Conceiving Iran's Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Read the Introduction

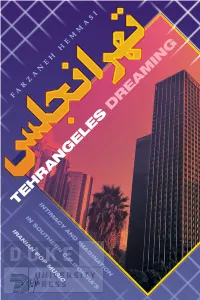

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström

Online version of Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström Stockholm, Svenskt visarkiv, 2003 Publications issued by Svenskt visarkiv 18 Translated by Kristina Radford & Andrew Coultard Illustrations: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist For additional material, go to http://old.visarkiv.se/online/online_mmm.html Contents Preface.................................................................................................. 9 AIMS, THEMES AND TERMS Aims, emes and Terms...................................................................... 13 Music as Objective and Means— Expression and Cause, · Assumptions and Questions, e Production of Difference ............................................................... 20 Class and Ethnicity, · From Similarity to Difference, · Expressive Forms and Aesthet- icisation, Visibility .............................................................................................. 27 Cultural Brand-naming, · Representative Symbols, Diversity and Multiculture ................................................................... 33 A Tradition of Liberal ought, · e Anthropological Concept of Culture and Post- modern Politics of Identity, · Confusion, Individuals, Groupings, Institutions ..................................................... 44 Individuals, · Groupings, · Institutions, Doers, Knowers, Makers ...................................................................... 50 Arenas ................................................................................................. -

2009 Mcnair Scholars Journal

The McNair Scholars Journal of the University of Washington Volume VIII Spring 2009 THE MCNAIR SCHOLARS JOURNAL UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON McNair Program Office of Minority Affairs University of Washington 375 Schmitz Hall Box 355845 Seattle, WA 98195-5845 [email protected] http://depts.washington.edu/uwmcnair The Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program operates as a part of TRIO Programs, which are funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Cover Art by Jeff Garber www.jeffgarberphoto.com University of Washington McNair Program Staff Program Director Gabriel Gallardo, Ph.D. Associate Director Gene Kim, Ph.D. Program Coordinator Rosa Ramirez Graduate Student Advisors Audra Gray Teresa Mares Ashley McClure Hoang Ngo McNair Scholars‘ Research Mentors Dr. Rick Bonus, Department of American Ethnic Studies Dr. Sarah Bryant-Bertail, Department of Drama Dr. Tony Gill, Department of Political Science Dr. Doug Jackson, Department of Oral Medicine Dr. Bryan D. Jones, U.W. Center of Politics and Public Policy Dr. Ralina Joseph, Department of Communications Dr. Elham Kazemi, Department of Education Dr. Neal Lesh, Department of Computer Engineering Dr. Firoozeh Papan-Matin, Persian and Iranian Studies Program Dr. Dian Million, American Indian Studies Program Dr. Aseem Prakas, Department of Political Science Dr. Kristin Swanson, Department of Pathology Dr. Ed Taylor, Dean of Undergraduate Academic Affair/ Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Dr. Susan H. Whiting, Department of Political Science Dr. Shirley Yee, Department of Comparative History of Ideas Volume VIII Copyright 2009 ii From the Vice President and Vice Provost for Diversity One of the great delights of higher education is that it provides young scholars an opportunity to pursue research in a field that interests and engages them. -

Download (1MB)

Trends in Contemporary Conscious Music in Iran Dr Malihe Maghazei LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series / 03 June 2014 Trends in Contemporary Conscious Music in Iran The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) or the Middle East Centre. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s) and the LSE Middle East Centre should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material in this paper, the author(s) and/or the LSE Middle East Centre will not be liable for any loss or damages incurred through the use of this paper. 2 Trends in Contemporary Conscious Music in Iran About the Author Originally from Iran, Dr Malihe Maghazei joined the LSE Middle East Centre as a Visiting Fellow in October 2012. She is a social historian of the Middle East who specialises in the contemporary history of Iran. She has taught history courses including World Civilization since the 16th century at California State University, Fullerton and Women in the Middle East at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research interests include gender and Islam, youth, culture, and intellectual movements in Iran. Dr Maghazei has researched various topics in both Persian and English including the dominant discourse of orientalism on Muslim women, the feminist movement in Iran and Iranian youth. Her publications include: ‘The Account of Creation in the Holy Scriptures: A Comparative Study between the Bible and the Qur’an’, Humanity, Tehran, 2010; ‘Islamic Feminism: Periphery or Growing Trend’, Groningen University, Centre for Gender Studies, 2012; and ‘Teens’ Life in Iran’ in Teen’s Life in the Middle East, Greenwood Press, 2003. -

Migration and Music Music.” Music Research Annual 1: 1–24

Stokes, Martin. 2020. “Migration and Migration and Music Music.” Music Research Annual 1: 1–24. martin stokes ABSTRACT: The current sense of crisis in the study of migration and music calls out for a broader contextualization. The study of migrant culture sat comfortably for a while with a structural-functionalist culture concept emphasizing boundedness and stasis, figured astransitional , adaptive, evidence of modernization or Westernization. An orientation toward hybridity in the 1980s began to shake some of these certainties, even if it kept others (the normative framework of the nation-state) in place. This article argues that work on refugees and diasporas at around the same time departed from them more radically. The current moment is one in which the final vestiges of language about migrant culture as adaptive have been swept away and in which the populist evocation of a migrant crisis at our gates has posed unsettling challenges. This article explores the tensions in the current literature between an emphasis on migrant creativity and survival, mobility and motility, and identity and citizenship. KEYWORDS: music, dance, migration, refugees, mobility, citizenship MARTIN STOKES is King Edward Professor of Music at King’s College London. Marked as it is by a sense of crisis, the field of music and migration has become “impossible to map,” as one recent commentator observes (Aksoy 2019, 299). The measured language of the social sciences and the humani- ties—contextualizing, explaining, interpreting—does not fit easily with the emotions many of us surely feel at the news that flashes across our screens. Another boat laden with migrants sinks. -

Traditional Iranian Music in Irangeles: an Ethnographic Study in Southern California

Traditional Iranian Music in Irangeles: An Ethnographic Study in Southern California Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Yaghoubi, Isra Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 05:58:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/305864 TRADITIONAL IRANIAN MUSIC IN IRANGELES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA by Isra Yaghoubi ____________________________ Copyright © Isra Yaghoubi 2013 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2013 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Isra Yaghoubi APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved -

Conceiving Iran's Future

1 CONCEIVING IRAN’S FUTURE: YOUTH AND THE TRANSITION TO PARENTHOOD MEHRNOUSH SHAFIEI INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC STUDIES MCGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL JUNE, 2011 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts—Thesis © Mehrnoush Shafiei 2 For my mother . 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................3 ABSTRACT/ABSTRAIT...............................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………............6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION………………………………….........7 CHAPTER TWO: THE NATION................................................................23 CHAPTER THREE: SACRIFICE................................................................55 CHAPTER FOUR: RESPONSIBILITY.......................................................84 CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION.............................................................109 WORKS CONSULTED…………………………………………………..117 4 ABSTRACT Since the publication of images of Iranian students’ raised angry fists storming the American embassy in 1979, the idea of Iranian youth has captured the world’s imagination and has been a source of puzzlement. The children of the Iranian revolution are today old enough to have their own children. Thus, one unique and original window from which to study Iranian youth is to investigate as they undergo the significant transition from youth to parenthood. This study will be in conversation with three expecting Montreal-based -

From Music Ontology Towards Ethno-Music-Ontology

FROM MUSIC ONTOLOGY TOWARDS ETHNO-MUSIC-ONTOLOGY Polina Proutskova1 Anja Volk2 Peyman Heidarian3 György Fazekas1 1 Center for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London, UK 2 Department of Information and Computing Sciences, Utrecht University, Netherlands 3 Department of Computer Science The University of Waikato, NZ [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT sual knowledge about the entities and their relationships in an area, preferably expressed using a machine-processable This paper presents exploratory work investigating the formal language that supports some form of inference [12]. suitability of the Music Ontology [33] - the most widely This could be logic based, while more recently, ontologies used formal specification of the music domain - for mod- found their use in machine learning as a mechanism to help elling non-Western musical traditions. Four contrasting structuring training data, formalise constraints, or become case studies from a variety of musical cultures are anal- an integral part of the inference process [42]. ysed: Dutch folk song research, reconstructive perfor- The Music Ontology (MO) [32, 33] is among the most mance of rural Russian traditions, contemporary perfor- comprehensive ontologies for the music domain, with mance and composition of Persian classical music, and broad ranging applications [9, 38] from recommendation recreational use of a personal world music collection. We systems [49] to live performance [51], and numerous ex- propose semantic models describing the respective do- tensions covering music production [10, 11] and audio ef- mains and examine the applications of the Music Ontology fects [53, 54], audio features [1], music theoretical con- for these case studies: which concepts can be successfully cepts [34, 43, 46], smart instruments and more generic or reused, where they need adjustments, and which parts of other “Musical Things” [48]. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA SUMMER TABESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2009 G SUMMER/JUNE 2009 Tir – AmordadJOURJO – Shehrever 1378 AY (Fasli) G Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY, Fravardin 1379 AY (Shenshai) N G Spendarmad 1378AL AY, Fravardin – Ardibehesht 1379 AY (Kadimi) Chicago area Zarathushtis celebrate the arrival of the Spring Equinox in a special sunrise ceremony at the lakefront planetarium Also Inside: Pakistan Revisited Passport to Persia Festival ZAPANJ at the Philadelphia Museum Navroze Celebrations Across North America PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 2 Summer / Tabestan 1378 AY 3747 ZRE President Bomi Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel 5 Financial Report Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 7 Coming Events [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, 9 NOROOZ -Celebrations Around www.khanizadeh.info the World Cover design: Feroza Fitch, [email protected] 23 JUNGALWALLA LECTURE Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 65 NOROOZ Photo Montage Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : 74 PAKISTAN REVISITED [email protected] Yezdi Godiwala [email protected] 95 Mumbai’s Last Parsi Restaurants Fereshteh Khatibi: [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 99 A Secret Place: San Jose Darbe Mahrukh -

053777/Sem Newsletter

SEM Newsletter Published by the Society for Ethnomusicology Volume 37 • Number 4 • September 2003 SEM Soundbyte “Body Special Events at Mi- Judith O. Becker, Meets the Bored” ami 2003 SEM, CMS, Seeger Lecturer 2003 By Ellen Koskoff, SEM President ATMI Joint Meeting By Deborah Wong, Secretary, SEM Board of Directors OK, let’s face it—over the past few By Alan Burdette and the Local years, our annual meeting/mating ritual, Arrangements Committee Judith O. Becker will present the Body Meets the Board, where the Board th The 2003 Annual Meeting of the Seeger lecture at the 48 annual SEM and the general membership come to- Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM) will meeting in Miami. Her presentation, gether (usually over a dinner hour) to be heldBiscayne jointly, October Bay, 2-5,Miami with The titled “Trancers and Deep Listeners,” ask questions, raise issues, and air prob- College Music Society (CMS) and the will be taken from her forthcoming lems, has not been working. Finding an Association for Technology in Music book, Deep Listeners: Music, Emotion audience has been getting harder and Instruction (ATMI), and it promises to and Trancing (Indiana University Press, harder. Occasionally, to provide a quo- be an unforgettable gathering of minds in press). rum, people have been rounded up at Prof. Becker is especially known for and music. In addition, the participants the last minute as ringers . Last year, her scholarship on the musics of South- will enjoy the luxurious Inter-Continen- at Estes Park, only two people showed east Asia, particularly the gamelan mu- tal Hotel on the coast of Biscayne Bay in up (and even one Board member was sic of Central Java.