Benkert 08.01.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyNKAozjSKI LECHHAUSEN NEUER OSTFRIEDHOF-CURTIUSSTRASSE 02:28 RRV LINE 2:AUGSBURG WEST-HAUNSTETTEN NORD 26.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3di8ga1lZE AUGSBURG WEST-HAUNSTETTEN NORD (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 31:33 esbek2 21.06.2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILXRyG9iSoQ OBERHAUSEN-HAUNSTETTEN NORD 32:50 Reiner Benkert 27.12.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__DFdZv7atk MORITZPLATZ-AUGSBURG WEST (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 25:43 PatrickS1968 27.12.2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbt0DIqvwdA AUGSBURG WEST-MORITZPLATZ (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 25:52 PatrickS1968 1 LINE 3:STADTBERGEN-HAUNSTETTEN WEST 13.01.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6fnPJ_W5o5s STADTBERGEN-HAUNSTETTEN WEST (HINTERER FÜHRERSTAND/REAR CAB!) 33:58 WorldOfTransit 08.04.2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1zduTC5_kk HAUNSTETTEN-LECHHAUSEN -

Case Study North Rhine-Westphalia

Contract No. 2008.CE.16.0.AT.020 concerning the ex post evaluation of cohesion policy programmes 2000‐2006 co‐financed by the European Regional Development Fund (Objectives 1 and 2) Work Package 4 “Structural Change and Globalisation” CASE STUDY NORTH RHINE‐WESTPHALIA (DE) Prepared by Christian Hartmann (Joanneum Research) for: European Commission Directorate General Regional Policy Policy Development Evaluation Unit CSIL, Centre for Industrial Studies, Milan, Italy Joanneum Research, Graz, Austria Technopolis Group, Brussels, Belgium In association with Nordregio, the Nordic Centre for Spatial Development, Stockholm, Sweden KITE, Centre for Knowledge, Innovation, Technology and Enterprise, Newcastle, UK Case Study – North Rhine‐Westphalia (DE) Acronyms BERD Business Expenditure on R&D DPMA German Patent and Trade Mark Office ERDF European Regional Development Fund ESF European Social Fund EU European Union GERD Gross Domestic Expenditure on R&D GDP Gross Domestic Product GRP Gross Regional Product GVA Gross Value Added ICT Information and Communication Technology IWR Institute of the Renewable Energy Industry LDS State Office for Statistics and Data Processing NGO Non‐governmental Organisation NPO Non‐profit Organisation NRW North Rhine‐Westphalia NUTS Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics PPS Purchasing Power Standard REN Rational Energy Use and Exploitation of Renewable Resources R&D Research and Development RTDI Research, Technological Development and Innovation SME Small and Medium Enterprise SPD Single Programming Document -

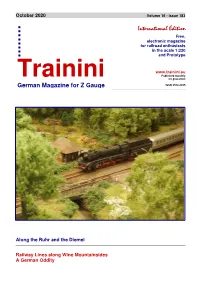

Trainini Model Railroad Magazine

October 2020 Volume 16 • Issue 183 International Edition Free, electronic magazine for railroad enthusiasts in the scale 1:220 and Prototype www.trainini.eu Published monthly Trainini no guarantee German Magazine for Z G auge ISSN 2512-8035 Along the Ruhr and the Diemel Railway Lines along Wine Mountainsides A German Oddity Trainini ® International Edition German Magazine for Z Gauge Introduction Dear Readers, If I were to find a headline for this issue that could summarise (almost) all the articles, it would probably have to read as follows: “Travels through German lands”. That sounds almost a bit poetic, which is not even undesirable: Our articles from the design section invite you to dream or help you to make others dream. Holger Späing Editor-in-chief With his Rhosel layout Jürgen Wagner has created a new work in which the landscape is clearly in the foreground. His work was based on the most beautiful impressions he took from the wine-growing regions along the Rhein and Mosel (Rhine and Moselle). At home he modelled them. We like the result so much that we do not want to withhold it from our readers! We are happy and proud at the same time to be the first magazine to report on it. Thus, we are today, after a short break in the last issue, also continuing our annual main topic. We also had to realize that the occurrence of infections has queered our pitch. As a result, we have not been able to take pictures of some of the originally planned layouts to this day, and many topics have shifted and are now threatening to conglomerate towards the end of the year. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001

ICPSR 2683 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001 Virginia Sapiro W. Philips Shively Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 4th ICPSR Version February 2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu Terms of Use Bibliographic Citation: Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Secretariat. COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS, 1996-2001 [Computer file]. 4th ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer], 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2004. Request for Information on To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of Use of ICPSR Resources: archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Visit the ICPSR Web site for more information on submitting citations. Data Disclaimer: The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Responsible Use In preparing data for public release, ICPSR performs a number of Statement: procedures to ensure that the identity of research subjects cannot be disclosed. Any intentional identification or disclosure of a person or establishment violates the assurances of confidentiality given to the providers of the information. -

Bahnstrecke Duisburg-Ruhrort–Mönchengladbach

Bahnstrecke Duisburg-Ruhrort–Mönchengladbach Die Bahnstrecke Duisburg-Ruhrort– Noch bevor sie ihre Strecke vollendet hatte, wurde die Mönchengladbach ist eine historisch bedeutsame, RCG am 1. April 1850 zusammen mit der AND in heute aber zum Teil stillgelegte Eisenbahnstrecke in staatliche Verwaltung überführt und der „Königlichen Deutschland. Die Strecke wurde von der Ruhrort- Direktion der Aachen-Düsseldorf-Ruhrorter Eisenbahn- Crefeld-Kreis Gladbacher Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft Gesellschaft“ unterstellt. Diese wurde dann am 1. Januar (RCG) erbaut, die 1847 eine entsprechende Konzession 1866 von der (ebenfalls staatlich verwalteten) Bergisch- erhalten hatte. Märkischen Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (BME) übernom- Der größere Teil der Strecke bildet heute zusammen men. mit dem westlichen Teil der Ruhrgebietsstrecke der Die BME baute daraufhin ausgehend von ihrem Rheinischen Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (RhE) als Bahn- Bahnhof in Mülheim-Styrum eine Stichstrecke ihrer strecke Duisburg–Mönchengladbach eine der wich- 1862 eröffneten Bahnstrecke Witten/Dortmund– tigsten Eisenbahnverbindungen des linken Niederrheins Oberhausen/Duisburg nach Duisburg-Ruhrort, und von Duisburg Hbf nach Mönchengladbach Hbf. führte eine durchgehende Kilometrierung vom ehema- ligen Bahnhof Aachen RhE/Marschierthor (Kilometer 0,0) nach Dortmund Hbf (Kilometer 164,3) ein. 1 Geschichte 1.2 Teilstilllegung 1.1 Anfangszeit Nachdem die RhE ihre ursprüngliche Trajektanstalt Die Bahnstrecke Ruhrort–Crefeld−Kreis Gladbach durch die Duisburg-Hochfelder Eisenbahnbrücke ersetzt sollte ein Verkehrsweg sein, um die im Ruhrgebiet geför- hatte, lief diese dem Trajekt Ruhrort–Homberg schnell derte Kohle zu den Verbrauchern am linken Niederrhein den Rang ab. Infolgedessen verlor auch der Streckenab- bringen zu können. Die RCG schloss daher einen Vertrag schnitt von Duisburg-Homberg nach Hohenbudberg zu- mit der Köln-Mindener Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (CME), nehmend an Bedeutung. -

Liste Der Jungmeister 2018

Jungmeister*innen 2018 Handwerk Name Vorname Ort Landkreis Bäcker Beha Andreas Titisee-Neustadt Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Bäcker Schütz Michael St. Peter Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Brunn Tino Heuweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Eckerle Markus Oberried Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Felice Fabio Gundelfingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Frey Rainer Badenweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Graf Daniel Müllheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Helm Kevin Buggingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Kathan Michael Artur March-Holzhausen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Kraus Witali Merdingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Ruh Marius Pfaffenweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schmidt Adrian Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schmidt Manuel Breisach Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schwär Hannes Titisee-Neustadt Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Wiegand Oleg Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Deger Christian Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Knörr Lukas Ehrenstetten Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Wetzel Marvin Müllheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Andresen Juliane Bad Krozingen-Biengen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Bergsma Julia Patricia Neuenburg am Rhein Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Jaekel Lisa Lenzkirch Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Philipp Selina Heitersheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Holzbildhauer Acar Joana Ilayda Merzhausen -

Urban Change Cultural Makers and Spaces in the Ruhr Region

PART 2 URBAN CHANGE CULTURAL MAKERS AND SPACES IN THE RUHR REGION 3 | CONTENT URBAN CHANGE CULTURAL MAKERS AND SPACES IN THE RUHR REGION CONTENT 5 | PREFACE 6 | INTRODUCTION 9 | CULTURAL MAKERS IN THE RUHR REGION 38 | CREATIVE.QUARTERS Ruhr – THE PROGRAMME 39 | CULTURAL PLACEMAKING IN THE RUHR REGION 72 | IMPRINT 4 | PREFACE 5 | PREFACE PREFACE Dear Sir or Madam, Dear readers of this brochure, Individuals and institutions from Cultural and Creative Sectors are driving urban, Much has happened since the project started in 2012: The Creative.Quarters cultural and economic change – in the Ruhr region as well as in Europe. This is Ruhr are well on their way to become a strong regional cultural, urban and eco- proven not only by the investment of 6 billion Euros from the European Regional nomic brand. Additionally, the programme is gaining more and more attention on Development Fund (ERDF) that went into culture projects between 2007 and a European level. The Creative.Quarters Ruhr have become a model for a new, 2013. The Ruhr region, too, exhibits experience and visible proof of structural culturally carried and integrative urban development in Europe. In 2015, one of change brought about through culture and creativity. the projects supported by the Creative.Quarters Ruhr was even invited to make a presentation at the European Parliament in Brussels. The second volume of this brochure depicts the Creative.Quarters Ruhr as a building block within the overall strategy for cultural and economic change in the Therefore, this second volume of the brochure “Urban Change – Cultural makers Ruhr region as deployed by the european centre for creative economy (ecce). -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating' adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding o f the dissertation. -

Shrinking German Cities -The Cases of Halle and Gelsenkirchen

Master Thesis Shrinking German cities -The cases of Halle and Gelsenkirchen- Author: Nora Kaminski Supervisor: Jan-Evert Nilsson Tutor: Alina Lidén Submitted to Blekinge Tekniska Högskola for the Master of European Spatial Planning and Regional Development on the 13/04/2012 Abstract The thesis researches the reasons of shrinking cities, especially the impact of deindustrialisation, in Germany using the example of Halle and Gelsenkirchen. Additionally, the policy response towards this phenomenon in terms of urban consolidation in the cities is posed. For doing that, the economic history of the towns is investigated and simultaneously the development of population and of unemployment is researched, as they are closely connected to the economy. With an analysis of the proportion of employees in the different economic sectors in the course of time the structural change becomes more obvious. A shifting has taken place: both cities engage currently more people in the tertiary sector and less people in the secondary sector as twenty years ago. Concluding all indicators it can be said that a deindustrialisation took place. However, also other influences on shrinking, as for example migration, are described and their impact on both cities is explained. With investigating the consolidation areas of the programme Stadtumbau Ost and Stadtumbau West in Halle and Gelsenkirchen the possible course of action by the policy is presented and those areas in Halle and Gelsenkirchen are identified, which have the biggest population decline and the highest vacancy rates. Critique about the Stadtumbau programme is given at the end of the research. The result of the analysis is that deindustrialisation can explain big parts of the shrinking process in both cities.