And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

The Clique Song List 2000

The Clique Song List 2000 Now Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) American Boy (Estelle & Kanye West) Applause (Lady Gaga) Before He Cheats (Carrie Underwood) Billionaire (Travie McCoy & Bruno Mars) Birthday (Katy Perry) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (Kylie Minogue) Can’t Hold Us (Macklemore & Ryan Lewis) Clarity (Zedd) Counting Stars (OneRepublic) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Dark Horse (Katy Perry) Dance Again (Jennifer Lopez) Déjà vu (Beyoncé) Diamonds (Rihanna) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher & Pitbull) Don’t Stop The Party (The Black Eyed Peas) Don’t You Worry Child (Swedish House Mafia) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Fancy (Iggy Azalea) Feel This Moment (Pitbull & Christina Aguilera) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Find Your Love (Drake) Fireball (Pitbull) Get Lucky (Daft Punk & Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Pitbull & NeYo) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Happy (Pahrrell) Hey Brother (Avicii) Hideaway (Kiesza) Hips Don’t Lie (Shakira) I Got A Feeling (The Black Eyed Peas) I Know You Want Me (Calle Ocho) (Pitbull) I Like It (Enrique Iglesias & Pitbull) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m In Miami Trick (LMFAO) I Need Your Love (Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding) Lady (Hear Me Tonight) (Modjo) Latch (Disclosure & Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (The Black Eyed Peas) Live For The Night (Krewella) Loca (Shakira) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) More (Usher) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5 & Christina Aguliera) Naughty Girl (Beyoncé) On The Floor (Jennifer -

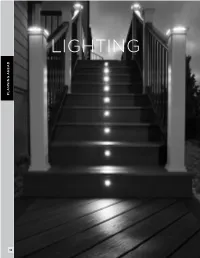

Trex Deck Lighting Installation

LIGHTING PLANNINGAHEAD 12 Trex® Outdoor Lighting™ LIGHTING & DESCRIPTION ITEM NUMBER DECK LIGHTING Pyramid or Flat Post Cap Light PYRAMID CAPS FLAT CAPS » 4" x 4" LED Post Cap Lig ht BKPYLEDCAP4X4C BKSQLEDCAP4X4C [4.55 in x 4.55 in (115 mm x 115 mm) WTPYLEDCAP4X4C WTSQLEDCAP4X4C actual internal dimensions] FPPYLEDCAP4X4C FPSQLEDCAP4X4C Use with Trex 4 in Composite Railing Posts THPYLEDCAP4X4C THSQLEDCAP4X4C » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub ® Lead VLPYLEDCAP4X4C VLSQLEDCAP4X4C GPPYLEDCAP4X4C GPSQLEDCAP4X4C LIGHTING Aluminum Post Cap Light RSPYLEDCAP4X4C RSSQLEDCAP4X4C » 2.5" x 2.5" LED Aluminum Post Cap Lig ht TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: [2.6 in x 2.6 in (66 mm x 66 mm) actual internal dimensions] BKALCAPLED25 Use with Trex 2.5 in Aluminum Railing Posts TEXTURED BRONZE: BZALCAPLED25 » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead TEXTURED WHITE: WTALCAPLED25 Deck Rail Light TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKLAMPLED C » LED Deck Rail Light TEXTURED BRONZE: BZLAMPLEDC [2.75 in (69 mm) OD] TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTLAMPLEDC » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead Wedge Deck Rail Light » LED Wedge Deck Rail Light TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKALPOSTLAMPLED [1.875 in wide x 3 in high (47 mm x 76 mm) actual dimensions] TEXTURED BRONZE: BZALPOSTLAMPLED Compatible with all Trex Railing Posts TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTALPOSTLAMPLED » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead LED Riser Lights LIGHTING TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKRISERLED4PKC » 4 LED Riser Lights TEXTURED BRONZE: BZRISERLED4PKC [1.25 in (31 mm) OD] TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTRISERLED4PKC » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub -

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

Download Our Electronic Press

“A great band. Terrific musicians. Very nice indeed” Paul Jones Rhythm & Blues, BBC radio 2, 2017 “Innovative spark, virtuoso playing & a dare-devil attitude” Pete Feenstra, Get Ready To Rock, 2017 The band’s exciting live set is based around rootsy originals; featuring strong catchy riffs, interesting arrangements & exciting grooves featuring Rob Koral's electrifying, & unmistakable touch & flow on guitar. Zoe’s dynamic & commanding vocal delivery is both eclectic & suave. The highly accomplished rhythm section of Pete Whittaker- Hammond organ (Wonderstuff) & Paul Robinson-drums (Nina Simone, Van Morrison, Paul McCartney to name a few) bring massive authority & the ability to push the music in unpredictable & exciting directions. Zoë Schwarz Blue Commotion have made a considerable impact these last five years, & is one of the bands that have added a fresh approach& vibrancy to the UK blues scene. • The band is planning an extensive 2018 tour to coincide with the release of the band's 7th album. • The band has played most of the flagship blues festivals & clubs in the UK this past 5 years. • Many magazine features, interviews & reviews. Regular plays on the BBC including the Paul Jones show. • International recognition on the blues circuit with numerous radio plays & interviews around the world. • Successful 13 day tour of Czech Republic, February 2017. • The band were runner-up best band in the British Blues Awards 2015, & Zoe was runner-up best female vocals in 2014 & 2015. Finalist in the 2017 UK Blues Challenge (close 2nd). • Best song Mary4Music (American Blues Federation) 2013. • (… other accolades include) Nomination for best electric blues album, Wasser-Prawda, Germany 2013 “A serious blues band with unique songs, tight instrumentation, & a powerful woman up front…. -

Facebook Nextdoor Twitter Digital Ads Press Enews Streaming

Setting Speed Limits: Public Input Summary, December 2019 I. Background Between May 2018 and June 2019, staff and the community actively developed the Vision Zero Action Plan. A part of the plan identified two speed-related strategies utilizing the safe systems approach that focuses on all types of road users including bicyclists, pedestrians and motorists. The safe systems approach acknowledges that people will make mistakes and seeks to design a system that allows for these mistakes, rather than expecting perfect driving behavior, to minimize death and injury. The city hosted public meetings and opened an online forum to gather public input on lowering speed limits in the city. II. Outreach Four public meetings were held on Saturday, November 16 (16 attendees), Thursday, November 21 (14 attendees), Thursday, December 11, 2019 (34 attendees) and Saturday, December 14 (41 attendees). The topic was posted online from November 16 – December 28, 2019 on Tempe Forum and received a total of 233 unduplicated survey responses. FACEBOOK NEXTDOOR TWITTER DIGITAL ADS 11/13 – public meetings 11/13 – public meetings 11/13 – public meetings 11/1-21 public meetings Reach/Impressions: 3,122 Reach/Impressions:14,915 Reach/Impressions: 3,341 Reach/Impression Engagement: 603 Engagement: 603 Engagement: 48 168,604 Engagement: 200 12/5 – public meetings 12/5 – public meetings 12/5 – public meetings Reach/Impressions: 3,269 Reach/Impressions:10,378 Reach/Impressions: 5,143 12/1-14 public meetings Engagement: 759 Engagement: 117 Engagement: 62 Reach/Impressions: 262,043 Engagement: 387 STREAMING PRESS ENEWS 12/15-28 public input Reach/Impressions: Pandora ads 10/30 – public meetings 11/14 – Tempe this Week: 60,771 Impressions: 104,851 Emails sent: 1,489 Emails sent: 3,774 Engagement: 238 Click rate: 44 open rate: 27.8% open rate: 33.8% 12/05 – public meetings 12/12 – Tempe this Week: IHeartRadio ads Impressions: 47,248 Emails sent: 1,551 Emails sent: 3,764 Click rate: 0 open rate: 30.9% open rate: 35.5% III. -

Hackensack, NJ Mar 8, 2012 – Mar 11, 2012

22001122 RReeggiioonnaall RReessuullttss Hackensack, NJ Mar 8, 2012 – Mar 11, 2012 Mr. StarQuest Alen Motoki - Bottom Of The Barrel - Dance Dimensions Petite Miss StarQuest Lauren Torres - Rockin' Robin - For Dancers Only Junior Miss StarQuest Olivia Alboher - Roxie - For Dancers Only Teen Miss StarQuest Alexa DiVirgilio - I've Got Rhythm - For Dancers Only Miss StarQuest Amanda Tarantino - Stairway To Heaven - Dance Dimensions Top Select Petite Solo 1st Place - Lauren Torres - Rockin' Robin - For Dancers Only 2nd Place - Melissa Bauer - Shake It Up - Debi's Dance 3rd Place - Ela Albardak - Hey Mickey - Dance Dimensions Top Select Junior Solo 1st Place - Olivia Alboher - Roxie - For Dancers Only 2nd Place - Jessica King - Yellow - Art Of Dance 3rd Place - Kristen Hellar - Mad World - Dance connection 4th Place - Daniella Zunic - They're Playing My Song - For Dancers Only 5th Place - Sidney Zaref - Jumbalaya - For Dancers Only 6th Place - Kristen Vasconcelos - Life Of The Party - For Dancers Only 7th Place - Brianna Hentschel - Me And My Baby - Performing Arts Academy 8th Place - Kaitlyn Lack - Come On Now - Dance Dimensions 9th Place - Samantha Torres - The Dressing Song - For Dancers Only 10th Place - Isabella Apgar - Paper Wings - MVMT Dance Center Top Select Teen Solo 1st Place - Francesca Crupi - Unchained Melody - For Dancers Only 2nd Place - Kelly O'Keefe - Until We Bleed - Art Of Dance 3rd Place - Jessica Bell - One And Only - Art Of Dance 4th Place - Haley Connington - Heavy Cross - For Dancers Only 5th Place - Paige Nagy - Lullaby -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Fraud Risk Management: a Guide to Good Practice

Fraud risk management A guide to good practice Acknowledgements This guide is based on the fi rst edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice. The fi rst edition was prepared by a Fraud and Risk Management Working Group, which was established to look at ways of helping management accountants to be more effective in countering fraud and managing risk in their organisations. This second edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice has been updated by Helenne Doody, a specialist within CIMA Innovation and Development. Helenne specialises in Fraud Risk Management, having worked in related fi elds for the past nine years, both in the UK and other countries. Helenne also has a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Investigation through La Trobe University in Australia and a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Management through the University of Teeside in the UK. For their contributions in updating the guide to produce this second edition, CIMA would like to thank: Martin Birch FCMA, MBA Director – Finance and Information Management, Christian Aid. Roy Katzenberg Chief Financial Offi cer, RITC Syndicate Management Limited. Judy Finn Senior Lecturer, Southampton Solent University. Dr Stephen Hill E-crime and Fraud Manager, Chantrey Vellacott DFK. Richard Sharp BSc, FCMA, MBA Assistant Finance Director (Governance), Kingston Hospital NHS Trust. Allan McDonagh Managing Director, Hibis Europe Ltd. Martin Robinson and Mia Campbell on behalf of the Fraud Advisory Panel. CIMA would like also to thank those who contributed to the fi rst edition of the guide. About CIMA CIMA, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, is the only international accountancy body with a key focus on business. -

Due to Overwhelming Demand Jay-Z and Eminem's Historic

DUE TO OVERWHELMING DEMAND JAY-Z AND EMINEM’S HISTORIC “HOME AND HOME” TOUR ADD ADDITIONAL SHOWS IN DETROIT AND NEW YORK TICKETS GO ON SALE FRIDAY, JUNE 25TH Tickets to EMINEM and JAY-Z’ historic “Home And Home” tour went on sale today to presale partners with overwhelming fan demand. In response to the tremendous demand, and in preparation for tomorrow’s public on-sale, another show has been added in Detroit at Comerica Park on Friday, September 3rd and in New York at Yankee Stadium on Tuesday, September 14th. This is the only time these two superstars will perform together. Tickets for all four shows, produced by Live Nation, go on sale to the public on Friday, June 25 at 10:00 am local time at LiveNation.com. JAY-Z AND EMINEM’S “HOME AND HOME” TOUR DATES INCLUDE: September 2 Detroit, MI Comerica Park September 3 Detroit, MI Comerica Park September 13 New York, NY Yankee Stadium September 14 New York, NY Yankee Stadium. The same day that tickets go on sale, EMINEM and JAY-Z take over late night television in support of the tour when they perform together on the roof of the Ed Sullivan Theater building on LATE SHOW with DAVID LETTERMAN, taped Monday, June 21 to be broadcast Friday, June 25 (11:35 PM-12:37 AM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. Since 1996, 10-time Grammy award-winner, Shawn “JAY-Z” Carter has dominated the rap industry and set trends for a generation. Through his own label, Roc Nation, JAY-Z released The Blueprint 3, his 11th number one album, putting him ahead of Elvis for the most number one albums by any solo artist.