Nerdling Nuclear Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, May 1988 Seattle University, Seattle, WA Master of Science in Technical Management, May 1997 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Master of Arts in International Science and Technology Policy, May 2009 The George Washington University, Washington, DC A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Kathryn Newcomer Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 26, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Dissertation Research Committee: Kathryn Newcomer, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, Dissertation Director Philippe Bardet, Assistant Professor, -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

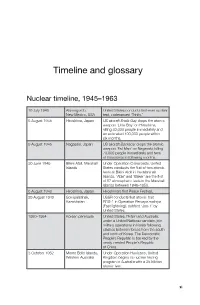

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

The Question of Reducing the Threat Posed by Nations Possessing

Mesaieed International School Model United Nations Forum: General Assembly 1 Issue: The Question of reducing threat posed by nations possessing nuclear Weapons. Student Officer: Subhan Khan Position: Deputy Chair Introduction The issue of nuclear weapons has been an ever-present issue within the world and was the first issue adopted by the UN (United Nations) in 1946. Nuclear armaments when detonated have devastating effects both environmentally and socio-economically via the fallout that it left behind from the bomb exploded. Many nations throughout the world are working to combat the issue, and the dismantling of all these weapons would be the perfect solution to all these issues, but this would be very difficult to do. Over 14,900 reported missiles remain on the Earth, and the decommissioning of all these weapons would be a feat for the human race. There is also the issue that nuclear weapons provide a sense of security and defence to a nation as they can pose a severe threat to any potential adversaries looking to harm a country. The decommissioning of nuclear weapons is an effort to preserve peace in the world and eradicate further complications that are to arise due to the threat of atomic weapons. Nations such as the US (United States) and formally the Soviet Union are unwilling to decommission their nuclear arsenals due to the risk of an attack that may occur at any point with the invention of ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles). Definition of Key Terms WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) Regarded as a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon that is capable of causing great damage to humans, infrastructure and biological systems in the vicinity of its deployment. -

Leonard Abdale and Others

IN THE FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL WPAFCC Refs: as below WAR PENSIONS AND ARMED FORCES COMPENSATION CHAMBER Sitting at Royal Courts of Justice, Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 16th December 2016 TRIBUNALS COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007 TRIBUNAL PROCEDURE (FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL) (WAR PENSIONS AND ARMED FORCES COMPENSATION CHAMBER) RULES 2008 BEFORE: THE HON MR JUSTICE BLAKE MRS I MCCORD DR J RAYNER BETWEEN 1. LEONARD ABDALE (Deceased) ENT/00203/2015 2. DARRYL BEETON ENT/00202/2015 3. TREVOR BUTLER (Deceased) ENT/00258/2015 4. DEREK HATTON (Deceased) ENT/00200/2015 5. ERNEST HUGHES ENT/00254/2015 6. BRIAN LOVATT ENT/00201/2015 7. DAWN PRITCHARD (Deceased) ENT/00258/2015 8. LAURA SELBY ENT/00199/2015 9. DENIS SHAW (Deceased) ENT/00253/2015 10. JEAN SINFIELD ENT/00204/2015 11. DONALD BATTERSBY (Deceased) ENT/00250/2015 12. ANNA SMITH ENT/00251/2015 Appellants - and - SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE Respondent Hearing Dates: 13 to 30 June 2016 Representation: Roger Ter Haar QC and Richard Sage (instructed pro bono by HOGAN LOVELLS) for Appellants 1 to 10. Christopher Busby, Hugo Charlton and Cecilia Busby acting as pro bono lay representatives for Appellants 11-12. Adam Heppinstall and Abigail Cohen instructed by the Government Legal Department for the Respondent. TRIBUNAL’S DECISION AND REASONS The unanimous DECISION of the Tribunal is: the appeal of each appellant is dismissed save for the appeal of Leonard Abdale deceased in respect of his claim for cataracts. On this issue his appeal is allowed. INDEX TO DETERMINATION PART ONE INTRODUCTION p.5 Outline -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five. -

Nuclear Arms Race

WINDSCALE AND THE POST-WAR NUCLEAR ARMS RACE Windscale, 1956, with the impressive James Chadwick works with Major General Leslie Groves And so, Attlee decided to independently pursue Piles on the right. as part of the Manhattan Project. the research of nuclear science and creation of an atomic bomb. In 1945, he created the Gen The special relationship Churchill had so carefully 75 Committee, also known as the Atomic Bomb cultivated began to fracture after the war ended. Committee, which established the government’s Considering the new technology and information uncovered nuclear policy. He knew he would need some of during the Manhattan Project to be a joint discovery, Britain’s sharpest minds to successfully develop Britain had expected that the sharing of advancements Britain’s nuclear technology and brought some of in the nuclear field would continue in peacetime. But the the country’s most prominent scientists on board, death of Roosevelt in 1945 would mark the end of wartime fresh from their time working on the Manhattan collaboration between the two countries, as President Project. Although these scientists had gained key Truman brought to a conclusion the agreements previously experience in the States and returned home with reached with Britain and Canada, going so far as to valuable knowledge, none of them had a complete introduce the Atomic Energy Act in 1946 which classified picture of how their research came together to US atomic secrets. With this act, it became a federal create a nuclear weapon, having been limited in their offence to reveal such nuclear secrets, deeming it a matter roles. -

16 Los Alamos National Laboratory the Royal Navy’S Vanguard-Class Nuclear Submarine

16 Los Alamos National Laboratory The Royal Navy’s Vanguard-class nuclear submarine. The Vanguard-class submarines are nuclear powered and armed with Trident nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. (Photo: United Kingdom Ministry of Defense) MODERNIZING FOR THE SECOND NUCLEAR AGE The late Martin White, the author of this article, was the head of Strategic Technologies for the Ministry of Defence (MOD) of the United Kingdom (U.K.). He was tasked with ensuring that the U.K.’s defense-related nuclear science and technology capability, primarily centered at the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), is developed and maintained at a level consistent with meeting the MOD’s nuclear deterrent policy requirements. This article is a personal view, and hopefully it gives a flavor of current U.K. thinking. It reflects my thoughts on the future, what I believe is the continued importance of our nuclear deterrent, and by implication, the importance of the scientific collaborations that underpin it. The U.S. and U.K. Partnership In March 1940 a U.K. memorandum, “On the Construction of a ‘Super-bomb’ Based on a Nuclear Chain Reaction in Uranium,” resulted in the establishment that April of the Military Application of Uranium Detonation (MAUD) committee. MAUD was to evaluate the possibilities of a “super-bomb.” The following year [1941], MAUD announced it considered “the scheme for a uranium bomb . practicable and likely to lead to decisive results in war.” The United Kingdom initially started out alone, under the code name Tube Alloys. However, the scale and cost of the effort led to the recommendation that the project should be pursued under an Anglo-American effort. -

Nuclear Power in the Twenty-First Century – an Assessment (Part I)

1700 Discussion Papers Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung 2017 Nuclear Power in the Twenty-fi rst Century – An Assessment (Part I) Christian von Hirschhausen Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views of the institute. IMPRESSUM © DIW Berlin, 2017 DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research Mohrenstr. 58 10117 Berlin Tel. +49 (30) 897 89-0 Fax +49 (30) 897 89-200 http://www.diw.de ISSN electronic edition 1619-4535 Papers can be downloaded free of charge from the DIW Berlin website: http://www.diw.de/discussionpapers Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin are indexed in RePEc and SSRN: http://ideas.repec.org/s/diw/diwwpp.html http://www.ssrn.com/link/DIW-Berlin-German-Inst-Econ-Res.html Nuclear Power in the Twenty-first Century – An Assessment (Part I) Christian von Hirschhausen* Abstract Nuclear power was one of the most important discoveries of the twentieth century, and it continues to play an important role in twenty-first century discussions about the future energy mix, climate change, innovation, proliferation, geopolitics, and many other crucial policy topics. This paper addresses some key issues around the emergence of nuclear power in the twentieth century and perspectives going forward in the twenty-first, including questions of economics and competitiveness, the strategic choices of the nuclear superpowers and countries that plan to either phase out or start using nuclear power, to the diffusion of nuclear technologies and the emergence of regional nuclear conflicts in the “second nuclear age”. The starting point for our hypothesis is the observation that nuclear power was originally developed for military purposes as the “daughter of science and warfare” (Lévêque 2014, 212), whereas civilian uses such as medical applications and electricity generation emerged later as by-products. -

Military Awards

Army Regulation 600–8–22 Personnel-General Military Awards Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 25 June 2015 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 600–8–22 Military Awards This major revision, dated 25 June 2015-- o Updates guidance on reconsideration and appeal of previous award recommendations (para 1-16). o Updates and clarifies guidance for flagged Soldiers and Purple Heart entitlement (para 1-17). o Clarifies guidance on duplication of awards (para 1-19). o Adds Impact Awards guidance (1-21). o Clarifies guidance for awards recognition upon retirement and adds information for Soldiers serving under the Retiree Recall Program (para 1- 23b). o Adds guidance on notification and right to appeal upon revocation of awards (para 1-31). o Adds new Medal of Honor guidance (para 1-33). o Adds table of approval authorities for U.S. decorations for foreign military personnel (table 1-3). o Updates replacement procedures for issuing U.S. Army medals (para 1-47). o Adds new criteria for award of the Purple Heart under the provisions of Public Law 113-291 and Department of Defense Implementing Guidance (para 2-8). o Adds Operation NEW DAWN as an authorized operation for award of the Iraq Campaign Medal (para 2-17). o Clarifies criteria and type of service for award of the Humanitarian Service Medal (para 2-22). o Adds delegation of peacetime and wartime awards approval authority to deputy commanding generals (paras 3-5 and 3-6). o Removes lieutenant generals restriction for award of the Legion of Merit (table 3-2). o Add new policy for Stability Operations (para 3-7). -

Nuclear Weapons Test Effects: Debunking Popular Exaggerations That Encourage Proliferation: EMP Radiation from Nuclear Space Bursts in 1962

Nuclear weapons test effects: debunking popular exaggerations that encourage proliferation: EMP radiation from nuclear space bursts in 1962 Nuclear weapons test effects: debunking popular exaggerations that encourage proliferation ‘I did not think, I investigated.’ - Wilhelm Röntgen, discoverer of X-rays in 1895, answering Sir James Mackenzie-Davidson’s question in 1896: ‘What did you think?’ J. J. Thomson in 1894 discovered visible evidence of X-rays: glass fluorescence far from a cathode ray tube. But his expert opinion was that it was unimportant! ‘Science is the organized skepticism in the reliability of expert opinion.’ - Richard Feynman in Lee Smolin, The Trouble with Physics, Houghton-Mifflin, 2006, p. 307. Wednesday, March 29, 2006 EMP radiation from nuclear space bursts in 1962 Above: USSR Test ‘184’ on 22 October 1962, ‘Operation K’ (ABM System A proof tests) 300-kt burst at 290-km altitude near Dzhezkazgan. Prompt gamma ray- produced EMP induced a current of 2,500 amps measured by spark gaps in a 570-km stretch of 500 ohm impedance overhead telephone line to Zharyq, blowing all the protective fuses. The late-time MHD-EMP was of low enough frequency to enable it to penetrate the 90 cm into the ground, overloading a shallow buried lead and steel tape-protected 1,000-km long power cable between Aqmola and Almaty, firing circuit breakers and setting the Karaganda power plant on fire. In December 1992, the U.S. Defence Nuclear Agency spent $288,500 on contracting 200 Russian scientists to produce a 17-chapter analysis of effects from the Soviet Union’s nuclear tests, which included vital data on three underwater nuclear tests in the arctic, as well three 300 kt high altitude tests at altitudes of 59-290 km over Kazakhstan. -

1 949, the Manufacture of Atomic Weapons, and the Labour

Anglo-Arnerican Relations, 1945- 1949, the Manufacture of Atomic Weapons, and the Labour Governent of 1945 Catharine B. Grant Submitted in partial fulnlment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada December, 1999 O Copyright by Catharine B. Grant, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationaIe 1+1 ,,,da du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Our die Noae dfdrcwe The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National L&fary of Canada to Bibliotbeque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la proprieté du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts firom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son p enmission. autorisation. TabIe of Contents Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgeme~ts htroducbon Chapter 1 The Anglo-Arnericun "Special ReZutionsh@, '" 1945-1949 10 Chapter II The Anglo-Arnerican Atomic Relations and British A tomic 44 Decision-Making Structures Chapter III neAtomic Bomb and the Labour Left 93 Conclusion Appendices Bibliography The British decision in 1947 to manufacture atomic weapons was greatly inauenced by its changed international status in the post-World War II era.