Social Penetration and Police Action: Collaboration Structures in the Repertory of Gestapo Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Deutsche Ordnungspoli2ei Und Der Holocaust Im Baltikum Und in Weissrussland 1941-1944

WOLFGANG CURILLA DIE DEUTSCHE ORDNUNGSPOLI2EI UND DER HOLOCAUST IM BALTIKUM UND IN WEISSRUSSLAND 1941-1944 2., durchgesehene Auflage FERDINAND SCHONINGH Paderborn • Munchen • Wien • Zurich INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort 11 Einleitung 13 ERSTER TEIL: GRUNDLAGEN UND VORAUSSETZUNGEN .... 23 1. Entrechtung der Juden 25 2. Ordnungspolizei 49 3. Die Vorbereitung des Angriffs auf die Sowjetunion 61 4. Der Auftrag an die Einsatzgruppen 86 ZWEITER TEIL: DIE TATEN 125 ERSTER ABSCHNITT: SCHWERPUNKT BALTIKUM 127 5. Staatliche Polizeidirektion Memel und Kommando der Schutzpolizei Memel 136 6. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 11 150 7. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 65 182 8. Schutzpolizei-Dienstabteilung Libau 191 9. Polizeibataillon 105 200 10. Reserve-Polizei-Kompanie z.b.V. Riga 204 11. Kommandeur der Schutzpolizei Riga 214 12. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 22 244 13. Andere Polizeibataillone 262 I. Polizeibataillon 319 262 II. Polizeibataillon 321 263 III. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 53 264 ZWEITER ABSCHNITT: RESERVE-POLIZEIBATAILLONE 9 UND 3 - SCHWERPUNKT BALTIKUM 268 14. Einsatzgruppe A/BdS Ostland 274 15. Einsatzkommando 2/KdS Lettland 286 16. Einsatzkommando 3/KdS Litauen 305 DRITTER ABSCHNITT: SCHUTZPOLIZEI, GENDARMERIE UND KOMMANDOSTELLEN 331 17. Schutzpolizei 331 18. Polizeikommando Waldenburg 342 g Inhaltsverzeichnis 19. Gendarmerie 349 20. Befehlshaber der Ordnungspolizei Ostland 389 21. Kommandeur der Ordnungspolizei Lettland 392 22. Kommandeur der Ordnungspolizei Weifiruthenien 398 VLERTER ABSCHNITT: RESERVE-POLIZEIBATAILLONE 9 UND 3 - SCHWERPUNKT WEISSRUSSLAND 403 23. Einsatzkommando 9 410 24. Einsatzkommando 8 426 25. Einsatzgruppe B 461 26. KdS WeiSruthenien/BdS Rufiland-Mitte und Weifiruthenien 476 F0NFTER ABSCHNITT: SCHWERPUNKT WEISSRUSSLAND 503 27. Polizeibataillon 309 508 28. Polizeibataillon 316 527 29. Polizeibataillon 322 545 30. Polizeibataillon 307 569 31. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 13 587 32. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 131 606 33. -

Social Penetration and Police Action: Collaboration Structures in the Repertory of Gestapo Activities

Social Penetration and Police Action: Collaboration Structures in the Repertory of Gestapo Activities KLAUS-MICHAEL MALLMANN* SUMMARY: The twentieth century was "short", running only from 1914 to 1990/ 1991. Even so, it will doubtless enter history as an unprecedented era of dictatorships. The question of how these totalitarian regimes functioned in practice, how and to what extent they were able to realize their power aspirations, has until now been answered empirically at most highly selectively. Extensive comparative research efforts will be required over the coming decades. The police as the key organization in the state monopoly of power is particularly important in this context, since like no other institution it operates at the interface of state and society. Using the example of the Gestapo's activities in the Third Reich, this article analyses collaboration structures between these two spheres, which made possible (either on a voluntary or coercive basis) a penetration of social contexts and hence police action even in shielded areas. It is my thesis that such exchange processes through unsolicited denunciation and informers with double identities will also have been decisive outside Germany in the tracking of dissident behaviour and the detection of conspiratorial practices. I do not think it is too far-fetched to say that the century which is about to end will go down in history as the era of dictatorships. But a social history of this state-legitimized and -executed terror, let alone an interna- tional comparison on a solid -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Die Polizei Im NS-Staat

INHALTSVERZEICHNIS VORWORT 9 EINLEITUNG 11 I. TEIL: POLIZEIBEGRIFF - POLIZEIRECHT 1. Der Polizeibegriff und seine Verwendung in der Neuzeit . 13 2. Rechtsgrundlagen für die Polizei 17 II. TEIL: DIE POLIZEI IN DER ENDPHASE DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK 1. Die Polizeibehörden in der Weimarer Republik 22 2. Die Situation der Polizei in der Schlußphase der Weimarer Republik 28 3. Der »Preußenschlag« und seine Auswirkung auf die preußische Polizei 32 III. TEIL: DER ZUGRIFF DER NATIONALSOZIALISTEN AUF DIE POLIZEI 1. Die Übernahme der Polizeigewalt durch die National- sozialisten 37 2. Die Verselbständigung der Politischen Polizei 40 3. Die Aufstellung von Formationen »zur Unterstützung« der Polizei 47 a) Hilfspolizei 47 b) »Polizeiabteilung Wecke z.b.V.« 48 c) Politische Bereitschaften 50 d) Das Feldjägerkorps 51 4. Die Verhängung von Schutzhaft und die Errichtung von Konzentrationslagern 53 5. Die Übernahme der Polizeihoheit durch das Reich 60 6. Die »Gleichschaltung« der polizeilichen Interessen- verbände 63 7. Die Militarisierung der Schutzpolizei und ihre Überführung in die Wehrmacht 65 8. NS-Propaganda: »Die Polizei - Dein Freund und Helfer« 70 Inhaltsverzeichnis IV. TEIL: DIE »VERREICHLICHUNG« DER POLIZEI UND IHRE VERSCHMELZUNG MIT DER SS P . j 1. Die Vorbereitung der »Verreichlichung« der Polizei 73 ") 2. Die Ernennung des Reichsführers-SS zum Chef der 1_ Deutschen Polizei im Reichsministerium des Innern 74 3. Die Neuordnung der Sicherheitspolizei 78 a) Der Ausbau der Geheimen Staatspolizei 78 b) Die Einsetzung von Inspekteuren der Sicherheitspolizei 79 c) Die Neuordnung der Kriminalpolizei 81 4. Die Entwicklung der Ordnungspolizei und der Gendarmerie 83 a) Die Kommandostruktur des Hauptamtes Ordnungspolizei 83 b) Die Einsetzung von Inspekteuren der Ordnungs- polizei 84 c) Die Schutzpolizei 85 d) Die Umgestaltung der Landjägerei 86 5. -

Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky

Hamburg University Press Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky Hamburger Universitätsreden Neue Folge 3 Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky Hamburger Universitätsreden Neue Folge 3 Herausgeber: Der Präsident der Universität Hamburg ZUM GEDENKEN AN PETER BOROWSKY herausgegeben von Rainer Hering und Rainer Nicolaysen Hamburg University Press © 2003 Peter Borowsky INHALT 9 Zeittafel Peter Borowsky 15 Vorwort 17 TRAUERFEIER FRIEDHOF HAMBURG-NIENSTEDTEN, 20. OKTOBER 2000 19 Gertraud Gutzmann Nachdenken über Peter Borowsky 25 Rainer Nicolaysen Trauerrede für Peter Borowsky 31 GEDENKFEIER UNIVERSITÄT HAMBURG, 8. FEBRUAR 2001 33 Wilfried Hartmann Grußwort des Vizepräsidenten der Universität Hamburg 41 Barbara Vogel Rede auf der akademischen Gedenkfeier für Peter Borowsky 53 Rainer Hering Der Hochschullehrer Peter Borowsky 61 Klemens von Klemperer Anderer Widerstand – anderes Deutschland? Formen des Widerstands im „Dritten Reich“ – ein Überblick 93 GEDENKFEIER SMITH COLLEGE, 27. MÄRZ 2001 95 Joachim Stieber Peter Borowsky, Member of the Department of History in Recurring Visits 103 Hans Rudolf Vaget The Political Ramifications of Hitler’s Cult of Wagner 129 ANHANG 131 Bibliographie Peter Borowsky 139 Gedenkschrift für Peter Borowsky – Inhaltsübersicht 147 Rednerinnen und Redner 149 Impressum ZEITTAFEL Peter Borowsky 1938 Peter Borowsky wird am 3. Juni als Sohn von Margare- te und Kurt Borowsky, einem selbstständigen Einzel- handelskaufmann, in Angerburg/Ostpreußen geboren 1944 im Herbst Einschulung in Angerburg 1945 nach der Flucht aus Ostpreußen von Januar -

German History Reflected

The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected GFE = 1/2 Formathöhe The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected Contents 3 Introduction 44 Reunification and Change 46 The euphoria of unity 4 The Reich Aviation Ministry 48 A tainted place 50 The Treuhandanstalt 6 Inception 53 The architecture of reunification 10 The nerve centre of power 56 In conversation with 14 Courage to resist: the Rote Kapelle Hans-Michael Meyer-Sebastian 18 Architecture under the Nazis 58 The Federal Ministry of Finance 22 The House of Ministries 60 A living place today 24 The changing face of a colossus 64 Experiencing and creating history 28 The government clashes with the people 66 How do you feel about working in this building? 32 Socialist aspirations meet social reality 69 A stroll along Wilhelmstrasse 34 Isolation and separation 36 Escape from the state 38 New paths and a dead-end 72 Chronicle of the Detlev Rohwedder Building 40 Architecture after the war – 77 Further reading a building is transformed 79 Imprint 42 In conversation with Jürgen Dröse 2 Contents Introduction The Detlev Rohwedder Building, home to Germany’s the House of Ministries, foreshadowing the country- Federal Ministry of Finance since 1999, bears wide uprising on 17 June. Eight years later, the Berlin witness to the upheavals of recent German history Wall began to cast its shadow just a few steps away. like almost no other structure. After reunification, the Treuhandanstalt, the body Constructed as the Reich Aviation Ministry, the charged with the GDR’s financial liquidation, moved vast site was the nerve centre of power under into the building. -

Special Motivation - the Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S

Special Motivation - The Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S. Zapotoczny "...Then, stark naked, they had to run down more steps to an underground corridor that Led back up the ramp, where the gas van awaited them." Franz Schalling Einsatzgruppen policeman Like every historical event, the Holocaust evokes certain specific images. When mentioning the Holocaust, most people think of the concentration camps. They immediately envision emaciated victims in dirty striped uniforms staring incomprehensibly at their liberators or piles of corpses, too numerous to bury individually, bulldozed into mass graves. While those are accurate images, they are merely the product of the systematization of the genocide committed by the Third Reich. The reality of that genocide began not in the camps or in the gas chambers but with four small groups of murderers known as the Einsatzgruppen. Formed by Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer-SS, and Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), they operated in the territories captured by the German armies with the cooperation of German army units (Wehrmacht ) and local militias. By the spring of 1943, when the Germans began their retreat from Soviet territory, the Einsatzgruppen had murdered 1.25 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian and Soviet nationals, including prisoners of war. The Einsatzgruppen massacres preceded the invention of the death camps and significantly influenced their development. The Einsatzgruppen story offers insight into a fundamental Holocaust question of what made it possible for men, some of them ordinary men, to kill so many people so ruthlessly. The members of the Einsatzgruppen had developed a special motivation to kill. -

Panzerfahrzeuge Und Panzereinheiten Der Ordnungspolizei

Seite VII. FARB ANSTRICHE DER PANZER UND KRAFTFAHRZEUGE 192 VIII. ERKENNUNGSZEICHEN UND BESCHRIFTUNGEN 197 Allgemeines 197 Hoheitsabzeichen 197 Balkenkreuze 197 Amtliches Kennzeichen 199 RMdL-Nummern 199 Truppenkennzeichen 200 Sonstige Kennzeichen und Beschriftungen 202 IX. UNIFORMEN UND AUSRÜSTUNG 205 Allgemeines 205 Ausstattung der Polizeibeamten im auswärtigen Einsatz 205 Sonderbekleidung für die Besatzung der Sonderwagen bzw. Panzerwagen 206 X. DIE GEPANZERTEN FAHRZEUGE DER ORDNUNGSPOLIZEI 215 Beschaffung und Zuführung von Panzerfahrzeugen 215 Typentafeln 217 ANLAGEN 265 Anlage 1: Verteilung der Pol.-Sonderkraftwagen der Ordnungspolizei 1939 265 Anlage 2: Stärkenachweisung Polizei M.G. Hundertschaft (mot.), 15.5.1938 268 3. (Polizei-Sonderkraftwagen) Zug Anlage 3: Gliederung Panzerspähzug Polizei-Einsatzstab-Südost, 21.1.1942 269 Anlage 4: Stärke- und Ausrüstungsnachweisung Polizei-Panzerabteilung (PoLPzkw.Komp.), 1.5.1942 270 Anlage 5: Stärke- und Ausrüstungsnachweisung Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie (Pol.Pzkw.Komp.), 25.7.1942 272 Anlage 6: Stärkenachweisung Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie (t mot) (Pol.Panz.Kp.(t mot))(13.Pol.- 274 Komp.), 273.1943 Anlage 7: Stärke-und Ausrüstungsnachweisung (verstärkte) Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie (t mot) 276 ((verst) PoLPanzJComp.(t mot)), 23.1944 Anlage 8: Stärke- und Ausrüstungsnachweisung der 15. Pol.-Panzer-Komp., 11.7.1944 (mit Kriegs- 278 stärkenachweisung( Heer) Nr. 1149 Ausf. B und Kriegsstärkenachweisung (Heer) Nr. 1112 Abs. b(l.Zug) als Anhalt Anlage 9: Stärke- und Ausrüstungsnachweisung 14. (verst.) Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie 19.9.1944 280 QUELLEN- UND LITERATURVERZEICHNIS 283 ABKÜRZUNGSVERZEICHNIS 286 Seite HL DER AUSBAU DER PANZERTRUPPE DER ORDNUNGSPOLIZEI AB ENDE 1941 50 Allgemeines 50 Panzer-Spähzug beim Polizei-Einsatzstab-Südost 50 Aufstellung, Gliederung und Ausrüstung 50 Einsatz 52 Richtlinien fiir den Einsatz des Panzer-Spähzuges 52 Panzerkraftwagen-Abteilung der Schutzpolizei Wien 56 Polizei-Panzer-(Kraftwagen) Abteilung 58 Aufstellung, Gliederung und Ausrüstung 58 Einsatz 60 Unibenennung 60 1. -

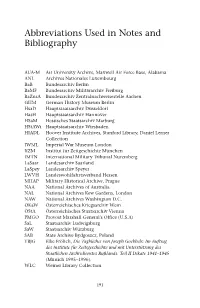

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2002 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, July 2004 Copyright © 2002 by Ian Hancock, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Michael Zimmermann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Guenter Lewy, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Mark Biondich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Denis Peschanski, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Viorel Achim, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by David M. Crowe, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................i Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich Romani Americans (“Gypsies”).......................................................................................................1 Ian -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection RG-18.002M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives Finding Aid RG-18 Latvia Updated in Feb. 2010 Finding aid to microfilm reels 1-33 RG-18.002M Acc. 1992.A.080 Title: Latvian Central State Historical Archive (Riga) records, 1941-1945. Extent: 39 microfilm reels ; 35 mm. Provenance: The Generalkommissariat in Rīga, the Reichskommissariat für das Ostland, the Latvian Legion, the Wehrmachtsbefehlhaber Ostland, and other occupation and collaboration agencies in occupied Latvia created the records during World War II. The Soviet (Red Army) captured the records at the end of the war and later deposited them in the Latvian Central State Historical Archive in Rīga, Latvia. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum received selected files from the archives in Rīga in 1992, and additional records in 2009, and 2010.. Restriction on access: No restrictions on access. Restriction on use: Restrictions on use apply. See cooperative agreement with the Central State Historical Archive, Riga. Organization and Arrangement: Arrangement is thematic. Language: German, Latvian Preferred Citation: Standard citation for United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collections Division, Archives Branch. Scope and Content: Contains information about concentration of Latvian Jews; persecution of Jews and Gypsies; confiscation of Jewish property; activities of partisans; collaboration of Latvians; activities of various police forces; and the ghettos in Riga, Liebau, and nearby localities Inventory: *Note: Reels 1-9 are catalogued in the Minaret cataloging system. Reel 1: 1. Food rations for persons in prisons and concentration camps (R30-4-5) RG-18.002M Latvian Central State Historical Archive (Riga) records, 1941-1945. -

Florian Dierl, Die Ordnungspolizei

ten gesellschaftsordnung galt. entgegen der Selbstbeschreibung als ›Hüter der Volksgemein- schaft‹ bestand die polizeiliche Praxis aus immer mehr Kontrollmaßnahmen, wenngleich diese häufig mit technokratischen Argumenten wie etwa dem erhöhten Verkehrsaufkommen, grö- ßerem Verwaltungsbedarf oder dem Schutz der Bevölkerung im Kriegsfall begründet wurden. Anders als die berüchtigte gestapo sollte die Ordnungspolizei das freundliche gesicht des nS-Staates nach außen repräsentieren. Da sich die ›Volksgemeinschaft‹ aber nur ex negativo durch den Ausschluss der ›gemeinschaftsfremden‹ herstellen ließ, war auch sie massiv in die Verfolgungsmaßnahmen des nS-regimes eingebunden. Schon in den ersten Jahren des ›Dritten reiches‹ hatten Polizisten an der Aushöhlung des rechtsstaats mitgewirkt, indem sie bereit- willig Schutzhaftbefehle ausführten oder öffentliche Übergriffe von SA und SS gegen deren selbstdefinierte gegner gewähren ließen. Auch später nahmen sie wichtige Funktionen bei der Verfolgungspolitik gegen Juden, ›Asoziale‹ oder Sinti und roma wahr, z. B. wenn sie Über- wachungsarbeiten leisteten, Kontrollen oder Verhaftungen durchführten und anschließend die Opfer an die gestapo und die Konzentrationslager überstellten. Schikanen gegen die Opfer auf den Polizeiwachen gehörten dabei ebenso zum alltäglichen Muster polizeilichen Handelns wie die Amtshilfe beim Vollzug rassistischer Bestimmungen. Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs unterstützten die Ordnungspolizisten die Fahndungs- aktionen und Verhaftungen der Sicherheitspolizei; sie stellten Personal