Media Platforms 10.07.19.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Mins Rapid Growth Session

Adcore Webinars 20 mins rapid growth session Yossi Elchanan Federica Mueller CMO Partner Manager • A leading international digital marketing solutions provider since 2006 • 15 years of experience in digital advertising • Technology developers for digital marketing automation • Google, Microsoft, Facebook & TikTok premier partners • Listed on the TSXV (Toronto Stock Exchange) and the FSE (Frankfurt Stock Exchange) About Adcore 2 Agenda • 4 points for rapid growth 5:52 • Opportunity alert! 3:24 • The future is almost here: Roadmap to success 15:36 3 4 points for rapid growth 4 4 points for rapid growth 1. New Manager Account (MCC) structure Same as Google, you are now able to easily 5 Better organization of insights: Manager Account Overview The new Manager account structure is supported with a better Management dashboard 6 4 points for rapid growth 2. Easier, improved import from Google two different platforms? • Use the Import Accounts feature to import all your campaigns from Google. • Use Scheduling in order to keep them updated 7 4 points for rapid growth You can now import from Google Ads: Items that can’t be imported but can be re- created using Microsoft Advertising • 20 thousand campaigns • Account-level App Extensions • 10 million ad groups • Ad group-level App Extensions • 20 million keywords • Automated rules • 20 million ads • IP exclusions • 5.5 million ad group-level and campaign-level • Remarketing lists and associations negative keywords combined • 10 million ad group product partitions • 200,000 all other entities combined • 3 million targets 8 4 points for rapid growth 3. Let DSA do the work for you Dynamically target relevant search terms Now open for tier 1 countries Tip: Start with high bids to gain traffic at first 9 4 points for rapid growth 4. -

Yahoo! Entertainment & Lifestyle Fellowship

A little about us: Verizon Media, a subsidiary of Verizon, is a values-led company committed to building brands people love. We reach over one billion people globally with a dynamic house of 20+ media and technology brands. A global leader in digital and mobile, Verizon Media is crafting the future of media. We are an award-winning team of investigative, enterprise, trending and breaking news editors, reporters and producers with a track record of breaking stories that capture national attention. Our platforms reach hundreds of millions of users each month, so when we break news, it has the power to shape the conversation. We also have a laser focus to engage, inform and captivate our mobile audience. As a multimedia journalist, you get to make an impact and have your content resonate with readers across the globe. At Verizon Media, we provide fellows the rare opportunity to engage with over a billion monthly active users. On May 24th, 2021, we’re kicking off our Multimedia Journalism Fellowship program in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and potentially a few other major locations, including your home. The Fellowship program will run through May 20th, 2022. In order to be considered all applicants must be members in good standing. This is a paid Fellowship opportunity. The Perks: Flexible work schedule - We’ll help you work where you need to, when you need to. Because life happens. Room to grow - Learning is built into every role here. You’ll get mentorship and take ownership. Benefits - We’ve got you covered. Our benefits include comprehensive healthcare, a great 401k, and more. -

Verizon Communications Inc. 2020 Form 10-K

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark one) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number: 1-8606 Verizon Communications Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 23-2259884 (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) of incorporation or organization) 1095 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10036 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 395-1000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol(s) Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, par value $0.10 VZ New York Stock Exchange Common Stock, par value $0.10 VZ The NASDAQ Global Select Market 1.625% Notes due 2024 VZ24B New York Stock Exchange 4.073% Notes due 2024 VZ24C New York Stock Exchange 0.875% Notes due 2025 VZ25 New York Stock Exchange 3.250% Notes due 2026 VZ26 New York Stock Exchange 1.375% Notes due 2026 VZ26B New York Stock Exchange 0.875% Notes due 2027 VZ27E New York Stock Exchange 1.375% Notes due 2028 VZ28 New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2028 VZ28A New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2029 VZ29B New York Stock Exchange 1.250% Notes due 2030 VZ30 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2030 VZ30A -

Verizon Media Déclaration Infox 2019.Pdf

○ Targeted population (e.g. age, interests): No specific targeting - age limitations are included where relevant to ensure that children are not a target of the offerings. ○ Type of content displayed (e.g. video, text, images): On both products, images, text, videos. ○ Themes: ■ Yahoo Portal: mainly News, Sport, Finance, People, Style, Cinema ■ Yahoo Search: Categories/topics of content are determined by the user’s search query ○ Business model (source of revenue) ■ Yahoo Portal: Mainly Advertising. ■ Yahoo Search: Revenue share from Microsoft (search engine provider), based on search advertising. ○ Number of employees dedicated to the service globally and in France: ■ Globally: This is very difficult to determine given the nature of our business as staff are shared across functions and territories. ■ France: ○ Results in France for the Yahoo Portal and Yahoo search service in 2019 Verizon Media EMEA Limited offers the Yahoo Portal and Yahoo Search services in France. ○ Other Verizon Media (“ VZM”) online services (branded Yahoo) are offered in EMEA by Verizon Media EMEA Limited, a company incorporated in Ireland, as specified in its ‘Terms of Service’ available at https://www.verizonmedia.com/policies/ie/fr/verizonmedia/terms/otos/index.html. Yahoo Search - VZM’s exclusive web search and paid search provider is Microsoft’s Bing, which controls both the crawling of the web, indexing of such crawled web content and the search algorithm. When users submit search queries to Yahoo Search, those queries are sent to Microsoft, which returns algorithmic and sponsored results for display to users. Microsoft determines which results are returned and the order in which the results are to be displayed. -

Verizon Media DSP

Verizon Media DSP Verizon confidential and proprietary. Unauthorized disclosure, reproduction or other use prohibited. 1 Walled gardens ● Massive scale ● Exclusive supply ● Deterministic ID ● Unique data The best of both worlds DSP Independent DSPs ● Agnostic ● Transparency ● Customization Verizon confidential and proprietary. Unauthorized disclosure, reproduction or other use prohibited. DSP & native marketplace SSPs & Exchange The right stack Connections that fuel the ecosystem Video Syndication Premium content brands & partnerships Media Platform 3 Verizon confidential and proprietary. Unauthorized disclosure, reproduction or other use prohibited. Identity at the core Verizon confidential and proprietary. Unauthorized disclosure, reproduction or other use prohibited. 4 Verizon Media’s Identity Graph App Mobile 2B Devices 1M Apps Carrier Search 9B / month DOOH Email 30B / day identity graph 240M profiles Commerce $220M / day (US) Native Desktop Ad exposure 200B Device & engagement daily cross-screen ID data signals across Location Audio Verizon Media 225M MAUs IP Bid stream & platform data Content Verizon confidential and proprietary. Unauthorized disclosure, reproduction or other use prohibited. Cookies 1.2B MAUs Verizon Media Audiences Leveraging diverse and accurate data on over 1B consumers across 1M characteristics, we make it easy for you to reach the right audience at scale. Verizon Media Audiences build on the success of Lower CPC on Lift in CVR rd our previous Interest categories performance 51% mobile over 3 party 71% over 3rd party Audiences available: Use cases Interests & Household In-market Conquesting behavior & life stage audiences Performance Audiences based on insights Audiences based on signals that Seed data from purchases data from signals such as search, define life moments from via email or 3rd parties are scaled Brand Awareness purchase behavior, site visits and registered users, carrier to vertical based audiences device usage. -

Verizon up to Speed Live Friday, August 21, 2020 Redefining

Verizon Up To Speed Live Friday, August 21, 2020 Redefining Communication Access www.acscaptions.com >> Stop me if you've heard this one before, we are living through unprecedented. >> Unprecedented. >> Unprecedented. >> Unprecedented. >> Unprecedented. >> I am not sure how many times I have used the word unprecedented, but it's a really good word. >> So much of what we do now is virtual. Meetings, happy hours, graduations, even weddings. Now it's time for a virtual anniversary. Won't you join me? 20 years ago, on June 30th, Verizon was born. It was an era of pay phones, dial-up internet, and not so smart wireless phones. We have made so much history since then, it's worth a look back at some of what went into who we are today. There was our crisis response to September 11th, 2001. >> I have seen people from everywhere down here, working together, pulling together, and we are going to get this thing up and running. >> A character-defining effort with V Teamers working around the clock to get things back up in a little more than a week. There was this iconic campaign, begun in 2002. >> Can you hear me now? Can you hear me now? Can you hear me now? Good. >> Some of you are so young, you may not know this guy actually worked for us first. There was the birth of our Verizon credo in 2004. >> Who is this company that we call Verizon? >> Our historic pioneering of mass-scale fiber optics home with Fios, our recovery response to Hurricane Katrina. -

Up to Speed Live Tuesday, July 21, 2020 12 PM ET ¶¶ >> HELLO, MY

Up To Speed Live Tuesday, July 21, 2020 12 PM ET ¶¶ >> HELLO, MY NAME IS CHRISALYN. I'M AN ACCOUNT MANAGER HERE IN LAS VEGAS. I HAVE BEEN WITH VERIZON FOR 10 YEARS THIS MONTH. I WAS BORN AND RAISED IN THE PHILIPPINES, WHICH IS 40 MINUTES TO 1 HOUR FROM MANILA. I'VE ALWAYS BEEN THAT PERSON WHO IS A GO-GETTER. I TRAVELED WITH MY FLIP FLOPS, WITH ONE LUGGAGE, AND $500 IN MY POCKET. ALL I KNEW WAS I WAS GOING TO SAN FRANCISCO, I HAD A MAP, AND MY AMERICAN DREAM. AND TO NOW, IT STILL GIVES ME GOOSIES WHEN I THINK ABOUT IT. OH MY GOD, WHAT WAS I THINKING. ARRIVED THERE. IT WAS FREEZING COLD. I USED MY $500 GET ME SOME BOOTS. I WAS FREEZING. I GOT A JOB WITH VERIZON. FOR ME, ALONG THE WAY WITH THIS JOURNEY WITH VERIZON, THE JOURNEY IN THE U.S., BEING RESILIENT, AND HAVING HUMAN COMPASSION HAS HELPED ME OUT NOT ONLY IN MY LIFE, BUT ALSO IN MY VERIZON CAREER. WHERE I CAME FROM IN THE PHILIPPINES, THERE'S PLACES WHERE THEY DON'T HAVE ELECTRICITY. I AM SO THANKFUL THAT VERIZON HAS PROVIDED ME THE MEANS OF BEING ABLE TO HELP OUT. SO, LAST MONTH ALONG WITH MY HIGH SCHOOL CLASSMATES, WE WERE ABLE TO GENERATE ALMOST 300,000 PESOS SO, WE COULD BUY BASIC NEEDS, BASIC FOOD, BASIC MEDICAL SUPPLIES. HERE WEEKEND I MAKE MASKS WITH MY MOTHER. I HAVE A BUNCH ALREADY CUT. THERE'S DIFFERENT TYPES OF ONES. THIS ONE IS FOR TEACHERS. -

Analysis of the Impact of Public Tweet Sentiment on Stock Prices

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2020 A Little Birdy Told Me: Analysis of the Impact of Public Tweet Sentiment on Stock Prices Alexander Novitsky Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Business Analytics Commons, Portfolio and Security Analysis Commons, and the Technology and Innovation Commons Recommended Citation Novitsky, Alexander, "A Little Birdy Told Me: Analysis of the Impact of Public Tweet Sentiment on Stock Prices" (2020). CMC Senior Theses. 2459. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2459 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College A Little Birdy Told Me Analysis of the Impact of Public Tweet Sentiment on Stock Prices Submitted to Professor Yaron Raviv and Professor Michael Izbicki By Alexander Lisle David Novitsky For Bachelor of Arts in Economics Semester 2, 2020 May 11, 2020 Novitsky 1 Abstract The combination of the advent of the internet in 1983 with the Securities and Exchange Commission’s ruling allowing firms the use of social media for public disclosures merged to create a wealth of user data that traders could quickly capitalize on to improve their own predictive stock return models. This thesis analyzes some of the impact that this new data may have on stock return models by comparing a model that uses the Index Price and Yesterday’s Stock Return to one that includes those two factors as well as average tweet Polarity and Subjectivity. -

![Verizon up to Speed Live Monday, May 3, 2021 [MUSIC]. >> ANDY CHOI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8366/verizon-up-to-speed-live-monday-may-3-2021-music-andy-choi-1788366.webp)

Verizon up to Speed Live Monday, May 3, 2021 [MUSIC]. >> ANDY CHOI

Verizon Up To Speed Live Monday, May 3, 2021 _Redefining Communication Access www.acscaptions.com _ [MUSIC]. >> ANDY CHOI: Good afternoon thank you so much for joining us for a very special Up to Speed Live I'm here in our Basking Ridge, New Jersey headquarters. And behind me of course these men need no introductions we have Hans we have Guru let's get started we had some big news to talk about here of course so I'm going to head over to my workstation and make sure that I'm monitoring for questions our V Teamers I'm sure have questions about this morning's news. So go ahead and email us [email protected] is the email. I'll take a look at that. But once again a very special Up to Speed Live. Where we break down our big morning news this morning. And before we get to that, though, I know Hans and Guru wanted to acknowledge and talk a little bit about the news that we've been covering since last week with Christy and of course that's what's happening over in India of course our thoughts and prayers are with them so Hans with that I'll turn it over to you. >> HANS VESTBERG: Thank you Andy and hi to all of the V Teamers out there. Yes, we have some other stuff to talk about but I wanted to come a little bit what we have seen the last couple of months here and week. That COVID has not gone away. -

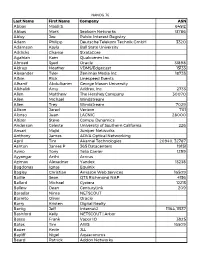

NANOG 76 Last Name First Name Company ASN Abbas Majdi S. 64512 Abbas Mark Seaborn Networks 13786 Abley Joe Public Interest Regis

NANOG 76 Last Name First Name Company ASN Abbas Majdi S. 64512 Abbas Mark Seaborn Networks 13786 Abley Joe Public Interest Registry Adam Philipp Deutsche Telekom Technik GmbH 3320 Adamson Kayla Ball State University Addicks Charise StrataCore Agahian Kam Qualcomm Inc. Ahmed Syed Oracle 31898 Aldrup Heather VDMS/Edgecast 15133 Alexander Tyler Zenimax Media Inc 18733 Alfvin Rick Linespeed Events Alhanif Abdulkarim George Mason University Alkhalidi Amy Addrex, Inc. 2733 Allen Matthew The Hershey Company 30070 Allen Michael Windstream Allen Trey Windstream 7029 Allison Jared Verizon 701 Alonso Juan LACNIC 28000 Altizer Steve Compu Dynamics Anderson Celeste University of Southern California 226 Ansari Majid Juniper Networks Anthony James ADVA Optical Networking April Tim Akamai Technologies 20940, 32787 Ashton James P 365 Datacenters 19151 Avino Tony Telia Carrier 1299 Ayyangar Arthi Arrcus Azimov Alexadner Yandex 13238 Bagdonas Ignas Equinix Bagley Christian Amazon Web Services 16509 Baillie Sean QTS Richmond NAP 4136 Ballard Michael Cyxtera 12213 Ballew Dean CenturyLink 209 Baradar Nima NETSCOUT Barreto Oliver Oracle Barry Kristen Digital Realty Bartig Jeff Internet2 11164, 11537 Bashford Kelly NETSCOUT | Arbor Basso Frank Vapor IO 3925 Bates Tim AWS 16509 Bauer Kevin JLL Bayliff Nigel Aquacomms Beard Patrick Addon Networks NANOG 76 Last Name First Name Company ASN Beatrice Tim Charter Communications 20115, 7843 Beck Jody Charter Communications 7843 Becker Sebastian Deutsche Telekom AG 3320 Beecher Tom Yahoo / Verizon Media Group 10310 American -

Word Template

U.S. Kantar Audiences for Activation Pre-defined and custom targets available on major buying platforms via LiveRamp and Eyeota. DMPs/DSPs 2019 Google | Data Store Facebook Pandora Amazon Google Ad Manager Twitter Spotify Yahoo Google Customer Snapchat LinkedIn Clear Channel Match 12 Digit Media AdKernel Appnique Clearstream 180byTWO Adlucent Appreciate Clickagy Audience Cloud - 4C Insights Admedo Column6 DDP Adobe Ad Cloud Audience Cloud - 4INFO (formerly Comcast LinkedIn TubeMogul) Adobe Audience AB Tasty Avocet Commerce Signals Manager Active Agent Adotmob BDEX comScore AcuityAds AdRoll Beeswax Connect:Select Acxiom AdSquare Bidtellect Connexity Acxiom APAC Adswizz BigaBid Conversant Acxiom Marketing AdTheorent BIGDBM Conversant Media Services (MAE) Adara AdvertServe Bombora Conversion Logic AdColony (Opera Adxcel Brandify Cox Media Mediaworks) Adcuratio Aerserv Bridge Marketing CraveLabs AdDaptive Affinio C1 Exchange CreditCards.com Intelligence Addictive Mobility Aki Technologies CafeMedia Criteo AddThis Alphonso.tv Cardlytics CriticalMix AdElement Altice / A4 / NYI CDK Cross Pixel Adelphic Amobee Celtra CrossInstall AdForge Anomaly Centro DSP Crosswise Adform Apple Chalk Digital Cxense AdGear Applift Chango Data + Math Adikteev AppNexus Civic Science DMPs/DSPs 2019, continued Data Innovators Gold Lasso Kenshoo Millennial Media Millward Brown Datavant Gravy Analytics Kiip Digital GroundTruth dataxu Kinetic Social MiQ (formerly xAd) Datonics GumGum Knorex MobileFuse DeepIntent Hooked Media Limbik mPlatform Dianomi Huddled Masses Linking -

Media Sector Review

MEDIA SECTOR REVIEW INTERNET AND DIGITAL MEDIA COMMENTARY Ad Tech – Back in the Saddle and Riding High Last quarter we noted that advertising technology (Ad Tech) stocks were the strongest performing sector over the previous 12-month period. The average stock in the Ad Tech sector at the end of INSIDE THIS ISSUE the first quarter of 2021 was up 339% over the prior year. Part of this reflected the starting point: Internet and Digital Media Commentary 1 at the end of March 2020, concerns about Covid-19 and its impact on advertising had caused the Digital Media 5 average stock in the sector to decline by 27%. The other part of the story is how well Ad Tech Advertising Tech. 6 stocks recovered from the initial advertising downturn: while 2Q 2020 revenues declined, they Marketing Tech. 7 rebounded strongly in 3Q and 4Q of 2020, and that strength has continued into the first half of Social Media 8 Esports/iGaming 9 2021. Internet & Digital Media M&A Activity 10 The strong recovery in operating results combined with the strong stock price recovery has led to Traditional Media Commentary 13 TV 16 a rebound in the Ad Tech IPO market. The first half of 2021 saw Pubmatic (PUBM), Viant (DSP), Radio 17 AppLovin (APP), DoubleVerify (DV) and Integral Ad Science (IAS) go public, while Outbrain and Traditional Media M&A Activity 18 Teads filed to go public. Meanwhile, IronSource, Taboola and Innovid all agreed to go public via a Noble Overview 19 reverse merger with a SPAC (Special Purpose Acquisition Company).