University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wir Sind Die Medien

Marcus Michaelsen Wir sind die Medien Kultur und soziale Praxis Marcus Michaelsen (Dr. phil.) promovierte in Medien- und Kommunikations- wissenschaft an der Universität Erfurt. Seine Forschungsschwerpunkte sind digitale Medien, Demokratisierung sowie die Politik und Gesellschaft Irans. Marcus Michaelsen Wir sind die Medien Internet und politischer Wandel in Iran Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution-NonCom- mercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Lizenz (BY-NC-ND). Diese Lizenz erlaubt die private Nutzung, gestattet aber keine Bearbeitung und keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de/. Um Genehmigungen für Adaptionen, Übersetzungen, Derivate oder Wieder- verwendung zu kommerziellen Zwecken einzuholen, wenden Sie sich bitte an [email protected] © 2013 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Die Verwertung der Texte und Bilder ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages ur- heberrechtswidrig und strafbar. Das gilt auch für Vervielfältigungen, Über- setzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und für die Verarbeitung mit elektronischen Systemen. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagkonzept: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Zohreh Soleimani Lektorat & Satz: Marcus Michaelsen Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2311-6 -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Jamal Rostami

CURRICULUM VITAE JAFAR KHADEMI HAMIDI, Ph.D. Mining Eng. Dept., Faculty of Engineering Phone: +98 21-82884364 Tarbiat Modares University Fax: +98 21-82884324 Jalal Ale Ahmad Highway, Nasr Bridge Email: [email protected] P.O. Box: 14115-143, Tehran, Iran http://www.modares.ac.ir/~jafarkhademi SUMMARY OF EXPERIENCE Jafar Khademi Hamidi received his PhD degree in Mining Engineering from Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic) in January 2011 with dissertation entitled "A model for hard rock TBM performance prediction". As a PhD student in Tehran Polytechnic, he was a recipient of several competitive awards that include honored and top-rank recognition student, selected young researcher, sabbatical opportunity and INEF awards. He worked as a consultant in the area of underground construction, mechanical excavation, geotechnical investigations, construction bid preparation, tunneling in difficult ground conditions and longwall coal mine design between 2006 and 2013. He has started faculty job at Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) from spring 2012. Currently, as an Assistant Professor of Mining Engineering and founder of Mechanized Excavation Laboratory in TMU, he is to pursue basic and applied researches in the field of mechanical mining and excavation. RESEARCH INTEREST Underground mining (geotechnical engineering, design and planning, risk analysis) Mechanical mining and excavation (rock drillability/cuttability/boreability, design and fabrication of rock cuttability index tests, rock abrasion and tool wear) GIS -

Turtles Can Fly Won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival

Alice Hsu Agatha Pai Debby Lin Ellen Hsiao Jocelyn Lin Shirley Fang Tony Huang Xray Du Outline Introduction to the Director --Agatha Historical Background of the film –Ellen Main Argument Themes (4) The Mysterious Center (Debby), (1) Ironies (Tony), (2) US Invasion (Shirley) (3) Survival= Fly (Jocelyn) (5) Agrin Questions Agatha Pai Director Bahman Ghobadi ▸ Born on February 1, 1969 (age 42) in Baneh, Kurdistan Province. ▸ Receive a Bachelor of Arts in film directing from Iran Broadcasting College. ▸ Turtles Can Fly won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival. Turtles Can Fly ▸ Where did the story of the film come from and how did it take shape in your mind? ▸ With inexperienced children who had never acted before, how did you manage to write the dialogues? Ellen Hsiao Historical Background Kurdistan History: up to7th century ♦ c. 614 B.C.: Indo- European tribe came from Asia into the Iranian plateau ♦ 7th century: Conquered by Arabs many converted to Islam Kurdistan History: 7th – 19th ♦ Kurdistan is also occupied by: Seljuk Turks, the Mongols, the Safavid dynasty, and Ottoman Empire (13th century) ♦ 16th-19th: autonomous Kurdish principalities (ended with the collapse of Ottoman Empire) Kurdistan History: after WWI Treaty of Sevres (1920) ♦ It proposed an autonomous homeland for the Kurds ♦ Rich oil in Kurdistan Treaty of Sevres is rejected ♦ Oppression→ from the host countries Kurdish Inhabited Area Kurdish population mainly spread in: ♦ Turkey (12-14 million) ♦ Iran (7-10 million) ♦ Iraq (5-8 million) ♦ Syria (2-3 million) ♦ Armenia (50,000) Kurdistan ♦ Georgia (40,000) Operation Anfal (1986-1989) ♦ Genocide campaign against Kurdish people ♦ 4,500 villages destroyed ♦ 1.1 – 2.1 million death: 860,000 widows Greater number of orphans → → Halabja (Halabcheh) Massacre ♦ March 16, 1988: aka. -

Googoosh and Diasporic Nostalgia for the Pahlavi Modern

Popular Music (2017) Volume 36/2. © Cambridge University Press 2017, pp. 157–177 doi:10.1017/S0261143017000113 Iran’s daughter and mother Iran: Googoosh and diasporic nostalgia for the Pahlavi modern FARZANEH HEMMASI University of Toronto Faculty of Music, 80 Queen's Park, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C5, Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article examines Googoosh, the reigning diva of Persian popular music, through an evaluation of diasporic Iranian discourse and artistic productions linking the vocalist to a feminized nation, its ‘victimisation’ in the revolution, and an attendant ‘nostalgia for the modern’ (Özyürek 2006) of pre-revolutionary Iran. Following analyses of diasporic media that project national drama and desire onto her persona, I then demonstrate how, since her departure from Iran in 2000, Googoosh has embraced her national metaphorization and produced new works that build on historical tropes link- ing nation, the erotic, and motherhood while capitalising on the nostalgia that surrounds her. A well-preserved blonde in her late fifties wearing a silvery-blue, décolletage-revealing dress looks deeply into the camera lens. A synthesised string section swells in the back- ground. Her carefully groomed brows furrow with pained emotion, her outstretched arms convey an exhausted supplication, and her voice almost breaks as she sings: Do not forget me I know that I am ruined You are hearing my cries IamIran,IamIran1 Since the 1979 establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iranian law has dictated that all women within the country’s borders must be veiled; women must also refrain from singing in public except under circumscribed conditions. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

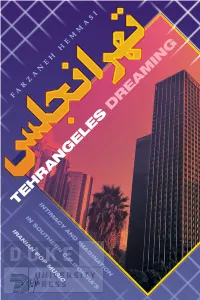

Read the Introduction

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

Iranian Cinema Syllabus Winter 2017 Olli Final Version

Contemporary Iranian Cinema Prof. Hossein Khosrowjah [email protected] Winter 2017: Between January 24and February 28 Times: Tuesday 1-3 Location: Freight & Salvage Coffee House The post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim since the late 1980s for being innovative, ethical, and compassionate. This course will be an overview of post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema. We will discuss and look at works of the most prominent films of this period including Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Bahram Beyzaii, and Asghar Farhadi. We will consider the dominant themes and stylistic characteristics of Iranian national cinema that since its ascendance in the late 1980s has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim for being innovative, ethical and compassionate. Moreover, the role of censorship and strong feminist tendencies of many contemporary Iranian films will be examined. Week 1 [January 24]: Introduction: The Early Days, The Birth of an Industry Class Screenings: Early Ghajar Dynasty Images (Complied by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 18 mins) The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963) Excerpts from Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) 1 Week 2 [January 31]: New Wave Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, The Revolution, and the First Cautious Steps Pre-class viewing: 1- Downpour (Bahram Beyzai, 1972 – Required) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-gCtDWHFQI 2- The Report (Abbas Kiarostami, 1977 – Recommended) http://www.veoh.com/watch/v48030256GmyJGNQw 3- The Brick -

Reflections Poetry Magazine 2021

REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School 1 2 REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School Faculty Advisor: Mr. Fornale Special Thanks: Ms. Subervi, Mrs. Casale, all Grade 5 and ELA Teachers, all students who submitted poetry, and all parents who encouraged them. Art Credit: Front Cover, Conrad Kohl 3 4 Grade 5 5 6 Haiku We unite to fight Darkness that is still in sight. So unite, not fight. by Samer Anshasi Minecraft Minecraft is original It is my favorite game Now Minecraft is getting its biggest update Everything In the world is being redone Crazy new features are being added Really crazy monsters are being put in Amazing blocks and biomes are coming too Fun mechanics are also being added Tools that help you build machines are being added by Zachary Anthenelli Video Games Very Interesting Digital Exciting Out of this world Galactic Addicting Monsterous Excellent Super fun games by Julian Apilado 7 Haiku: Monkeys Swinging on a vine Always wanting bananas Monkeys don’t sit still by Eva Arana Swim Team My coach is named Pat He has a twin brother named Matt. He trains us to swim fast So we don’t end up coming in last. We are the Water Wrats! by Callum Benderoth A Weird Day I don’t want to go to school today it ain’t my birthday but I’ll have fun today Or I’ll be castaway So let's go underway by Grayson P. Breen 8 Seasonal Haikus Spring Fall Spring is cold and hot Fall makes leaves fall down Spring has a lot of pollen Fall makes us were thick jackets Spring has cold long winds Fall makes us rake