The Performing and Teaching Practices of Iranian Musicians in Canada: Influences of a Multicultural Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

A Musical Instrument of Global Sounding Saadat Abdullayeva Doctor of Arts, Professor

Focusing on Azerbaijan A musical instrument of global sounding Saadat ABDULLAYEVA Doctor of Arts, Professor THE TAR IS PRObabLY THE MOST POPULAR MUSICAL INSTRUMENT AMONG “The trio”, 2005, Zakir Ahmadov, AZERbaIJANIS. ITS SHAPE, WHICH IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER STRINGED INSTRU- bronze, 40x25x15 cm MENTS, IMMEDIATELY ATTRACTS ATTENTION. The juicy and colorful sounds to the lineup of mughams, and of a coming from the strings of the tar bass string that is used only for per- please the ear and captivate people. forming them. The wide range, lively It is certainly explained by the perfec- sounds, melodiousness, special reg- tion of the construction, specifically isters, the possibility of performing the presence of twisted steel and polyphonic chords, virtuoso passag- copper strings that convey all nuanc- es, lengthy dynamic sound rises and es of popular tunes and especially, attenuations, colorful decorations mughams. This is graphically proved and gradations of shades all allow by the presence on the instrument’s the tar to be used as a solo, accom- neck of five frets that correspondent panying, ensemble and orchestra 46 www.irs-az.com instrument. But nonetheless, the tar sounding board instead of a leather is a recognized instrument of solo sounding board contradict this con- mughams when the performer’s clusion. The double body and the mastery and the technical capa- leather sounding board are typical of bilities of the instrument manifest the geychek which, unlike the tar, has themselves in full. The tar conveys a short neck and a head folded back- the feelings, mood and dreams of a wards. Moreover, a bow is used play person especially vividly and fully dis- this instrument. -

"Tal-Grixti" a Family of Żaqq and Tanbur Musicians

"TAL-GRIXTI" A FAMILY OF ŻAQQ AND TANBUR MUSICIANS Anna Borg Cardona, B.A., L.T.C.L. On his visit to Malta, George Percy Badger (1838) observed that Unative musical instruments", were "getting into disuse" (1). Amongst these was the Maltese bagpipe known as żaqq'. A hundred years later, the żaqq was stil1 in use, but evidently still considered to be waning. By the end of the first half of the twentieth century, the few remaining żaqq musicians were scattered around the isla:nd of Ma1ta in Naxxar, Mosta, Siġġiewi, Dingli, Żurrieq, Birgu (Vittoriosa), Marsa, Mellieħ.a and also on the sister island of Gozo, in Rabat. By the time Partridge and Jeal (2) investigated the situation between 1971 and 1973, they found a total of9living players in Malta and none in Gozo. Now the instrument is no longer played and may be considered virtually extinct. Zaqq players up to the early part of the twentieth century used to perform in the streets and in coffee or wine bars. They would often venture forth to nearby villages, making melodious music to the accompaniment of percussive instruments such as tambourine (tanbur) or fiiction drum (rabbaba, żuvżaJa). It was also not uncommon to witness a group of dancers c10sely followingthe musicians and contorting to their rhythms. This music came to be expected especially a.round Christmas time, Feast days (Festi) and Camival time. The few musicians known as żaqq players tended to pass theit knowledge on from generation to generation, in the same way as other arts, crafts and trades were handed down. -

Newsletter Spring 2006 FINAL!.Indd

CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 18, No. 1 SIPA-Columbia University-New York Spring 2006 ENCYCLOPÆDIA IRANICA GALA BENEFIT FASCICLE 3 OF VOLUME XIII PUBLISHED, DINNER FASCICLE 4 IN PRESS SAN FRANCISCO AY In 2005, the Encyclopædia ing this goal are by no means M 13, 2006 Iranica arrived at an important minimized. Such complexities juncture, one might say a milestone, become the main focus of the final when it reached the entry IRAN. sub-article. It had long been felt that although The Series consists of the fol- the entire Encyclopædia is about lowing entries: i. LANDS OF IRAN Iran, yet we needed a series of articles (a geographical essay), ii. FACTUAL under that general rubric to provide an HISTORY OF IRAN, iii. TRADITIONAL HIS- overview of the main facets of Iranian TORY OF IRAN, iv. IRANIAN MYTHS AND geography, history, and culture. This LEGENDS, v. PEOPLES OF IRAN, vi. IRANIAN series of entries began in Fascicle 2 of LANGUAGES AND SCRIPTS, vii. NON-IRA- Volume XIII, continues through Fas- NIAN LANGUAGES IN IRAN, viii. PERSIAN cicles 3 and 4, and will take most of LITERATURE, ix. RELIGION IN IRAN, x. Fascicle 5 to complete. PERSIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE, xi. Maryam Rahimian The details of the topics discussed PERSIAN MUSIC, xii. HISTORY OF SCIENCE in these articles will be covered by other IN IRAN, xiii. PERSIA AND THE WEST, xiv. entries throughout the Encyclopædia. IRANIAN IDENTITY. The elegant Ritz Carlton Hotel in Here the purpose has been to present Within many of the above, the San Francisco will be the venue of a a concise general account of what a discussion is further subdivided by Gala Benefit Dinner for the Encyclopæ- student of the Iranian world and its time period—at least into those of pre- dia Iranica on May 13, 2006. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

Amunowruz-Magazine-No1-Sep2018

AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE | NO. 1 | SEPTEMBER 2018 27SEP. HAPPY WORLD TOURISM DAY Taste Persia! One of the world's most ancient and important culinary schools belongs to Iran People of the world; Iran! Includes 22 historical sites and a natural one. They 're just one small portion from Iran's historical and natural resources Autumn, one name and a thousand significations About Persia • History [1] Contents AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE | NO. 1 | SEPTEMBER 2018 27SEP. HAPPY WORLD TOURISM DAY Taste Persia! One of the world's most ancient and important culinary schools belongs to Iran Editorial 06 People of the world; Iran! Includes 22 historical sites and a natural one. They 're just one small portion from Iran's historical and natural resources Autumn, one name and a thousand significations Tourism and the Digital Transformation 08 AMU NOWRUZ E-MAGAZINE NO.1 SEPTEMBER 2018 10 About Persia History 10 A History that Builds Civilization Editorial Department Farshid Karimi, Ramin Nouri, Samira Mohebali UNESCO Heritages Editor In Chief Samira Mohebali 14 People of the world; Iran! Authors Kimia Ajayebi, Katherin Azami, Elnaz Darvishi, Fereshteh Derakhshesh, Elham Fazeli, Parto Hasanizadeh, Maryam Hesaraki, Saba Karkheiran, Art & Culture Arvin Moazenzadeh, Homeira Mohebali, Bashir Momeni, Shirin Najvan 22 Tourism with Ethnic Groups in Iran Editor Shekufe Ranjbar 26 Religions in Iran 28 Farsi; a Language Rooted in History Translation Group Shekufe Ranjbar, Somayeh Shirizadeh 30 Taste Persia! Photographers Hessam Mirrahimi, Saeid Zohari, Reza Nouri, Payam Moein, -

The Poetics of Persian Music

The Poetics of Persian Music: The Intimate Correlation between Prosody and Persian Classical Music by Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie B.A., The University of Toronto, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie, 2010 Abstract Throughout most historical narratives and descriptions of Persian arts, poetry has had a profound influence on the development and preservation of Persian classical music, in particularly after the emergence of Islam in Iran. A Persian poetic structure consists of two parts: the form (its fundamental rhythmic structure, or prosody) and the content (the message that a poem conveys to its audience, or theme). As the practice of using rhythmic cycles—once prominent in Iran— deteriorated, prosody took its place as the source of rhythmic organization and inspiration. The recognition and reliance on poetry was especially evident amongst Iranian musicians, who by the time of Islamic rule had been banished from the public sphere due to the sinful socio-religious outlook placed on music. As the musicians’ dependency on prosody steadily grew stronger, poetry became the preserver, and, to a great extent, the foundation of Persian music’s oral tradition. While poetry has always been a significant part of any performance of Iranian classical music, little attention has been paid to the vitality of Persian/Arabic prosody as its main rhythmic basis. Poetic prosody is the rhythmic foundation of the Persian repertoire the radif, and as such it makes possible the development, memorization, expansion, and creation of the complex rhythmic and melodic compositions during the art of improvisation. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Blogging Iran – a Case Study of Iranian English Language Weblogs

UNIVERSITY OF OSLO FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES TIK Centre for technology, innovation and culture P.O. BOX 1108 Blindern N-0317 OSLO Norway http://www.tik.uio.no ESST The European Inter-University Association on Society, Science and Technology http://www.esst.uio.no The ESST MA Blogging Iran – A Case Study of Iranian English Language Weblogs Peder Are Nøstvold Jensen University of Oslo Nature and Culture 2004 24.819 Words 1 Supervisor for this Master thesis has been Professor Terje Rasmussen from the Department of Media and Communication, the University of Oslo, Norway. I would also like to thank Elisabeth Staksrud from Statens Filmtilsyn for valuable information, and for pointing me to the Nordic Institute for Asian Studies (NIAS) in Copenhagen, Denmark, who were kind enough to offer me a scholarship and the opportunity to use their library. James Gomez was generous enough to send me his excellent new book Asian Cyberactivism for free. Last, but not least, I have to thank Mr. Hossein Derakhshan for spending some of his time giving me information and granting me an interview. Without him, and the other Iranian webloggers described here, this Master thesis would not have been possible. 2 Chapter outline of thesis: 1 Motivation 2. Methodology 3. The Internet and censorship 4. Background on Internet censorship in several countries 4.1 The case of China 4.2 The case of Singapore 4.3 Burma 5. The situation in Iran – Politics and censorship 6. Weblogs 6.1 About weblogs 6.2 Iranian weblogs 6.3 About description of weblogs 7. Weblogs – case studies 7.1 Weblogs by Insiders, Iranians in Iran 7.1.1 Additional weblogs by Insiders 7.2 Weblogs by Outsiders, Iranians in exile 7.3 Summary, and conclusion about weblog findings 8. -

Read the Introduction

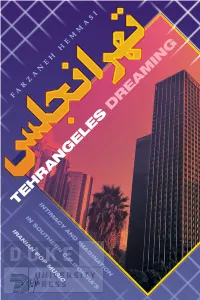

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Data Collection Survey on Tourism and Cultural Heritage in the Islamic Republic of Iran Final Report

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN IRANIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE, HANDICRAFTS AND TOURISM ORGANIZATION (ICHTO) DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON TOURISM AND CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) HOKKAIDO UNIVERSITY JTB CORPORATE SALES INC. INGÉROSEC CORPORATION RECS INTERNATIONAL INC. 7R JR 18-006 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON TOURISM AND CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ v Maps ........................................................................................................................................ vi Photos (The 1st Field Survey) ................................................................................................. vii Photos (The 2nd Field Survey) ............................................................................................... viii Photos (The 3rd Field Survey) .................................................................................................. ix List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................ x 1. Outline of the Survey ....................................................................................................... 1 (1) Background and Objectives .....................................................................................