Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 29

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 29 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS BATTLE OF BRITAIN DAY. Address by Dr Alfred Price at the 5 AGM held on 12th June 2002 WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE LUFTWAFFE’S ‘TIP 24 AND RUN’ BOMBING ATTACKS, MARCH 1942-JUNE 1943? A winning British Two Air Forces Award paper by Sqn Ldr Chris Goss SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SIXTEENTH 52 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 12th JUNE 2002 ON THE GROUND BUT ON THE AIR by Charles Mitchell 55 ST-OMER APPEAL UPDATE by Air Cdre Peter Dye 59 LIFE IN THE SHADOWS by Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker 62 THE MUNICIPAL LIAISON SCHEME by Wg Cdr C G Jefford 76 BOOK REVIEWS. 80 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal -

Aviation Classics Magazine

Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 taxies towards the camera in impressive style with a haze of hot exhaust fumes trailing behind it. Luigino Caliaro Contents 6 Delta delight! 8 Vulcan – the Roman god of fire and destruction! 10 Delta Design 12 Delta Aerodynamics 20 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan 62 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.6 Nos.1 and 2 64 RAF Scampton – The Vulcan Years 22 The ‘Baby Vulcans’ 70 Delta over the Ocean 26 The True Delta Ladies 72 Rolling! 32 Fifty years of ’558 74 Inside the Vulcan 40 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.3 78 XM594 delivery diary 42 Vulcan display 86 National Cold War Exhibition 49 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.4 88 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.7 52 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.5 90 The Council Skip! 53 Skybolt 94 Vulcan Furnace 54 From wood and fabric to the V-bomber 98 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.8 4 aviationclassics.co.uk Left: Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 caught in some atmospheric lighting. Cover: XH558 banked to starboard above the clouds. Both John M Dibbs/Plane Picture Company Editor: Jarrod Cotter [email protected] Publisher: Dan Savage Contributors: Gary R Brown, Rick Coney, Luigino Caliaro, Martyn Chorlton, Juanita Franzi, Howard Heeley, Robert Owen, François Prins, JA ‘Robby’ Robinson, Clive Rowley. Designers: Charlotte Pearson, Justin Blackamore Reprographics: Michael Baumber Production manager: Craig Lamb [email protected] Divisional advertising manager: Tracey Glover-Brown [email protected] Advertising sales executive: Jamie Moulson [email protected] 01507 529465 Magazine sales manager: -

1 P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS' IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference Number

P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: GB1741/P247 Alternative reference number: Title: Musketry Regulations, Part II Dates of creation: 1910 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 1 volume Format: Paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: The War Office Administrative history: The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence. The name "War Office" is also often given to the former home of the department, the Old War Office Building on Horse Guards Avenue, London. The War Office declined greatly in importance after the First World War, a fact illustrated by the drastic reductions in its staff numbers during the inter-war period. On 1 April 1920, it employed 7,434 civilian staff; this had shrunk to 3,872 by 1 April 1930. Its responsibilities and funding were also reduced. In 1936, the government of Stanley Baldwin appointed a Minister for Co-ordination of Defence, who worked outside of the War Office. When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, he bypassed the War Office altogether and appointed himself Minister of Defence (though there was, curiously, no ministry of defence until 1947). Clement Attlee continued this arrangement when he came to power in 1945 but appointed a separate Minister of Defence for the first time in 1947. In 1964, the present form of the Ministry of Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives 1 Defence was established, unifying the War Office, Admiralty, and Air Ministry. -

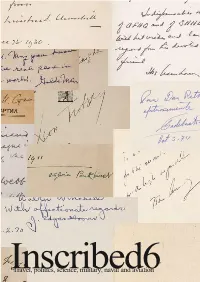

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Freeman's Folly

Chapter 9 Freeman’s Folly: The Debate over the Development of the “Unarmed Bomber” and the Genesis of the de Havilland Mosquito, 1935–1940 Sebastian Cox The de Havilland Mosquito is, justifiably, considered one of the most famous and effective military aircraft of the Second World War. The Mosquito’s devel- opment is usually portrayed as being a story of a determined and independent aircraft company producing a revolutionary design with very little input com- ing from the official Royal Air Force design and development process, which normally involved extensive consultation between the Air Ministry’s technical staff and the aircraft’s manufacturer, culminating in an official specification being issued and a prototype built. Instead, so the story goes, de Havilland’s design team thought up the concept of the “unarmed speed bomber” all by themselves and, despite facing determined opposition from the Air Ministry and the raf, got it adopted by persuading one important and influential senior officer, Wilfrid Freeman, to put it into production (Illustration 9.1).1 Thus, before it proved itself in actuality a world-beating design, it was known in the Ministry as “Freeman’s Folly”. Significantly, even the UK Official History on the “Design and Development of Weapons”, published in 1964, perpetuated this explanation, stating that: When … [de Havilland] found itself at the beginning of the war short of orders and anxious to contribute to the war effort they proceeded to design an aeroplane without any official prompting from the Air Minis- try. They had to think out for themselves the whole tactical and strategic purpose of the aircraft, and thus made a number of strategic and tactical assumptions which were not those of the Air Staff. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

Sac's Kissing Cousins

Ground crewmen bring a British RAF Bomber Command Vulcan V-bomber to a high state of readiness. In case of nuclear war bombers of the British V-force would likely spearhead any retaliatory attack. Vuleans, the world's largest delta. wing bombers, carry either conventional or nuclear bombs internally and one Blue Steel standoff weapon externally. Although there are some misgivings about the future, today's British RAF Bomber Command is decidedly a viable force for the 1960s. Here is a report on the powerful capabilities of the United Kingdom's nuclear aerospace force . SAC'S KISSING COUSINS HE officer commanding, seated in the War Room of his operational control center, reached for the T red phone and spoke an order into it which ener- gized his widely dispersed command. The order was a single word—Scramble! A small but superbly trained band of men sprang into action. With machine precision, they raced By Richard Clayton Peet through prescribed checkout procedures, preparing their planes for flight. Jet engines began their roar. Seconds later, hundreds of aircraft were on the roll. In less than two minutes, a giant nuclear retaliatory armada was airborne. Most Americans would immediately conclude that the situation described was taking place in our own Strategic Air Command. We have become accustomed 28 AIR FORCE Magazine • January 1964 Sir John Grandy, Bomber Commander CinC, credits Valiant, first V-bomber, today is used primarily as a tanker. technical innovation and high crew proficiency with Here a Valiant refuels one of the Vulcans that made the first keeping Bomber Command a viable force in the 1960s. -

Cruise Missiles Post World War II

Cruise missiles milestones MILE post STONES World War II Dr Carlo Kopp THE BASIC TECHNOLOGY AND OPERATIONAL CONCEPT OF MODERN CRUISE MISSILES EMERGED DURING THE LATE 1960S, at the peak of the Cold War era. This type of weapon was exemplified by the RGM-109 Tomahawk series, the AGM-86C/D CALCM, the AGM-158 JASSM, and the Russian Kh-55SM Granat. Much less known is the generation of cruise missile technology that supplanted the 1940s era FZG-76/V-1 and its Russian and American clone variants. A good number of the former Soviet weapons of this generation remain in use, some still in production. The aim of all cruise missile designs is to provide a weapon that can strike at a target while not exposing the launch platform to attack by enemy defences, whether the launch platform is an aircraft, surface warship, submarine or ground vehicle. Key parameters in the design of any cruise missile are its standoff range, its accuracy and its survivability against target defences. Increasing standoff range reduces risk to the launch platform while increasing accuracy and survivability reduces the number of launches required to achieve desired effect. The economics of bombardment are simple: the more expensive the weapon employed, the smaller the war stock available for combat at any time, and the longer it takes to replenish this war stock once expended. Northrop SM-62 Snark strategic cruise missile. This enormous 50,000 lb plus GLCM was built to directly attack the Soviet Union from US basing. It introduced the fi rst stellar-inertial guidance system in a cruise missile. -

NUCLEAR WEAPONS EFFECTS Introduction: the Energy Characteristics and Output from Nuclear Weapons Differ Significantly from Conve

NUCLEAR WEAPONS EFFECTS Introduction: The energy characteristics and output from nuclear weapons differ significantly from conventional weapons. Nuclear detonations exhibit much higher temperature within the fireball and produce peak temperatures of several hundred million degrees and intense x-ray heating that results in air pressure pulses of several million atmospheres. Conventional chemical explosions result in much lower temperatures and release the bulk of their energy as air blast and shock waves. In an atmospheric detonation, such as was deployed in Japan, it is the blast and thermal component of the nuclear explosion that is the major factor in destruction and death, not nuclear radiation, as the public believes. The effective range of immediate harm to humans from nuclear radiation from the atmospheric explosion is much less than the effective range from blast and thermal heating. In order to limit the discussion of weapons effects to elementary terms, this discussion is based upon a single worst-case scenario. Probably the largest weapon that might be employed against a population would have a yield of less than one-megaton (or 1 million tons of TNT equivalent energy or simply 1 MT). However, a crude terrorist nuclear device would probably be in the range of a few thousand tons of TNT equivalent energy or a few KT). The discussion here is based upon a nuclear detonation of 1 MT. Yield: The destructive power of a nuclear weapon, when compared to the same amount of energy produced by TNT is defined as the ‘yield’ of the nuclear weapon. A 20-kiloton (KT) weapon, such as was detonated over Japan in World War II was equivalent in energy yield to 20,000 tons of TNT. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

The Effects of Nuclear War

The Effects of Nuclear War May 1979 NTIS order #PB-296946 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-600080 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D C, 20402 — Foreword This assessment was made in response to a request from the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations to examine the effects of nuclear war on the populations and economies of the United States and the Soviet Union. It is intended, in the terms of the Committee’s request, to “put what have been abstract measures of strategic power into more comprehensible terms. ” The study examines the full range of effects that nuclear war would have on civilians: direct effects from blast and radiation; and indirect effects from economic, social, and politicai disruption. Particular attention is devoted to the ways in which the impact of a nuclear war would extend over time. Two of the study’s principal findings are that conditions would con- tinue to get worse for some time after a nuclear war ended, and that the ef- fects of nuclear war that cannot be calculated in advance are at least as im- portant as those which analysts attempt to quantify. This report provides essential background for a range of issues relating to strategic weapons and foreign policy. It translates what is generally known about the effects of nuclear weapons into the best available estimates about the impact on society if such weapons were used. It calls attention to the very wide range of impacts that nuclear weapons would have on a complex industrial society, and to the extent of uncertainty regarding these impacts. -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1.