Download (1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamal Rostami

CURRICULUM VITAE JAFAR KHADEMI HAMIDI, Ph.D. Mining Eng. Dept., Faculty of Engineering Phone: +98 21-82884364 Tarbiat Modares University Fax: +98 21-82884324 Jalal Ale Ahmad Highway, Nasr Bridge Email: [email protected] P.O. Box: 14115-143, Tehran, Iran http://www.modares.ac.ir/~jafarkhademi SUMMARY OF EXPERIENCE Jafar Khademi Hamidi received his PhD degree in Mining Engineering from Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic) in January 2011 with dissertation entitled "A model for hard rock TBM performance prediction". As a PhD student in Tehran Polytechnic, he was a recipient of several competitive awards that include honored and top-rank recognition student, selected young researcher, sabbatical opportunity and INEF awards. He worked as a consultant in the area of underground construction, mechanical excavation, geotechnical investigations, construction bid preparation, tunneling in difficult ground conditions and longwall coal mine design between 2006 and 2013. He has started faculty job at Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) from spring 2012. Currently, as an Assistant Professor of Mining Engineering and founder of Mechanized Excavation Laboratory in TMU, he is to pursue basic and applied researches in the field of mechanical mining and excavation. RESEARCH INTEREST Underground mining (geotechnical engineering, design and planning, risk analysis) Mechanical mining and excavation (rock drillability/cuttability/boreability, design and fabrication of rock cuttability index tests, rock abrasion and tool wear) GIS -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Social and Cultural Context Affecting the Activities of Women Painters of Pahlavi Era (1925-1978)

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 9, No. 3; 2016 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Social and Cultural Context Affecting the Activities of Women Painters of Pahlavi Era (1925-1978) Azadeh Alipoor Heris1 & Abolghasem Dadvar1 1Art Faculty, Azzahra University, Tehran, Iran Correspondence: Azadeh Alipoor Heris, Art Faculty, Azzahra University, Tehran, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 23, 2015 Accepted: April 2, 2016 Online Published: April 27, 2016 doi:10.5539/jpl.v9n3p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v9n3p1 Abstract Different factors were affecting the presence of women during the Pahlavi era. In new structures after the constitutional period and along with the absolute modernism of Pahlavi, discourses changes were made based on democracy, socialism, Shia resistance and autonomy, court to government and political figures to people. During this period the role of women was formed on the basis of their social position and in their gender approach it changed from a <class in itself> to a <class for self>. The consequences of social contexts led to witness more active presence of women during Pahlavi era compared with the past periods particularly in the visual arts arena; so that the history of the Tehran galleries from 1953-1978 which reflects their activities during that time confirms this fact. The purpose of the present essay is to analyze the social contexts which have attracted women from margin to the center and attending to them since no study -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

Tehran in Hook

Tehran in hook Tehrani “underground” musicians “keeping it real” Tiina Valjanen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Social and Cultural Anthropology Master's thesis May 2021 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildingsprogram – Degree Programme Faculty of Social Sciences Master's Programme in Contemporary Societies (COS) Tekijä – Författare – Author Tiina Valjanen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Tehran in hook: Tehrani “underground” musicians “keeping it real” Oppiaine/Opintosuunta – Läroämne/Studieinriktning – Subject/Study track Social and Cultural Anthropology Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages Master's thesis May 2021 107 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract This thesis is an ethnographic study about rap, rock, and metal scenes in today’s Tehran. The study takes off from hip-hop scholars Pennycook’s and Mitchell’s proposition of hip-hop as “dusty foot philosophy” which is rooted at local dusty ground while articulating philosophies of global significance. This study aims to examine what kind of spaces are these dusty streets in Tehran and how does Tehran’s urban landscape inform music making and music aesthetics. This study focuses on how notions of belonging, space, and place have been expressed by rappers and rockers both in their music making and their embodied use of urban spaces. Followingly it will observe how urban realities, urban space, and geographical segregation are perceived, challenged, and reclaimed through their craft. The study asks how underground musicians are debating questions of authenticity that have risen along music’s localization, and how musicians strive for artistic legitimacy which would verify their street credibility both within their local music scenes and wider society, as well as within global music community. -

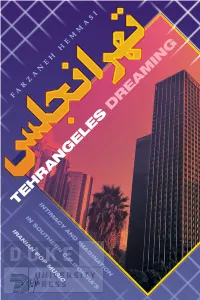

Read the Introduction

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Consumer Lifestyles in Iran

CONSUMER LIFESTYLES IN IRAN Euromonitor International November 2016 CONSUMER LIFESTYLES I N I R A N P a s s p o r t I LIST OF CONTENTS AND TABLES Lifestyles in Iran ........................................................................................................................... 1 Chart 1 Lifestyles in Iran ........................................................................................... 1 Top Five Consumer Trends .......................................................................................................... 1 Pent-up Consumers Eager for Post-accord Shopping Benefits ................................................ 1 Social Changes Have Defined Behaviour of Young Consumers .............................................. 2 Consumers Flock To New Shopping Malls ............................................................................... 3 Online Shopping on the Rise .................................................................................................... 3 Sophisticated Consumers Drive Demand for Luxury Products ................................................. 4 Consumer Segmentation .............................................................................................................. 4 Babies and Infants .................................................................................................................... 4 Chart 2 Babies and Infants in Focus 2000-2020 ....................................................... 6 Kids .......................................................................................................................................... -

Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström

Online version of Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström Stockholm, Svenskt visarkiv, 2003 Publications issued by Svenskt visarkiv 18 Translated by Kristina Radford & Andrew Coultard Illustrations: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist For additional material, go to http://old.visarkiv.se/online/online_mmm.html Contents Preface.................................................................................................. 9 AIMS, THEMES AND TERMS Aims, emes and Terms...................................................................... 13 Music as Objective and Means— Expression and Cause, · Assumptions and Questions, e Production of Difference ............................................................... 20 Class and Ethnicity, · From Similarity to Difference, · Expressive Forms and Aesthet- icisation, Visibility .............................................................................................. 27 Cultural Brand-naming, · Representative Symbols, Diversity and Multiculture ................................................................... 33 A Tradition of Liberal ought, · e Anthropological Concept of Culture and Post- modern Politics of Identity, · Confusion, Individuals, Groupings, Institutions ..................................................... 44 Individuals, · Groupings, · Institutions, Doers, Knowers, Makers ...................................................................... 50 Arenas ................................................................................................. -

Pegah Ahmadi Was Born in Tehran in 1974. She Is

Pegah Ahmadi was born in Tehran in 1974. She is the author of three volumes of poetry, On the Ending G, Cadence, and These Days of Mine Are A Throat, an interweaving of modern Farsi and ancient Persian, in which she explores the history of cruelty against women in Iran, criticizing the Islamic religion and its influence on Iran’s social-political situation, published in 2002. That same year, she also published a translation of poetry by Sylvia Plath entitled Mad Girl’s Love Song, and collected, edited, introduced and published an anthology gathering the work of Iranian women poets, both historical and contemporary. Shortly after, she was banned from publishing poetry in her home country, except, in a limited manner, through online venues run by exiled Iranian writers. In 2009, following her involvement in the Green Movement’s demonstrations against Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, she was threatened with imprisonment, and left Iran with the assistance of the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN), which placed her as a guest writer in the city-of-refuge site in Frankfurt, Germany. During her years in Frankfurt her long unpublished book, I Was Not Cold, translated into German by Jutta Himmelreich, was published by Sujet Verlag in Berlin. Ahmadi is in residence at Brown for the 2011-12 academic year. Born in Tehran in 1938, Bahram Beyzaie is a well known Iranian critic, researcher, teacher, playwright, stage director (and producer), screenwriter and filmmaker (director, producer and editor) who has written more than 35 plays and more than 50 screenplays, including feature films Downpour, The Stranger and The Fog, The Crowd, Death of Yazdgerd, and Bashu, the Little Stranger. -

2009 Mcnair Scholars Journal

The McNair Scholars Journal of the University of Washington Volume VIII Spring 2009 THE MCNAIR SCHOLARS JOURNAL UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON McNair Program Office of Minority Affairs University of Washington 375 Schmitz Hall Box 355845 Seattle, WA 98195-5845 [email protected] http://depts.washington.edu/uwmcnair The Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program operates as a part of TRIO Programs, which are funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Cover Art by Jeff Garber www.jeffgarberphoto.com University of Washington McNair Program Staff Program Director Gabriel Gallardo, Ph.D. Associate Director Gene Kim, Ph.D. Program Coordinator Rosa Ramirez Graduate Student Advisors Audra Gray Teresa Mares Ashley McClure Hoang Ngo McNair Scholars‘ Research Mentors Dr. Rick Bonus, Department of American Ethnic Studies Dr. Sarah Bryant-Bertail, Department of Drama Dr. Tony Gill, Department of Political Science Dr. Doug Jackson, Department of Oral Medicine Dr. Bryan D. Jones, U.W. Center of Politics and Public Policy Dr. Ralina Joseph, Department of Communications Dr. Elham Kazemi, Department of Education Dr. Neal Lesh, Department of Computer Engineering Dr. Firoozeh Papan-Matin, Persian and Iranian Studies Program Dr. Dian Million, American Indian Studies Program Dr. Aseem Prakas, Department of Political Science Dr. Kristin Swanson, Department of Pathology Dr. Ed Taylor, Dean of Undergraduate Academic Affair/ Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Dr. Susan H. Whiting, Department of Political Science Dr. Shirley Yee, Department of Comparative History of Ideas Volume VIII Copyright 2009 ii From the Vice President and Vice Provost for Diversity One of the great delights of higher education is that it provides young scholars an opportunity to pursue research in a field that interests and engages them. -

Introduction to Persian Traditional Music

1/9/14 Beyond the Veil: Persian Traditional Music http://www.internews.org/visavis/BTVPagesInews/Persian_trad_music.html Go NOV JAN FEB 110 captures 14 3 Feb 99 ‑ 11 Oct 13 2007 2008 2009 IN THIS SECTION | The Iranian Cinema | Literature| Persian Traditional Music Introduction to Persian Traditional Music by SHAHROKH YADEGARI IN THIS ARTICLE The Influence of Islam The Marriage of Melody with Poetry Radif the foundation of skilled improvisation Popularization and return to roots After the 1979 Revolution Links and recommended recordings The music of Iran has changed considerably in the past 25 years, which incidentally is the period of the Islamic Revolution and the establishment of theocracy in Iran. It is an open question whether Iranian music has changed as a direct result of the Revolution, or whether the music would have evolved similarly in any case. Before 1979, one could easily have separated Persian music into two distinct categories: art music and pop music. The strong censorship practiced before the Revolution required the music to be void of any political messages, and most of the time pop music was the form presented on The National Radio and Television of Iran. Broadcasts of traditional music performances usually ran no longer than 15 minutes. This restriction was established by the producers and had the effect of cramping the music and its form. One can compare traditional Persian music to the classical music of the West, which one should listen to from the beginning to the end with full attention. This form of Iranian music is based on improvisation and has a very inward quality.