A Higher Education Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Annual Report

RMIT UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY RMIT » ANNUAL REPORT 2010 REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT 2010 www.rmit.edu.au OBJECTS OF RMIT UNIVERSITY GLOSSARY Extract from the RMIT Act 2010 AASB Australian Accounting Standards Board The objects of the University include: AFL Australian Football League (a) to provide and maintain a teaching and learning environment ALTC Australian Learning and Teaching Council of excellent quality offering higher education at an international ARC Australian Research Council standard; ATN Australian Technology Network of Universities (b) to provide vocational education and training, further education ATSI Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other forms of education determined by the University to CELTA Certificate in English Language eachingT to Adults support and complement the provision of higher education by the University; CEQ Course Experience Questionnaire CRC Cooperative Research Centre (c) to undertake scholarship, pure and applied research, invention, innovation, education and consultancy of international standing DEEWR Commonwealth Department of Education, Employment and to apply those matters to the advancement of knowledge and Workplace Relations and to the benefit of the well-being of the Victorian, Australian DSC RMIT College of Design and Social Context and international communities; DVC Deputy Vice-Chancellor (d) to equip graduates of the University to excel in their chosen EFT Equivalent full-time careers and to contribute to the life of the community; EFTSL Equivalent full-time study load (e) to serve -

By Design Annual Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 REPORT ANNUAL BY DESIGN BY URBAN RMIT UNIVERSITY » ANNUAL REPORT 2011 OBJECTS OF RMIT UNIVERSITY GLOSSARY Extract from the RMIT Act 2010 AASB Australian Accounting Standards Board The objects of the University include: AIA Advertising Institute of Australasia (a) to provide and maintain a teaching and learning environment ALTC Australian Learning and Teaching Council of excellent quality offering higher education at an international APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation standard; AQTF Australian Quality Training Framework (b) to provide vocational education and training, further education ARC Australian Research Council and other forms of education determined by the University to ATAR Australian Tertiary Admission Rank support and complement the provision of higher education by the University; CELTA Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults CEQ Course Experience Questionnaire (c) to undertake scholarship, pure and applied research, invention, innovation, education and consultancy of international standing CRC Cooperative Research Centre and to apply those matters to the advancement of knowledge CRICOS Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for and to the benefit of the well-being of the Victorian, Australian Overseas Students and international communities; DDA Disability Discrimination Act (d) to equip graduates of the University to excel in their chosen DEEWR Commonwealth Department of Education, Employment careers and to contribute to the life of the community; and Workplace Relations (e) to serve -

RMIT University Student Union Third Quarter Report

RMIT University Student Union Third Quarter Report Reporting Period: 1 July – 30 September 2017 RMIT UNIVERSITY STUDENT UNION President’s Report What a massive quarter for the RMIT University Student Union! This period is always an exciting one for RUSU, as it means it’s election time - a fantastic opportunity for students to express what kind of leadership and direction they want from their student union. The election was hard-fought, as usual, but fair, as always. This year saw a significant increase in the number of votes posted from last year, a sure sign that students are actively aware of RUSU but also that students across RMIT’s campuses are being heard. We look forward to welcoming a new group of student advocates later in the year, and we can’t wait to see what kind of energy they bring. Speaking of RMIT’s various campuses, we have seen great progress this quarter in our engagement plan for Point Cook. We are now proudly running a free regular lunch event at Point Cook, something students attending this campus have missed out on for a long time! Bundoora has seen a huge amount of events and activities this quarter, as has Brunswick. We’re really pleased with the way RUSU has engaged with these outer campuses, and it’s a great credit to the staff and student representatives who work with and represent these particular student communities. On the City campus, RUSU was proud to open our new activity space in the NAS precinct. Located just beneath our new front office, the space will give our clubs and departments the room to hold large-scale events and training sessions that would not be possible in our other spaces. -

Rmit Village 94 89

City campus buildings not on this map: CITY CAMPUS » Building 154 (Royal Dental Hospital, 720 Swanston Street, Carlton) A A Queensberry Street LEGEND 55 the Hub B B 56 Library C Wheelchair access 76 C 43 55 Building number 74 57 D 69 D Hall Landmark 71 S Security E 42 95 45 E P Parking 70 Earl Street F F 78 66 Car RMIT VILLAGE 94 89 93 L digan Str y 73 Ro G ygon Str G a 75 Orr Str 96 50 l Pre Site under 97 53 Flemington construction 52 eet eet H 91 98 eet H R 51 d Grattan St RMIT Village Eliz Ly gon St gon Victoria Street Blackwood St a I I beth St City Baths Therry Street Victoria St J 105 J RMIT University 9 13 Franklin St Russell St eet 11 Peel St « S Swan K Franklin Str tr 14 K ams: obe St s Tr ton St La Stewart Str 1 • 3 • 12 49 39 7 L L 5 • Old Melbourne Gaol 85 Site under Casey Plaza Theatre 6 10 construction • 8 M 15 RMIT BOURKE ST eet M • 5 Alumni 88 16 • 64 • d 81 Kaleide Theatre Courtyar Bourke Street P 8 108 19 Swanston Street N t 3 Russell Str N ee 72 6 Bowen Str Beckett Str » A’ 37 O 28 O 21 Swanston Str eet 38 4 86 eet 16 20 P P t 1 » ree 2 • 30 • 24 Little Collins Street obe St Storey Hall circle Little La Tr « trams: 36 24 Ormond statue 101 Q eet Q 22 Elizabeth Stre RMIT Bookshop e R R RMIT Capitol Theatr eet to 239 Bourke Street, Bldg 108 113 obe Str La Tr Victoria State Library Services. -

Second Quarter Report

RMIT University RMIT Student Union Funding Agreement 2011 Second Quarter Report Reporting Period 01/04/2011 - 30/06/2011 www.su.rmit.edu.au www.facebook.com/RUSUpage www.twitter.com/RMITSU www.youtube/RUSUonline www.su.rmit.edu.au . www.facebook.com/RUSUpage . www.twitter.com/RMITSU . www.youtube/RUSUonline 1 President’s Report It’s been a big quarter. In a recent visit to the Ho Chi Minh campus of RMIT Vietnam I experienced first hand both what a ‘global experience’ could be, and what it’s like to be an international student in a foreign country. The campus itself is fantastic and it’s heartening to know it will soon be forming its own student association, a development we’ll be watching with keen interest and excitement. RMIT has also released its Strategic Plan to 2015, and one of the key aspects of this document is its prioritisation of the Student Experience. We look forward to playing a constructive role in helping the University achieve its objectives, and also the chance to point out where it can improve and progress. It’s encouraging to see RMIT prioritize this is as an objective. It’s been a big quarter for us in terms of events and activities, we’ve piloted a new ‘Drinks with Friends’ event on Thursday afternoons at RMIT’s new on campus café, Pearson and Murphy’s, which has been a big success in bringing students together and giving them time to socialize and unwind. Our weekly BBQs have been growing bigger each week, and now engage many RMIT volunteers and students who want a quick feed or a drink. -

Second QUARTER Report Reporting Period 01/04/2013–30/06/2013

SECOND QUARTER REPORT REPORTING PERIOD 01/04/2013–30/06/2013 ░ su.rmit.edu.au ░ facebook.com/RUSUpage ░ twitter.com/RMITSU ░ youtube.com/RUSUonline ░ President’s Report This quarter’s report showcases the results of many months of planning and preparation. With the academic year of 2013 in full swing, RUSU’s many depart- ments and collectives have come alive all across the campuses. James Michelmore Re-Orientation Week saw students at every campus engage with our student clubs and learn of opportunities outside the classrooms. Thousands of students got involved and we sent off the week with one of our ever-popular evening parties, attended by hundreds of RMIT students. Our student collectives continue to flourish, with the Environ- ment Collective coming in to its stride this quarter - over 150 interested students have signed up so far. Regular meetings of students have been occurring, including trips to our ‘pop up patch’ at Federation Square and planning for future projects and events. In addition, this quarter saw the Environment Department launch its healthy-eating cookbook, ‘Beyond Mi Goreng’, and its popularity has sparked calls for a second edition. Watch this space. This quarter has seen our Student Rights Department focus upon the University’s proposed ‘Fitness For Study’ policies. We continue to express our concerns to the University that issues of mental health and student conduct need to be dealt with in a holistic and supportive manner, rather than with the proposed invasive, punitive measures. After much consulta- tion, the University is now re-drafting these policies and we will continue to work together over the coming months to develop the best possible outcome for students. -

Host Liability

HOST LIABILITY Named Insured: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology trading as RMIT University, its subsidiaries and its controlled entities; including RMIT Foundation; RMIT Link; RMIT Training Pty Ltd and RMIT Training Pty Ltd operating as RMIT Training Middle East; Spatial Vision Innovations Pty Ltd; RMIT Vietnam Holdings Pty Ltd; RMIT University Vietnam Limited Liability Company trading as RMIT International University Vietnam; Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Spain, S.L. trading as RMIT Europe; and RMIT Student Union trading as RMIT University Student Union Contractors and coaches of RMIT Link Description of Business: Principally education; training; teaching; research; testing and development; experimentation; consulting and other professional services; property owners and occupiers; hall and facility hire; sporting activities, adventure activities and sporting amenities; cultural activities; sleeping accommodation; student, staff and alumni supporting services; contracted teaching, coaching, mentoring and/or instruction services, dance training, creative arts training and workshop facilitation services, performing arts training, performing arts sets and sound design; and any other occupations incidental thereto. Insured ABN / ITC: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology trading as RMIT University 49 781 030 034 Registered for GST YES ITC 100% Period of Insurance: From: 4.00pm 1 November 2015 To: 4.00pm 1 November 2016 Both Local Standard Time at the Insured’s head office Indemnity: Legally liability of the Insured to indemnify the Host Employer for any increased Workers’ Compensation premiums under the terms of any agreement resulting from personal injury of any student whilst engaged in practical training occurring during a period of practical training by a student of the Insured in connection with such practical training activities. -

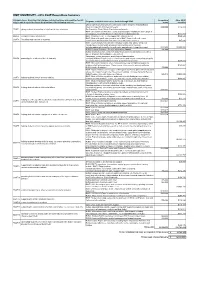

2016 SSAF Expenditure Summary

RMIT UNIVERSITY - 2016 SSAF Expenditure Summary Allowable items: A provider that charges a student services and amenities fee will Competitive Other SSAF Programs, activities and services funded through SSAF only be able to spend the fee on the provision of the following services grants spending O'Book operations, honorariums, publication (online and print) and distribution Orientation specific Activities and events $100,000 $114,993 SSAF1 giving students information to help them in their orientation Re Orientation Week (Week 5) activities and events RMIT: Orientation and transition events and campaigns including Welcome Days at all campuses, New to Melbourne Festival for international students $482,713 SSAF2 caring for children of students; RMIT: Childcare Centre in city (approx 30% student users) $320,548 RMIT: Student Legal Service provided out of RMIT Connect offers free and SSAF3 Providing legal services to students; confidential legal information and advice on a wide-range of issues $87,846 RMIT: Counselling Service provides individual counselling, advice on special consideration, mental health promotion and referral to other services. Includes additional counsellor for on-the-day appointments (competitive grant) $108,459 $1,655,853 RUSU Postgrad Program – Events, Information, Support $36,000 RUSU All activities and events from student run advocacy and welfare collectives: Queer, Womyns, Post-Graduate, Environment Campaigns, events, programs, marketing and administration. SSAF4 promoting the health or welfare of students; Compass Welfare Drop-In Centre: referral service and central communications point for internal and external welfare services, programs and outreach $238,832 RMIT: Multi-faith Chaplaincy offers compassionate help and spiritual support for students of all faiths and none. -

RMIT 2012 Annual Report

TED C L T A R 2012 ANNU REPO GLOBAL URBAN CONNE RMIT UNIVERSITY » ANNuaL REPOrt 2012 » GLOBAL / URBAN / CONNECTED www.rmit.edu.au OBJECTS OF RMIT UNIVERSITY Office of the Chancellor Dr Ziggy Switkowski Extract from the RMIT Act 2010: GPO Box 2476 Melbourne VIC 3001 The objects of the University include: Australia (a) to provide and maintain a teaching and (f) to use its expertise and resources to involve Tel. +61 3 9925 2008 learning environment of excellent quality Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people Fax +61 3 9925 3939 offering higher education at an international of Australia in its teaching, learning, research standard; and advancement of knowledge activities (b) to provide vocational education and training, and thereby contribute to: further education and other forms of (i) realising Aboriginal and Torres Strait 14 March 2013 education determined by the University to Islander aspirations support and complement the provision of (ii) the safeguarding of the ancient and higher education by the University; rich Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (c) to undertake scholarship, pure and cultural heritage; applied research, invention, innovation, (g) to provide programs and services in a way education and consultancy of international that reflects principles of equity and social standing and to apply those matters to justice; the advancement of knowledge and to the benefit of the well-being of the Victorian, (h) to confer degrees and grant diplomas, The Hon Peter Hall MLC Australian and international communities; certificates, licences and other awards; Minister for Higher Education and Skills (d) to equip graduates of the University to excel (i) to utilise or exploit its expertise and 2 Treasury Place in their chosen careers and to contribute to resources, whether commercially or EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 the life of the community; otherwise. -

General Liability – Primary $50M

GENERAL LIABILITY – PRIMARY $50M Named Insured: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology trading as RMIT University, its subsidiaries and its controlled entities; including RMIT Foundation; RMIT Link; RMIT Training Pty Ltd and RMIT Training Pty Ltd operating as RMIT Training Middle East; Spatial Vision Innovations Pty Ltd; RMIT Vietnam Holdings Pty Ltd; RMIT University Vietnam Limited Liability Company trading as RMIT International University Vietnam; Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Spain, S.L. trading as RMIT Europe; and RMIT Student Union trading as RMIT University Student Union Contractors and coaches of RMIT Link Description of Business: All activities of the Insured (a) now, (b) in the past including their predecessors in business and prior activities which have ceased or have been disposed of to the extent the Insured retains a legal liability, (c) in the future, including (i) Principally education; training; teaching; research; testing and development; experimentation; consulting and other professional services; property owners and occupiers; hall and facility hire; sporting activities, adventure activities and sporting amenities; cultural activities; sleeping accommodation; student, staff and alumni supporting services; contracted teaching, coaching, mentoring and/or instruction services, dance training, creative arts training and workshop facilitation services, performing arts training, performing arts sets and sound design; and any other occupations incidental thereto, (ii) any activity where the Insured is deemed to -

— Sustainability Annual Report 2017 — Table of Contents

RMIT Sustainability Committee — Sustainability Annual Report 2017 — Table of Contents RMIT Sustainability Annual Report 2017 About this report 4 Message from the Vice Chancellor 6 About RMIT 7 Stakeholder Engagement 10 Supporting sustainable Students 12 Creating impact 15 Sustainability in Tertiary Education 19 Ready for work and enterprise 22 Living our values 25 Empowering our people 30 Sustainable built environment 36 Sustainable operations 42 Our material topics and impacts 48 GRI reporting principles 49 GRI content index 50 — — 1. About this Report: 1.4 Highlights 1.1 Report Scope 1.2 Materiality 1.3 Our Sustainability Context This is RMIT University’s third Our approach to developing the content Following the content determination and annual sustainability report, for our report has been informed by the materiality assessment the key issues spanning the calendar year from GRI’s Reporting Principles for defining identified were: 2017 marked the 130-year anniversary of the founding report content - stakeholder inclusiveness, 1 January to 31 December 2017 • Ready for life and work of RMIT University sustainability context, materiality and and we will continue to report • Research impact completeness. It has also been informed annually. The report documents • Green buildings and infrastructure by the principles of the AA1000 standard our progress, highlights our • Learning and teaching 20 students joined our new Sustainability Ambassadors Program which provides guidance to organisations • Student health, safety and wellbeing key achievements and sets our to identify and respond to issues in • Empowering staff sustainability goals for sustainability. In 2017 we undertook a Our new Sustainability Space opened on the City campus • Governance the following year. -

City Campus Buildings Not on This Map: CITY CAMPUS » Building 154 (Royal Dental Hospital, 720 Swanston Street, Carlton) Queensberry Street LEGEND 55 a 56 a Library

City campus buildings not on this map: CITY CAMPUS » Building 154 (Royal Dental Hospital, 720 Swanston Street, Carlton) Queensberry Street LEGEND 55 A 56 A Library Wheelchair access B 76 B 43 55 Building number 74 57 Hall Landmark C 69 C 71 S Security 42 95 45 P Parking D 70 D Earl Street Secure bike parking Car Orr Str E 78 66 L E ygon St digan Stre 94 89 93 73 F 75 50 eet 96 F Design Hub 53 r RMIT VILLAGE 44 eet 47 91 97 98 et 52 46 y G 100 G Ro a l l 51 Pre Flemington H Victoria Street H R t d Grattan St e e tr I S I RMIT Village y Eliz rr Ly he City Baths T St gon Blackwood St a 105 beth St 13 J J 11 Victoria St 9 K K RMIT University Franklin St Russell St S Peel St Bowen Str Old Melbourne Gaol 14 Swan L Russell Street L et 15 obe St s Tr ton St 7 La 39 12 M 49 Alumni M Franklin Stre eet 19 10 5 Courtyard 80 N Stewart Stre N Swanston Academic Kaleide Theatre RMIT BOURKE ST Building 3 8 21 20 6 O 85 81 O Bourke Street Swanston St 108 » et RMIT Connect Swanston Street A’Beckett 101 P 88 Urban Space 4 P 37 28 1 circle • 24 • 30 t « trams: Q ee 16 Q reet Storey Hall Ormond Statue 38 2 A’Beckett Str 24 R 22 R « trams: Info Corner Little Collins Street S obe Stre83et S Tr 1 • 3 Campus Stor e Victoria State Library • Little La 5 • 6 • 8 T T e Elizabeth Str RMIT Capitol Theatr • 16 • 64 • 72 113 U U Produced from information supplied by Property Services.