Protection of Norwegian Orchids – a Review of Achievements and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Orchids Orchids Are the Lady’S Slippers, So Named and Lake Huron

By Tom Shields Photos by Kevin Tipson and Henry Glowka unless otherwise indicated jewels of the Biosphere res The Niagara Escarpment is justly famous as a uNESCo World Biosphere Reserve, one of Canada’s first. In Southern ontario, its tower - ing dolostone cliffs, formed in ancient seas more than 420 million years ago, rise dramatically along a jagged line that stretches 725 kilo - metres from the Niagara River to the tip of Tobermory. From these heights the Escarpment tilts down gently to the west. Rainfall and ground water seep gradually through its porous rocks, creating swamps, fens, bogs, marshes, valleys, caves, and microcli - mates across the meandering band that follows its length. 28 BRuCE TRAIL MAGAzINE SPRING 201 4 erve d n a l c A e c n e r u a L : o t o h P WWW.BRuCETRAIL.oRG BRuCE TRAIL MAGAzINE 29 Nowhere are these features more promi - LADY’S SLIPPERS (CYPRIPEDIUM) nent than in the Bruce Peninsula, Easiest to find and most familiar of our enrobed on either side by Georgian Bay distinguishing orchids orchids are the lady’s slippers, so named and Lake Huron. Here, jewel-like mem - All orchids have a highly modified, due to the fancied resemblance of their bers of one of the Escarpment’s other pouched lip to an old-fashioned slipper lavish petal called the lip. usually it claims to fame grow with an abundance or moccasin. The flowers are often large is held at the bottom of the flower, and diversity thought unequalled else - and showy. Four of the nine species but sometimes at the top. -

The Genomic Impact of Mycoheterotrophy in Orchids

fpls-12-632033 June 8, 2021 Time: 12:45 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 09 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.632033 The Genomic Impact of Mycoheterotrophy in Orchids Marcin J ˛akalski1, Julita Minasiewicz1, José Caius2,3, Michał May1, Marc-André Selosse1,4† and Etienne Delannoy2,3*† 1 Department of Plant Taxonomy and Nature Conservation, Faculty of Biology, University of Gdansk,´ Gdansk,´ Poland, 2 Institute of Plant Sciences Paris-Saclay, Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, INRAE, Univ Evry, Orsay, France, 3 Université de Paris, CNRS, INRAE, Institute of Plant Sciences Paris-Saclay, Orsay, France, 4 Sorbonne Université, CNRS, EPHE, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité, Paris, France Mycoheterotrophic plants have lost the ability to photosynthesize and obtain essential mineral and organic nutrients from associated soil fungi. Despite involving radical changes in life history traits and ecological requirements, the transition from autotrophy Edited by: Susann Wicke, to mycoheterotrophy has occurred independently in many major lineages of land Humboldt University of Berlin, plants, most frequently in Orchidaceae. Yet the molecular mechanisms underlying this Germany shift are still poorly understood. A comparison of the transcriptomes of Epipogium Reviewed by: Maria D. Logacheva, aphyllum and Neottia nidus-avis, two completely mycoheterotrophic orchids, to other Skolkovo Institute of Science autotrophic and mycoheterotrophic orchids showed the unexpected retention of several and Technology, Russia genes associated with photosynthetic activities. In addition to these selected retentions, Sean W. Graham, University of British Columbia, the analysis of their expression profiles showed that many orthologs had inverted Canada underground/aboveground expression ratios compared to autotrophic species. Fatty Craig Barrett, West Virginia University, United States acid and amino acid biosynthesis as well as primary cell wall metabolism were among *Correspondence: the pathways most impacted by this expression reprogramming. -

Review Article Conservation Status of the Family Orchidaceae in Spain Based on European, National, and Regional Catalogues of Protected Species

Hind ile Scientific Volume 2018, Article ID 7958689, 18 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7958689 Hindawi Review Article Conservation Status of the Family Orchidaceae in Spain Based on European, National, and Regional Catalogues of Protected Species Daniel de la Torre Llorente© Biotechnology-Plant Biology Department, Higher Technical School of Agronomic, Food and Biosystems Engineering, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, 28140 Madrid, Spain Correspondence should be addressed to Daniel de la Torre Llorente; [email protected] Received 22 June 2017; Accepted 28 December 2017; Published 30 January 2018 Academic Editor: Antonio Amorim Copyright © 2018 Daniel de la Torre Llorente. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Tis report reviews the European, National, and Regional catalogues of protected species, focusing specifcally on the Orchidaceae family to determine which species seem to be well-protected and where they are protected. Moreover, this examination highlights which species appear to be underprotected and therefore need to be included in some catalogues of protection or be catalogued under some category of protection. Te national and regional catalogues that should be implemented are shown, as well as what species should be included within them. Tis report should be a helpful guideline for environmental policies about orchids conservation in Spain, at least at the regional and national level. Around 76% of the Spanish orchid fora are listed with any fgure of protection or included in any red list, either nationally (about 12-17%) or regionally (72%). -

Watsonia 14 (1982), 79-100

Walsonia , 14, 79-100 (\982) 79 Book Reviews Flowers of Greece and the Balkans. A field guide. Oleg Polunin. Pp. xv+592 including 62 pages of line drawings and 21 maps, with 80 colour plates. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1980. Price £40.00 (ISBN 0-19- 217-6269). This latest of Oleg Polunin's Field guides to the European flora presents a concise, but by no means superficial, picture of the flowering plants and conifers of the Balkan peninsula. The area that is covers takes in the whole of Greece (including the East Aegean Islands, excluded from Flora Europaea), Turkey-in-Europe, Albania, Bulgaria, Jugoslavia as far north as the River Sava, and the small portion of Romania that lies south and east of the River Danube. The author has condensed his account of the rich and varied flora of the region, together with the associated mass of published material, into a form that is attractive, comprehensible and useful to the amateur botanist. A book of this type has been badly needed, as the available floristic texts on the Balkans tend to be over 50 years old, scarce, extremely expensive and written in a foreign language, often Latin. However, the most significant attribute of this book is not that it gives access to diffuse and obscure information, but that it provides a radical alternative to popular botanical accounts of Greece which emphasize the lowland spring flora, notably the orchids and other petaloid monocots. Based on the author's many years of botanical experience and extensive travel in the region, Flowers of Greece and the Balkans demonstrates the wide range of flora and vegetation that the amateur botanist can expect to see in the Balkan peninsula. -

The Analysis of the Flora of the Po@Ega Valley and the Surrounding Mountains

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NAT. CROAT. VOL. 7 No 3 227¿274 ZAGREB September 30, 1998 ISSN 1330¿0520 UDK 581.93(497.5/1–18) THE ANALYSIS OF THE FLORA OF THE PO@EGA VALLEY AND THE SURROUNDING MOUNTAINS MIRKO TOMA[EVI] Dr. Vlatka Ma~eka 9, 34000 Po`ega, Croatia Toma{evi} M.: The analysis of the flora of the Po`ega Valley and the surrounding moun- tains, Nat. Croat., Vol. 7, No. 3., 227¿274, 1998, Zagreb Researching the vascular flora of the Po`ega Valley and the surrounding mountains, alto- gether 1467 plant taxa were recorded. An analysis was made of which floral elements particular plant taxa belonged to, as well as an analysis of the life forms. In the vegetation cover of this area plants of the Eurasian floral element as well as European plants represent the major propor- tion. This shows that in the phytogeographical aspect this area belongs to the Eurosiberian- Northamerican region. According to life forms, vascular plants are distributed in the following numbers: H=650, T=355, G=148, P=209, Ch=70, Hy=33. Key words: analysis of flora, floral elements, life forms, the Po`ega Valley, Croatia Toma{evi} M.: Analiza flore Po`e{ke kotline i okolnoga gorja, Nat. Croat., Vol. 7, No. 3., 227¿274, 1998, Zagreb Istra`ivanjem vaskularne flore Po`e{ke kotline i okolnoga gorja ukupno je zabilje`eno i utvr|eno 1467 biljnih svojti. Izvr{ena je analiza pripadnosti pojedinih biljnih svojti odre|enim flornim elementima, te analiza `ivotnih oblika. -

Phylogenetics of Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae)

Annals of Botany 110: 71–90, 2012 doi:10.1093/aob/mcs083, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Phylogenetics of tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) based on combined DNA matrices: inferences regarding timing of diversification and evolution of pollination syndromes Luis A. Inda1,*, Manuel Pimentel2 and Mark W. Chase3 1Escuela Polite´cnica Superior de Huesca, Universidad de Zaragoza, carretera de Cuarte sn. 22071 Huesca, Spain, 2Facultade de Ciencias, Universidade da Corun˜a, Campus da Zapateira sn. 15071 A Corun˜a, Spain and 3Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3DS, UK * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 3 November 2011 Returned for revision: 9 December 2011 Accepted: 1 March 2012 Published electronically: 25 April 2012 † Background and aims Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) comprises around 62 mostly terrestrial genera, which are well represented in the Northern Temperate Zone and less frequently in tropical areas of both the Old and New Worlds. Phylogenetic relationships within this tribe have been studied previously using only nuclear ribosomal DNA (nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer, nrITS). However, different parts of the phylogenetic tree in these analyses were weakly supported, and integrating information from different plant genomes is clearly necessary in orchids, where reticulate evolution events are putatively common. The aims of this study were to: (1) obtain a well-supported and dated phylogenetic hypothesis for tribe Orchideae, (ii) assess appropriateness of recent nomenclatural changes in this tribe in the last decade, (3) detect possible examples of reticulate evolution and (4) analyse in a temporal context evolutionary trends for subtribe Orchidinae with special emphasis on pollination systems. -

Orchids of Lakeland

a field guide to OrchidsLakeland Provincial Park, Provincial Recreation Area and surrounding region Written by: Patsy Cotterill Illustrated by: John Maywood Pub No: I/681 ISBN: 0-7785-0020-9 Printed 1998 Sepal Sepal Petal Petal Seed Sepal Lip (labellum) Ovary Finding an elusive (capsule) orchid nestled away in Sepal the boreal forest is a Scape thrilling experience for amateur and Petal experienced naturalists alike. This type Petal of recreation has become a passion for Column some and, for many others, a wonder- ful way to explore nature and learn Ovary Sepal (capsule) more about the living world around us. Sepal But, we also need to be careful when Lip (labellum) looking at these delicate plants. Be mindful of their fragile nature... keep Spur only memories and take only photo- graphs so that others, too, can enjoy. Corm OrchidsMany people are surprisedin Alberta to learn that orchids grow naturally in Alberta. Orchids are typically associated with tropical rain forests (where indeed, many do grow) or flower-shop purchases for special occasions, exotic, expensive and highly ornamental. Wild orchids in fact are found world-wide (except in Antarctica). They constitute Roots Tuber the second largest family of flowering plants (the Orchidaceae) after the Aster family, with upwards of 15,000 species. In Alberta, there are 26 native species. Like all Roots orchids from north temperate regions, these are terrestrial. They grow in the ground, in contrast to the majority of rain forest species which are epiphytes, that is, they grow attached to trees for support but do not derive nourishment from them. -

151-170 Peruzzi

INFORMATORE BOTANICO ITALIANO, 42 (1) 151-170, 2010 151 Checklist dei generi e delle famiglie della flora vascolare italiana L. PERUZZI ABSTRACT - Checklist of genera and families of Italian vascular flora -A checklist of the genera and families of vascular plants occurring in Italy is presented. The families were grouped according to the main six taxonomic groups (e.g. sub- classes: Lycopodiidae, Ophioglossidae, Equisetidae, Polypodiidae, Pinidae, Magnoliidae) and put in systematic order accord- ing to the most recent criteria (e.g. APG system etc.). The genera within each family are arranged in alphabetic order and delimited through recent literature survey. 55 orders (51 native and 4 exotic) and 173 families were recorded (158 + 24), for a total of 1297 genera (1060 + 237). Families with the highest number of genera were Poaceae (126 + 23) and Asteraceae (125 + 23), followed by Apiaceae (85 + 5), Brassicaceae (64 + 5), Fabaceae (45 + 19) etc. A single genus resulted narrow endemic of Italy (Sicily): the monotypic Petagnaea (Apiaceae). Three more genera are instead endemic to Sardinia and Corse: Morisia (Brassicaceae), Castroviejoa and Nananthea (Asteraceae). Key words: classification, families, flora, genera, Italy Ricevuto il 16 Novembre 2009 Accettato il 5 Marzo 2010 INTRODUZIONE Successivamente alla “Flora d’Italia” di PIGNATTI Flora Europaea (BAGELLA, URBANI, 2006; (1982), i progressi negli studi biosistematici e filoge- BOCCHIERI, IIRITI, 2006; LASTRUCCI, RAFFAELLI, netici hanno prodotto una enorme mole di cono- 2006; ROMANO et al., 2006; MAIORCA et al., 2007; scenze circa le piante vascolari. Nella recente CORAZZI, 2008) a tentantivi di aggiormanento Checklist della flora vascolare italiana e sua integra- “misti”, basati sul totale o parziale accoglimento di zione (CONTI et al., 2005, 2007a) non vengono prese classificazioni successive, spesso non ulteriormente in considerazione le famiglie di appartenenza delle specificate (es. -

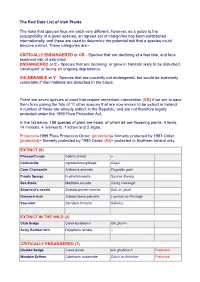

The Red Data List of Irish Plants

The Red Data List of Irish Plants The risks that species face are each very different, however, as a guide to the susceptibility of a given species, an agreed set of categories has been established internationally, and these are used to determine the potential risk that a species could become extinct. These categories are:- CRITICALLY ENDANGERED or CR - Species that are declining at a fast rate, and face imminent risk of extinction. ENDANGERED or E - Species that are declining, or grow in habitats likely to be disturbed, 'developed' or facing an ongoing degradation. VULNERABLE or V - Species that are currently not endangered, but would be extremely vulnerable if their habitats are disturbed in the future. There are seven species of plant that require immediate intervention (CR) if we are to save them from joining the fate of 11 other species that are now known to be extinct in Ireland. A number of these are already extinct in the Republic, and are not therefore legally protected under the 1999 Flora Protection Act. In the list below, 188 species of plant are listed, of which 64 are flowering plants, 4 ferns, 14 mosses, 4 liverworts, 1 lichen and 2 algae. Protected=1999 Flora Protection Order; (protected)= formerly protected by 1987 Order; {protected}= formerly protected by 1980 Order; (NI)= protected in Northern Ireland only. EXTINCT (9) Pheasant's-eye Adonis annua -- Corncockle Agrostemma githago Cogal Corn Chamomile Anthemis arvensis Fíogadán goirt Purple Spurge Euphorbia peplis Spuirse dhearg Sea Stock Matthiola sinuata Tonóg chladaigh -

“Dynamic Speciation Processes in the Mediterranean Orchid Genus Ophrys L

“DYNAMIC SPECIATION PROCESSES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ORCHID GENUS OPHRYS L. (ORCHIDACEAE)” Tesi di Dottorato in Biologia Avanzata, XXIV ciclo (Indirizzo Sistematica Molecolare) Universitá degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Facoltá di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche e Naturali Dipartimento di Biologia Strutturale e Funzionale 1st supervisor: Prof. Salvatore Cozzolino 2nd supervisor: Prof. Serena Aceto PhD student: Dott. Hendrik Breitkopf 1 Cover picture: Pseudo-copulation of a Colletes cunicularius male on a flower of Ophrys exaltata ssp. archipelagi (Marina di Lesina, Italy. H. Breitkopf, 2011). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1: MULTI-LOCUS NUCLEAR GENE PHYLOGENY OF THE SEXUALLY DECEPTIVE ORCHID GENUS OPHRYS L. (ORCHIDACEAE) CHAPTER 2: ANALYSIS OF VARIATION AND SPECIATION IN THE OPHRYS SPHEGODES SPECIES COMPLEX CHAPTER 3: FLORAL ISOLATION IS THE MAIN REPRODUCTIVE BARRIER AMONG CLOSELY RELATED SEXUALLY DECEPTIVE ORCHIDS CHAPTER 4: SPECIATION BY DISTURBANCE: A POPULATION STUDY OF CENTRAL ITALIAN OPHRYS SPHEGODES LINEAGES CONTRIBUTION OF CO-AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 GENERAL INTRODUCTION ORCHIDS With more than 22.000 accepted species in 880 genera (Pridgeon et al. 1999), the family of the Orchidaceae is the largest family of angiosperm plants. Recently discovered fossils document their existence for at least 15 Ma. The last common ancestor of all orchids has been estimated to exist about 80 Ma ago (Ramirez et al. 2007, Gustafsson et al. 2010). Orchids are cosmopolitan, distributed on all continents and a great variety of habitats, ranging from deserts and swamps to arctic regions. Two large groups can be distinguished: Epiphytic and epilithic orchids attach themselves with aerial roots to trees or stones, mostly halfway between the ground and the upper canopy where they absorb water through the velamen of their roots. -

Circumscribing Genera in the European Orchid Flora: a Subjective

Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orchid. Beiheft 8; 2012: 94 - 126 Circumscribing genera in the European orchid lora: a subjective critique of recent contributions Richard M. BATEMAN Keywords: Anacamptis, Androrchis, classiication, evolutionary tree, genus circumscription, monophyly, orchid, Orchidinae, Orchis, phylogeny, taxonomy. Zusammenfassung/Summary: BATEMAN , R. M. (2012): Circumscribing genera in the European orchid lora: a subjective critique of recent contributions. – Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orch. Beiheft 8; 2012: 94 - 126. Die Abgrenzung von Gattungen oder anderen höheren Taxa erfolgt nach modernen Ansätzen weitestgehend auf der Rekonstruktion der Stammesgeschichte (Stamm- baum-Theorie), mit Hilfe von großen Daten-Matrizen. Wenngleich aufgrund des Fortschritts in der DNS-Sequenzierungstechnik immer mehr Merkmale in der DNS identiiziert werden, ist es mindestens genauso wichtig, die Anzahl der analysierten Planzen zu erhöhen, um genaue Zuordnungen zu erschließen. Die größere Vielfalt mathematischer Methoden zur Erstellung von Stammbäumen führt nicht gleichzeitig zu verbesserten Methoden zur Beurteilung der Stabilität der Zweige innerhalb der Stammbäume. Ein weiterer kontraproduktiver Trend ist die wachsende Tendenz, diverse Datengruppen mit einzelnen Matrizen zu verquicken, die besser einzeln analysiert würden, um festzustellen, ob sie ähnliche Schlussfolgerungen bezüglich der Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse liefern. Ein Stammbaum zur Abgrenzung höherer Taxa muss nicht so robust sein, wie ein Stammbaum, aus dem man Details des Evo- lutionsmusters