1 949, the Manufacture of Atomic Weapons, and the Labour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, May 1988 Seattle University, Seattle, WA Master of Science in Technical Management, May 1997 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Master of Arts in International Science and Technology Policy, May 2009 The George Washington University, Washington, DC A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Kathryn Newcomer Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 26, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Dissertation Research Committee: Kathryn Newcomer, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, Dissertation Director Philippe Bardet, Assistant Professor, -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

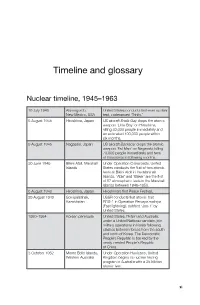

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

The Question of Reducing the Threat Posed by Nations Possessing

Mesaieed International School Model United Nations Forum: General Assembly 1 Issue: The Question of reducing threat posed by nations possessing nuclear Weapons. Student Officer: Subhan Khan Position: Deputy Chair Introduction The issue of nuclear weapons has been an ever-present issue within the world and was the first issue adopted by the UN (United Nations) in 1946. Nuclear armaments when detonated have devastating effects both environmentally and socio-economically via the fallout that it left behind from the bomb exploded. Many nations throughout the world are working to combat the issue, and the dismantling of all these weapons would be the perfect solution to all these issues, but this would be very difficult to do. Over 14,900 reported missiles remain on the Earth, and the decommissioning of all these weapons would be a feat for the human race. There is also the issue that nuclear weapons provide a sense of security and defence to a nation as they can pose a severe threat to any potential adversaries looking to harm a country. The decommissioning of nuclear weapons is an effort to preserve peace in the world and eradicate further complications that are to arise due to the threat of atomic weapons. Nations such as the US (United States) and formally the Soviet Union are unwilling to decommission their nuclear arsenals due to the risk of an attack that may occur at any point with the invention of ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles). Definition of Key Terms WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) Regarded as a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon that is capable of causing great damage to humans, infrastructure and biological systems in the vicinity of its deployment. -

Historic Barriers to Anglo-American Nuclear Cooperation

3 HISTORIC BARRIERS TO ANGLO- AMERICAN NUCLEAR COOPERATION ANDREW BROWN Despite being the closest of allies, with shared values and language, at- tempts by the United Kingdom and the United States to reach accords on nuclear matters generated distrust and resentment but no durable arrangements until the Mutual Defense Agreement of 1958. There were times when the perceived national interests of the two countries were unsynchronized or at odds; periods when political leaders did not see eye to eye or made secret agreements that remained just that; and when espionage, propaganda, and public opinion caused addi- tional tensions. STATUS IMBALANCE The Magna Carta of the nuclear age is the two-part Frisch-Peierls mem- orandum. It was produced by two European émigrés, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, at Birmingham University in the spring of 1940. Un- like Einstein’s famous letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with its vague warning that a powerful new bomb might be constructed from uranium, the Frisch-Peierls memorandum set out detailed technical arguments leading to the conclusion that “a moderate amount of U-235 [highly enriched uranium] would indeed constitute an extremely effi- cient explosive.” Like Einstein, Frisch and Peierls were worried that the Germans might already be working toward an atomic bomb against which there would be no defense. By suggesting “a counter-threat with a similar bomb,” they first enunciated the concept of mutual deterrence and recommended “start[ing] production as soon as possible, even if 36 Historic Barriers to Anglo-American Nuclear Cooperation 37 it is not intended to use the bomb as a means of attack.”1 Professor Mark Oliphant from Birmingham convinced the UK authorities that “the whole thing must be taken rather seriously,”2 and a small group of senior scientists came together as the Maud Committee. -

M-1392 Publication Title: Bush-Conant File

Publication Number: M-1392 Publication Title: Bush-Conant File Relating to the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1940-1945 Date Published: n.d. BUSH-CONANT FILE RELATING TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ATOMIC BOMB, 1940-1945 The Bush-Conant File, reproduced on the 14 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1392, documents the research and development of the atomic bomb from 1940 to 1945. These records were maintained in Dr. James B. Conant's office for himself and Dr. Vannevar Bush. Bush was director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD, 1941-46), chairman of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) prior to the establishment of OSRD (1940-41), chairman of the Military Policy Committee (1942-45) and member of the Interim Committee (May-June 1945). During this period Conant served under Bush as chairman of the National Defense Research Committee of OSRD (1941-46), chairman of the S-1 Executive Committee (1942-43), alternate chairman of the Military Policy Committee (1942-45), scientific advisor to Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves (1943-45), and member of the Interim Committee (May-June 1945). The file, which consists primarily of letters, memorandums, and reports, is part of the Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Record Group (RG) 227. The Bush-Conant File documents OSRD's role in promoting basic scientific research and development on nuclear fission before August 1942. In addition, the files document Bush and Conant's continuing roles, as chairman and alternate chairman of the Military Policy Committee, in overseeing the army's development of the atomic bomb during World War II and, as members of the short-lived Interim Committee, in advising on foreign policy and domestic legislation for the regulation of atomic energy immediately after the war. -

The 2000 Npt Review Conference

THE 2000 NPT REVIEW CONFERENCE CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS TARIQ RAUF Center for Nonproliferation Studies Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………...…..4 NPT BARGAIN………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Nuclear Nonproliferation Concerns…………………………………………………………………………………..5 Nuclear Disarmament Concerns….………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Impediments to Sharing of Civilian Nuclear Technology…………………………………………………………….5 NPT REVIEW………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 THE NUCLEAR NONPROLIFERATION TREATY…………………………………………………………….6 Decision 1: Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty……………………….…………………………….….7 Decision 2: Principles and Objectives for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament…………………………. 10 Decision 3: Extension of the NPT…………………………………………………………………………………….11 The Resolution on the Middle East…………………………………………………………………………………...12 SUBSTANTIVE ISSUES AT THE 2000 NPT REVIEW CONFERENCE……………………………………...13 Non-proliferation (Articles I / II)……………………………………………………………………………………..13 Strengthened IAEA Safeguards (NPT Article III) and Export Controls……………………………………………...15 Cooperation in Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy (NPT Article IV)………………………………………………….17 Peaceful Nuclear Explosions (Article V)……………………………………………………………………………..17 Nuclear Disarmament (Article VI)…………………………………………………………………………………...18 Update on the 1995 Programme of Action…………………………………………………………………………...19 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test Ban Treaty…………………………………………………………………………….19 Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty……………………………………………………………………………………….20 Nuclear Disarmament………………………………………………………………………………………………...21 -

Hiroshima-Nagasaki, Teachings of Peace for Humanity

INSTITUTO DIOCESANO DEL PROFESORADO M. RASPANTI HIROSHIMA-NAGASAKI, TEACHINGS OF PEACE FOR HUMANITY 1. Members of the chair1 Lecturer E-mail Cecilia Onaha [email protected] Nélida Shinzato [email protected], [email protected] Matías Iglesias [email protected] Vicente Haya [email protected] Osvaldo Napoli [email protected] Tomoko Aikawa [email protected] 2. Targets The course is part of the curriculum of the Special Education Teacher Training, Religious Education and Psychopedagogy programs. For our students it will be a compulsory course. It will form the content of the subjects "Field of Practice" and "Tools of the Field of Professional Teaching Practice". It will also be open to professionals and agents of the field of education, social work and social health, as well as students and teachers of related careers, to whom an institutional certificate of the course will be given. 3. Area in which the course is located within the programs The course is in the Culture of Peace course of studies, within the area of Education for Global Citizenship, within the framework of the UNESCO Chair Education for Diversity based in our Institute. 4. Justification of the course In virtue of our UNESCO Chair, we have taken as our own the axis of global citizenship that emerges from the Sustainable Development Goals of the UNESCO 2030 Agenda, in particular, Goal 4.7, which aims to ensure that all students acquire the 1 See last page for a brief resume of the lecturers. 1 theoretical and practical knowledge to promote, among other things, sustainable development, human rights, the promotion of the culture of peace and non-violence, world citizenship and the appreciation of cultural diversity. -

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff Meerut and the Creation of “Official” Communism in India

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East Separating the Wheat from the Chaff Meerut and the Creation of “Official” Communism in India Ali Raza ew events have been as significant for the leftist movement in colonial India as the Meerut Conspir- acy Case. At the time, the case captured the imagination of virtually all political sections in British India as well as left- leaning organizations around the globe. It also defined the way in which the FLeft viewed itself and conducted its politics. Since then, the case has continued to attract the attention of historians working on the Indian Left. Indeed, it is difficult to come across any work on the Left that does not accord a prominent place to Meerut. Despite this, the case has been viewed mostly in terms that tend to diminish its larger significance. For one, within the rather substantial body of literature devoted to the Indian Left, there have been very few works that examine the case with any degree of depth. Most of those have been authored by the Left itself or by political activists who were defendants in the case. Whether authored by the Left or by academ- ics, the literature generally contends that the Raj failed in its objective to administer a fatal blow to “com- munism” in India. Instead, it’s commonly thought that the trial actually provided a fillip to communist politics in India.1 Not only did the courtroom provide an unprecedented opportunity to the accused to openly articulate their political beliefs, but it also generated public sympathy for communism. -

Anglo-Soviet Relations, 1927-1932

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Anglo-Soviet relations, 1927-1932. Bridges, Brian J. E How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Bridges, Brian J. E (1979) Anglo-Soviet relations, 1927-1932.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43078 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ ANGLO-SOVIET RELATIONS 1927 - 1932 by BRIAN J. E. BRIDGES Ph.D. University College April, 1979 of Swansea ProQuest Number: 10821470 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Physics, Physicists and the Bomb

editorial Physics, physicists and the bomb Scientists involved in nuclear research before and after the end of the Second World War continue to be the subjects of historical and cultural fascination. Almost 70 years since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the military, historical and moral implications of the nuclear bomb remain firmly lodged in the public’s consciousness. Images of mushroom clouds serve as powerful reminders of the destructive capability that countries armed with nuclear weapons have access to — a capability that continues to play a primary role in shaping the present geopolitical landscape of the world. For physicists, the development of the nuclear bomb generally brings up conflicting feelings. On the one hand, physicists played a central role in helping to create it; on the SCIENCE SOURCE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY PHOTO SOURCE/SCIENCE SCIENCE other, they were also among the first to realize © its terrifying power. This contradiction is most Manhattan Project physicists at Los Alamos. From left to right: Kenneth Bainbridge, Joseph Hoffman, famously epitomized by Robert Oppenheimer, Robert Oppenheimer, Louis Hempelmann, Robert Bacher, Victor Weisskopf and Richard Dodson. the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, who, on witnessing the first test of the atomic bomb, the Trinity test, in July 1945, in this context that the public can truly come race following the Second World War, there was reminded of a quote from the Hindu to feel the growing sense of disillusionment is no question that Churchill was an early scripture Bhagavad Gita: “Now, I am become of those scientists as they realized their goal; and influential champion for government- Death, the destroyer of worlds.” a sense of lost innocence, that knowledge that sponsored science and technology in Britain.