Explore Music 9: Singer/Songwriter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J. Cook Pomona College Recommended Citation Cook, Cameron J., "And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 138. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/138 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 And I Heard ‘Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron Cook Senior Thesis Class of 2015 Bachelor of Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree in Religious Studies Pomona College Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction, Can You Hear It? Chapter Two: Nina Simone and the Prophetic Blues Chapter Three: Post-Racial Prophet: Kanye West and the Signs of Liberation Chapter Four: Conclusion, Are You Listening? Bibliography 3 Acknowledgments “In those days it was either live with music or die with noise, and we chose rather desperately to live.” Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act There are too many people I’d like to thank and acknowledge in this section. I suppose I’ll jump right in. Thank you, Professor Darryl Smith, for being my Religious Studies guide and mentor during my time at Pomona. Your influence in my life is failed by words. Thank you, Professor John Seery, for never rebuking my theories, weird as they may be. -

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

November 2013 Master Calendar of Cultural Events & Activities

October 2014 Master Calendar of Cultural Events & Activities Cultural Services Department, City of Albuquerque Richard J. Berry, Mayor ABC Libraries Albuquerque Museum ABQ BioPark Balloon Museum Aquarium KiMo Theatre Botanic Garden Old Town Tingley Beach South Broadway Cultural Center Zoo CONTENTS Events & Activities – All Venues Pages 1-13 Exhibitions Pages 13-14 Library programs - kids, teens, tweens, etc. Page 15-16 Ongoing programs for children and families Page 16 Ongoing events at your library Pages 16-22 Venues – locations and hours Pages 22-23 EVENTS & ACTIVITIES – ALL VENUES 1 KiMo Theatre Wednesday Cinema: Taxi Driver (1978) Wednesday 7 – 9 pm “De Niro Done Right” is the theme of the new series featuring some of Robert De Niro’s most popular films. Taxi Driver features De Niro as Travis Bickle, ex-Marine and Vietnam War veteran, who drives a NYC taxi late nights and watches seedy porn films during the day. The insomniac, who has strong opinions about right and wrong, becomes obsessed with the one bright spot in his life, Betsy, who works on the campaign of a Senator. After an incident involving her, Bickle decides he needs to do whatever it takes to make the world a better place for people like Betsy. A priority is to save a 12-year-old prostitute who he believes wants to escape the control of her pimp and lover, Matthew. Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Peter Boyle, and Albert Brooks star in this powerful film that garnered numerous awards and nominations. Rated R. General Admission $5 - 7. Tickets are available at www.KiMoTickets.com. -

FARRUKO Biography Carlos Efren Reyes Rosado, Better Known As Farruko, Was Born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, on May 2, 1991

FARRUKO Biography Carlos Efren Reyes Rosado, better known as Farruko, was born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, on May 2, 1991. This singer-songwriter is considered by experts as a musical phenomenon of our times for his great musical versatility performance expertise. Farruko has consistently demonstrated his dominion over most sub-genres of urban music like Reggaeton, Rap, Hip Hop, R & B and now Trap Latino. He has also proved his adaptability, crossing over into pop, bachata, mambo and vallenato genres. Farruko has released several albums, delighting the fans production after production. In 2011, Farruko introduced us to his first solo album, “El Talento del Bloque,” which contains 13 songs written mostly by the artist himself and included collaborations with Jose Feliciano in “Su Hija Me Gusta” and Daddy Yankee in “Romper La Discoteca.” A year later, in 2012, the artist launches his second album, “TMPR *THE MOST POWERFUL ROOKIE,” which earned a nomination for Best Urban Album of the Year at the prestigious Latin Grammy 2012. In 2013, Farruko launched his third album “Imperio Nazza - Farruko Edition,” with which Farruko toured around major U.S. Hispanic markets throughout the year, earning more notoriety and helping his fans put a face to the voice that was already taking over the airwaves, websites and digital sales charts. Part of this album was his internationally popular hit song, “Besas Tan Bien,” which reached the Top 20 in Billboard’s Latin Rhythm chart and stayed there for more than 16 consecutive weeks, and 21 weeks in total. Throughout 2014, Farruko positioned himself firmly among the most successful artist of the genre. -

Fraud Risk Management: a Guide to Good Practice

Fraud risk management A guide to good practice Acknowledgements This guide is based on the fi rst edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice. The fi rst edition was prepared by a Fraud and Risk Management Working Group, which was established to look at ways of helping management accountants to be more effective in countering fraud and managing risk in their organisations. This second edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice has been updated by Helenne Doody, a specialist within CIMA Innovation and Development. Helenne specialises in Fraud Risk Management, having worked in related fi elds for the past nine years, both in the UK and other countries. Helenne also has a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Investigation through La Trobe University in Australia and a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Management through the University of Teeside in the UK. For their contributions in updating the guide to produce this second edition, CIMA would like to thank: Martin Birch FCMA, MBA Director – Finance and Information Management, Christian Aid. Roy Katzenberg Chief Financial Offi cer, RITC Syndicate Management Limited. Judy Finn Senior Lecturer, Southampton Solent University. Dr Stephen Hill E-crime and Fraud Manager, Chantrey Vellacott DFK. Richard Sharp BSc, FCMA, MBA Assistant Finance Director (Governance), Kingston Hospital NHS Trust. Allan McDonagh Managing Director, Hibis Europe Ltd. Martin Robinson and Mia Campbell on behalf of the Fraud Advisory Panel. CIMA would like also to thank those who contributed to the fi rst edition of the guide. About CIMA CIMA, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, is the only international accountancy body with a key focus on business. -

SWE PIEDMONT Vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER

SWE PIEDMONT vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER ITALY Italy is a spirited, thriving, ancient enigma that unveils, yet hides, many faces. Invading Phoenicians, Greeks, Cathaginians, as well as native Etruscans and Romans left their imprints as did the Saracens, Visigoths, Normans, Austrian and Germans who succeeded them. As one of the world's top industrial nations, Italy offers a unique marriage of past and present, tradition blended with modern technology -- as exemplified by the Banfi winery and vineyard estate in Montalcino. Italy is 760 miles long and approximately 100 miles wide (150 at its widest point), an area of 116,303 square miles -- the combined area of Georgia and Florida. It is subdivided into 20 regions, and inhabited by more than 60 million people. Italy's climate is temperate, as it is surrounded on three sides by the sea, and protected from icy northern winds by the majestic sweep of alpine ranges. Winters are fairly mild, and summers are pleasant and enjoyable. NORTHWESTERN ITALY The northwest sector of Italy includes the greater part of the arc of the Alps and Apennines, from which the land slopes toward the Po River. The area is divided into five regions: Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna. Like the topography, soil and climate, the types of wine produced in these areas vary considerably from one region to another. This part of Italy is extremely prosperous, since it includes the so-called industrial triangle, made up of the cities of Milan, Turin and Genoa, as well as the rich agricultural lands of the Po River and its tributaries. -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

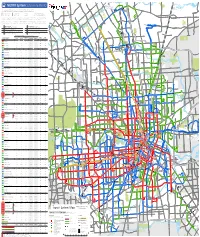

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Experiments on Patterns of Alluvial Cover and Bedrock Erosion in a Meandering Channel Roberto Fernández1, Gary Parker1,2, Colin P

Earth Surf. Dynam. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-2019-8 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Surf. Dynam. Discussion started: 27 February 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Experiments on patterns of alluvial cover and bedrock erosion in a meandering channel Roberto Fernández1, Gary Parker1,2, Colin P. Stark3 1Ven Te Chow Hydrosystems Laboratory, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at 5 Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 2Department of Geology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964, USA Correspondence to: Roberto Fernández ([email protected]) Abstract. 10 In bedrock rivers, erosion by abrasion is driven by sediment particles that strike bare bedrock while traveling downstream with the flow. If the sediment particles settle and form an alluvial cover, this mode of erosion is impeded by the protection offered by the grains themselves. Channel erosion by abrasion is therefore related to the amount and pattern of alluvial cover, which are functions of sediment load and hydraulic conditions, and which in turn are functions of channel geometry, slope and sinuosity. This study presents the results of alluvial cover experiments conducted in a meandering channel flume of high fixed 15 sinuosity. Maps of quasi-instantaneous alluvial cover were generated from time-lapse imaging of flows under a range of below- capacity bedload conditions. These maps were used to infer patterns -

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MAY 28, 2020 Page 1 of 29 INSIDE Sukhinder Singh Cassidy • ‘More Is More’: Exits StubHub Amid Why Hip-Hop Stars Have Adopted The Restructuring, Job Cuts Instant Deluxe Edition BY DAVE BROOKS • Coronavirus Tracing Apps Are Editors note: This story has been updated with new they are either part of the go-forward organization Being Tested Around information about employees who have been previously or that their role has been impacted,” a source at the the World, But furloughed, including news that some will return to the company tells Billboard. “Those who are part of the Will Concerts Get Onboard? organization on June 1. go-forward organization return on Monday, June 1.” Sukhinder Singh Cassidy is exiting StubHub, As for her exit, Singh Cassidy said that she had been • How Spotify telling Billboard she is leaving her post as president planning to step down following the Viagogo acquisi- Is Focused on after two years running the world’s largest ticket tion and conclusion of the interim regulatory period — Playlisting More resale marketplace and overseeing the sale of the even though the sale closed, the two companies must Emerging Acts During the Pandemic EBay-owned company to Viagogo for $4 billion. Jill continue to act independently until U.K. leaders give Krimmel, StubHub GM of North America, will fill the the green light to operate as a single entity. • Guy Oseary role of president on an interim basis until the merger “The company doesn’t need two CEOs at either Stepping Away From is given regulatory approval by the U.K.’s Competition combined company,” she said. -

List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor a Download Ilab’S Sweat & Toil and Comply Chain Apps Today!

2018 LIST OF GOODS PRODUCED BY CHILD LABOR OR FORCED LABOR A DOWNLOAD ILAB’S SWEAT & TOIL AND COMPLY CHAIN APPS TODAY! Browse goods Check produced with countries' child labor or efforts to forced labor eliminate child labor Sweat & Toil See what governments 1,000+ pages can do to end of research in child labor the palm of Review laws and ratifications your hand! Find child labor data Explore the key Discover elements best practice of social guidance compliance systems Comply Chain 8 8 steps to reduce 7 3 4 child labor and 6 forced labor in 5 Learn from Assess risks global supply innovative and impacts company in supply chains chains. examples ¡Ahora disponible en español! Maintenant disponible en français! B BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. ON YOUR COMPUTER All three of the USDOL flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats, at www.dol.gov/endchildlabor. These reports include the Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; the List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126; and the List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005. On our website, you can navigate to individual country pages, where you can find information on the prevalence and sectoral distribution of the worst forms of child labor in the country, specific goods produced by child labor or forced labor in the country, the legal framework on child labor, enforcement of laws related to child labor, coordination of government efforts on child labor, government policies related to child labor, social programs to address child labor, and specific suggestions for government action to address the issue.