King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Download Our Annual Report 2013

For a brighter Annual Report 2013 future New Israel Fund Chairman’s Report OUR MISSION We believe that Israel can live up to its founders’ vision of Dear Friends a state that “ensures complete equality of social and political rights 2013 was a successful year for NIF UK. Thanks to our supporters, we raised a record £1.7 million and we reached out to an increasing number of people in terms of events and donors. to all its inhabitants, without regard to religion, race or gender”. NIF’s 2013 activities appear distant when reviewed against the terrible events of now, summer 2014. However, for those committed to equality, social justice and human rights in Israel the significant achievements of 2013 continued NIF’s vital work that ensures that understandable social tension at this time of national concern and the fear of the moment do not allow the ABOUT THE NEW ISRAEL FUND forces of intolerance to flourish. New Israel Fund UK raises funds and NIF continues to be a leading force The funds generated allowed Israelis to work across the community to combat racism and to provides support to organisations and advancing a more tolerant, just and fight the appalling phenomena of ‘price tag’ revenge attacks. The increasingly powerful voice projects in Israel while educating and democratic Israel. Our extensive presence raising awareness of this work in the in Israel – including a diverse staff and and actions of Tag Meir and our Shared Society programme brought together communities, UK. We are part of an international consultant pool of 100 people – and to say no to hatred in a most practical way. -

Jews and the West Legalization of Marijuana in Israel?

SEPTEMBER 2014 4-8 AMBASSADOR LARS FAABORG- ANDERSEN: A VIEW ON THE ISRAELI – PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 10-13 H.Е. José João Manuel THE FIRST AMBASSADOR OF ANGOLA TO ISRAEL 18-23 JEWS AND THE WEST AN OPINION OF A POLITOLOGIST 32-34 LEGALIZATION OF MARIJUANA IN ISRAEL? 10 Carlibah St., Tel-Aviv P.O. Box 20344, Tel Aviv 61200, Israel 708 Third Avenue, 4th Floor New York, NY 10017, U.S.A. Club Diplomatique de Geneva P.O. Box 228, Geneva, Switzerland Publisher The Diplomatic Club Ltd. Editor-in-Chief Julia Verdel Editor Eveline Erfolg Dear friends, All things change, and the only constant in spectrum of Arab and Muslim opinions, Writers Anthony J. Dennis the Middle East is a sudden and dramatic just as there is a spectrum of Jewish Patricia e Hemricourt, Israel change. opinions. Ira Moskowitz, Israel The Middle East is a very eventful region, As one of the most talented diplomats in Bernard Marks, Israel where history is written every day. Here history of diplomacy, Henry Kissinger Christopher Barder, UK you can witness this by yourself. It could said: “It is not a matter of what is true that Ilan Berman, USA be during, before or after a war – between counts, but a matter of what is perceived wars. South – North, North – South, to be true.” war – truce, truce – war, enemy – friend, Reporters Ksenia Svetlov Diplomacy, as opposed to war, facilitates Eveline Erfolg friend – enemy… Sometimes, these words (or sometimes hinders) conflict prevention David Rhodes become very similar here. and resolution, before armed conflict Neill Sandler “A la guerre comme à la guerre” and begins. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Netanyahu Meets US Jewish Leaders, Addresses Western Wall

TOP Opinion. Tradition. CYCLING WHO'S THE CHALLENGE RACE TO BANKROLLING JEWISH OF JEWISH OPEN IN VOICE FOR PEACE? REPENTANCE ISRAEL A2. A10. A11. THE algemeiner JOURNAL A Good & Healthy New Year 5778 $1.00 - PRINTED IN NEW YORK FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 | 2 TISHREI 5778 VOL. XLV NO. 2324 Netanyahu Meets Media in Turkey Inciting Anti-semitism US Jewish Leaders, Over Kurdish Addresses Western Independence Wall Controversy Referendum BY BEN COHEN As the impending referendum on independence for the Kurdish region of Iraq draws closer, pro-government media outlets in Turkey – which remains bitterly opposed to Kurdish self-determination – are energetically promoting conspiracy theories centered on the alleged relations between Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani and the Israeli authorities. Women of the Wall members read from the Torah at the Robinson's Arch egalitarian prayer site, near the Western Wall plaza. Photo: Woman of the Wall. Israelis of Kurdish origin demonstrating at the Turkish Embassy in Tel Aviv in 2010. Photo: File. Th e latest antisemitic salvo in the Turkish press claims that Barzani and the Israelis have agreed on the BY JNS.ORG Several unnamed sources sented at the meeting included resettlement of 200,000 Jews in territory controlled by the who attended the meeting said the American Israel Public Aff airs Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq following “Th e meeting took place in an outcome was “good” and “positive,” Committee (AIPAC), the Confer- the referendum – currently scheduled for September 25. excellent atmosphere,” according reported Haaretz, with Netanya- ence of Presidents of Major While Kurdish leaders are reported to be considering “alter- to a statement released by the hu’s approach "forthcoming." But American Jewish Organizations, natives” to the referendum given the international unease Prime Minister’s Offi ce. -

Read the Introduction

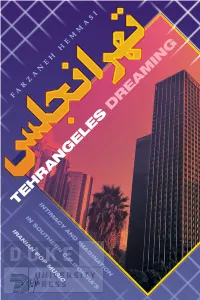

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström

Online version of Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström Stockholm, Svenskt visarkiv, 2003 Publications issued by Svenskt visarkiv 18 Translated by Kristina Radford & Andrew Coultard Illustrations: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist For additional material, go to http://old.visarkiv.se/online/online_mmm.html Contents Preface.................................................................................................. 9 AIMS, THEMES AND TERMS Aims, emes and Terms...................................................................... 13 Music as Objective and Means— Expression and Cause, · Assumptions and Questions, e Production of Difference ............................................................... 20 Class and Ethnicity, · From Similarity to Difference, · Expressive Forms and Aesthet- icisation, Visibility .............................................................................................. 27 Cultural Brand-naming, · Representative Symbols, Diversity and Multiculture ................................................................... 33 A Tradition of Liberal ought, · e Anthropological Concept of Culture and Post- modern Politics of Identity, · Confusion, Individuals, Groupings, Institutions ..................................................... 44 Individuals, · Groupings, · Institutions, Doers, Knowers, Makers ...................................................................... 50 Arenas ................................................................................................. -

Ester Rada /Izraēla/ Line up –

MĀKSLINIEKU INFO 2015 Katru gadu jūlijā… Ester Rada /Izraēla/ line up – Ester Rada - vokāls Ben Hoze - ģitāra, Michael Guy - bass, Lior Romano - taustiņi, Gal Dahan - saksofons, Inon Peretz - trompete, Maayan Milo - trombons, Dan Mayo - sitaminstrumenti www.esterrada.com Koncerts: 2015. gada 2. jūlijā, Rīgas Kongresu namā ESTERE RADA ir vokāliste un komponiste kuras muzikālā skanējuma dažādība saistāma ar viņas kultūras mantojumu – viņa ir Izraēlā dzimusi etiopiete. Apvienojot R&B, džezu, regeju, fanku un etiopiešu mūziku, ieguvusi popularitāti un kritiķu atsauksmes Eiropā, ASV un Kanādā. Estere Rada jau bijusi tūrē ASV un Kanādā, uzstājusies arī vairākās Eiropas valstīs, leģendāro Glastonberijas festivālu Anglijā ieskaitot, bijusi iesildošā mūziķe Alīšas Kīsas koncertā Izraēlā un tikusi nominēta MTV mūzikas balvai kā labākā izraēļu izpildītāja. Viņas neparastais un kolorītais videoklips “Life Happens” raisījis gana lielu interesi YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_QFQCvdtyw), kur pārsniedzis jau pusmiljona skatījumu atzīmi, un tiek demonstrēts vairākos Eiropas mūzikas TV kanālos. Dziesma iekļauta arī 2013. gadā klajā nākušajā tāda paša nosaukuma miniplatē un pērn izdotajā pilnmetrāžas debijas albumā. Esteri Radu mūzikas kritiķi dažādās pasaules malās jau salīdzinājuši ar tādām leģendām kā Nina Simone un Aretha Franklin. Viņa arīdzan salīdzināta ar mūsdienu soul dīvām Erykah Badu un Lauryn Hill. Un salīdzinājumi ir vietā, jo viss liecina par jaunas dīvas iemirdzēšanos. Esteres unikālo muzicēšanas stilu veido soulmūzikā ietverts -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/29/2015 2:03:59 PM U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/29/2015 2:03:59 PM OMB No. 1124-0002; Expires April 30,2017 u.s. Department of justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2015 (Insert date) I-REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Ceisler Media & Issue Advocacy, LLC 6266 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 1525 Locust Street Sixth Floor Philadelphia, PA 19102 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No • (2) Citizenship Yes • No • (3) Occupation Yes • No • (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes • No H • (2) Ownership or control Yes • No _ (3) Branch offices Yes • No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No B If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? YesD Nod] If no, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, for which ho printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an : organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

2009 Mcnair Scholars Journal

The McNair Scholars Journal of the University of Washington Volume VIII Spring 2009 THE MCNAIR SCHOLARS JOURNAL UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON McNair Program Office of Minority Affairs University of Washington 375 Schmitz Hall Box 355845 Seattle, WA 98195-5845 [email protected] http://depts.washington.edu/uwmcnair The Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program operates as a part of TRIO Programs, which are funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Cover Art by Jeff Garber www.jeffgarberphoto.com University of Washington McNair Program Staff Program Director Gabriel Gallardo, Ph.D. Associate Director Gene Kim, Ph.D. Program Coordinator Rosa Ramirez Graduate Student Advisors Audra Gray Teresa Mares Ashley McClure Hoang Ngo McNair Scholars‘ Research Mentors Dr. Rick Bonus, Department of American Ethnic Studies Dr. Sarah Bryant-Bertail, Department of Drama Dr. Tony Gill, Department of Political Science Dr. Doug Jackson, Department of Oral Medicine Dr. Bryan D. Jones, U.W. Center of Politics and Public Policy Dr. Ralina Joseph, Department of Communications Dr. Elham Kazemi, Department of Education Dr. Neal Lesh, Department of Computer Engineering Dr. Firoozeh Papan-Matin, Persian and Iranian Studies Program Dr. Dian Million, American Indian Studies Program Dr. Aseem Prakas, Department of Political Science Dr. Kristin Swanson, Department of Pathology Dr. Ed Taylor, Dean of Undergraduate Academic Affair/ Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Dr. Susan H. Whiting, Department of Political Science Dr. Shirley Yee, Department of Comparative History of Ideas Volume VIII Copyright 2009 ii From the Vice President and Vice Provost for Diversity One of the great delights of higher education is that it provides young scholars an opportunity to pursue research in a field that interests and engages them. -

April 2018 a Monthly Guide to Living in Basel

BLUES & JAZZ FESTIVALS • BRICKLIVE • MUBA • ROCKY HORROR SHOW Volume 6 Issue 7 CHF 6 6 A Monthly Guide to Living in Basel April 2018 Daily Non-Stop Bus to/from Basel Badischer Bahnhof +49 (0)7626 91610 [email protected] Black Forest Academy bfacademy.de EXTRAKONZERT COLLEGIUM MUSICUM Magical BASEL Cafe ANDREAS SCHOLL New ! Play Cafe in Basel COUNTERTENOR Unveil the magic... «AMATO BENE» LEBRAT CE E GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL X LA E RN & Wassermusik, Arien und Rezitative R A GR LE O W aus «Rodelina», «Giustino», «Giulio Cesare» FUN VE A H SHOP ARVO PÄRT aus Wallfahrtslied FELIX MENDELSSOHN Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Wellingtons Sieg KEVIN GRIFFITHS | Dirigent Vorverkauf: Kulturhaus Bider & Tanner, Telefon 061 206 99 96, [email protected] Do not litter - images by freepik und weitere Vorverkaufsstellen Reduzierte Tickets für Kinder, Jugendliche, Max Kämpf Platz 2 4058 Basel 078 905 37 38 Studenten: CHF 15.— [email protected] Tuesday > Saturday www.collegiummusicumbasel.ch Riehenring Swiss www.magicalcafe.ch 8.30 am > 5.30 pm Intern. angentenweg rlenmattstr. T School Friday E rlenstr. or join us on FREITAG, 13. APRIL 2018 13. FREITAG, BASEL THEATER MUSICAL 8.30 am > 7.00 pm E 19.30 UHR Musical Theater 2 Basel Life Magazine / www.basellife.com LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Readers, Spring in Basel resonates with the sounds of the returning songbirds as well as a variety of music festivals. Turn the page to learn all about the fabulous Jazzfestival Basel, its history, its mission, and the fantastic line- April 2018 Volume 6 Issue 7 up of world-class bands that will be gracing our city in the next few weeks.