The Development of Britain's Megaton Warheads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, May 1988 Seattle University, Seattle, WA Master of Science in Technical Management, May 1997 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Master of Arts in International Science and Technology Policy, May 2009 The George Washington University, Washington, DC A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Kathryn Newcomer Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 26, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Dissertation Research Committee: Kathryn Newcomer, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, Dissertation Director Philippe Bardet, Assistant Professor, -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

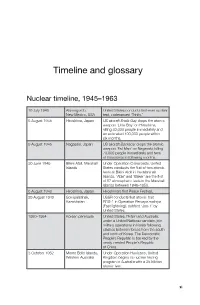

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

The Question of Reducing the Threat Posed by Nations Possessing

Mesaieed International School Model United Nations Forum: General Assembly 1 Issue: The Question of reducing threat posed by nations possessing nuclear Weapons. Student Officer: Subhan Khan Position: Deputy Chair Introduction The issue of nuclear weapons has been an ever-present issue within the world and was the first issue adopted by the UN (United Nations) in 1946. Nuclear armaments when detonated have devastating effects both environmentally and socio-economically via the fallout that it left behind from the bomb exploded. Many nations throughout the world are working to combat the issue, and the dismantling of all these weapons would be the perfect solution to all these issues, but this would be very difficult to do. Over 14,900 reported missiles remain on the Earth, and the decommissioning of all these weapons would be a feat for the human race. There is also the issue that nuclear weapons provide a sense of security and defence to a nation as they can pose a severe threat to any potential adversaries looking to harm a country. The decommissioning of nuclear weapons is an effort to preserve peace in the world and eradicate further complications that are to arise due to the threat of atomic weapons. Nations such as the US (United States) and formally the Soviet Union are unwilling to decommission their nuclear arsenals due to the risk of an attack that may occur at any point with the invention of ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles). Definition of Key Terms WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) Regarded as a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon that is capable of causing great damage to humans, infrastructure and biological systems in the vicinity of its deployment. -

Nuñez Angles

5th International Seminar on Security and Defence in the Mediterranean Multi-Dimensional Security Reports (+34) 93 302 6495 - Fax. (+34) 93 302 6495 - [email protected] (+34) 93 302 6495 - Fax. [email protected] Weapons of mass destruction in the Mediterranean: An omnidirectional threat. Jesús A. Núñez Villaverde, Balder Hageraats and Ximena Valente - Calle Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona, España Tel. Fundación CIDOB WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN: AN OMNIDIRECTIONAL THREAT Jesús A. Núñez Villaverde Co-director of the Institute of Studies on Conflicts and Humanitarian Action, IECAH Balder Hageraats Researcher at IECAH Ximena Valente Researcher at IECAH Introduction 1. Similar to the first report, the concept of WMD is used in its general understanding of having the Similarly to the first report on Weapons of mass destruction in the three basic components of nuclear, Mediterranean: current status and prospects, released in 2005, this chemical and biological weapons. In practical terms, however, the main second report (Weapons of mass destruction in the Mediterranean: an focus of this report is on nuclear omnidimensional threat) is the result of an initiative – responding to a weapons given that these are the sustained interest in matters of security and defence in the Mediterranean only ones that true fit the profile of WMD at the moment. - by the CIDOB Foundation. It is therefore fitting to mention the annual seminars on security and defence that are held in Barcelona since 2002. In line with the decision taken at the third of these meetings, the aim of this report is to facilitate – both for those attending the sessions directly as well as the wider security community interested in the region - the analysis of one of the most pressing problems on the international agenda. -

Czulda Polityka Bezpieczenstwa.Pdf

Robert Czulda – Uniwersytet Łódzki, Wydział Studiów Międzynarodowych i Politologicz- nych Zakład Teorii Polityki i Myśli Politycznej, 90–127 Łódź, ul. Składowa 41/43 RECENZENT Jarosław Gryz REDAKTOR WYDAWNICTWA UŁ Elżbieta Marciszewska-Kowalczyk SKŁAD I ŁAMANIE AGENT PR PROJEKT OKŁADKI Łukasz Orzechowski Zdjęcie wykorzystane na okładce: © Depositphotos.com/swisshippo © Copyright by Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź 2014 Wydane przez Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego Wydanie I. W.06278.13.0.D ISBN 978-83-7969-153-1 (wersja papierowa) ISBN 978-83-7969-495-2 (wersja elektroniczna) https://doi.org/10.18778/7969-153-1 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego 90-131 Łódź, ul. Lindleya 8 www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] tel. (42) 665 58 63, faks (42) 665 58 62 SPIS TREŚCI WPROWADZENIE ................................................................................................................. 7 ROZDZIAŁ I Brytyjska ocena strategiczna środowiska bezpieczeństwa ................................................... 33 Ocena zagrożeń i prognoza rozwoju sytuacji w latach 1944–1945 ............................. 33 Od nadziei do konfrontacji (1945–1947) ......................................................................... 46 Wpływ broni nuklearnej na ocenę zagrożeń ................................................................... 59 Strategia trzech fi larów a środowisko międzynarodowe (1948–1950) ......................... 71 Wojna w Korei i próby odprężenia – od obaw do nadziei (1950–1955) ..................... 94 ROZDZIAŁ II Multilateralne -

A World First Which Affects Everybody D.J

A WORLD FIRST WHICH AFFECTS EVERYBODY D.J. Farrar O.B.E. , M.A., C.Eng., F.R.Ae.S., Hon. F.I.E.D. An historic event is one that affects you, and affects everybody. How many computers do you have in your house? Not the one you use, the ones that control things - in the refrigerator, in your car, in the washing machine, etc. Recently the professional institutions have been researching where and how Process Control by Computer was achieved for the first time. The answer is that it was achieved in Britain, and the new aero museum in Bristol will feature it because it has been rebuilt by a team of enthusiasts. It controls an anti aircraft fire unit and the Bloodhound 2 guided weapon, both on the ground and in flight, and was one reason for the very long service life it had. The computer involved is the Ferranti Argus. HOW IT CAME ABOUT Digital computers for process control were developed at the end of the 1950s. They had different design objectives from computers for scientific or commercial use. The Ferranti Argus was among the first computers world- wide used for direct digital control. The Argus was invented at Ferranti's Wythenshawe Automation Division, Manchester, by Maurice Gribble. If credit for 'invention' must be assigned, it should go to the person or team that first had a clear vision of the principle, saw its potential, fought for its acceptance and brought it fully into satisfactory use. The Ferranti Argus computer was built by an automation group, not a computer division. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

The Bloodhound Guided Missile and the Hawker Harrier “Jump Jet”

The University of Manchester Research Practice in Communities: how engineers create solutions the Bloodhound Guided Missile and the Hawker Harrier “jump jet”. Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Aylen, J., & Pryce, M. (2011). Practice in Communities: how engineers create solutions the Bloodhound Guided Missile and the Hawker Harrier “jump jet”. In host publication Published in: host publication Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Draft for joint Herbert Simon Institute/Manchester Institute of Innovation Research Seminar, 1st April 2011 Practice in Communities: how engineers create solutions ‐ the Bloodhound Guided Missile and the Hawker Harrier “jump jet”. Jonathan Aylen* and Mike Pryce* Manchester Institute of Innovation Research Manchester Business School University of Manchester “Every aeroplane is different ‐ a self‐optimising shambles” Ralph Hooper, Harrier project designer Aerospace engineers face the task of developing a project from overall design concept through to working prototype and on into sustained use. -

Roy Dommett Interviewed by Dr Thomas Lean

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Roy Dommett Interviewed by Dr Thomas Lean C1379/14 © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk . © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/14 Collection title: An Oral History Of British Science Interviewee’s Dommett Title: Mr surname: Interviewee’s Roy Sex: Male forename: Occupation: Rocket scientist, Date and place of birth: 25th June 1933 aeronautical engineer. Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Painter and decorator Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks (from – to): March 18 (1-3), April 13 (4-5), April 20 (6-10), 20 July (11-14), 16 September (15-19) 2010 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home, Fleet. Name of interviewer: Thomas Lean Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 on secure digital [tracks 1 - 10] and Marantz PMD660 on compact flash [tracks 11 - 19] Recording format : WAV 24 bit 48 kHz (tracks 1 - 10), WAV 16 bit 48 kHz (Tracks 11-19). -

Consequences of an Accident Involving Nuclear Weapons

ThisreportisdedicatedtothememoryofJohn Ainslie, whose persistent and meticulous research exposedmanyoftheaccidentsdescribedhere CONTENTS REPORT HEADLINES 2 FOREWORD 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INTRODUCTION 8 THE PRODUCTION AND MANUFACTURE OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS 14 CASE STUDY 1: ‘An accident waiting to happen: fire at Windscale .......... 25 ON THE ROAD: ACCIDENTS DURING THE TRANSPORT OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS 30 CASE STUDY 2: Slipping off the road ............................. 39 STORAGE AND HANDLING OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS 42 CASE STUDY 3: Rough handling at RAF Bruggen ...................... 46 IN THE FIELD: INCIDENTS INVOLVING AIRCRAFT AND SHIPS 48 CASE STUDY 4: Nuclear weapons and the Falklands War ................ 55 UNDER THE WAVES: ACCIDENTS INVOLVING NUCLEAR-ARMED SUBMARINES 58 CASE STUDY 5: Collision in the ocean depths.........................73 SECRETS AND SPIES: NUCLEAR SECURITY 76 CASE STUDY 6: “We’re hijacking this submarine. Take us to Cuba.” ..........87 OVER HERE: ACCIDENTS INVOLVING US NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN THE UK 90 CASE STUDY 7: Broken Arrow at Lakenheath......................... 98 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 100 AFTERWORD 103 APPENDIX 104 GLOSSARY 106 REPORT AUTHOR: PETER BURT 1 REPORT HEADLINES Whywedidthisstudy: • The following factors have all contributed to accidents involving British nuclear weapons: This report presents the accident record of the ` Failures caused as equipment reaches UK’s nuclear weapons programme over its 65 the end of its operating life. year history. Our aim in doing this is simple: to remind the public of the risks posed by nuclear ` Equipment in short supply or overused. weapons, and to alert politicians and decision ` Operations hurried or conducted makers to the need to eliminate these risks. under pressure. ` Workers failing to follow even the What we found: strictest instructions and procedures. -

A History of the United Kingdom's WE 177 Nuclear Weapons Programme

MARCH 2019 A History of the United Kingdom’s WE 177 Nuclear Weapons Programme From Conception to Entry into Service 1959– 1980 Dr John R. Walker © The British American Security Information Council (BASIC), 2018 All images licenced for reuse under Creative Commons 2.0 and Wikimedia Commons or with the approriate permission and sourcing. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility The British American Security of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of BASIC. Information Council (BASIC) 17 Oval Way All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be London SE11 5RR reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or Charity Registration No. 1001081 any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. T: +44 (0) 20 3752 5662 www.basicint.org Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. The Author BASIC Dr John R Walker is the Head of the Arms Control The British American Security Information Council and Disarmament Research Unit (ACDRU) at the (BASIC) is an independent think tank and registered Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London, and charity based in Central London, promoting has worked in ACDRU since March 1985. He innovative ideas and international dialogue on currently focuses on the Chemical Weapons nuclear disarmament, arms control, and Convention (CWC), the Biological and Toxin nonproliferation. Since 1987, we’ve been at the Weapons Convention (BTWC), the Comprehensive forefront of global efforts to build trust and Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), the UN Secretary- cooperation on some of the world’s most General’s Mechanism, and arms control verification progressive global peace and security initiatives, more generally.