In Iranian Cinema: Bashu, Little Stranger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Persian 1103 Course Change.Pdf

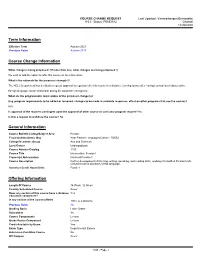

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 1103 - Status: PENDING Chantal 11/20/2020 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2021 Previous Value Autumn 2015 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) We wish to add the option to offer this course as an online class. What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The NELC Department has decided to request approval to regularly offer this course in a distance learning format after having learned much about online foreign language course instruction during the pandemic emergency. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? N/A Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Persian Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Near Eastern Languages/Culture - D0554 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 1103 Course Title Intermediate Persian I Transcript Abbreviation Intermed Persian 1 Course Description Further development of listening, writing, speaking, and reading skills; reading of simplified Persian texts. Closed to native speakers of this language. Semester Credit Hours/Units Fixed: 4 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 12 Week Flexibly -

Research Paper Impact Factor

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 3.072 E- ISSN -2347-856X Peer Reviewed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653 HISTORY OF INDIAN CINEMA Dr. B.P.Mahesh Chandra Guru * Dr.M.S.Sapna** M.Prabhudev*** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar**** * Professor, Dept. of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. **Assistant Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***RGNF Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore-570006, Karnataka, India. Abstract The Lumiere brothers came over to India in 1896 and exhibited some films for the benefit of publics. D.G.Phalke is known as the founding father of Indian film industry. The first Indian talkie film Alam Ara was produced in 1931 by Ardeshir Irani. In the age of mooki films, about 1000 films were made in India. A new age of talkie films began in India in 1929. The decade of 1940s witnessed remarkable growth of Indian film industry. The Indian films grew well statistically and qualitatively in the post-independence period. In the decade of 1960s, Bollywood and regional films grew very well in the country because of the technological advancements and creative ventures. In the decade of 1970s, new experiments were conducted by the progressive film makers in India. In the decade of 1980s, the commercial films were produced in large number in order to entertain the masses and generate income. Television also gave a tough challenge to the film industry in the decade of 1990s. -

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Blogging Iran – a Case Study of Iranian English Language Weblogs

UNIVERSITY OF OSLO FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES TIK Centre for technology, innovation and culture P.O. BOX 1108 Blindern N-0317 OSLO Norway http://www.tik.uio.no ESST The European Inter-University Association on Society, Science and Technology http://www.esst.uio.no The ESST MA Blogging Iran – A Case Study of Iranian English Language Weblogs Peder Are Nøstvold Jensen University of Oslo Nature and Culture 2004 24.819 Words 1 Supervisor for this Master thesis has been Professor Terje Rasmussen from the Department of Media and Communication, the University of Oslo, Norway. I would also like to thank Elisabeth Staksrud from Statens Filmtilsyn for valuable information, and for pointing me to the Nordic Institute for Asian Studies (NIAS) in Copenhagen, Denmark, who were kind enough to offer me a scholarship and the opportunity to use their library. James Gomez was generous enough to send me his excellent new book Asian Cyberactivism for free. Last, but not least, I have to thank Mr. Hossein Derakhshan for spending some of his time giving me information and granting me an interview. Without him, and the other Iranian webloggers described here, this Master thesis would not have been possible. 2 Chapter outline of thesis: 1 Motivation 2. Methodology 3. The Internet and censorship 4. Background on Internet censorship in several countries 4.1 The case of China 4.2 The case of Singapore 4.3 Burma 5. The situation in Iran – Politics and censorship 6. Weblogs 6.1 About weblogs 6.2 Iranian weblogs 6.3 About description of weblogs 7. Weblogs – case studies 7.1 Weblogs by Insiders, Iranians in Iran 7.1.1 Additional weblogs by Insiders 7.2 Weblogs by Outsiders, Iranians in exile 7.3 Summary, and conclusion about weblog findings 8. -

Read the Introduction

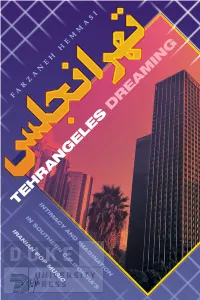

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Iranian Cinema Syllabus Winter 2017 Olli Final Version

Contemporary Iranian Cinema Prof. Hossein Khosrowjah [email protected] Winter 2017: Between January 24and February 28 Times: Tuesday 1-3 Location: Freight & Salvage Coffee House The post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim since the late 1980s for being innovative, ethical, and compassionate. This course will be an overview of post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema. We will discuss and look at works of the most prominent films of this period including Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Bahram Beyzaii, and Asghar Farhadi. We will consider the dominant themes and stylistic characteristics of Iranian national cinema that since its ascendance in the late 1980s has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim for being innovative, ethical and compassionate. Moreover, the role of censorship and strong feminist tendencies of many contemporary Iranian films will be examined. Week 1 [January 24]: Introduction: The Early Days, The Birth of an Industry Class Screenings: Early Ghajar Dynasty Images (Complied by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 18 mins) The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963) Excerpts from Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) 1 Week 2 [January 31]: New Wave Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, The Revolution, and the First Cautious Steps Pre-class viewing: 1- Downpour (Bahram Beyzai, 1972 – Required) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-gCtDWHFQI 2- The Report (Abbas Kiarostami, 1977 – Recommended) http://www.veoh.com/watch/v48030256GmyJGNQw 3- The Brick -

Data Collection Survey on Tourism and Cultural Heritage in the Islamic Republic of Iran Final Report

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN IRANIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE, HANDICRAFTS AND TOURISM ORGANIZATION (ICHTO) DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON TOURISM AND CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) HOKKAIDO UNIVERSITY JTB CORPORATE SALES INC. INGÉROSEC CORPORATION RECS INTERNATIONAL INC. 7R JR 18-006 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON TOURISM AND CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ v Maps ........................................................................................................................................ vi Photos (The 1st Field Survey) ................................................................................................. vii Photos (The 2nd Field Survey) ............................................................................................... viii Photos (The 3rd Field Survey) .................................................................................................. ix List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................ x 1. Outline of the Survey ....................................................................................................... 1 (1) Background and Objectives ..................................................................................... -

Bombay Talkies

A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and The Bombay Talkies Debashree Mukherjee Encounters, Exile, Belonging The story of how Josef Wirsching came to work in Bombay is fascinating and full of meandering details. In brief, it’s a story of creative confluence and, well, serendipity … the right people with the right ideas getting together at the right time. Thus, the theme of encounters – cultural, personal, intermedial – is key to understanding Josef Wirsching’s career and its significance. Born in Munich in 1903, Wirsching experienced all the cultural ferment of the interwar years. Cinema was still a fledgling art form at the time, and was radically influenced by Munich’s robust theatre and photography scene. For example, the Ostermayr brothers (Franz, Peter, Ottmarr) ran a photography studio, studied acting, and worked at Max Reinhardt’s Kammertheater before they turned wholeheartedly to filmmaking. Josef Wirsching himself was slated to take over his father’s costume and set design studios, but had a career epiphany when he was gifted a still camera on his 16th birthday. Against initial family resistance, Josef enrolled in a prestigious 1 industrial arts school to study photography and subsequently joined Weiss-Blau-Film as an apprentice photographer. By the early 1920s, Peter Ostermayr’s Emelka film company had 51 Projects / Processes become a greatly desired destination for young people wanting to make a name in cinema. Josef Wirsching joined Emelka at this time, as did another young man named Alfred Hitchcock. Back in India, at the turn of the century, Indian artists were actively trying to forge an aesthetic language that could be simultaneously nationalist as well as modern. -

Download Being the Number of Sent Packets That Were Acknowledged As Received

Dimming the Internet Detecting Throttling as a Mechanism of Censorship in Iran Collin Anderson? [email protected] Abstract. In the days immediately following the contested June 2009 Presidential election, Iranians attempting to reach news content and so- cial media platforms were subject to unprecedented levels of the degra- dation, blocking and jamming of communications channels. Rather than shut down networks, which would draw attention and controversy, the government was rumored to have slowed connection speeds to rates that would render the Internet nearly unusable, especially for the consump- tion and distribution of multimedia content. Since, political upheavals elsewhere have been associated with headlines such as \High usage slows down Internet in Bahrain" and \Syrian Internet slows during Friday protests once again," with further rumors linking poor connectivity with political instability in Myanmar and Tibet. For governments threatened by public expression, the throttling of Internet connectivity appears to be an increasingly preferred and less detectable method of stifling the free flow of information. In order to assess this perceived trend and begin to create systems of accountability and transparency on such practices, we attempt to outline an initial strategy for utilizing a ubiquitious set of network measurements as a monitoring service, then apply such method- ology to shed light on the recent history of censorship in Iran. Keywords: censorship, national Internet, Iran, throttling, M-Lab 1 Introduction "Prison is like, there's no bandwidth." - Eric Schmidt1 The primary purpose of this paper is to assess the validity of claims that the international connectivity of information networks used by the Iranian public has been subject to substantial throttling based on a historical and correlated set of open measurements of network performance.