Testing the Bomb: Maralinga and Australian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, May 1988 Seattle University, Seattle, WA Master of Science in Technical Management, May 1997 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Master of Arts in International Science and Technology Policy, May 2009 The George Washington University, Washington, DC A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Kathryn Newcomer Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 26, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Dissertation Research Committee: Kathryn Newcomer, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, Dissertation Director Philippe Bardet, Assistant Professor, -

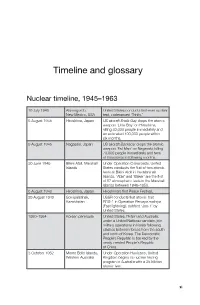

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit Trachoma Surveillance Report 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NATIONAL TRACHOMA SURVEILLANCE AND REPORTING UNIT TRACHOMA SURVEILLANCE REPORT 2008 AUGUST 2009 Prepared by Ms Betty Tellis Ms Kathy Fotis Mr Ross Dunn Professor Jill Keeffe Professor Hugh Taylor Centre for Eye Research Australia, University of Melbourne National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit Trachoma Surveillance Report 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit’s third Surveillance Report 2008 was compiled using data collected and/or reported by the following organisations and departments. STATE AND TERRITORY CONTRIBUTIONS NORTHERN TERRITORY • Australian Government Emergency Intervention (AGEI) • Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) • Centre for Disease Control, Northern Territory Department of Health and Families, Northern Territory • Healthy School Age Kids (HSAK) program: Top End • HSAK: Central Australia SOUTH AUSTRALIA • Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia, Eye Health and Chronic Disease Specialist Support Program (EH&CDSSP) • Country Health South Australia • Ceduna/Koonibba Health Service • Nganampa Health Council • Oak Valley (Maralinga Tjarutja) Health Service • Pika Wiya Health Service • Tullawon Health Service • Umoona Tjutagku Health Service WESTERN AUSTRALIA • Communicable Diseases Control Directorate, Department of Health, Western Australia • Population Health Units and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services staff in the Goldfields, Kimberley, Midwest and Pilbara regions OTHER CONTRIBUTIONS ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE • Institute of Medical Veterinary -

Indigenous Design Issuesceduna Aboriginal Children and Family

INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWELDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND “BEST PRACTICE„ DESIGN ....................................................10 The Design of Early Learning, Child-care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ..................................................................................................................................10 Conceptions of Quality ........................................................................................................ 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ..................................12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................................. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

(G-FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater Recharge

Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID and Davies PJ Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839‐2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science‐based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08‐8303 8952 e‐mail: [email protected] Citation Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID, and Davies PJ, 2013, Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6, Adelaide, South Australia Copyright © 2013 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Disclaimer The Participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research and does not warrant or represent the completeness of any information or material in this publication. -

A Collaborative History of Social Innovation in South Australia

Hawke Research Institute for Sustainable Societies University of South Australia St Bernards Road Magill South Australia 5072 Australia www.unisa.edu.au/hawkeinstitute © Rob Manwaring and University of South Australia 2008 A COLLABORATIVE HISTORY OF SOCIAL INNOVATION IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA Rob Manwaring∗ Abstract In this paper I outline a collaborative history of social innovation in South Australia, a state that has a striking record of social innovation. What makes this history so intriguing is that on the face of it, South Australia would seem an unlikely location for such experimentation. This paper outlines the main periods of innovation. Appended to it is the first attempt to collate all these social innovations in one document. This paper is unique in that its account of the history of social innovation has been derived after public consultation in South Australia, and is a key output from Geoff Mulgan’s role as an Adelaide Thinker in Residence.1 The paper analyses why, at times, South Australia appears to have punched above its weight as a leader in social innovation. Drawing on Giddens’ ‘structuration’ model, the paper uses South Australian history as a case study to determine how far structure and/or agency can explain the main periods of social innovation. Introduction South Australia has a great and rich (albeit uneven) history of social innovation, and has at times punched above its weight. What makes this history so intriguing is that on the face of it, South Australia is quite an unlikely place for such innovation. South Australia is a relatively new entity; it has a relatively small but highly urbanised population, and is geographically isolated from other Australian urban centres and other developed nations. -

The Question of Reducing the Threat Posed by Nations Possessing

Mesaieed International School Model United Nations Forum: General Assembly 1 Issue: The Question of reducing threat posed by nations possessing nuclear Weapons. Student Officer: Subhan Khan Position: Deputy Chair Introduction The issue of nuclear weapons has been an ever-present issue within the world and was the first issue adopted by the UN (United Nations) in 1946. Nuclear armaments when detonated have devastating effects both environmentally and socio-economically via the fallout that it left behind from the bomb exploded. Many nations throughout the world are working to combat the issue, and the dismantling of all these weapons would be the perfect solution to all these issues, but this would be very difficult to do. Over 14,900 reported missiles remain on the Earth, and the decommissioning of all these weapons would be a feat for the human race. There is also the issue that nuclear weapons provide a sense of security and defence to a nation as they can pose a severe threat to any potential adversaries looking to harm a country. The decommissioning of nuclear weapons is an effort to preserve peace in the world and eradicate further complications that are to arise due to the threat of atomic weapons. Nations such as the US (United States) and formally the Soviet Union are unwilling to decommission their nuclear arsenals due to the risk of an attack that may occur at any point with the invention of ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles). Definition of Key Terms WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) Regarded as a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon that is capable of causing great damage to humans, infrastructure and biological systems in the vicinity of its deployment. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

A Preliminary Study of Pitch and Rhythm in Pitjantjatjara

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF PITCH AND RHYTHM IN PITJANTJATJARA. Marija Tabain (La Trobe University, Melbourne), Janet Fletcher (University of Melbourne), Christian Heinrich (Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich) Pitjantjatjara is a dialect of the greater Western Desert language, spoken mainly in the north-west of South Australia, but extending north into the Northern Territory, and west into Western Australia (Douglas 1964). Like most Australian languages, Pitjantjatjara has been analysed as a stress language (trochaic); however relatively little is known about the intonational system of this language. We present a preliminary analysis of the prosodic structure of Pitjantjatjara based on three female speakers reading two different texts – the Walpa Ulpariranya munu Tjintunya (South Wind and the Sun) passage, and the Nanikuta (Three Billy Goats) text. Our first result suggests that the shape and temporal alignment of major pitch movements perform a largely demarcative function, aligning with the metrically strong first syllable in a word. There is mixed evidence, however, that strong syllables are longer or have more "peripheral" vowels: differences in strong vs. weak syllable duration are text- dependent, while the formant patterns for the three vowel phonemes /i, a, u/ suggest subtle formant differences, rather than categorical changes in vowel quality, according to strong vs. weak syllable. We also consider the traditional rhythm metrics (e.g. vocalic nPVI and intervocalic rPVI). These suggest that Pitjantjatjara is a stress-based language. However, as noted above, Pitjantjatjara does not have vowel reduction in weak syllables, and in addition, it has a predominantly CV syllable structure. Moreover, Australian languages such as Pitjantjatjara have a high proportion of sonorants in their phoneme inventory (Butcher 2006), and despite the mainly CV syllable structure, sonorant coda consonants are possible and not infrequent. -

Grievability and Nuclear Memory | 379

Grievability and Nuclear Memory | 379 Grievability and Nuclear Memory Jessie Boylan Nuclear Wounds Without grievability, there is no life, or, rather, there is something living that is other than life. Instead, “there is a life that will never have been lived,” sustained by no regard, no testimony, and ungrieved when lost. The apprehension of grievability precedes and makes possible the apprehension of precarious life. —Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (2009) ince 1945, nuclear weapons have been tested on all continents except for South America and Antarctica. Although “it is the nature of bombing to Sbe indiscriminate,”1 Aboriginal, Indigenous, and First Nations people have been the disproportionate victims of these weapons. They also continue to face nuclear waste dumps, uranium mines, and other nuclear projects on their land. This radioactive colonialism ensures that violence persists and is etched into the knowledge of people, place, and country, and that the single “event” of a nuclear detonation is far from over. Official records provide ample evidence to document how state policies, practices, and attitudes marked Aboriginal people as not fully human. For example, the Maralinga nuclear test site in Australia was “chosen on the false assumption that the area was not used by its traditional Aboriginal owners.”2 People living downwind (“downwinders”) of the Nevada Test Site in Utah during the US atomic weapons testing program,3 including First Nations communities, were considered “a low-use segment of the population.”4 These racist assumptions and statements, one tiny example from the archive of the nuclear landscape, constructed the people (and the lands they inhabited) as disposable. -

Reclaiming the Kaurna Language: a Long and Lasting Collaboration in an Urban Setting

Vol. 8 (2014), pp. 409-429 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4613 Series: The Role of Linguists in Indigenous Community Language Programs in Australia1 Reclaiming the Kaurna language: a long and lasting collaboration in an urban setting Rob Amery University of Adelaide A long-running collaboration between Kaurna people and linguists in South Australia be- gan in 1989 with a songbook. Following annual community workshops and the estab- lishment of teaching programs, the author embarked on a PhD to research historical sources and an emerging modern language based on these sources. In response to numer- ous requests for names, translations and information, together with Kaurna Elders Lewis O’Brien and Alitya Rigney, the author and others formed Kaurna Warra Pintyandi (KWP) in 2002. It is a monthly forum where researchers, and others interested in Kaurna lan- guage, can meet with Kaurna people to discuss their concerns. KWP, based at the Univer- sity of Adelaide, is not incorporated and attendance of meetings is voluntary. The com- mittee has gained a measure of credibility and respect from the Kaurna community, gov- ernment departments and the public and has recently signed a Memorandum of Under- standing with the University of Adelaide. However, KWP and the author sit, uneasily at times, at the intersection between the University and the community. This paper explores the nature of collaboration between Kaurna people and researchers through KWP in the context of reliance on historical documentation, much of which is open to interpretation. Linguistics provides some of the skills needed for interpretation of source materials.