The Culture of Democratic Spain and the Issue of Torture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Módulo Extra - Espanhol Com Música!

MÓDULO EXTRA - ESPANHOL COM MÚSICA! SHAKIRA - CHANTAJE (INCOMPLETA) Cuando estás _____ te alejas de ____ Te sientes sola y _________ estoy ahí Es ____ guerra de toma y dame Pues dame de eso que tienes _____ Oye baby, no seas ________ No _____ dejes con las ganas Se escucha en la _________ Que ____ no me quieres Ven y _________ en la cara Pregúntale a quien _____ quieras Vida, te juro que _____ no es así Yo nunca _______ una mala intención Yo nunca _______ burlarme de ti __________ ves, nunca se sabe Un día digo que no y _______ que sí Yo ______ masoquista Con mi cuerpo, _____ egoísta Tú ______ puro, puro chantaje Puro, puro chantaje Siempre es a ____ manera Copyright © Espanhol de Verdade - Todos os Direitos Reservados. Distribuição e reprodução sem autorização do autor são proibidos por lei. MÓDULO EXTRA - ESPANHOL COM MÚSICA! Yo te quiero _________ no quiera Tú eres puro, puro chantaje Puro, puro chantaje Vas libre como ____ aire No soy de ti ni de ________ Como tú me tientas _________ tú te mueves Esos movimientos sexies siempre me ____________ Sabes ____________ bien con tus caderas No sé _________ me tienes en lista de espera Te ________ por ahí que _____ haciendo y deshaciendo Que ________ cada noche, que te tengo ahí sufriendo Que en esta __________ soy yo la que manda No pares bola a toda esa mala _____________ Pa-pa'qué te digo na', te comen el oído No vaya’ a enderezar lo que no se _____ torcido Y como un _______ sigo trás de ti Muriendo por ____ Dime que hay pa'mi, bebé ¿______? Pregúntale ___ quien tú quieras Vida, te ________ que eso no es así Copyright © Espanhol de Verdade - Todos os Direitos Reservados. -

Stuart Christie Obituary | Politics | the Guardian

8/29/2020 Stuart Christie obituary | Politics | The Guardian Stuart Christie obituary Anarchist who was jailed in Spain for an attempt to assassinate Franco and later acquitted of being a member of the Angry Brigade Duncan Campbell Mon 17 Aug 2020 10.40 BST In 1964 a dashing, long-haired 18-year-old British anarchist, Stuart Christie, faced the possibility of the death penalty in Madrid for his role in a plot to assassinate General Franco, the Spanish dictator. A man of great charm, warmth and wit, Christie, who has died of cancer aged 74, got away with a 20-year prison sentence and was eventually released after less than four years, only to find himself in prison several years later in Britain after being accused of being a member of the Angry Brigade, a group responsible for a series of explosions in London in the early 1970s. On that occasion he was acquitted, and afterwards he went on to become a leading writer and publisher of anarchist literature, as well as the author of a highly entertaining memoir, Granny Made Me an Anarchist. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/aug/17/stuart-christie-obituary 1/5 8/29/2020 Stuart Christie obituary | Politics | The Guardian Christie’s Franco-related mission was to deliver explosives to Madrid for an attempt to blow up the Spanish leader while he attended a football match at the city’s Bernabéu stadium. Telling his family that he was going grape-picking in France, he went first to Paris, where it turned out that the only French he knew, to the amusement of his anarchist hosts, was “Zut, alors!” There he was given explosives and furnished with instructions on how to make himself known to his contact by wearing a bandage on his hand. -

Meghan Trainor

Top 40 Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) All Of Me (Dance Remix) (John Legend) Am I Wrong (Nico & Vinz) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Break Free (Ariana Grande) Cake By The Ocean (DNCE) Can’t Feel My Face (The Weeknd) Cheerleader (OMI) Clarity (Zedd) Club Can’t Handle Me (Flo Rida) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Crazy In Love (Beyonce) Delirious (Steve Aoki) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Feel This Moment (Christina Aguilera, Pitbull) Fireball (Pitbull) Forget You (Cee Lo) Get Lucky (Daft Punk, Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Ne-Yo, Pitbull) Good Feeling (Flo Rida) Happy (Pharrell Williams) Hella Good (No Doubt) Hotline Bling (Drake) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m Not The Only One (Sam Smith) Ignition Remix (R.Kelly) In Da Club (50 Cent) Jealous (Nick Jonas) Just The Way You Are (Bruno Mars) Latch (Disclosure, Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (Black Eyed Peas) Let’s Go (Calvin Harris, Ne-Yo) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) Miss Independent (Kelly Clarkson) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5, Christina Aguilera) P.I.M.P. (50 Cent) Party Rock Anthem (LMFAO) Play Hard (David Guetta, Ne-Yo, Akon) Raise Your Glass (Pink) Rather Be (Clean Bandit, Jess Glynne) Royals (Lorde) Safe & Sound (Capital Cities) Shake It Off (Taylor Swift) Shut Up And Dance (Walk the Moon) Sorry (Justin Bieber) Starships (Nicki Minaj) Stay With Me (Sam Smith) Sugar (Maroon 5) Suit & Tie (Justin Timberlake) Summer (Calvin Harris) Talk Dirty (Jason DeRulo) Timber (Kesha & Pitbull) Titanium (David Guetta, -

Shakira Announces El Dorado World Tour, Presented By

For Immediate Release SHAKIRA ANNOUNCES EL DORADO WORLD TOUR, PRESENTED BY RAKUTEN The World Tour Includes Stops Throughout Europe and North America with Latin American Dates Forthcoming Tickets On-Sale Friday, June 30th; Citi Presale Begins Tuesday, June 27th; Viber Presale Begins Wednesday, June 28th; Live Nation Presale Begins Thursday, June 29th 11th Studio Album “EL DORADO” Certified 5x Platinum Los Angeles, CA (June 27, 2017) – Twelve-time GRAMMY® Award-winner and international superstar Shakira has announced plans to embark on her EL DORADO WORLD TOUR, presented by Rakuten. The tour, produced by Live Nation, will feature many of her catalog hits and kicks off on November 8th in Cologne, Germany. It will feature stops throughout Europe and the US including Paris’ AccorHotels Arena and New York’s Madison Square Garden. A Latin American leg of the tour will be announced at a later date. “Thank you all so much for listening to my music in so many places around the world. I can’t wait to be onstage again singing along with all of you, all of your favorites and mine. It's going to be fun! The road to El Dorado starts now!” Shakira said. The tour announcement comes on the heels of Shakira’s 11th studio album release, EL DORADO, which hit #1 on iTunes in 37 countries and held 5 of the top 10 spots on the iTunes Latino Chart within hours of its release. The 5x platinum album, including her already massive global hits - “La Bicicleta,” “Chantaje,” “Me Enamoré,” and “Déjà vu”- currently holds the top spot on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums, marking her 6th #1 album on this chart. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Shakira HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH FIGURE PRESENTATION by CORA WILSON the Education and Early Childhood of Shakira

Shakira HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH FIGURE PRESENTATION BY CORA WILSON The Education and Early Childhood of Shakira Shakira’s full name is Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll. She was born on February 2nd, 1977 in Barranquilla, Colombia. Shakira knew the alphabet when she was only 18 months old. She started school at 4 years old. Shakira grew up in a poor family with her older brother and sisters from her dad’s previous marriage. At age 11 she started learning guitar. At age 13 she moved to Bogota in hopes of pursuing modelling, but got a singing career instead. SHAKIRA HAS WON 2 GRAMMY AWARDS. SHE HAS ALSO BEEN NOMINATED FOR A GOLDEN GLOBE. ONE OF SHAKIRA’S EARLIER ALBUMS WAS #1 ON BILLBOARD’S LATIN ALBUM CHART FOR 11 WEEKS. THAT ALBUM ALSO PRODUCED 2 U.S. #1 HITS. Shakira’s Notable IN JUNE OF 2006, SHAKIRA’S SONG “HIPS DON’T LIE” MADE THE BILLBOARD Achievements HOT 100. and Awards SHAKIRA SIGNED A TEN YEAR CONTRACT WITH LIVE NATION IN 2008. Shakira’s Career Highlights and Accomplishments After 2000, Shakira started taking Shakira has been belly English lessons. Shakira and her boyfriend dancing since she was 4. Gerard Pique, a soccer player The following year, her debut for Barcelona, welcomed son Her name means “woman of Laundry Service entered the Milan in January 2013. grace” in Arabic. charts at No. 3. The following months, Shakira She released her first Spanish- made her debut as a judge on language album as a the voice. teenager. SHAKIRA’S MOTHER’S NAME IS NIDIA DEL CARMEN RIPOLL, AND IS A NATIVE COLUMBIAN. -

La Bicicleta by Carlos Vives Feat Shakira Easy Piano Sheet Music

La Bicicleta By Carlos Vives Feat Shakira Easy Piano Sheet Music Download la bicicleta by carlos vives feat shakira easy piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 3 pages partial preview of la bicicleta by carlos vives feat shakira easy piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 6018 times and last read at 2021-09-27 11:45:20. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of la bicicleta by carlos vives feat shakira easy piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Easy Piano, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music La Bicicleta By Carlos Vives Feat Shakira Piano La Bicicleta By Carlos Vives Feat Shakira Piano sheet music has been read 8339 times. La bicicleta by carlos vives feat shakira piano arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 12:37:40. [ Read More ] Chantaje A Minor By Shakira Easy Piano Chantaje A Minor By Shakira Easy Piano sheet music has been read 6491 times. Chantaje a minor by shakira easy piano arrangement is for Beginning level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 02:45:33. [ Read More ] Waka Waka This Time For Africa C Major By Shakira Easy Piano Waka Waka This Time For Africa C Major By Shakira Easy Piano sheet music has been read 4401 times. Waka waka this time for africa c major by shakira easy piano arrangement is for Beginning level. -

La Bicicleta

La bicicleta Ella es la favorita la que canta en la zona Carlos Vives Ft Shakira (2016) se mueven sus cadera como un barco en las olas tiene los pies descalzo como un niño que adora Nada voy hacer y su cabello es largo, son un sol que te antoja rebuscando en las heridas del pasado no voy a perder Le gusta que el digan que es la niña, la lola yo no quiero ser un tipo de otro lado le gusta que la miren cuando ella baila sola le gusta más la casa, que no pasen las horas A tu manera, es complicado le gusta Barranquilla1, le gusta Barcelona en una bici que te lleve a todos lados un vallenato desesperado Lleva, llévame en tu bicicleta una cartica que yo guardo óyeme Carlos llévame en tu bicicleta quiero que recorramos juntos esta zona Estribillo : desde Santa Marta hasta La Arenosa2 En donde te escribí Lleva, llévame en tu bicicleta para que juguemos bola de trapo3 allá en chancletas4 que …................................. y que …...................................... tanto que si a Pique algún día le muestras El Tayrona5 que hace rato está …........................................ después no querrá irse para Barcelona ............................................., …....................................... A mi manera, descomplicado en una bici que te lleva a todos lados La que yo guardo en donde te escribí un vallenato, desesperado que te sueño y que te quiero tanto una cartica que yo guardo que hace rato está mi corazón latiendo por ti, latiendo por ti Estribillo Puedo …......................................... Lleva, llévame en tu bicicleta caminando relajada entre la gente óyeme carlos llévame en tu bicicleta …............................................ -

18LG Nominees English

Nominee_Export Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, Inc. List of Nominees for the 18th Annual Latin GRAMMY Awards Nominee Name Category #s Combined Category Names Ainhoa Ábaunz 41 Best Latin Children’s Album Alejandro Abeijón 4 Best New Artist Adam Abeshouse 42 Best Classical Album Julie Acosta 22 Best Ranchero/Mariachi Album Antonio Adolfo 31 Best Latin Jazz/Jazz Album Camilla Agerskov 47 Best Short Form Music Video Gilberto Aguado 48 Best Long Form Music Video Gustavo Aguado 17, 48 Best Contemporary Tropical Album, Best Long Form Music Video Leonardo Aguilar 25 Best Norteño Album Yuvisney Aguilar 28 Best Folk Album Yuvisney Aguilar & Afrocuban Jazz Quartet 28 Best Folk Album Cheche Alara 2 Album Of The Year Rubén Albarrán 13 Best Alternative Music Album Albita 18 Best Traditional Tropical Album Daniel Alvarez 10 Best Rock Album Diego Álvarez 48 Best Long Form Music Video Hildemaro Álvarez 42 Best Classical Album J Álvarez 8 Best Urban Music Album Oscar Álvarez 23 Best Banda Album Andrea Amador 11 Best Pop/Rock Album Vicente Amigo 30 Best Flamenco Album AnaVitória 34 Best Portuguese Language Contemporary Pop Album Julio Andrade 35 Best Portuguese Language Rock or Alternative Album Marc Anthony 41 Best Latin Children’s Album Page 1 Nominee_Export Gustavo Antuña 13 Best Alternative Music Album Eunice Aparicio 22 Best Ranchero/Mariachi Album The Arcade 2 Album Of The Year Rafael Arcaute 1, 2, 9, 14 Record Of The Year, Album Of The Year, Best Urban Song, Best Alternative Song Paula Arenas 4 Best New Artist Ricardo Arjona 3 Song Of -

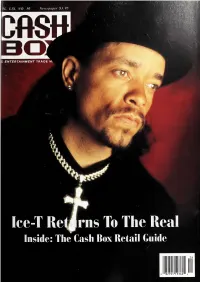

Ice-T Re^Rns to the Real Inside: the Cash Box Retail Guide

'f)L. LIX, NO. 30 Newspaper $3.95 ftSo E ENTERTAINMENT TRADE M. rj V;K Ice-T Re^rns To The Real Inside: The Cash Box Retail Guide 0 82791 19360 4 VOL. LIX, NO. 30 April 6, 1996 NUMBER ONES STAFF GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher POP SINGLE KEITH ALBERT THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Exec. V.PJOeneral Manager Always Baby Be My M.R. MARTINEZ Mariah Carey Managing Editor (Columbia) EDITORIAL Los Angdes JOhM GOFF GIL ROBERTSON IV DAINA DARZIN URBAN SINGLE HECTOR RESENDEZ, Latin Edtor Cover Story Nashville Down Low ^AENDY NEWCOMER New York R. Kelly Ice-T Keeps It Real J.S GAER (Jive) CHART RESEARCH He’s established himself as a rapper to be reckoned with, and has encountered Los Angdes BRIAN PARMELLY his share of controversy along the way. But Ice-T doesn’t mind keepin’ it real, ZIV RAP SINGLE which is the key element in his new Rhyme Syndicate/ Priority release Ice VI: TONY RUIZ PETER FIRESTONE The Return Of The Real. The album is being launched into the consciousness of Woo-Hah! Got You... Retail Gude Research fans and foes with a wickedly vigorous marketing and media campaign that LAURI Busta Rhymes Nashville artist’s power. Angeles-based rapper talks with underscores the The Los Cash GAIL FRANCESCHl (Elektra) Box urban editor Gil Robertson IV about the record, his view of the industry MARKETINO/ADVERTISINO today and his varied creative ventures. Los A^gdes FRANK HIGGINBOTHAM —see page 5 JOI-TJ RHYS COUNTRY SINGLE BOB CASSELL Nashville To Be Loved By You The Cash Box Retail Guide Inside! TED RANDALL V\^nonna New York NOEL ALBERT (Curb) CIRCULATION NINATREGUB, Managa- Check Out Cash Box on The Internet at JANET YU PRODUCTION POP ALBUM HTTP: //CASHBOX.COM. -

17LG Nominees ENGLISH

Nominee_Export Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, Inc. List of Nominees for the 17th Annual Latin GRAMMY Awards Nominee Name Category #s Combined Category Names A Corte Musical 42 Best Classical Album Enrique Abdón Collazo 18 Best Traditional Tropical Album Sophia Abrahão 4 Best New Artist Raúl Acea Rivera 18 Best Traditional Tropical Album Dani Acedo 47 Best Short Form Music Video Héctor Acosta "El Torito" 17 Best Contemporary Tropical Album Dario Adames 11 Best Pop/Rock Album Mario Adnet 31 Best Latin Jazz Album Antonio Adolfo 31 Best Latin Jazz Album Adrián 6 Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album Raul Agraz 31 Best Latin Jazz Album Gustavo Aguado 17 Best Contemporary Tropical Album Lino Agualimpia Murillo 19 Best Tropical Fusion Album Pepe Aguilar 1 Record Of The Year José Aguirre 15 Best Salsa Album Lisa Akerman Stefaneli 44 Best Recording Package Bori Alarcón 2 Album Of The Year Pablo Alborán 1, 2, 5 Record Of The Year, Album Of The Year, Best Contemporary Pop Vocal Album Rolando Alejandro 2 Album Of The Year Álvaro Alencar 2 Album Of The Year Alexis 7 Best Urban Fusion/Performance Alexis y Fido 7 Best Urban Fusion/Performance Omar Alfanno 20 Best Tropical Song Sergio Alvarado 47 Best Short Form Music Video Page 1 Nominee_Export Andrea Álvarez 10 Best Rock Album Diego Álvarez 48 Best Long Form Music Video Julión Álvarez 23 Best Banda Album Laryssa Alves 39 Best Brazilian Roots Album Lizete Alves 39 Best Brazilian Roots Album Lucy Alves & Clã Brasil 39 Best Brazilian Roots Album Lucy Alves 39 Best Brazilian Roots Album Jorge Amaro 11 Best Pop/Rock Album Remedios Amaya 30 Best Flamenco Album Elvis "Magno" Angulo 15 Best Salsa Album Juan Alonzo V. -

La Cárcel De Carabanchel. Lugar De Memoria Y Memorias Del Lugar

Menú principal Índice de Scripta Nova Scripta Nova REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA DE GEOGRAFÍA Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES Universidad de Barcelona. ISSN: 1138-9788. Depósito Legal: B. 21.741-98 Vol. XVIII, núm. 493 (02), 1 de noviembre de 2014 [Nueva serie de Geo Crítica. Cuadernos Críticos de Geografía Humana] LA CÁRCEL DE CARABANCHEL. LUGAR DE MEMORIA Y MEMORIAS DEL LUGAR Carmen Ortiz García y Mario Martínez Zauner CSIC. Madrid La cárcel de Carabanchel. Lugar de memoria y memorias del lugar (Resumen) En el texto se presenta una reflexión sobre la importancia patrimonial de ciertos lugares históricos ligados a funciones represivas. Se aborda el análisis del complejo penitenciario de Carabanchel y su importancia para la memoria individual y colectiva de nuestro pasado más reciente. En los numerosos ámbitos en que el pasado reciente se está poniendo en cuestión en las últimas décadas en España, uno de los más evidentes es el que afecta a las importantes huellas materiales dejadas por la guerra de 1936 y la dictadura del general Franco en el paisaje natural y en la construcción urbana y monumental del territorio. El estudio se ha llevado a cabo con una perspectiva transdisciplinaria, utilizando fuentes de información tanto históricas como etnográficas y con datos obtenidos a partir de la observación participante y el diálogo con miembros de movimientos de resistencia, expresos políticos y otros actores sociales. Palabras clave: espacios represivos, franquismo, presos políticos, subjetividad. Carabanchel Prison. Place of Memory and Memories of the Place (Abstract) This text present a reflection on the heritage significance of certain historical sites linked to repressive functions.