Googoosh and Diasporic Nostalgia for the Pahlavi Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Women, Gender, and Music During Wwii a Thesis

EDINBORO UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PITCHING PATRIARCHY: WOMEN, GENDER, AND MUSIC DURING WWII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICS, LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES-HISTORY BY SARAH N. GAUDIOSO EDINBORO, PENNSYLVANIA APRIL 2018 1 Pitching Patriarchy: Women, Music, and Gender During WWII by Sarah N. Gaudioso Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Social Sciences in History ApprovedJjy: Chairperson, Thesis Committed Edinbqro University of Pennsylvania Committee Member Date / H Ij4 I tg Committee Member Date Formatted with the 8th Edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations. i S C ! *2— 1 Copyright © 2018 by Sarah N. Gaudioso All rights reserved ! 1 !l Contents INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 CHAPTER 2: WOMEN IN MUSIC DURING WORLD WAR II 35 CHAPTER 3: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AND MUSIC DURING THE WAR.....84 CHAPTER 4: COMPOSERS 115 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY 128 Gaudioso 1 INTRODUCTION A culture’s music reveals much about its values, and music in the World War II era was no different. It served to unite both military and civilian sectors in a time of total war. Annegret Fauser explains that music, “A medium both permeable and malleable was appropriated for numerous war related tasks.”1 When one realizes this principle, it becomes important to understand how music affected individual segments of American society. By examining women’s roles in the performance, dissemination, and consumption of music, this thesis attempts to position music as a tool in perpetuating the patriarchal gender relations in America during World War II. -

The History of Women in Jazz in Britain

The history of jazz in Britain has been scrutinised in notable publications including Parsonage (2005) The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 , McKay (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain , Simons (2006) Black British Swing and Moore (forthcoming 2007) Inside British Jazz . This body of literature provides a useful basis for specific consideration of the role of women in British jazz. This area is almost completely unresearched but notable exceptions to this trend include Jen Wilson’s work (in her dissertation entitled Syncopated Ladies: British Jazzwomen 1880-1995 and their Influence on Popular Culture ) and George McKay’s chapter ‘From “Male Music” to Feminist Improvising’ in Circular Breathing . Therefore, this chapter will provide a necessarily selective overview of British women in jazz, and offer some limited exploration of the critical issues raised. It is hoped that this will provide a stimulus for more detailed research in the future. Any consideration of this topic must necessarily foreground Ivy Benson 1, who played a fundamental role in encouraging and inspiring female jazz musicians in Britain through her various ‘all-girl’ bands. Benson was born in Yorkshire in 1913 and learned the piano from the age of five. She was something of a child prodigy, performing on Children’s Hour for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) at the age of nine. She also appeared under the name of ‘Baby Benson’ at Working Men’s Clubs (private social clubs founded in the nineteenth century in industrial areas of Great Britain, particularly in the North, with the aim of providing recreation and education for working class men and their families). -

Friday 21 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, September 18, 2020

Friday 21 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, September 18, 2020 (From left) Oud player Noushin Yousefzadeh, kasser drummer (From left) Kasser drummer Negin Heydari, pippeh drummer Noushin Yousefzadeh, a member of the all-women Iranian Negin Heydari, pippeh drummer Malihe Shahinzadeh, and drum- Malihe Shahinzadeh, and drummer Faezeh Mohseni practice music band “Dingo” who plays the Oud (Middle Eastern lute), mer Faezeh Mohseni practise together at a home studio called together at a home studio called the “Dingo room”. poses for a picture as she practises at a home studio called the the “Dingo room”. “Dingo room”. Noushin Yousefzadeh, oud player of the Iranian all-women Noushin Yousefzadeh, a member of the all-women Iranian Women audience members applaud as they attend a perform- music band “Dingo” performs with other band members at a music band “Dingo” who plays the oud (Middle Eastern lute), ance by the Iranian all-women music band “Dingo”. concert. poses for a picture as she practises at a home studio called the “Dingo room”. cording to Sahar Taati, a former director at the music depart- with the dohol and pippeh. So now, whenever authorities arrange ment of Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, festivals and shows like this one in their home town, they apply known as Ershad. and hope they will be selected, even if it means not knowing until Nonetheless, most clerics believe that the sound of female the last minute if they have been. singing is “haram”-or forbidden-because it can be sensuously But, the exhilaration of playing for mixed audiences is worth all stimulating for men and lead to depravity, she added. -

The Influence of Female Jazz Musicians on Music and Society Female Musicians Tend to Go Unrecognized for Their Contributions to Music

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:00 PM - 3:20 PM Swing It Sister: The nflueI nce of Female Jazz Musicians on Music and Society Kirsten Saur Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Saur, Kirsten, "Swing It Sister: The nflueI nce of Female Jazz Musicians on Music and Society" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 15. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/15 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kirsten Saur, 1 Kirsten Saur Swing It, Sister: The Influence of Female Jazz Musicians on Music and Society Female musicians tend to go unrecognized for their contributions to music. Though this has changed in recent years, the women of the past did not get the fame they deserved until after their deaths. Women have even tried to perform as professional musicians since ancient Greek times. But even then, the recognition did not go far. They were performers but were not seen as influences on music or social standings like male composers and performers were. They were not remembered like male performers and composers until past their time, and the lives of these women are not studied as possible influences in music until far past their times as well. -

Representations of Women in Music Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1999 Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos Jan E. Urbina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Urbina, Jan E., "Creativity Or Collusion?: Representations of Women in Music Videos" (1999). Master's Theses. 4125. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4125 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVITYOR COLLUSION?: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN INMUSIC VIDEOS by Jan E. Urbina A Thesis Submittedto the Facuhy of The GraduateCollege in partial folfitlment of the requirementsfor the Degree of Master of Arts Departmentof Sociology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1999 Copyright by Jan E. Urbina 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are certain individuals that touch our lives in profound and oftentimes unexpected ways. When we meet them we feel privileged because they positively impact our lives and help shape our futures, whether they know it or not. These individuals stand out as exceptional in our hearts and in our memories because they inspire us to aim high. They support our dreams and goals and guide us toward achieving them They possess characteristics we admire, respect, cherish, and seekto emulate. These individuals are our mentors, our role models. Therefore, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to the outstanding members ofmy committee, Dr. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

The Garden of Heaven - Poems of Hafiz Pdf

FREE THE GARDEN OF HEAVEN - POEMS OF HAFIZ PDF Hafiz | 112 pages | 04 Nov 2003 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486431611 | English | New York, United States All About Heaven - Observations placeholder His life and poems have become the subjects of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing postth century Persian writing more than any other author. Hafez is best known for his poems that can be described as " antinomian " [7] and with the medieval use of the term "theosophical"; the term " theosophy " in the 13th and 14th centuries was used to indicate mystical work by "authors only inspired by the holy books " as distinguished from theology. Hafez primarily wrote in the literary genre of lyric poetry or ghazalsthat is the ideal style for expressing the ecstasy of divine inspiration in the mystical form of love poems. He was a Sufi. Themes of his ghazals include the beloved, faith and exposing hypocrisy. In his ghazals he deals with love, wine and taverns, all presenting ecstasy and freedom from restraint, whether in actual worldly release or in the voice of the lover [8] speaking of divine love. His tomb is visited often. Adaptations, imitations and translations of his poems exist in all major languages. Hafez was born in Shiraz The Garden of Heaven - Poems of Hafiz, Iran. Despite his profound effect on Persian life and culture and his enduring popularity and influence, few details of his life are known. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional anecdotes. Early tazkiras biographical sketches mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable. Modern scholars generally agree that Hafez was born either in or According to an account by JamiHafez died in Twenty years after his death, a tomb, the Hafeziehwas erected to honor Hafez in the Musalla Gardens in The Garden of Heaven - Poems of Hafiz. -

Siamak Shirazi Babak Amini

SIAMAK SHIRAZI BABAK AMINI NW TOUR - 2020 ARTISTS BaSiaNova is a musical collaboration between Babak Amini and Siamak Shirazi which started in Winter of 2017. Their unique perspectives about music and life is expressed in their upcoming album, coming out this Fall, and live performances. MUSIC They are combining more than 30 years of Babak’s experience as an award-winning performer, composer, arranger, and producer, and Siamak’s experience as a wellness guru and a vocalist. Their sound represents a fusion between Jazz, Flamenco, and contemporary Persian music and creates a rare, Avangard style of live performance. SIAMAK SHIRAZI Siamak has a natural talent for music which started manifesting as early as when he was two years old. He grew up in a family who loved and enjoyed music. He started reciting poetry and singing when he was six years old. Music has remained to be an anchor for his soul through the rough seas of his life, and he always found a way to return to this natural outlet for expression of his innermost feelings. Siamak used to be a professional singer in mid-1980s but set that aside to attend college and later, build a career in Wellness Based Medicine. However, in addition to growing his wellness enterprise, Siamak has always remained a music lover and a musician at heart. And now after taking a 25-year hiatus, he is returning back to music.He is privileged to collaborate with one of the best in the business, Mr. Babak Amini on his comeback project. Babak has been an essential part of Siamak’s vision for his return to singing, and his beautiful soul is ever-present as the energy which is traveling through Siamak’s voice. -

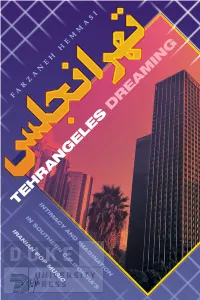

Read the Introduction

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try.